Epidemiology speaks a serious word: Otitis media (OM) is the most common occasion for antibiotic treatment in infancy, with 71% of all children undergoing acute otitis media (AOM) during the first 24 months of life, half of whom experience more than three episodes of AOM. And both AOM and its chronic forms can cause life-threatening complications. Encouragingly, there has been a sharp decline in OM prevalence since 1990-due primarily to pneumococcal and influenza vaccination (highly efficient especially LAIV) and decreasing cigarette smoking exposure.

Otitis media is defined as any inflammatory disease of the middle ear spaces. Etiopathogenetically, we differentiate acute suppurative OM from acute viral OM; clinically, acute OM (AOM) from chronic OM (COM), from which a common chronic tympanic effusion, sero-muco-tympanum must be strictly distinguished.

Bacterial isolation succeeds in 70-90% of all AOM, with pneumococci and unencapsulated (therefore not reached by vaccination) Haemophilus influenzae and Moraxella catarrhalis predominating. Almost regularly, AOM is preceded by a viral upper respiratory tract (IOL) infection, the most common agents of which are RSV and rhino viruses.

The typical clinical symptoms of AOM – in the context of an IOL – are fever and feeling sick, plus diarrhea and vomiting in infants and young children. An “ear twinge” occurs in only 10% of cases. In adolescents and adults, earaches and headaches, associated with hearing loss, are imposing. Absence of tympanic effusion (“politzer” in older children) certainly rules out AOM. The diagnosis is confirmed by ear microscopy/ otoscopy. Important complications should always be ruled out by palpation of the mastoid, examination of the facial nerve, and a hearing test (e.g., after four to twelve weeks).

Therapy of otitis media

Uncomplicated and primary complicated AOM: Therapy of uncomplicated AOM is by decongestants (without benzalkonium chloride) and systemic analgesics (1st choice: ibuprofen, substitute: paracetamol). Topical local anesthetics and/or antibiotics should be avoided. Due to the limited data available, the guideline committees have not made recommendations on any complementary/alternative therapies.

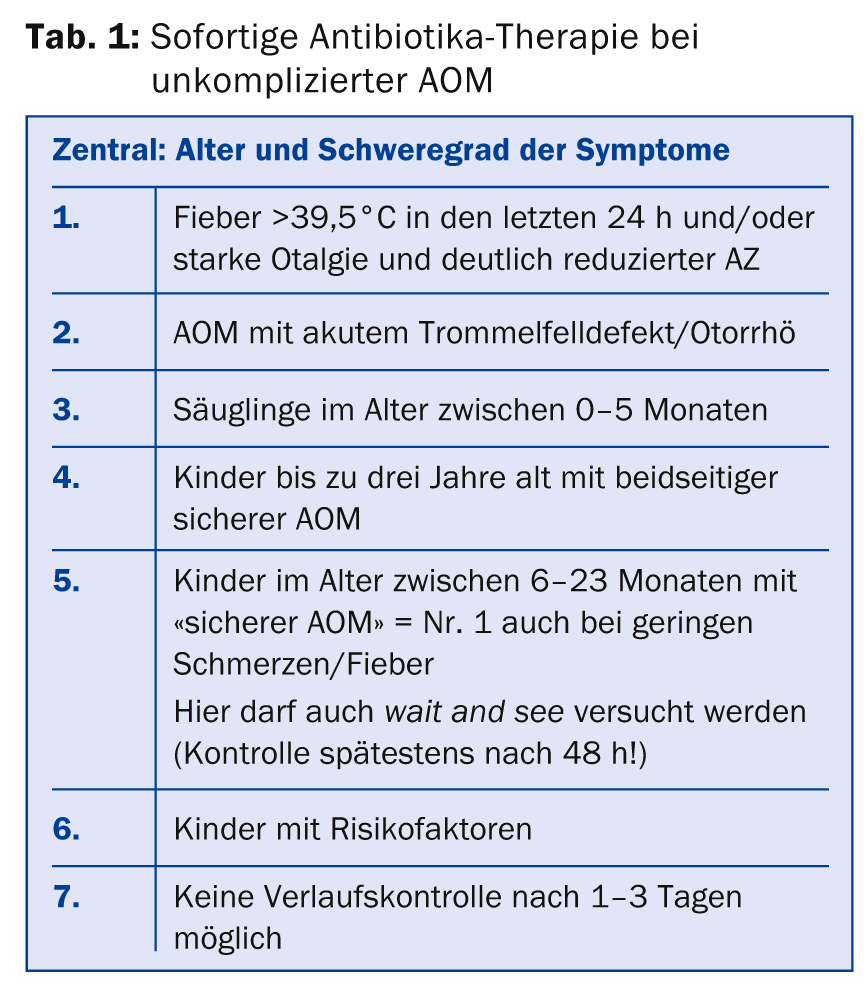

Since spontaneous regression of symptoms and findings occurs within 24 hours in 60% of AOM cases (after three days in 80, after four to seven days in 90% of cases) and further severe complications such as mastoiditis and brain abscess have become very rare, immediate antibiotic administration should not be performed in every case. Table 1 lists the cases in which immediate antibiotic therapy must be given.

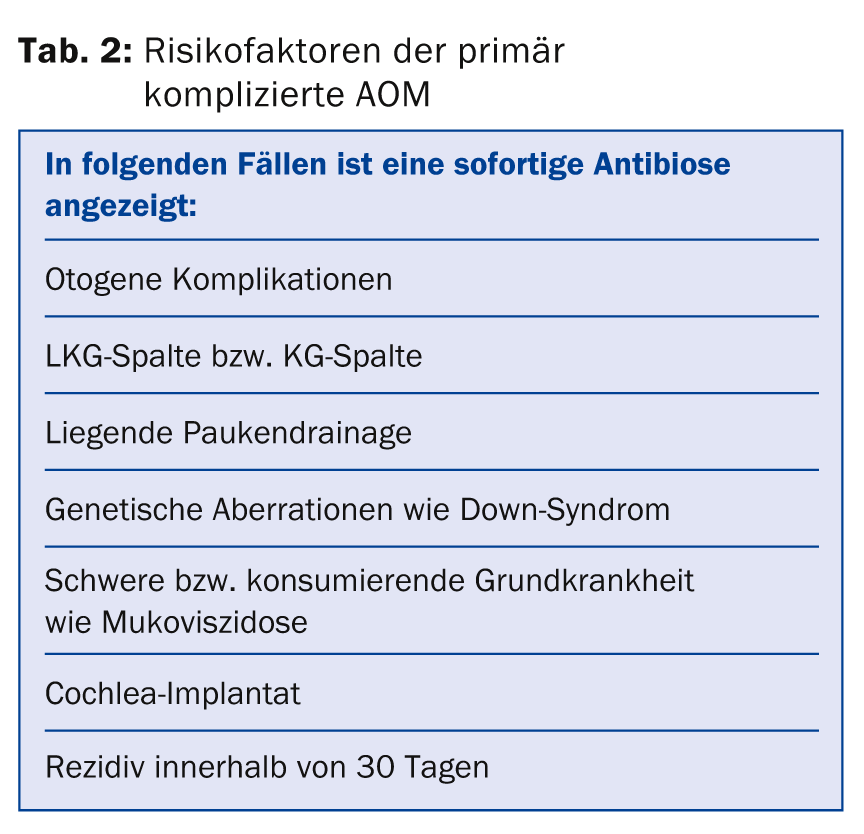

Table 2 provides information on the risk factors for primary complicated AOM, in which case immediate antibiotic treatment is also indicated.

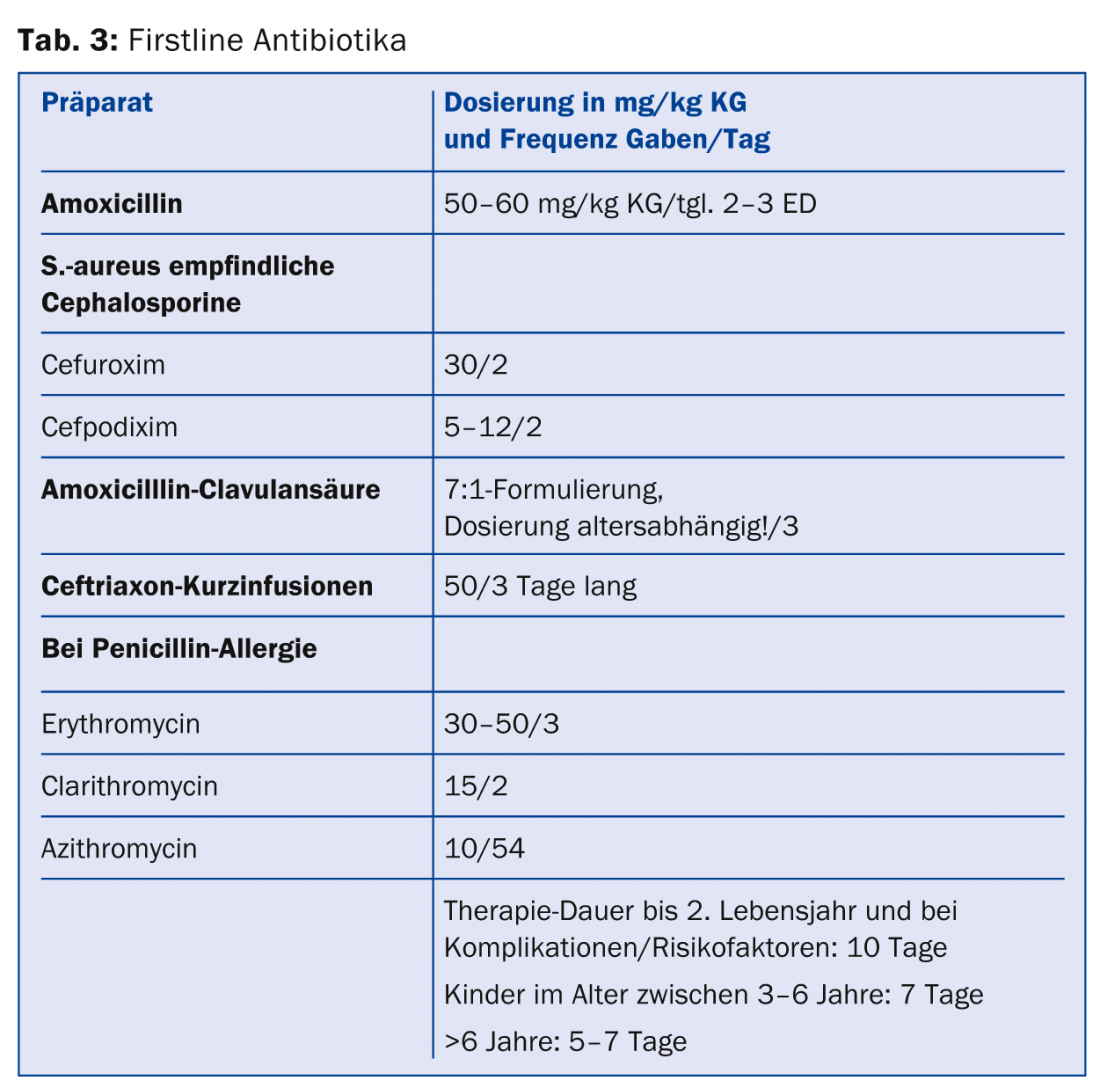

If no improvement can be achieved with a 2-step antibiosis (Tab. 3) according to these schemes, surgical measures should be initiated: Paracentesis as well as smear collection and further antibiosis appropriate to the pathogen.

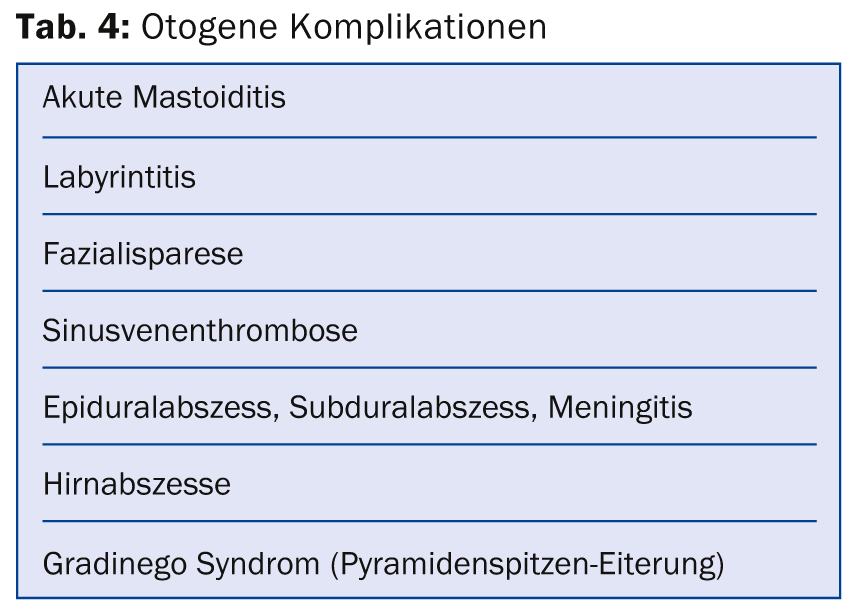

Surgical intervention must always be considered for otogenic complications as well; these are listed in Table 4.

Recurrent AOM: By definition, these are present when at least three AOM have been diagnosed within six months or four AOM have been diagnosed within twelve months. Then an underlying allergic disease should always be excluded, as well as the presence of an immunodeficiency. Pneumococcal and influenza vaccinations should be supplemented in this high-risk group with a paucendarinage and possibly an adenotomy (AT). This reduces the risk of AOM by 1.5/6 months. AT alone does not cause a reduction in AOM. Low-dose antibiotic administration over a longer period of time does not show positive effects.

Progress controls and efficient prevention

Whenever no primary immediate antibiotic treatment had to be initiated, a clinical control examination should be performed after two to three days (or earlier if necessary) to reassess the need for antibiotic use. Regardless of the form of therapy chosen, its efficiency and clinical course should be reviewed five to eight days after the start of therapy and the treatment adjusted if necessary. Hearing and speech development should be checked for the first time in every case of AOM one to three months after the end of therapy. Further diagnostic and therapeutic measures (including surgical: paracentesis, tympanic drainage, AT) may then need to be discussed.

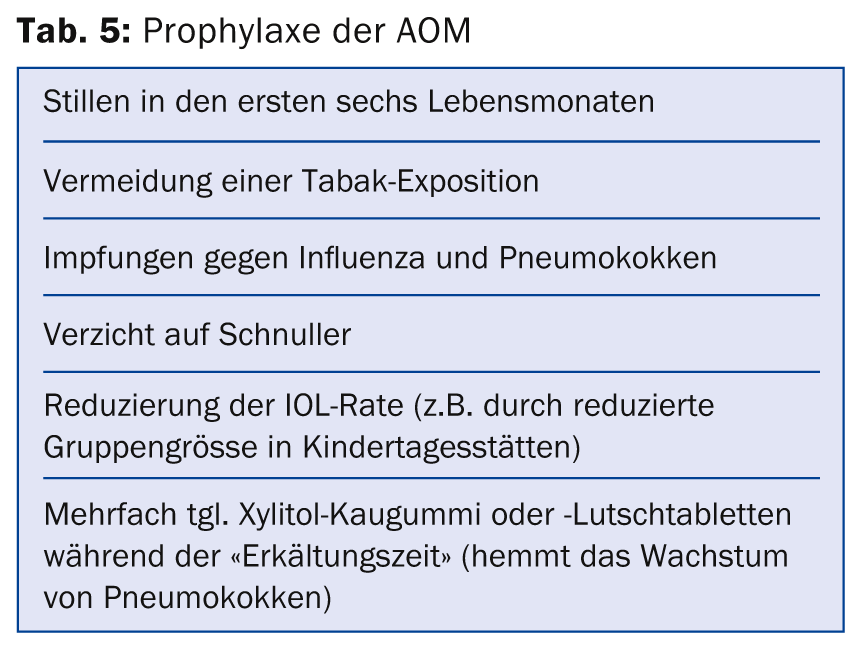

Effective prevention is based on knowledge of the risk factors. Not to be influenced are: Genetic predisposition, prematurity, male gender, ethnicity, number of siblings, and socioeconomic status. As prophylaxis of AOM, factors such as breastfeeding during the first six months of life, avoidance of tobacco exposure, and vaccination against influenza and pneumococcus have been shown to be effective in studies. The complete list can be seen in Table 5.

Conclusion for practice

- The biggest change in the treatment of OM occurs with regard to the use of antibiotics.

- In uncomplicated AOM from the third year of life, with confirmed close clinical control also for the age group six months to two years, no primary antibiotic administration should be given.

- The high efficiency of vaccinations (pneumococcus and influenza) in prophylaxis and the low value of (sole) adenotomy should also be taken into account in daily practice.

Literature (abbreviated):

- Lieberthal AS, et al: The diagnosis and management of acute otitis media. Pediatrics 2013: 131: e964-999.

- Uitti JM, et al: Symptoms and otoscopic signs in bilateral and unilateral acute otitis media. Pediatrics 2013: 131: e398-405.

- Hoberman A, et al: Treatment of acute otitis media in children under 2 years of age. N Engl J Med 2011: 364: 105-115.

- Taylor S, et al: Impact of pneumococcal conjugate vaccination on otitis media. Clin Infect Dis 2012: 54: 1765-1773.

- Hekkinen T, et al: Effectiveness of intranasal live attenuated influenza vaccine against all-cause acute otitis media in children. Pediatric Infect Dis 2013: 32: 669-674.

- Lous J, et al: A systematic review of the effect of tympanostomy tubes in children with recurrent acute otitis media. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol 2012: 75: 1058-1061.

- Van den Aardeweg MT, et al: Adenoidectomy for otitis media in children. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2010 CD007810.

- Principi N, et al: Prevention of acute otitis media using currently available vaccines. Future Microbiol 2012: 7: 457-465.

- Azarpazhooh A, et al: Xylitol for preventing acute otitis media in children up to 12 years of age. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2011: CD007095.

- Thomas JP, et al: Acute otitis media, a structural approach. Dtsch Arztebl 2014: 111(8): 151-160.

- Forgle S, et al: Management of otitis media. Paediatr Child Health 2009: 14: 457-464.

- Guideline of the German Society of General Medicine (DEGAM) Earache. AWMF Register No. 053/009 Class S 3.

- Guideline Seromucotympanum of the German Society of Otorhinolaryngology. AVMF Register No. 017/004 Class S 1.

- Wollenberg B, et al: Practical therapy of ENT diseases. Stuttgart Schattauer 2008: 90.

- Rosenfeld R: Evidence-based otitis media: Canada. Hamilton ON 2003, 28.

HAUSARZT PRAXIS 2014; 9(9): 31-33