Ulcerative colitis is a chronic inflammatory bowel disease of unknown etiology. The clinic consists of bloody mucopurulent diarrhea with accompanying tenesmus and rarely fecal incontinence. The relapses are classified according to their spread and severity. Diagnosis requires a combination of clinical, laboratory, radiographic, endoscopic, and histologic findings. Therapeutic options include topical and systemic 5-ASA preparations. In the absence of efficacy, steroids, immunomodulatory drugs, or TNF-alpha antibodies may also be given. A severe episode should be treated as an inpatient. After remission has been achieved, permanent remission-maintaining therapy is indicated.

Ulcerative colitis (CU) is one of the chronic inflammatory bowel diseases. It is characterized by relapsing, chronic inflammation of the colonic mucosa. The exact cause is not known: It is a disorder of the immune system that occurs in certain genetic (more than 160 genetic variations are now known), dietary, and environmental constellations [1].

Spread

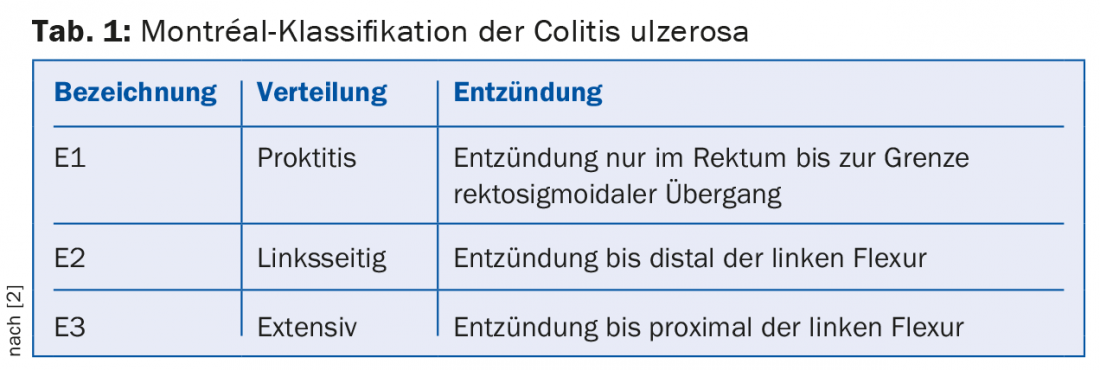

CU typically affects the colonic mucosa starting distally with continuous spread proximally. Special cases include involvement of the terminal ileum (so-called “backwash ileitis”), inflammation that is additionally isolated around the appendiceal outlet in left-sided CU (“cecal patch”), and the rectum-excluding variant. The ECCO guideline of 2012 recommends the classification of CU according to the Montréal classification according to the spread of inflammation [2]: If inflammation is limited to the rectum, it is referred to as ulcerative proctitis (E1); if it spreads to the left flexure, there is left-sided CU (E2); if disease activity is proximal to the left flexure, there is extensive CU (E3, pancreatitis). (Tab.1).

Extraintestinal manifestations occur in approximately 30% of patients in various organs (skin, eyes, joints, liver), sometimes parallel to the disease activity of CU, sometimes independent of it [3] (Table 2).

Epidemiology

The incidence in Western Europe is 11/100,000. It is higher in industrialized nations and at higher latitudes, and has been increasing over the last few decades. Diet, hygiene, and antibiotic use have been postulated as possible causes, with presumed resulting effects on the microbiome [4]. An Italian study in the primary care setting found a prevalence of 97/100,000 [5]. The median age of onset is 30-49 years. The initial manifestation of the disease occurs before the age of 25 in 25% of cases. Women and men contract the disease at about the same rate.

Forecast

In 80% of cases, the disease is relapsing; 50% initially have a mild relapse. In contrast, almost 20% of patients require initial hospitalization, half of which require initial colectomy despite intravenous steroid therapy. A younger age of onset is associated with increased relapses and severe activity. The risk of developing colorectal carcinoma is significantly increased in left-sided and extensive CU and is further increased by the concomitant presence of primary sclerosing cholangitis.

Risk factors

Familial exposure increases the risk of disease: for children of someone with CU, it is 2% [1]. Furthermore, a recent salmonella or campylobacter infection and a high standard of hygiene in childhood are risk factors. Low nicotine abuse and status post appendectomy for appendicitis are protective [2].

Clinic

In an acute episode, the patient suffers from bloody, mucous diarrhea, often also at night, with abdominal cramps (tenesmus) and urgency. Sometimes fecal incontinence also occurs. Depending on the severity of the episode, there may be anemia with poor performance, tachycardia, fever, malaise, and anorexia. If there are no clinical symptoms and the mucosa has healed endoscopically, the disease is referred to as deep remission. The severity of a relapse is classified into mild, moderate, and severe according to Truelove and Witts (Table 3) [6]. A severe episode is present when there are more than six bloody bowel movements per day and signs of systemic toxicity. Patients with severe relapses should be treated as inpatients.

Diagnostics

The diagnosis of CU results from a combination of history, clinic, laboratory chemistry tests including stool examinations, endoscopy findings, histology findings, and possibly radiology findings. Laboratory chemistry, inflammatory values (CRP, leukocytes) and thrombocytosis provide information about the inflammatory activity of CU. Hemoglobin levels may indicate anemia, and iron status may indicate iron deficiency or chronic inflammation. Elevated liver enzymes may indicate primary sclerosing cholangitis. An infectious cause of diarrhea is ruled out using stool samples for protozoa, helminths, and bacterial pathogens including Clostridium difficile. Irritable bowel syndrome can be largely ruled out initially by a pathologically elevated calprotectin in the stool [7]. Calprotectin, along with CRP, leukocytes, hemoglobin, and platelets, can also be used as a follow-up parameter for monitoring CU activity [2,8]. A CT abdomen may be useful to rule out complications such as toxic megacolon, perforation, transmigratory peritonitis, abscess, or stenosis with carcinoma in a severe episode or peritonitic abdomen and to differentiate diverticulitis.

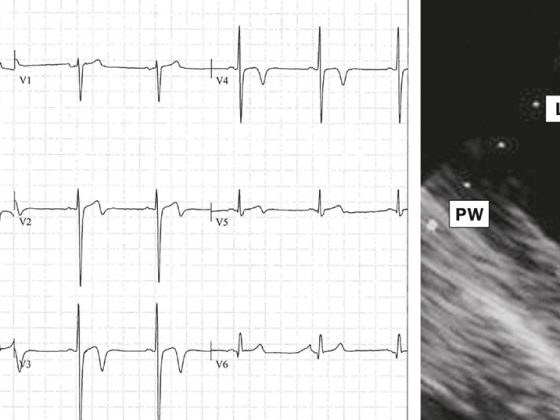

The most important component of diagnosis remains ileocolonoscopy with multiple biopsies. On the one hand, the diagnosis can often be made on the basis of typical histological changes, and on the other hand, infectious complications can be excluded (e.g. cytomegalovirus colitis). (Fig. 1). There is often a delay in diagnosis: In the Swiss IBD cohort, CU was diagnosed after a median of four months, with 75% of patients diagnosed within twelve months [9]. In Italy, the median time between symptom onset and diagnosis in the primary care setting was 14 months [5].

Therapy of the acute relapse

Therapy for remission induction is based on the anatomic spread and severity of the current episode of CU [10,11]:

- A mild to moderate episode of ulcerative proctitis (E1) is treated primarily with topical 5-amino salicylate (5-ASA) (suppositories 1 g/day). In the absence of response, topical budesonide is supplemented (rectal foam 2 mg/day). If inflammatory activity persists below this, oral therapy with 5-ASA (>2 g/day) or steroids should be started (Fig. 2).

- A mild to moderate episode of left-sided colitis (E2) is initially treated with a combination of oral and topical 5-ASA. Foam or enemas should be used instead of suppositories (2-4 g/d each) because, unlike suppositories, they reach the mucosa as far as the left flexure. Once-daily administration of 5-ASA is equivalent to several times daily administration. If ineffective, topical steroid therapy (e.g., budesonide foam) should be added first before oral steroid therapy. The initial dosage of oral therapy is 40 mg with weekly dose reductions of 5 mg (total duration approximately 8 weeks) (Fig. 2).

- Extensive CU (E3) should be initially treated with combined oral and topical 5-ASA for mild to moderate activity. Oral steroids are available as an escalation of therapy.

- A severe episode of CU is considered potentially life-threatening and should be treated as an inpatient. Early interdisciplinary evaluation together with the visceral surgeon is important. Initially, complications such as Clostridium difficile or cytomegalovirus colitis should be excluded. If intravenous administration of methylprednisolone (60 mg/day) shows no effect within approximately three days (response rate 67%), salvage therapy with ciclosporin (2 mg/kg i.v. for 8 days, response rate of 84% and colectomy rate of 9%) or a TNF-alpha antibody such as infliximab or adalimumab or colectomy should be discussed. Infliximab leads to a clinical response in 69.4% at eight weeks (clinical remission 34.7% at 54 weeks) [12]. Adalimumab resulted in a clinical response in 50.4% of patients after eight weeks (clinical remission 17.3% at 52 weeks) in the ULTRA-2 trial [13].

Remission-preserving therapy

After achieving remission, remission-maintaining therapy is always recommended. This is based on the spread, previous course, severity of the last episode and current medication. A 5-ASA preparation is permanently recommended as first-line therapy: topically at E1 (possibly E2) with a minimum dose of 3 g/week and systemically at E2 and E3 (minimum dose 1.2/d), with the combination topical and oral being most effective. At most, azathioprine (target dose 2-2.5 mg/kg body weight) or 6-mercaptopurine (target dose 1-1.5 mg/kg body weight) should be added for frequent relapse activity (>1× /year), early relapse, 5-ASA intolerance, or steroid-dependent course. Alternatively, therapy with a TNF-alpha antibody (infliximab, adalimumab, golimumab) or with tacrolimus would be possible.

Take-Home Messages

- Ulcerative colitis is divided into ulcerative proctitis, left-sided ulcerative colitis, and extensive ulcerative colitis based on anatomic spread.

- The extraintestinal manifestations occur partly in parallel with the inflammatory activity of the colon and partly independently of it.

- The classification of the severity of a relapse is based on Truelove and Witts’ criteria.

- A severe episode may require inpatient treatment.

- In remission, remission-maintaining therapy should always be performed.

Literature:

- Adams SM, et al: Ulcerative colitis. Am Fam Physician 2013; 87(10): 699-705.

- Dignass A, et al: Second European evidence-based Consensus on the diagnosis and management of ulcerative colitis: Definitions and diagnosis. J Crohns Colitis 2012; 6(10): 965-990.

- Vavricka S, et al: Frequency and risk factors for extraintestinal manifestations in the swiss inflammatory bowel disease cohort. Am J of Gastroenterology 2011; 106(1): 110-119.

- Talley NJ, et al: An evidence-based systematic review on medical therapies for inflammatory bowel disease. Am J Gastroenterol 2011; 106(suppl 1): 2-25.

- Tursi A, et al: Incidence and prevalence of inflammatory bowel disease in gastroenterology primary care setting. Eur J Intern Med 2014; 24(8): 852-856.

- Truelove SC, et al: Cortisone in ulcerative colitis; final report on a therapeutic trial. Br Med J 1955; 2: 1041-1048.

- Manz M, et al: Value of fecal calprotectin in the evaluation of patients with abdominal discomfort: an observational study. BMC Gastroenterol 2012; 12(5): 1471.

- Xiang JY, et al: Clinical value of fecal calprotectin in determining disease activity in ulcerative colitis. World J Gastroenterol 2008; 14(1): 53-57.

- Vavricka SR, et al: Systematic evaluation of risk factors for diagnostic delay in inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2012; 18(3): 496-505.

- Dignass A, et al: Second European evidence-based Consensus on the diagnosis and management of ulcerative colitis: Current Management. J Crohns Colitis 2012; 6(10): 991-1030.

- Manz M, et al: Treatment algorithm for moderate to severe ulcerative colitis. Swiss Med Wkly 2011; 141: w13235.

- Rutgeerts P, et al: Infliximab for Induction and Maintenance Therapy for Ulcerative Colitis. N Engl J Med 2005; 353(23): 2462-2476.

- Sandborn WJ, et al: Adalimumab induces and maintains clinical remission in patients with moderate to severe ulcerative colitis. Gastroenterology 2012; 142(2): 257-265.

HAUSARZT PRAXIS 2015; 10(4): 16-20