Vasomotor symptoms (VMS) such as hot flashes and sweats are among the most common menopausal symptoms. Menopausal hormone therapy (MHT) is the most effective therapy. The decision for or against MHT is based, among other things, on the intensity of individual symptoms, comorbidities, individual risk for certain diseases, and personal attitudes toward menopause and therapy for menopause-related symptoms. In 2015, the SGGG recommendations on MHT were updated.

Hot flashes and sweats (vasomotor symptoms, VMS) are among the most common complaints during menopause. The prevalence of these complaints is up to 50% in the reproductive phase and perimenopause and up to 80% in postmenopause. The median total duration of frequent VMS (i.e., ≥6 days with VMS in the past two weeks) is 7.4 years, and more than 11.8 years if onset occurs in premenopause or early perimenopause [1]. VMS are attributed to hypothalamic thermoregulatory dysfunction resulting from menopause-associated estrogen deficiency-induced reduction in endogenous central opioid activity [2].

Diagnostics

Basic diagnostics for VMS include history and laboratory:

- Medical history: Is the woman menopausal? (secondary amenorrhea for twelve months); questionnaire regarding menopausal symptoms e.g. Menopause Rating Scale (MRS) II

- Laboratory: Is there hypergonadotropic hypogonadism? (FSH >40 IU/l when measured three times a few weeks apart; estrogen deficiency at E2 <30 pg/ml).

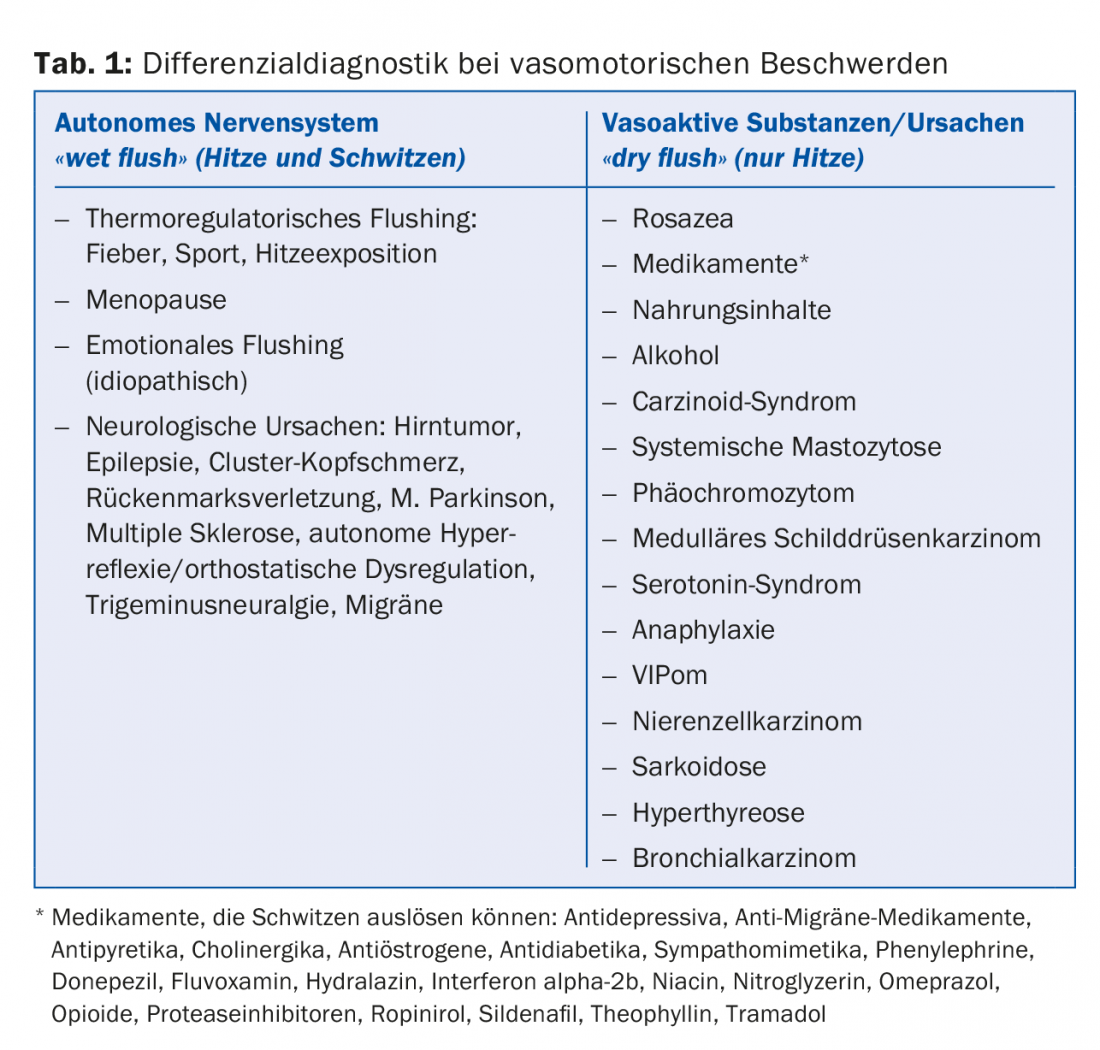

In the differential diagnosis of VMS, a distinction is made between “wet flushes” and “dry flushes,” that is, whether the sensation of heat is also accompanied by sweating (Table 1) [3,4]. Accordingly, the differential diagnosis includes:

- Laboratory diagnostics in the serum resp. EDTA blood: FSH, estradiol, progesterone, TSH, fT3, fT4, anti-TPO, TRAK, differential blood count, transaminases, crea-

- tinin, potassium, fasting blood glucose, blood cultures if necessary, HIV test, TINE test, tryptase, VIP (vasoactive intestinal peptide), calcitonin

- Laboratory diagnostics in 24-hour collected urine: 5-Hy-.

- droxyindoleacetic acid (5-HIAA), catecholamines (epinephrine, norepinephrine) or catecholamine metabolites (metanephrines, normetanephrine), methylhistamine, or 1,4-methylimidazoleacetic acid.

- Imaging if necessary: chest X-ray, CT chest, renal ultrasonography.

- Bone marrow biopsy if necessary.

Therapy

Conventional menopausal hormone therapy (MHT), alternative and complementary medicine, and non-hormonal pharmacotherapy are available for the treatment of VMS. In the following, MHT will be discussed in more detail, as in 2015 the expert letter on MHT was updated by the Swiss Society of Gynecology and Obstetrics (SGGG) [5].

Menopausal hormone therapy (MHT)

Indication, dosage and form of application: Conventional MHT is the use of estrogens, progestogens and, to a limited extent, androgens. Indications for systemic MHT include VMS. Other symptoms associated with menopause can also be improved or resolved, such as sleep disturbances, depressive moods, decreased performance and memory, bone and joint symptoms, vision, skin and mucous membrane changes, and hair loss.

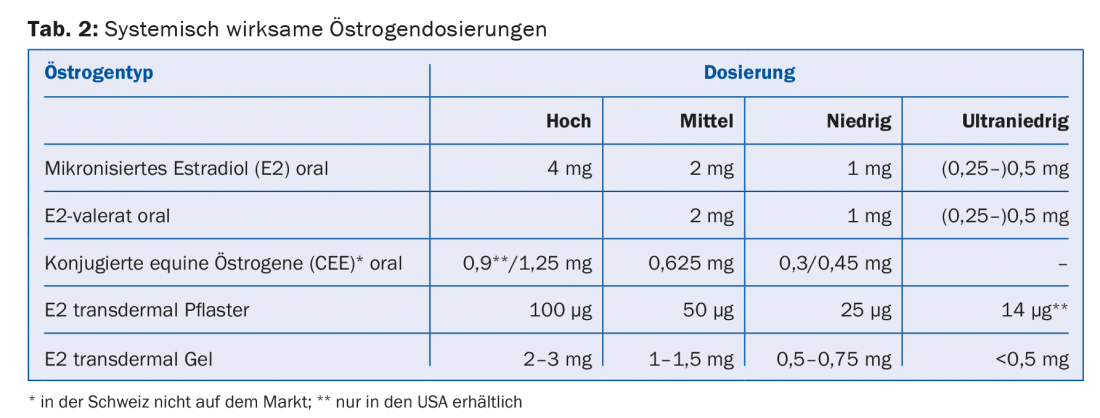

Systemically active estrogens are available in different dosages (high, medium, low and ultra-low) and forms of application ( tablet, gel, patch) (tab. 2). In women with uterus, the additional administration of a progestogen for endometrial protection is indicated. Alternatively, direct delivery of a progestogen by means of an IUD (Mirena®) is available. Both estrogen and progestin doses should be chosen as low as possible. However, for premature menopause (<40 years of age) and early menopause (<45 years of age), “true” hormone replacement should be continued until at least 51 years of age. Each MHT should be reevaluated annually. It is not necessary or reasonable to arbitrarily limit the duration of application of MHT.

Contraindications: Absolute contraindications to MHT are pregnancy, unexplained vaginal bleeding, mammary and endometrial carcinoma, and arterial and venous thromboembolism. Relative contraindications include acute liver disease, chronic severe liver dysfunction, gallstones, certain lipid metabolism disorders, hypertension, and migraine.

Additional benefits of MHT

Fracture prevention: Under MHT, osteoporosis-related fracture risk at all sites decreases significantly by 25-40%. In women at increased risk of fracture, MHT is therefore a first-line therapy even in asymptomatic cases. Fracture data are lacking for low- and ultralow-dose MHT preparations. Starting MHT for the sole purpose of preventing fractures after age 60 is not recommended. In contrast, individualized MHT alone for fracture prevention can be continued beyond age 60, provided that the potential long-term benefits and risks are considered in comparison with alternative nonhormonal therapies. Specific treatment is indicated for manifest osteoporosis (with fracture).

Coronary heart disease (CHD): intermediate-dose estrogen monotherapy significantly reduces the risk of CHD and all-cause mortality in women who start MHT at age <60 years or within 10 years of menopause (“favorable window”). Combined estrogen-progestin administration with onset within the favorable window shows a neutral to positive effect depending on the progestin used. Primary cardiovascular prevention alone is not an indication for MHT. MHT for secondary prevention and in the presence of symptomatic CHD is contraindicated.

Risks of MHT

Cerebrovascular events (CVI): The additional risk of ischemic stroke attributable to MHT increases in an age-dependent manner under oral MHT. There is no such thing as a “cheap window.” The absolute risk remains low in women <60 years in the Women’s Health Initiative (WHI) [6] and in large observational studies, with one to two cases per 10,000 woman-years. After age 60, CVI risk may reach significance under oral MHT. Under low-to-moderate dose transdermal MHT, the risk is lower. Thus, transdermal estrogen should be preferred in women with higher baseline CVI risk.

Venous thromboembolism (VTE): there is no “favorable window.” Under MHT, in the 50-59-year-old group, the incremental risk of VTE with CEE plus medroxyprogesterone acetate (MPA) is 11 and with CEE alone is four cases per 10,000 woman-years (WHI). The highest risk is found in the first months after the start of therapy. Under low-to-moderate-dose transdermal MHT, the risk is lower or not increased. Duration of use and type/dosage of progestin may influence VTE risk in combination with estrogens. Under micronized progesterone and dydrogesterone, the risk appears to be lower than under synthetic progestins.

Central nervous system: the long-term consequences of MHT started in peri- or early postmenopause for cognition and dementia are still largely unknown. MHT started late (>65 years of age) could have unfavorable effects on cognition. MHT started around menopause and continued for up to ten years may be associated with a reduced risk of AD.

Breast carcinoma: With regard to the risk of breast carcinoma, estrogen monotherapy must be distinguished from estrogen-progestin therapy. According to the WHI study, breast cancer risk and mortality are not significantly reduced in hysterectomized women on seven years of therapy with CEE alone. In the WHI, Danish Osteoporosis Prevention Study (DOPS) [7], and Nurses’ Health Study (NHS) [8] trials, estrogen monotherapy consistently showed no increase in risk for breast cancer incidence and mortality up to a cumulative observation period of 13, 16, and 19 years, respectively. With estrogen monotherapy ≥20 years, an increased risk of breast cancer was observed in normal-weight but not overweight or obese women.

The situation is different with estrogen-progestin therapy. Under CEE + MPA, the risk of breast cancer is not increased in first-time users during the first 5.6 years of treatment. After that, the risk starts to increase. Under CEE + MPA, nine more cases per 10,000 woman-years of invasive breast cancer were observed in the WHI than in the control group after a cumulative observation period of 13 years. In contrast, E2 + norethisterone acetate (NETA) in DOPS did not increase the risk of breast carcinoma within the 16-year observation period. Micronized progesterone and dydrogesterone in combination with an estrogen may be associated with lower risk than synthetic progestins. The extent of the risk increase under combined estrogen-progestin therapy thus depends on the type of progestin used and the duration of application.

Mortality

Meta-analyses, randomized-controlled trials, and observational studies all demonstrate a reduction in all-cause mortality when study participants received intermediate-dose estrogen monotherapy before age 60 or within the first 10 postmenopausal years (“favorable window”). In DOPS, all-cause mortality did not decrease significantly under E2 or under E2 + NETA. Conversely, consistent with other studies, NHS shows that prophylactic bilateral ovariectomy is associated with increased long-term mortality in women younger than 50 years. Under estrogen monotherapy, cardiac mortality and breast carcinoma mortality were significantly decreased after 13 years (WHI) and 16 years (DOPS) of observation, respectively, in addition to all-cause mortality.

Influence on other risks

In the WHI, as in the BCDDP trial, a significant reduction in colon cancer was found with oral combined CEE/MPA administration, but not with oral CEE monotherapy. Transdermal MHT does not appear to reduce the incidence of colon cancer. There is no epidemiologic evidence for a change in bronchial or gallbladder cancer risk with MHT. In contrast, oral (but not transdermal) MHT increases the risk of cholelithiasis and cholecystectomy.

Literature:

- Avis NE, et al: Duration of menopausal vasomotor symptoms over the menopause transition. JAMA Intern Med 2015; 175(4): 531-539.

- Freedman RR: Hot flashes: behavioral treatments, mechanisms, and relation to sleep. Am J Med 2005; 118 Suppl 12B: 124-130.

- von Wolff M, Stute P: Gynecological Endocrinology and Reproductive Medicine: The Practice Book. 1 ed. Schattauer GmbH, Stuttgart 2013.

- Fazio SB: Approach to flushing in adults. Uptodate 2015.

- Birkhäuser M, et al: Current recommendations on menopausal hormone therapy (MHT). Expert Letter No 42. Swiss Society of Gynecology and Obstetrics 2015.

- Manson JE, et al: Menopausal hormone therapy and health outcomes during the intervention and extended poststopping phases of the Women’s Health Initiative randomized trials. JAMA 2013; 310(13): 1353-1368.

- Schierbeck LL, et al: Effect of hormone replacement therapy on cardiovascular events in recently postmenopausal women: randomised trial. BMJ 2012; 345: e6409.

- Chen WY, et al: Unopposed estrogen therapy and the risk of invasive breast cancer. Arch Intern Med 2006; 166(9): 1027-1032.

GP PRACTICE 2016, 11(2): 14-17