Pulmonary rehabilitation is a cornerstone in the treatment of advanced chronic lung disease. It improves performance, quality of life and risk of hospitalization. Hardly any drug shows a comparably positive effect.

Using COPD as an example, it has been shown that the extent of physical activity is the most important predictor of survival, ahead of FEV1 [1]. Similarly, we know about the association between physical activity and exacerbation risk [2].

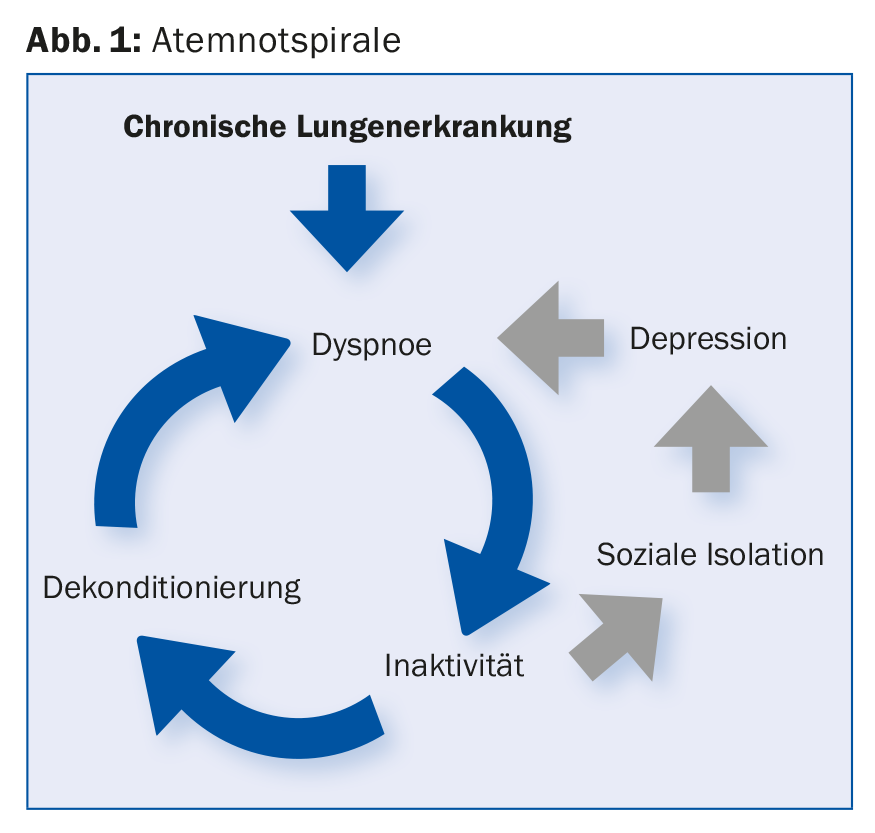

However, people with chronic lung disease avoid physical exertion whenever possible, which in turn exacerbates exertional dyspnea via consecutive deconditioning. This describes the so-called breathing spiral (Fig. 1) . A vicious circle that is intensified by anxiety and depression as well as social withdrawal and can hardly be broken independently.

This is where pulmonary rehabilitation steps in, offering a tailored program to help the unsettled sufferer gain more confidence in their own body and thus lead a sustainably active life.

Indications and evidence base: COPD

Much of the evidence on the effectiveness of pulmonary rehabilitation involves patients with COPD-who also make up the vast majority of participants.

Mortality and hospitalizations: In 2011, a Cochrane review of nine studies demonstrated an impressive benefit in terms of both mortality (NNT 6) and rehospitalizations (NNT 4) for pulmonary rehabilitation after acute COPD exacerbation [3].

A 2016 update by the same authors with 11 additional studies confirmed the benefit. However, the result was less clear, especially with regard to mortality, which can be partly explained by structural heterogeneity of rehabilitation programs [4].

Physical performance and quality of life: a meta-analysis of 65 randomized controlled trials involving a total of 3822 patients with advanced COPD sheds light on quality of life and performance. Pulmonary rehabilitation – whether inpatient or outpatient – can significantly improve quality of life. At the same time, both maximal exercise capacity in ergometry and functional performance in the 6-minute walk test can be significantly increased [5].

Indications and evidence base: other lung diseases

Interstitial lung disease: It is also well established that pulmonary rehabilitation for interstitial lung disease improves both quality of life and functional capacity. The effect can be demonstrated in all subgroups despite the heterogeneity of the disease pattern, but decreases with disease severity [6].

Asthma: Regular physical training is also important in bronchial asthma, because in addition to a significant increase in quality of life, symptom-free days as well as anxiety and depression can be improved [7]. In stable asthma, advice to engage in regular physical activity, such as going to a gym, is usually sufficient. However, it is not uncommon for mildly affected individuals to be so distressed that medical training therapy is necessary to bridge the gap to independent training. In severe or unstable cases, structured and comprehensive pulmonary rehabilitation care is recommended.

Bronchus carcinoma: With intensive preoperative rehabilitation over two to four weeks, patients with bronchus carcinoma who are primarily inoperable can be brought to an operable state (measured by VO2 max). Postoperatively, exercise capacity, dyspnea, and fatigue can be improved. Accompanying chemotherapy – provided that adherence is not too severely limited by side effects – an improvement of symptoms and a preservation of performance can be expected [8].

Requirements

Optimized drug therapy is a prerequisite for the best possible rehabilitation success. In addition, comorbidities such as osteoporosis, cardiovascular diseases or restrictive orthopedic problems must be systematically recorded and treated beforehand.

Patient selection: Pulmonary rehabilitation in patients with COPD is indicated from risk class B according to GOLD and can be started in the stable interval as well as following an acute exacerbation. For other chronic lung diseases, pulmonary rehabilitation is appropriate when the disease results in a reduction in quality of life.

The severity of the underlying disease, comorbidities, psychosocial problems, a long commute, and active smoking are risk factors for rehabilitation dropout. However, from experience, none of these criteria can predict adherence with sufficient reliability to warrant primary exclusion. It is not uncommon for us to experience surprisingly positive developments despite unfavorable conditions, which also have a motivating effect on the entire team. It is therefore worthwhile to enroll patients very generously in a program, but to accept occasional discontinuation in return.

Contraindications: Pulmonary rehabilitation is contraindicated in unstable cardiovascular disease. However, invalidating orthopedic problems or a massively limited willingness to cooperate can also occasionally lead to exclusion.

Assessments: For optimal exercise planning and exclusion of exercise-induced cardiac ischemia, ergometry should be performed at baseline, and spiroergometry should be performed if there are specific questions. A questionnaire to assess anxiety and depression, such as the HADS (Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale), is also recommended at least initially. The 6-minute walk test is standard for monitoring the success of physical performance. Meanwhile, also common and easy to perform is the 1-minute sit-to-stand test (STS). The constant-load cycle test is also scientifically reliable and well reproducible. The Chronic Respiratory Questionnaire (CRQ) has become established in Switzerland as a disease-specific questionnaire for assessing and monitoring quality of life.

Setting

Outpatient vs. inpatient: If possible, an outpatient setting should be sought because training close to everyday life facilitates the transition to a long-term active lifestyle. In addition, the outpatient implementation of the rehabilitation with a program duration of twelve weeks enables an optimal training build-up – we know from studies that the performance increase subsequently plafonates. From an exercise physiology point of view, at least two, preferably three training sessions per week are recommended.

Severely limited mobility, whether due to the severity of the underlying disease or comorbidities, argues for an inpatient setting. Difficult psychosocial circumstances can also be a reason for the more cost-intensive inpatient option. Often, immediately following an inpatient program, outpatient continuation of pulmonary rehabilitation is appropriate for the above reasons.

Accredited centers: Outpatient and inpatient programs are now offered throughout Switzerland. A list of all accredited centers can be found on the homepage of the Swiss Society of Pneumology (www.pneumo.ch/de/pulmonale-rehabilitation.html).

Rehabilitation program

There is no “one size fits all”. To achieve maximum success and long-term health-promoting behaviors, a comprehensive program must be tailored to each individual’s capabilities and needs, and continuously adjusted.

Endurance training: Effective endurance training must be significantly higher in dosage than everyday exercise, and the patient should experience moderate to severe dyspnea according to the Borg scale. Endurance training at this high level is only possible with trained and intensive physiotherapeutic care. A continuous load on the bicycle ergometer for 30 minutes to 60-80% of the maximum power is usual [8]. Depending on personal preferences or, for example, in the case of orthopedic problems, treadmill training is an alternative. Often patients are unable to exert themselves consistently for 30 minutes. In this situation, high-intensity interval training is just as effective as continuous exercise. However, due to the recovery phases, it is better tolerated, especially with regard to effort dyspnea [8].

Very much appreciated by our participants is the once a week Nordic Walking on our rehabilitation trail. It allows training that is close to everyday life – for example, on the subject of how to behave on an incline – and takes away the fear of exerting oneself outdoors even in adverse weather conditions.

Strength training: Strength exercises cause less exertional dyspnea than endurance training, so a greater increase is often possible here. One to three sets of eight to twelve repetitions each at an intensity of 60-70% of the “one repetition maximum” (maximum weight that can be moved in one repetition) are recommended [8].

Other training aspects: In the case of severely impaired performance, alternative training methods such as neuromuscular electrical stimulation, whole-body vibration or eccentric treadmill training (“downhill walking”) can be used. Inspiratory muscle training in addition to endurance and strength training may provide benefit in COPD and relevant inspiratory respiratory muscle weakness (PI max <60%) [9].

Accompanying program: Accompanying training in COPD strengthens the understanding of the disease and the personal responsibility of those affected. In Switzerland, the training program “Better Living with COPD” is widely used. In addition, the exercise program should be supplemented with smoking cessation or nutrition counseling, if necessary. Experience has shown that psychological counseling, which is readily available, is also valuable, because disease-associated anxiety in particular can be a great hindrance to physical training.

Sustainability: At the end of pulmonary rehabilitation, follow-up training must be planned. The focus should be on the patient’s practicality and preferences in order to increase physical activity in the long term and thus maintain the success of pulmonary rehabilitation. Structured follow-up programs facilitate the continuation of regular physical activity, because often daily fluctuations due to illness make it difficult to maintain self-discipline for independent training. As a result, about two-thirds of former participants in our outpatient pulmonary rehabilitation program attend our twice-weekly group training sessions, often for years, as self-pay patients.

Take-Home Messages

- Pulmonary rehabilitation is a cornerstone in the treatment of advanced chronic lung disease. It has been a mandatory health insurance benefit in Switzerland since 2005.

- Pulmonary rehabilitation is recommended for COPD with risk class B or higher according to GOLD. It improves physical performance, quality of life and risk of hospitalization. Hardly any drug shows a comparably positive effect.

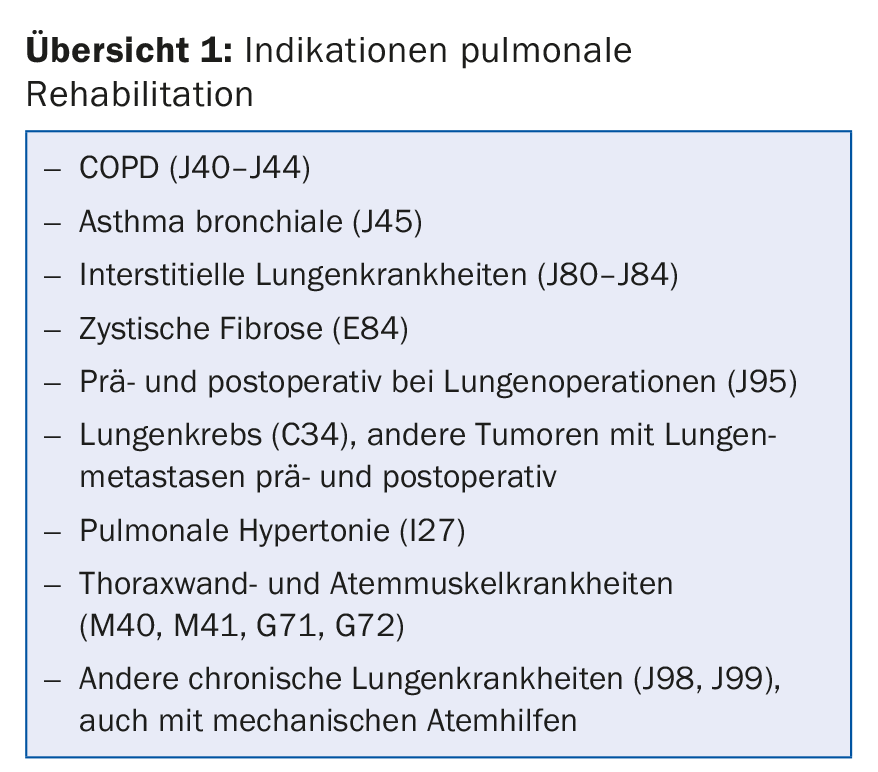

- Pulmonary rehabilitation has also been shown to be effective in other chronic lung diseases (review 1).

Literature:

- Waschki B, et al: Physical activity is the strongest predictor of all-cause mortality in patients with COPD: a prospective cohort study. Chest 2011 Aug; 140(2): 331-342.

- Gimeno-Santos E, et al: Determinants and outcomes of physical activity in patients with COPD: a systematic review. Thorax 2014; 69: 731-739.

- Puhan MA, et al: Pulmonary rehabilitation following exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2011 Oct 5; (10): CD005305.

- Puhan MA, et al: Pulmonary rehabilitation following exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2016 Dec 8; 12: CD005305.

- Mc Carthy B, et al: Pulmonary rehabilitation for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2015 Feb 23; (2): CD003793.

- Downman L, et al: The evidence of benefits of exercise training in interstitial lung disease: a randomised controlled trial. Thorax 2017 Jul; 72(7): 610-619.

- Mendes FA, et al: Effects of aerobic training on psychosocial morbidity and symptoms in patients with asthma: a randomized clinical trial. Chest 2010 Aug; 138(2): 331-337.

- Spruit M, et al: An Official American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society Statement: Key Concepts and Advances in Pulmonary Rehabilitation. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2013 Oct 15; 188(8): e13-64.

- Gosselink R, et al: Impact of inspiratory muscle training in patients with COPD: what is the evidence? Eur Respir J 2011 Feb; 37(2): 416-425.

HAUSARZT PRAXIS 2017; 12(12): 19-21