Warning symptoms that must be queried include visual acuity reduction, acute bulbar pain, and acute photophobia. In case of trauma, suspected corneal involvement, acute visual loss/photophobia and acute bulbar pain, immediate emergency ophthalmologic evaluation is necessary. When using ophthalmic drugs, it is important to carefully weigh the benefits against the risks of side effects.

Approximately 2-3% of primary care and general emergency consultations involve the eyes or periocular structures [1]. A high proportion of these can be medically managed by the internist or general practitioner. However, a certain proportion requires ophthalmologic co-assessment. The aim of this article is, on the one hand, to point out the most important differential diagnoses of red eye and, on the other hand, to raise awareness of ophthalmologic emergencies.

Medical history

Already in the anamnesis important clues to the etiology of the red eye arise. If the symptoms are acute but have occurred without trauma, inflammatory (infectious or noninfectious) must be considered in the first instance. In addition, carotid sinus-cavernosus fistula and acute glaucoma must always be considered as differential diagnoses.

The pain history can provide further clues. Thus, in connection with a red eye, a pressure pain, possibly accompanied by (mostly unilateral) headache, is indicated, especially in pressure deprivation (acute glaucoma). However, pressure pain may also be indicated in carotid sinus cavernosus fistula or in inflammatory conditions by which pressure is exerted on the ocular bulb, for example, lid phlegmon or exacerbated endocrine orbitopathy.

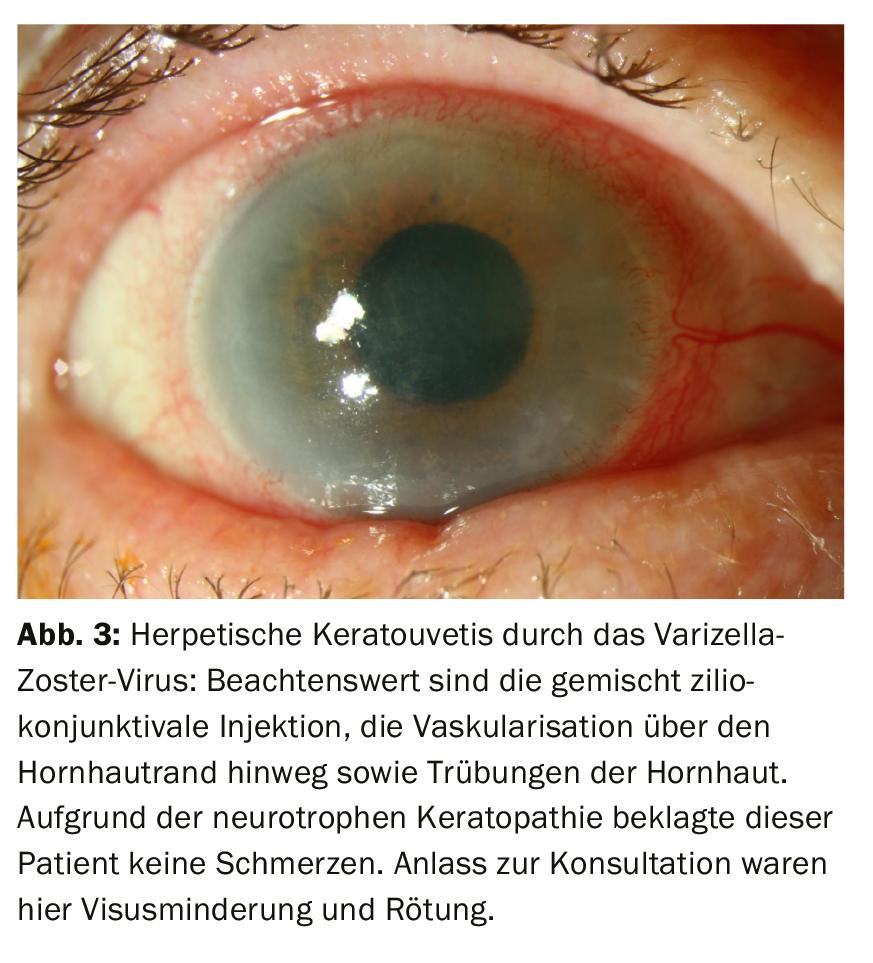

Conjunctivitis, on the other hand, tends to cause burning and itching as well as increased lacrimation (epiphora) . Sharp pain and photophobia are often described in corneal involvement. Red eye without pain must be thought of as having a neurotrophic component, such as the herpetic viral inflammations or the rare but serious scleromalacia perforans (a form of scleritis). In dry eye (keratoconjunctivitis sicca), typically long-standing burning eyes increasing over the course of the day are reported, sometimes also itching and heaviness of the eyes, tired eyes or foreign body sensation. A reduction in visual acuity must always be interpreted as a warning sign.

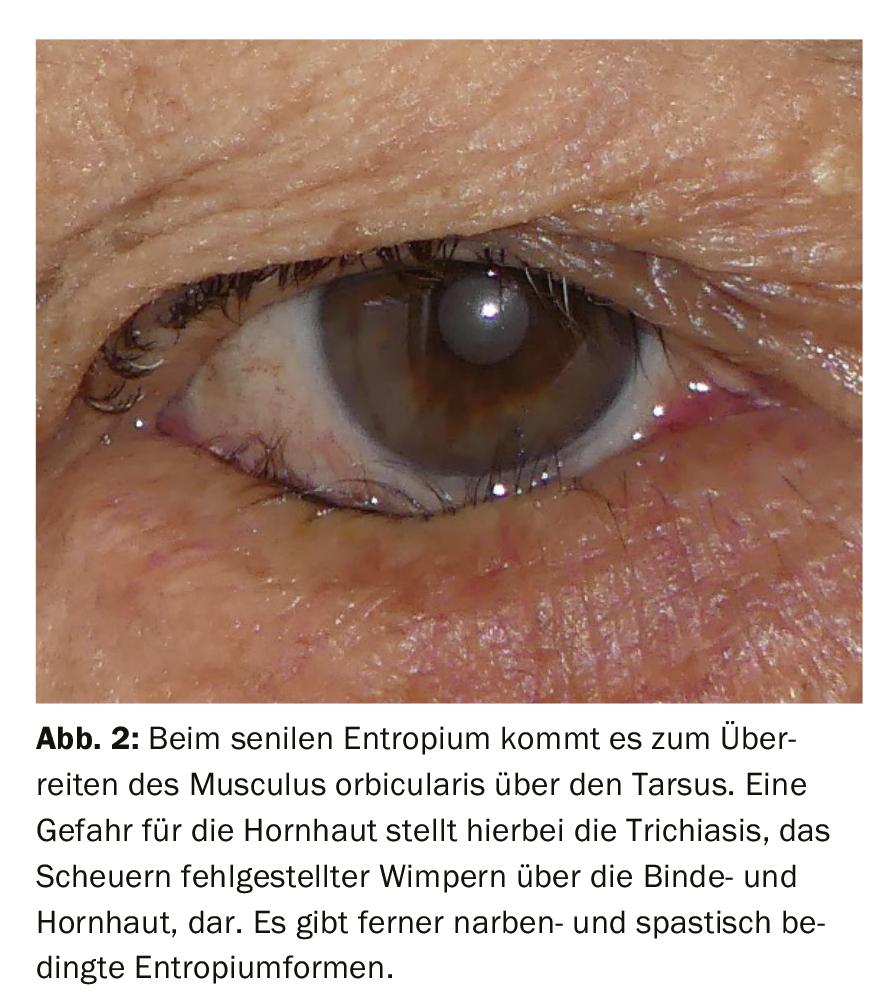

The time course is also crucial. If the problem has already existed for more than a week, it can be assumed to be a chronic problem. These include, for example, eyelid malpositions (entropion and ectropion, trichiasis, lagophthalmos), which can irritate the eye. These should also be evaluated by an ophthalmologist during the course to prevent corneal damage. Dry eye and non-acute endocrine orbitopathy also belong to chronic red eye.

Investigation

The type of redness alone can be very revealing, although the macroscopic view is often not sufficient. It is important to ectropionate the eyelids or at least to lift the upper eyelids in order to better assess the redness and to be able to differentiate between a redness of the eyelids or eyelid appendages with possibly accompanying reaction of the conjunctiva on the one hand and a primary affection of the eye bulb on the other hand.

Hyperemia is differentiated into ciliary, conjunctival and mixed. In the case of ciliary injection, a redness immediately adjacent to the corneal margin, involvement of the cornea or deeper structures (e.g., in uveitis) must be considered. Conjunctival injection indicates hyperemia of superficially located vessels, although here the distinction from deeper episcleral vessels may be difficult. Pain history for any episcleral vessel involvement in epi/scleritis should be included for evaluation.

Sectorial redness may occur in episcleritis and scleritis, hyposphagma, or the less common so-called superior limbal keratoconjunctivitis. Diffuse redness is the case in conjunctivitis (bacterial, viral or allergic), many forms of uveitis, dry eye, corneal involvement or trauma.

Concomitant swelling of the conjunctiva (chemosis) due to increased capillary permeability is caused by local noxae or inflammation, drainage disorders of lymph or venous blood, hormonal fluctuations or tumors and is thus quite nonspecific. However, it is more frequently observed in allergic reactions.

In addition to the general hyperemia, a closer look allows the form of redness to be further divided. For example, “sludging” is a phenomenon found in underlying systemic diseases, such as macroglobulinemias or sickle cell disease. Redness of the conjunctiva with telangiectasia of the surrounding lid skin may indicate blepharitis in rosacea.

Assessment of ocular secretions also helps etiologically.

In conjunctivitis of bacterial cause, the secretion appears yellow to greenish. Possibly even an emergence of pus from the lacrimal points can be observed or provoked in case of an involvement of the lacrimal ducts (canaliculitis). Spontaneous discharge or expressibility of pus from the tear points leads to the diagnosis. In viral conjunctivitis, watery to muco-yellow secretions are found.

A non-specific sign of irritation of the ocular surface is increased lacrimation (epiphora). In the case of inflammatory changes of the lacrimal gland, e.g. in Sjögren’s syndrome, this may be reduced or completely absent.

Unilateral or bilateral

Typically bilateral, but not always lateral, are endocrine orbitopathy, dry eyes, conjunctivitis (if not allergic possibly occurring with a time lag on the right and left side) and photokeratopathy (blinding). In particular, corneal disease, carotid sinus-cavernosus fistula, glaucoma, trauma/cauterization, and inflammation of the periocular structures must be considered as differential diagnoses in cases of strict unilaterality.

Palpation

Estimation of intraocular pressure with the index fingers on the lid of the eyelid while the patient is looking downwards when glaucoma is suspected is essential, always in lateral comparison. In case of elevated intraocular pressure, carotid sinus-cavernosus fistula must also be considered as a differential diagnosis.

As a general rule of thumb, patients with foreign body injury, acute visual loss, suspected corneal involvement, or ocular pressure problems should receive emergency ophthalmologic evaluation.

Extraocular clinical pictures

Dacryoadenitis is a circumscribed, painful inflammation of the lacrimal gland located under the upper outer eyelid. In addition to the reddening of the affected eyelid region, the so-called paragraph sign is characteristic, as the eyelid formation looks like a “§” tilted by 90°. Typical pathogens are staphylo- and streptococci as well as gram-negative bacteria [2]. Differentially, a lid phlegmon must be considered. Systemic antibiotic administration is indicated.

Dacryocystitis refers to an infection of the saccus lacrimalis that results in a pressured, reddened swelling inferonasal to the inner corner of the eyelid. Gram-positive pathogens are most commonly detectable, but Gram-negative bacteria are increased in cases of immunosuppression or diabetes mellitus. In advanced cases, surgical intervention may be necessary, but antibiotic systemic therapy is usually sufficient.

Hordeolum (sty) is a mostly bacterial inflammation of sebaceous or sweat glands at the edge of the eyelid and results in a localized, red swelling in the affected area of the eyelid. After appropriate therapy with heat application, e.g. by infrared light and local antibiotic therapy in the form of ophthalmic ointments, the findings usually heal well [3], sometimes a chalazion may remain as a consequence. If the findings persist, an ophthalmologic consult and histology should be performed if necessary [3]. On the other hand, if the findings are rather diffuse, lid phlegmon should be excluded, which also requires emergency presentation to an ophthalmologist and systemic antibiotic treatment (Fig. 1).

Chalazion (hailstone), unlike hordeolum, is a noninfectious and nonpainful localized granulomatous inflammation. It may persist after healed hordeolum as a consequence or may arise primarily in congested glands. Typically, patients are primarily cosmetically disturbed. However, not only this, but also the histological differentiation from adenocarcinoma may indicate minor surgery with pathohistological examination in case of persistence and increase in size.

One danger of eyelid malpositions is drying of the surface with damage to the cornea and resulting visual impairment. This is especially true for lagophthalmos, a defect in eyelid closure that can occur, for example, after facial nerve palsy, and entropion, because the inwardly protruding edge of the eyelid causes the eyelashes to rub against the cornea, which in the worst case can result in a corneal ulcer. (Fig. 2). An ophthalmological check-up is therefore always indicated. The situation is less dramatic in ectropion, an outward sweeping of the eyelids. Patients usually complain of epiphora (increased tearing). However, in advanced cases, insufficient moistening of the ocular surface and, in extreme cases, lagophthalmos may occur, endangering the cornea.

The case of fistula formation between the cavernous sinus and the internal carotid artery (carotid sinus-cavernosus fistula) is usually preceded by trauma, but it may also arise spontaneously. Complaints may include a feeling of pressure, worsening of visual acuity, double vision and headache. Objectifiable are clearly dilated and tortuously configured episcleral vessels, a more or less pronounced pulse synchronous exophthalmos, motility restriction and auscultable murmurs over the closed lid. Further imaging and management by an interdisciplinary center are mandatory, as neuroradiologic intervention may be inevitable depending on the subtype of fistula [4].

Eyelid rim inflammation (blepharitis) is an acute or, more commonly, chronic inflammation of the skin-conjunctiva junction with involvement of the appendages (meibomian, Zeiss and Moll glands). It may occur in isolation, clustered in the elderly population, or in certain groups of patients (e.g., with diabetes or with rosacea). There are associations with demodex mite colonization and dry eyes. Treatment options consist of eyelid margin hygiene, in cases of suspected demodex infestation with additional application of, for example, tea tree oil-containing care products, in severe cases local antibiotics or even systemic tetracyclines. Long-term, combined therapeutic approaches are common and interdisciplinary collaboration with dermatology may be useful [5].

Diseases of the conjunctiva

Conjunctivitis is largely treated in the primary care physician’s office rather than directly by the ophthalmologist [6]. Among the non-infectious causes, allergic conjunctivitis plays the most important role; among the infectious ones, viral conjunctivitis is the leading cause. In general, these potentially highly contagious patients should be physically separated from other patients, for example in separate waiting areas, and any contaminated surfaces should be well disinfected.

In most cases conjunctivitis is harmless and self-limiting, but certain forms can lead to corneal involvement and visual impairment. Contact lens wearers represent a special risk group here.

The symptomatology is diagnostic. What they all have in common is conjunctival injection with more or less pronounced accompanying swelling of the eyelids. Viral conjunctivitis primarily results in watery secretions and itching, but the severity of symptoms can vary widely; in certain forms, glare sensitivity (photophobia) may also be present.

Bacterial conjunctivitis results in agglutinated eyelids with purulent or mucopurulent secretions, chemosis, and is less likely to show itching. Allergic conjunctivitis is characterized by itching, chemosis and epiphora.

Bacterial conjunctivitis in our latitudes is caused mainly by Staphylo- and Streptococci, and in childhood mainly by Haemophilus influenzae, Pneumococci or Moraxella species [5]. A conjunctival smear can often be falsely negative and is therefore indicated only in complicated, recurrent cases or in immunocompromised and neonates [7]. A large proportion has a self-limiting course. However, antibiotics lead to a reduction in the duration of the disease. Locally applicable broad-spectrum antibiotics are used, for example gentamycin, tobramycin or ofloxacin as eye drops. The use of eye ointment is contraindicated in children due to the risk of amblyopia. Conjunctivitis induced by sexually transmitted pathogens occupies a special position in therapy. These require systemic and partner therapy. Likewise, the history regarding the wearing of contact lenses is important, as here the indication for antibiotic therapy as well as for ophthalmologic co-evaluation is given more generously [7]. Immediate contact lens abstinence is mandatory.

The majority of conjunctivitis is viral, and of these, a large proportion are caused by the highly contagious, epidemic adenoviruses. Here, pharyngoconjunctival fever with preauricular lymph node enlargement, pharyngitis, fever, and conjunctivitis is distinguished from keratocojunctivitis epidemica, which may also be associated with lymph node swelling. The main risk of ophthalmologic complications is corneal involvement with so-called nummuli (immunologically induced subepithelial corneal infiltrates) or pseudomembranes (whitish fibrinous deposits in the fornix). Ophthalmologic control is indicated if symptoms persist for more than 5 days [3].

Likewise, referral to an ophthalmologist is always indicated in cases of suspected ocular involvement with herpes, as uveitis may be a complication in addition to corneal complications (Fig. 3).

Herpetic infections should be treated systemically and/or locally with antiviral therapy, whereas other viral conjunctivitis are treated only symptomatically and not causally. Above all, education regarding (strict) hygiene measures is important. Certificates of incapacity must be issued to limit the epidemic, and when patients are referred to the ophthalmology office to confirm the diagnosis of keratoconjunctitvitis epidemica, patients should be announced there so that appropriate precautions can be taken to protect other patients and staff.

Fungal or protozoal infections are very rare triggers for keratoconjunctivitis, but represent an important differential diagnosis in the context of trauma caused by organic foreign body material (mainly fungi) and in contact lens wearers (mainly acanthamoebae). Especially in connection with wearing contact lenses while bathing, it is necessary to think about the acanthamboid infection. Fungal and protozoal infections must be clarified ophthalmologically due to acute visual impairment [3].

Among noninfectious conjunctivitis, allergic (rhino)conjunctivitis is the most important. Here, type I reactions represent the largest proportion, whereas type IV allergies of the delayed (cell-mediated) type account for more severe chronic courses [8].

Triggering agents for type I allergies are mostly seasonal allergens. Findings include eyelid swelling, chemosis, conjunctival hyperemia, epiphora, pruritus, and burning sensation. Type IV allergies include atopic conjunctivitis and keratoconjunctivitis vernalis, which, in addition to typical allergic symptoms, may also present with mucus formation, photophobia, and blurred vision. Atopic conjunctivitis is associated with systemic atopy, primarily affecting young adults. Keratoconjunctivitis vernalis affects children (more commonly boys) with a positive (family) history of atopy. These clinical pictures have to be treated ophthalmologically, because they can have a visus-threatening course [8].

Therapeutic options include allergen avoidance, cold compresses, local and systemic antihistamines, tear substitutes, blepharitis therapy (eyelid margin care), hyposensitization and mast cell stabilizers (e.g., chromoglycic acid), and, in the short term, local steroids if necessary (not without ophthalmologic care) [8].

Due to an extensive hemorrhage under the bulbar conjunctiva, the patient often experiences a dramatic but objectively harmless finding of hyposphagmia. The most important thing here is to educate and reassure the patient, to rule out hypertensive derailment and, if necessary, to check anticoagulation.

Dry eye (keratoconjuntkivitis sicca) is probably one of the most common causes of bilateral eye redness. Complaints include burning sensation, foreign body sensation to pressure sensation and visual acuity fluctuations due to poor wetting of the ocular surface including the cornea. Therapeutically, tear substitutes are used, furthermore blepharitis therapy if necessary (see above). In case of pronounced foreign body sensation, reduced lacrimation and anamnestically reduced saliva production, a Sjögren’s syndrome must be considered as differential diagnosis.

Cosmetically disturbing for patients can be the reddening of the conjunctiva in the foreground, as in conjunctivitis, so that there is a desire for “whitening” substances. Here, vasoconstrictive eye drops, e.g., napahazoline or tetryzoline, are used, which, however, may lead to tachyphylaxis and, in turn, to the enhancement of keratokoinjunkitivis sicca, rarely also to pressure increase in narrow-angle disposition and, therefore, cannot be recommended without restrictions [3]. Consistent tear replacement therapy, preferably preservative-free, optimization of modifiable environmental factors (e.g., use of air conditioning), and treatment of any underlying diseases (e.g., rosacea) are paramount.

Orbital diseases

In Graves’ disease with manifestation in the eye (endocrine orbitopathy) , the inflammatory change in the eye muscles and orbital adipose tissue leads to painful eyelid swelling and redness, exophthalmos, eyelid retraction, and limitation of mobility, primarily during upward gaze, as the inferior straight eye muscle is usually affected first (Fig. 4) [9].

Diagnosis is made clinically and by laboratory chemistry via determination of TSH receptor antibodies. Risk factors include dysthyroid metabolism and nicotine abuse [9]. Different stages are classified, which decide on the procedure. Interdisciplinary cooperation is essential for this. While surface moisturizing therapy may be sufficient in the milder form, systemic steroid therapy and/or ophthalmic surgical intervention must be considered in the visually threatening form (see European Group On Graves Orbitopathy scheme: www.eugogo.eu). Differential diagnosis should include the less common idiopathic inflammatory orbitopathy, which is more often unilateral but primarily acute in nature.

Diseases of the cornea

The cornea is the most sensitive organ of the body. Superficial lesions of the cornea affecting only the epithelium result in very painful erosio corneae . Other symptoms are epiphora, marked redness and possibly chemosis of the conjunctiva. Fluorescein and red-free light can be used to assess the extent of the injury. Common accident mechanisms are injuries caused by foreign bodies, a remnant of which may still be found on the ocular surface. However, in neurotrophic keratopathy, diabetes mellitus, or advanced patient age, pain may be absent and without adequate trauma, erosions or even ulceration (corneal ulcer) may occur if deeper layers are affected. Intubated patients are also at increased risk. On the one hand, there is a risk of keratitis forming as soon as the corneal epithelium is injured; on the other hand, an ulcer can also develop on the basis of keratitis. If the history is positive for foreign bodies, ophthalmologic inspection must be performed promptly to rule out existing foreign bodies and penetrating injury requiring surgical intervention. Therapeutically, tear replacement therapy as well as local anitbiotics, especially ointments, and adequate pain therapy are used.

Infection of the cornea (keratitis) usually occurs after previous epithelial injury. In addition to the foreign body injury, the history regarding contact lenses is particularly relevant here. In Switzerland, approximately 46% of keratitis is contact lens-associated [10].

However, there are also a few pathogens that can penetrate intact epithelium, for example, hemophilus influenzae or corynebacteria. Due to the acute visual risk, an ophthalmologic evaluation is urgently indicated; if necessary, depending on the extent of the corneal infiltrate, it may require a smear collection and hospital admission for intensive drip therapy. If possible, contact lenses that may be contaminated should be saved for microbiological examination. In mild cases, outpatient antibiotic drip therapy may be used. However, particularly severe courses should be treated as inpatients, since emergency surgery with corneal transplantation (PKP à chaud) may be required in case of corneal melting.

Unprotected exposure to UV light (e.g., high-altitude sun, welding) results in blinding (keratopathia photoelectrica), keratitis punctata superficialis, which causes conjunctival redness, pain, photophobia, foreign body sensation, and epiphora, typically after a latency period of several hours [9]. Relatively rapid healing can be aided (in adults) by an eye dressing and pain medication; antibiotic eye ointments are used because of the increased risk of infection. This does not apply to children, in whom eye ointments and dressings should be avoided as far as possible because of the risk of amblyopia.

Acute diseases of the sclera, uvea and optic nerve, among others.

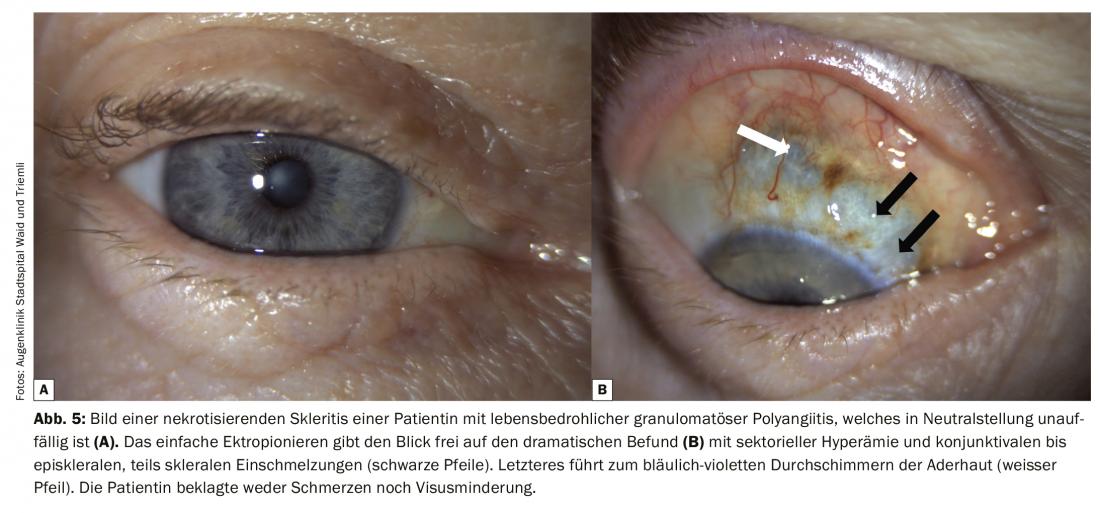

Scleritis (inflammation of the dermis) and episcleritis may appear macroscopically similar: diffuse or sectorial mixed injection. However, scleritis is typically much more painful, with patients feeling a dull pressure and being extremely sensitive to even careful palpation. Episcleritis can also be mildly painful, but eye movements and palpation are much better tolerated. Redness regresses with local phenylephrine application (vasoconstriction of superficial vessels by alpha1-receptor agonists). Depending on the form of the disease, systemic and local therapies (NSAIDs, steroid preparations if necessary) are decided upon and, if necessary, further infectious and/or rheumatologic diagnostics are initiated. Sometimes scleritis can be the first clinical sign of life-threatening systemic vasculitis (Fig. 5).

In addition to scleritis and episcleritis, there are other forms of intraocular inflammation, infectious as well as noninfectious, in which any segment of the eye, from the cornea to the retina, may be involved and therefore often not apparent to the general practitioner. When anterior segments of the eye are involved, redness of the eye may actually be a leading finding, but its absence does not rule out uveitis. Symptoms can vary from extremely painful with visual loss and photophobia to subjectively not very bothersome. Uveitis of the anterior and middle eye segment should always be considered as a differential diagnosis in case of photophobia, bulbar pain, new mouches volantes or visual loss, especially if the history does not allow other conclusions and/or rheumatologic diseases are already present. Posterior uveitis can be painless but with massive visual impairment.

Glaucoma is caused by aqueous humor outflow obstruction (acute angle or pupillary block) with severe intraocular pressure increase, which may lead to irreversible damage of the optic nerve with visual field loss. This leads to unilateral, possibly radiating bulbar and head pain, mixed injection of the conjunctiva, more or less pronounced epithelial and stromal edema of the cornea, light-rigid, wide pupil and rainbow vision (light sources appear with surrounding colored rings). Vegetative accompanying symptoms with vomiting and nausea can complicate the diagnosis [9].

The diagnosis is made by measuring the pressure. This can also be done by non-ophthalmologic medical personnel in case of pronounced pressure increase by palpation on the bulb over the eyelid while looking down. The affected eye palpates rock hard. In case of doubt, the opposite eye can be palpated for comparison; a difference corroborates the tentative diagnosis.

In case of clinical suspicion and lack of internal contraindication, the general practitioner or internist can already start systemic administration of carbonic anhydrase inhibitors, at best intravenously, if necessary perorally, which lowers the pressure via reduction of aqueous humor production. In the absence of contraindication and inadequate pressure reduction by acetazolamide, administration of mannitol may be considered. Pressure-lowering eye drops can also be used, but are less effective compared with systemic therapy.

All traumatic eye injuries must be evaluated ophthalmologically. In the case of superficial foreign body injuries, an attempt can be made to remove foreign bodies by rinsing and possibly swabbing with a cotton swab. However, if the accident mechanism indicates a possible penetration or perforation, any manipulation should be refrained from, an emergency referral to an ophthalmic clinic with an appropriate surgical offer should be made and a loose eye dressing, at best with a capsular dressing for protection, should be applied for the transport. In case of chemical burns, eye rinsing must be started before transport. It should be noted that alkalis can cause more profound damage than acids.

Take-Home Messages

- Avertable emergency ophthalmic diagnoses include: Glaucoma, keratitis (caveat: contact lenses), scleritis, carotid sinus-cavernosus fistula, endocrine orbitopathy, traumatic eye injury, and potentially complicated conjunctivitis such as keratoconjunctivitis epidemica.

- Warning symptoms that must be queried are: Visual acuity reduction, acute bulbar pain, acute photophobia.

- Ophthalmic medications with special caution in use: steroid-containing local therapy should not be used for more than 2 weeks without ophthalmologic control (Main risks: intraocular pressure increase, cataract development); ophthalmic ointments or dressings must not be used in children or only under certain conditions (risk of amblyopia); oxybuprocaine or other local anesthetic eye drops must never be given to patients due to severe undesirable side effects.

- Immediate emergency ophthalmological evaluation is necessary in case of: Trauma (in the case of chemical burns, however, transport only after initial extensive eye rinsing), suspected corneal involvement, acute visual loss/photophobia and acute bulbar pain.

Literature:

- Shields T, Sloane PD: A Comparison of Eye Problems in Primary Care and Ophthalmology Practices. Fam Med 1991; 23(7): 544-546.

- Carlisle RT, Digiovanni J: Differential Diagnosis of the Swollen Red Eyelid. Am Fam Physician 2015; 92(2): 106-112.

- Frings A, Geerling G, Schargus M: Red Eye: A Guide for Non-specialists. Dtsch Arztebl Int 2017; 114(17): 302-312.

- Henderson AD, Miller NR: Carotid-Cavernous Fistula: Current Concepts in Aetiology, Investigation, and Management. Eye (Lond) 2018; 32(2): 164-172.

- Cronau H, Kankanala RR, Mauger T: Diagnosis and Management of Red Eye in Primary Care. Am Fam Physician 2010; 81(2): 137-144.

- Kilduff C, Lois C: Red Eyes and Red-Flags: Improving Ophthalmic Assessment and Referral in Primary Care. BMJ Qual Improv Rep 2016; 5(1).

- Messmer EM: Bacterial Conjunctivitis – Diagnosis and Therapy Update. Clin Monbl Ophthalmic 2012; 229(5): 529-533.

- Messmer EM: Ocular Allergies. Ophthalmologist 2005; 102(5): 527-543; quiz 544.

- Gorsch I, Haritoglou C: Ophthalmology in General Practice. MMW Fortschr Med 2017; 159(Suppl 3): 61-70.

- Bograd A, et al: Bacterial and Fungal Keratitis: A Retrospective Analysis at a University Hospital in Switzerland. Clin Monbl Ophthalmology 2019; 236(4): 358-365.

FAMILY PRACTICE 2020; 15(5): 8-14