Actually, it is widely known that sport has a positive effect on our health and can also help with diseases. Nevertheless, this is still too little lectured at the decisive medical training institutions and insufficiently applied in practice. The purpose here is to present a publication that examines the impact of physical training on pathogenesis, symptoms, fitness, and quality of life in a clear and, most importantly, highly scientific manner.

In several respects, sports medicine is a complex specialty. Nevertheless, it is not oversimplified to consider it as the interface between medicine and sports, where both fields benefit from the “biological” characteristics of the other. Thus, classically, the sportsmen who benefit from the constant diagnostic and therapeutic advances in medicine. However, this also applies in the opposite direction: less well known, or at least less often taken into account in daily medical practice, is the fact that many patients can derive benefits from the extraordinarily diverse, sometimes unimagined effects of sport.

Today, we want to take a closer look at this lesser-known side, whereby a question of definition must first be clarified.

What is sport and why does it benefit us?

By sport we mean measured, controlled and reasonable physical activity and, of course, not the intense forms of training used in competitive sports. Even though there are already convincing reports about “High Intensity Interval Training” (HIIT) in the rehabilitation of heart patients! For example, a recent newspaper headlined, “High-intensity interval training even in heart failure – Who benefits from rapid strengthening for myocardium and circulation?” The article also emphasizes the important role of monitoring and calls for increased studies that examine the feasibility of HIIT in cardiac patients and discuss long-term effects.

In addition, there are numerous other articles from the medical press that headline the topic. Some claim: “Running improves eyesight”, “Sport against high pressure: 20 mmHg is easy”, “Endurance training is good for people with heart failure”. The others state, “Even if your lungs don’t really like it anymore, exercise is important” or “Physical activity strengthens your bones.”

Positive effects on cognitive and emotional factors are also reported: “Prevention of cognitive decline: more arguments in favor of physical activity”, “The effects of physical training on anxiety symptoms”, “Regular exercise makes new brain cells grow”, “Jogging for the gray matter”, to puns like “Stronger, healthier, smarter: the healing power of sport”.

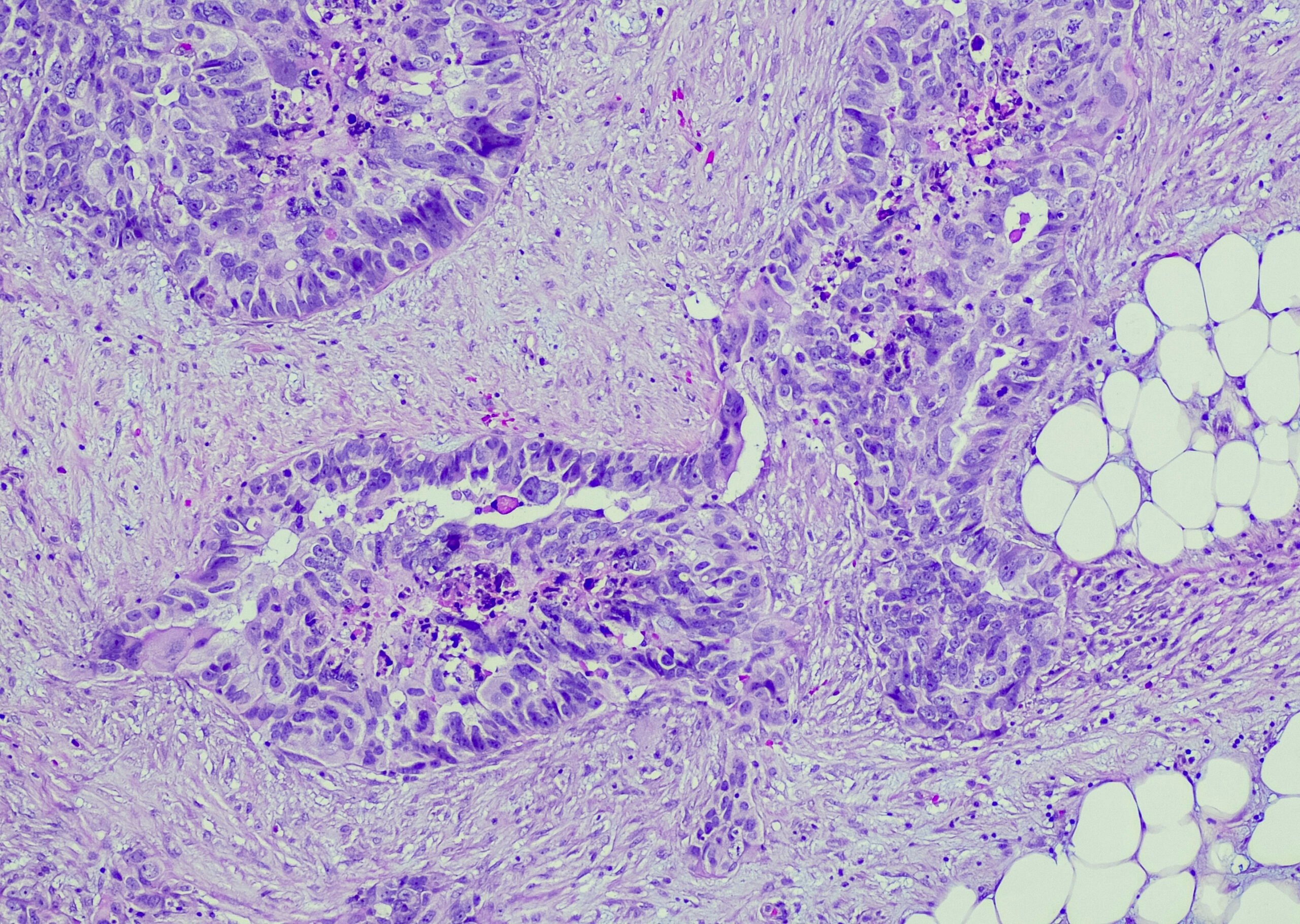

Almost all diseases seem to be positively influenceable with controlled sport: “Physical activity is one of the main therapies for type 2 diabetes,” “Physical activity reduces mortality in prostate cancer,” “Powers against fatigue in cancer patients,” “In psoriasis, intense physical activity is shown to be effective,” and “In Parkinson’s disease, mild exercise improves walking ability.”

In the same way, people speak of positive effects on sexual life (“Squats maintain erection”) and even see sport as a life-prolonging measure (“Fitness training: just 15 minutes a day increases life expectancy”).

Is there any evidence?

Even though the majority of these spectacular statements are based on serious scientific research, probably not all of them have been reproduced and tested by other research groups.

This is different in the special issue 1 of the Scandinavian Journal of Medicine&Science in Sports (Vol 16, February 2006), which is worth reading. In this excellent work, authors B.K. Pedersen and B. Saltin meticulously examined the evidence for prescribing physical activity as a therapy for chronic diseases in the literature and compiled the scientific background, rational basis for exercise, how to exercise, and practical advice on how to exercise in 18 different pathologies. Metabolic diseases such as insulin resistance, type 2 diabetes, type 1 diabetes, dyslipidemias and obesity, cardiovascular diseases such as hypertension, coronary heart disease, chronic heart failure and intermittent claudication, pulmonary diseases such as asthma and the COPD were scrutinized, but also problems of the musculoskeletal system such as arthrosis, rheumatoid arthritis, osteoporosis and even fibromyalgia and “chronic fatigue syndrome” were considered. The effect of exercise on cancer and depression was also analyzed.

For each disease, it is tabulated very clearly how strong the effect evidence of physical activity on the pathogenesis, on the symptoms typical of the disease, on the fitness achieved and on the quality of life is ultimately.

Hypertension, COPD, Asthma

For example, according to this article, exercise consistently shows strong evidence of effect on pathogenesis, symptoms, fitness, and quality of life in hypertension. The same applies to the disease COPD with the exception of pathogenesis: Here, there is no evidence at all so far that exercise has a positive effect.

This is also not confirmed for asthma. However, training here has limited evidence on symptoms, moderate evidence on quality of life, and strong evidence on fitness.

Sport is the best medicine

It should be emphasized again: This seemingly optimistic view of the high efficacy of physical activity is based on very strong scientific evidence, and actually one must rather marvel that these results are not more clearly pontificated and, above all, not more frequently applied in everyday practice. On the basis of certain works and for certain forms of disease, it has even been shown that exercise is more efficient than conventional therapy! Without talking about price and side effects.

Five years after publication, it may be argued that the evidence has, if anything, become even better, and this argues for further indications, such as those from the neuro-cognitive domain.

It is of great importance that in the near future the art of prescribing physical activity in medicine finds the place it deserves: “If exercise could be packed into a pill, it would be the single most widely prescribed and beneficial medicine in the nation. If only, doctors were to be aware of this fact”! We will come back to that.

HAUSARZT PRAXIS 2014; 9(2): 5-6