Treatment of vascular risk factors is effective dementia prevention. Dementia prevention is more effective than currently available therapies. Consistent treatment of vascular risk factors reduces the risk of various diseases – including dementia. Effects at the population level are already noticeable – dementia prevalence is increasing less than feared.

Vascular risk factors play a central role in the development and progression of dementia. Not only in vascular dementia, but also in Alzheimer-type dementia in particular, vascular risk factors may contribute to the onset of dementia earlier and more severely than in individuals without risk factors. Efficient therapies for the treatment of most forms of dementia are still hardly available, while at the same time the number of patients is steadily increasing due to demographic developments alone. And so the search for risk factors that can be influenced is of great interest not only medically, but also economically. This article is an abridged version of a detailed review on this topic published elsewhere [1].

Study situation

Autopsy studies show a substantial impact of vascular pathology on neurodegenerative dementias. However, the various papers do not provide a completely uniform picture, as the proportions of the various pathologies in the causes of dementia vary, sometimes considerably. Also, the proportion of dementia cases with vascular pathology in addition to neurodegenerative pathology varied among studies from 14 to 44%. Reasons for this could be based, on the one hand, on real differences between the populations studied, e.g. ethnic differences. On the other hand, such differences arise artificially, because different classifications of vascular dementia or vascular cognitive impairment are used, which allow a diagnosis just earlier or later. Cross-sectional/cohort studies show an association between vascular risk factors and dementia. Here, the classification into the different forms of dementia is based on clinical, not pathological criteria.

Risk factors

According to current knowledge, potentially modifiable risk factors for dementia include the vascular risk factors arterial hypertension, diabetes mellitus, hypercholesterolemia, smoking, and lack of physical activity. In addition, there are non-vascular but also influenceable risk factors (low educational level and depression) [2]. In addition, there are risk factors that cannot be influenced, such as age and apolipoprotein E genotype, and at most diet and social factors. There are contradictory study results regarding regular alcohol consumption: Light to moderate alcohol consumption is considered to have a protective effect, but excessive alcohol consumption is considered a risk factor for dementia in most studies [3].

The association between some potentially modifiable risk factors and dementia risk has been relatively well studied.

Diabetes mellitus: patients with long-standing diabetes have a significantly increased risk of cognitive decline and dementia. A systematic review on this topic also finds consistent results in a total of 15 prospective studies showing an association between diabetes and an increased risk of dementia.

Arterial hypertension: hypertension is associated with an increased risk of dementia. The greatest risk exists when blood pressure is already elevated in middle age. Interestingly, many studies find a certain U-shaped relationship: not only elevated blood pressure, but also very low blood pressure seems to lead to worse results in cognitive tests.

Dyslipidemia: The results of large epidemiological studies show a very likely association between hypercholesterolemia or atherosclerosis and the risk of developing dementia. In view of this fact, it is surprising at first glance that so far no convincing effects have been achieved with the treatment of this risk factor. Overall, the correlation appears to be weaker than for other vascular risk factors.

Smoking: Smoking is a major modifiable risk factor for the development of dementia, although a direct effect of smoking, namely cholinergic stimulation, might actually be expected to have positive outcomes on cognition. Although some cohort studies also provide conflicting results, the vast majority of available studies find a clear effect of smoking on the development of dementia, some of which is quantity-dependent. Intervention studies on the question of the influence of smoking cessation on the development of dementia are not available.

Exercise: lack of physical activity is also a recognized modifiable risk factor for developing dementia. The association between physical activity or exercise and dementia risk reduction is well established in numerous cohort studies and has been summarized elsewhere [4]. There are relatively few intervention studies, and according to the current state of knowledge, it is probably also important for this risk factor to adapt one’s lifestyle in middle age at the latest.

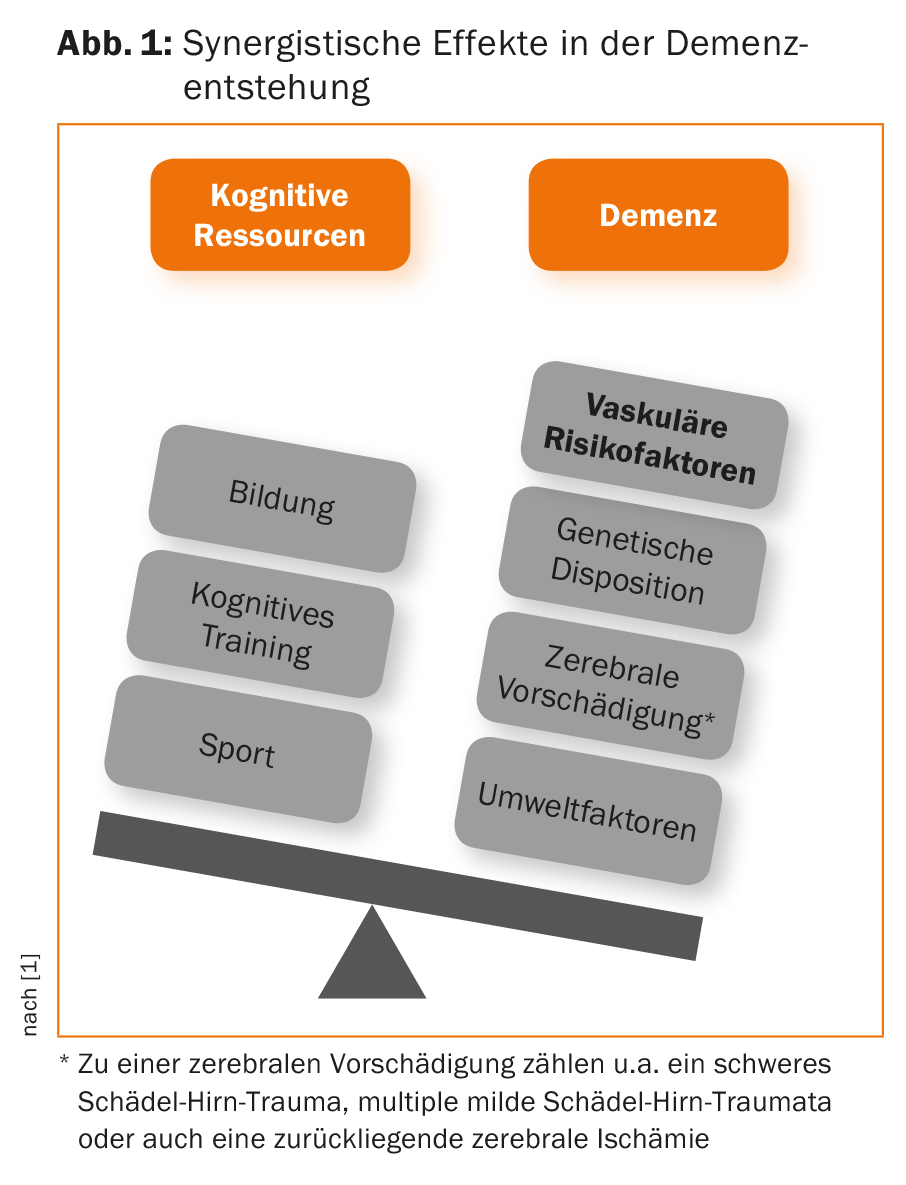

Synergistic effects

The coincidence of different risk factors can be called a synergistic effect in the development of dementia. Pathology alone is not sufficient to cause clinically relevant dementia. However, if another pathology is added, the threshold for clinically manifest dementia is crossed earlier (Fig.1). Of course, in addition to Alzheimer’s pathology and vascular changes, there may be other factors, such as nutritive aspects or a history of traumatic brain injury, all of which may act synergistically to lower the threshold for dementia development or advance the time of manifestation of dementia. A past stroke may also be an important factor, at least postponing the time of dementia onset [5].

Taking this concept of synergistic effects of dementia development as a basis, the importance of vascular risk factors in dementia development becomes clear. Alone, they have little potential to cause neurodegenerative dementia, but if they are present in combination, they can significantly increase the likelihood of developing dementia, especially in older age.

Therapeutic consequences

Data from intervention studies show that the concept of a multimodal approach with consistent treatment of all modifiable risk factors, if possible, can indeed be successful. In a recent meta-analysis, Wu et al. summarized five large European studies that looked at changes in the epidemiology of dementia over an observation period of up to 30 years [6]. As an example, the CFAS study from England predicted a dementia prevalence at the second survey in 2008-2011 of 8.3% after an initial survey in 1990-1993 [7]. However, a statistically significant declining prevalence of dementia of 6.5% was actually measured. Although all studies summarized in the meta-analysis were not explicitly designed to show effects by optimizing the treatment of vascular risk factors across the country, they were designed to show effects by optimizing the treatment of vascular risk factors across the country. Many other factors, such as improved access to education for broad segments of the later generation, may play a role as well. At the same time, however, there is evidence that over the periods compared, public awareness of the role of vascular risk factors for various diseases has improved, both in the general population and, for example, among primary care physicians, and that various cardiovascular diseases have therefore declined. Thus, the analysis of Wu et al. very likely be taken as an indication that modern treatment strategies of vascular risk factors are effective and have a preventive effect on the development of dementia.

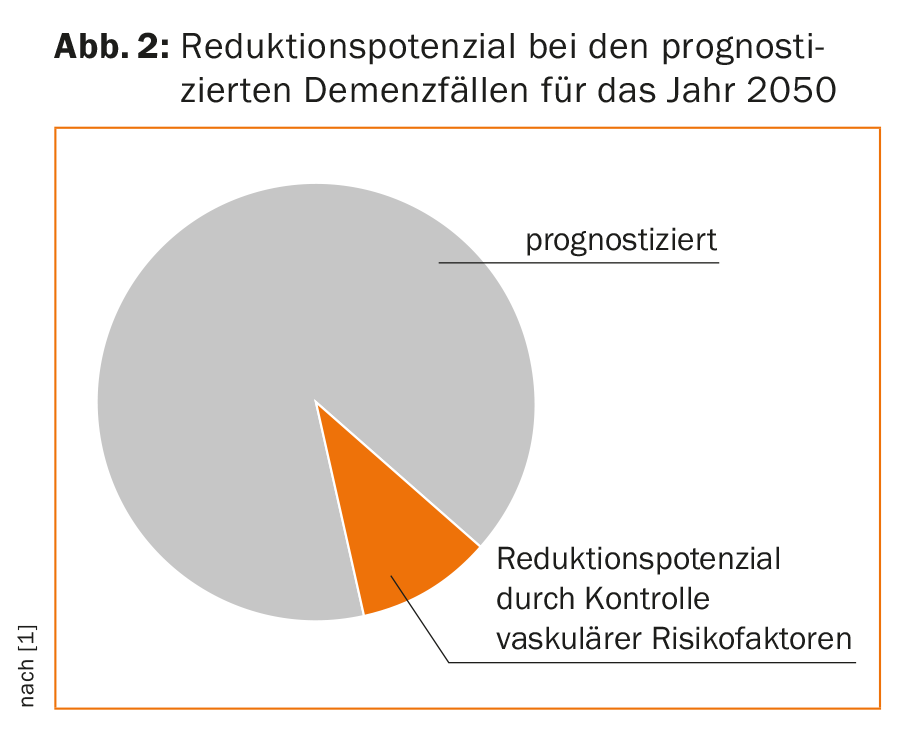

Detailed calculations of what reductions in dementia incidence and prevalence could be achieved with better control of vascular risk factors have been made by Barnes and Norton [2,8]. They calculate for individual risk factors their share of dementia cases in a population and conclude that with a 10% reduction in the prevalence of seven modifiable risk factors, a total of 1.1 million dementia cases could be prevented worldwide. In fact, a 25% reduction in the prevalence of these risk factors would result in a reduction of 3 million cases of dementia worldwide (Fig. 2).

Outlook

Modifiable risk factors are of particular importance in the prevention and possibly treatment of dementia today, as effective causal therapies are still lacking for virtually all dementias. If the prevalence of modifiable risk factors could be reduced at the population level, this would represent a substantial reduction in dementia prevalence.

Future approaches in the prevention of dementia aim at a multimodal strategy that includes modification of vascular risk factors as well as other known dementia-preventive interventions. For example, such an approach was pursued by the FINGER study published in 2015, which was able to demonstrate the potential of a multimodal approach consisting of treatment of vascular risk factors, nutritional counseling, physical training, and cognitive training in a randomized controlled approach prospectively over two years [9]. Such a strategy is also interesting because it targets modifiable risk factors that pose a risk not only for cognitive impairment but also for cardiovascular disease and tumor disease.

The reduction of dementia that can realistically be achieved with relatively simple measures would be of great importance not only medically, but also socially and economically. As long as there is no efficient therapy for dementia, we should at least make every effort to better exploit the already known possibilities to reduce dementia.

Literature:

- Felbecker A, et al: Role of vascular risk factors in the development and progression of Alzheimer’s dementia. Act Neurol 2016; 43(05): 309-317.

- Norton S, et al: Potential for primary prevention of Alzheimer’s disease: an analysis of population-based data. Lancet Neurol 2014; 13: 788-794.

- Di Marco LY, et al: Modifiable lifestyle factors in dementia: a systematic review of longitudinal observational cohort studies. J Alzheimers Dis 2014; 42: 119-135.

- Felbecker A, et al: Cognitive disorders. In: Reimers CD, eds. Prevention and therapy of neurological and mental disorders through sport. Munich: Elsevier; 2013: 443-474.

- Leys D, et al: Poststroke dementia. Lancet Neurol 2005; 4: 752-759.

- Wu YT, et al: Dementia in Western Europe: epidemiological evidence and implications for policy making. Lancet Neurol 2016 Jan; 15(1): 116-124.

- Matthews FE, et al: A two-decade comparison of prevalence of dementia in individuals aged 65 years and older from three geographical areas of England: results of the Cognitive Function and Ageing Study I and II. Lancet 2013; 382: 1405-1412.

- Barnes DE, et al: The projected effect of risk factor reduction on Alzheimer’s disease prevalence. Lancet Neurol 2011; 10: 819-828.

- Ngandu T, et al: A 2 year multidomain intervention of diet, exercise, cognitive training, and vascular risk monitoring versus control to prevent cognitive decline in at-risk elderly people (FINGER): a ranomised controlled trial. Lancet 2015; 385: 2255-2263.

InFo NEUROLOGY & PSYCHIATRY 2016; 4-6.