On April 10, 2014, the fifth annual symposium of the Swiss Society for Anxiety and Depression (SGAD) was held at the Dolder Grand Congress Center in Zurich. High-profile speakers provided information on current therapies, epidemiological trends, and future prospects regarding drug treatment.

(ee) The anniversary symposium was opened by former President of the Swiss Confederation Hans-Rudolf Merz with an entertaining talk about his own borderline experiences. This included, for example, witnessing an air raid in Lebanon in 1982 and thus the beginning of the Middle East war, or being confronted much later with construction plans for a nuclear bomb during a Federal Council meeting – knowing that these plans would have been delivered to a dictator suspected of terrorism. The description of the banking crisis in 2008, which triggered a cardiac arrest with a four-day coma for Merz, who was finance minister at the time, was also impressive. “Afterwards, I read several books about near-death experiences,” Merz recounted, “but I couldn’t relate to them at all, because I hadn’t experienced anything like that.” For him, who does not believe in an afterlife, this drastic experience meant one thing above all: to pay even more attention to the way he leads his life, so that he does not miss out on the joy of living.

Depression and anxiety disorders in childhood and adolescence

Anxiety disorders occur in about 11.5% of children and adolescents, depression in 1-5% and ADHD in 2-5%, informed Prof. Dr. med. Dipl. Psych. Susanne Walitza, medical director of the KJPD at Zurich University Hospital. Public perception focuses on ADHD, although anxiety disorders are much more common. The majority of children under 12 suffer from separation anxiety (4%), so that they cannot attend kindergarten, for example. In adolescents, specific phobias (16%) and social phobias (7%) are most common, with prevalence decreasing with age. Girls are more often affected by depression and anxiety symptoms than boys. In addition to a detailed medical history, a screening with specific questionnaires or a diagnostic test is also required to establish the diagnosis. Assessment instruments used. Close caregivers should also always be consulted, and in some cases a school visit is also recommended. Children with anxiety disorders hardly present more conspicuously than other children apart from the disorder. In contrast, children with depression are more likely to show significant abnormalities (higher impairment, more negative family climate, mental health comorbidities).

Treatment is based on three pillars: Psychoeducation, behavioral and psychotherapy, and medication. “Psychoeducation is about, among other things, explaining to parents that they haven’t done everything wrong in parenting,” Prof. Walitza said. “There is a strong genetic component in anxiety disorders, up to 70% in separation anxiety.” Among psychotherapies, cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) has Level I evidence; it is the first-choice therapy for children and adolescents. However, there is limited evidence based on recent studies that CBT works better than other active therapies. In Zurich, for example, social phobias are treated with the “Don’t be a frog” program. This is suitable for children between the ages of seven and twelve and involves approximately 20 sessions at weekly intervals, four of which are parenting sessions.

Medication in children and adolescents is useful in cases of unsuccessful psychotherapy, in very severe cases, or in situations when medication makes participation in psychotherapy possible in the first place. SSRIs are effective, whereas imipramine, other tricyclics, and benzodiazepines are not recommended. A positive effect was shown in studies primarily with fluoxetine, and in a Cochrane analysis also with fluvoxamine. In a recent study by Zhang et al. however, acceptance and tolerability were higher for sertraline, paroxetine, escitalopram, and venlafaxine. The combination of medication and CBT is still considered most effective (71% response rate, floxetine only 60%, CBT only 43%). Suicidality does not increase with the administration of a drug, according to the latest studies; only with combination drug therapies is there a higher rate of suicidal behavior.

Epidemiological research: current and relevant for practice

Prof. Dr. med. Jules Angst, Psychiatric University Hospital Zurich, gave an interesting insight into the “Zurich Study”, which was conducted between 1978 and 2008 with about 300 men and women each. Participants were 20 years old at the start of the study, and they were interviewed on average every four to five years about depression and anxiety disorders. In 2008, 57% of the participants were still there. The Zurich study is the only study in the world with so many patient interviews over 30 years.

The cumulative incidence of anxiety disorders is over 40%, and for affective disorders it is 35. Generalized anxiety disorders (GAD) increase sharply after age 30, unlike other anxiety disorders. All the disorders studied occur less frequently in men than in women, with the exception of mania, where the ratio is 1:1. The treatment prevalence for depression in women is 44%. Most diagnoses are made only once, so they are episodic disorders that go away. Interestingly, anxious individuals showed a higher survival rate, for all causes of death. “Evolutionarily, fear does make sense, because it still exists today,” Prof. Angst said. “Anxiety protects people, and possibly anxious people have a survival advantage because they live a more cautious lifestyle.” People with GAD or panic attacks show the same comorbidity pattern. This fact indicates a common biological origin of these diseases. There are also commonalities in bipolar disorder and depression.

The level of suffering in people with the disease is independent of the duration of the disease – similar to pain disorders. “Therefore, the diagnostic criteria of duration of two weeks for major depression and three and six months, respectively, for GAD are not valid,” the speaker opined. He proposed four days for depression and two weeks for GAD as new criteria. This proposal should be tested by independent studies. Prof. Angst recommended not only to determine the length of the episodes, but also to ask the patient how many days a year he or she is disabled by the condition and how severe the suffering is (e.g., with an analog scale). This is because for all mental and somatic syndromes that produce subjective symptoms, the need for treatment correlates most strongly with the level of suffering. However, this criterion fails e.g. in hypomania/mania, in psychotic syndromes and in addictive disorders, because there is no feeling of sickness resp. there is no insight into the disease.

How will we treat anxiety and depression in ten years?

Prof. Dr. med. Florian Holsboer, Max Planck Institute for Psychiatry, Munich, ventured a look into the future. In Europe, the lifetime prevalence for affective disorders is 16.3% (U.S. 21, Japan 5.6) and for anxiety disorders 19% (U.S. 25, Japan 4.7). However, these high values should not tempt us to trivialize depression, because it is a very serious illness for anyone affected by it. Antidepressants lead to recovery in 70% of patients, but it takes too long for the drugs to work, and they have too many side effects. Therefore, research in the field of antidepressants is urgently needed. Prof. Holsboer explained some other areas of research:

- Depressed patients often have elevated levels of corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH) in the cerebrospinal fluid. Stress increases the release of CRH, which makes people fit to cope with threatening situations: Anxiousness increases, sleep is disturbed, sexual drive is lost – and the risk of depression increases. CRH blockers may eventually work in individuals with elevated CRH levels, and there are already positive research results in mice.

- The clinical effect of antidepressants is determined, among other things, by the genetically determined efficiency of the “guardian molecules” in the brain. These molecules protect the brain from foreign substances by preventing their entry through the blood-brain barrier. The more efficient the sentinel molecules, the more inefficient the therapy. Genetic tests that determine the efficacy of the sentinel molecules could help physicians make decisions.

- So-called. Chaperone molecules, e.g. FKBP5, determine which function the glucocorticoid receptor performs. Individuals with FKBP5 risk type have an increased risk for depression, thus FKBP5 may be suitable as a drug target. Molecules that antagonize FKBP5 could prevent stress-related diseases (e.g., post-traumatic stress disorder or depression).

In the future, it will probably be possible to better distinguish different patient populations, e.g., using EEG or genetic testing. As a result, medications can also be used more specifically. The speaker expects innovations above all from human genetics and genomics, from biomarkers that map pathophysiology (imaging, hormones, EEG), and from chemical biology.

DSM-5 and ICD-11: What you need to know for practice

Prof. Dr. med. Erich Seifritz, Psychiatric University Hospital, Zurich, closed the symposium by explaining the development of DSM-5 and ICD-11 and the innovations of DSM-5. Diagnostic classification systems have various functions, including improving communication and deriving therapies from a diagnosis. ICD was developed by WHO, DSM by the US American Psychiatric Association (APA). Initially, DSM reliability was low, especially for diagnoses based on concepts (e.g., “neurotic depression”). Since 1991, there has been formal convergence between ICD (ICD-10) and DSM (then DSM-3R). ICD-11 is expected to be published in summer 2015.

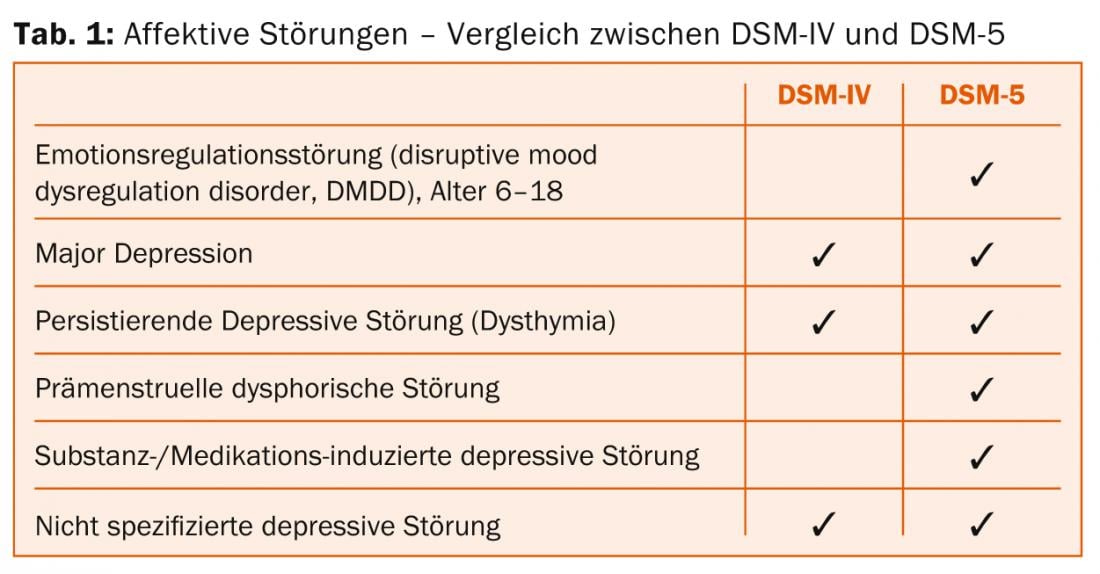

DSM-5 was published in May 2013. A new feature of affective disorders is the division of depressive and bipolar disorders into two chapters. The extent of anxiety disorders is specified in more detail, and a four-point qualitative suicidality scale is found for suicidality. New diagnoses include emotion regulation disorder in children and adolescents (DMDD), premenstrual dysphoric disorder, and substance/medication-induced depressive disorder (Table 1). DMDD replaced the previous diagnosis of bipolar disorder in children and adolescents, which was dropped. For a diagnosis of major depression, the exclusion criterion of “simple grief” is dropped in DSM-5. Severity and psychotic symptoms in major depression are separated in DSM-5.

Allen Frances, the author of DSM-IV, strongly criticizes DSM-5, including in his book “Normal” (Dumont Publishers). His main criticism is against the diagnosis of DMDD and the omission of the exclusion criterion “simple grief” in major depression. This would “medicalize normality.” Prof. Seifritz formulated his counterarguments clearly:

- DSM-IV caused something of an epidemic of bipolar disorder in children. Within a decade, the diagnosis of “bipolar disorder” in children increased 40-fold, including indications for atypical neuroleptics in children (with known problems and potential dangers such as unclear effects on brain development, metabolic syndrome, etc.). That’s what the DMDD diagnosis is trying to get away from.

- In DSM-5, the exclusion criterion of “simple grief” is dropped for major depression because it was not clear why grief for a loved one should exclude depression but grief for other serious life events (serious accident, cancer, job loss) should not.

- According to DSM-IV, 46% of the U.S. population has a diagnosable psychiatric diagnosis at some point in their lives; with DSM-5, the number is even higher. But should that be a problem? For influenza, there is a lifetime prevalence of 100% – and yet no one claims that this disease is diagnosed too often and is therefore not a disease at all. If criticism is made that with DSM-5 too many people received a psychiatric diagnosis, this is more an expression of the stigmatization of mental illness.

Source: Annual Congress of the Swiss Society for Anxiety and Depression (SGAD), April 10, 2014, Zurich.

InFo Neurology & Psychiatry 2014; 12(3): 32-34.