Sleep deprivation has been a common chronotherapeutic treatment option for depressive disorders for several decades. Sleep deprivation treatment is fast and well effective, easy to perform, non-invasive, cost-effective, and suitable for outpatient and inpatient depression treatment. Sleep deprivation leads to functional dissociation of the anterior cingulate from the resting network in the brain, as well as increased recruitment of the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex. Guideline-based therapy includes sleep deprivation as a complementary element for rapid response and augmentation of existing treatment. Sleep deprivation should not be performed in patients with a history of seizures or delusional depression.

There is a close relationship between affectivity and chronobiological rhythms. The sleep-wake cycle plays a special role in this respect: changes in sleep architecture and affect, whether toward the depressive or the manic pole, are mutually dependent. About 60-80% of patients with depressive disorder also suffer from insomniac symptoms. Often, sleep disturbances – especially early morning awakenings – immediately precede a depressive episode. Thus, at first glance, it seems paradoxical that restricting sleep can lead to clinically relevant symptom relief in already manifest depression. Sleep deprivation treatment, or awake therapy, is included in the group of chronotherapeutics. Environmental conditions are changed in such a way that patients’ biorhythms are specifically influenced (e.g. sleep deprivation, sleep phase shifting, light therapy, dark therapy). Over 60 studies have shown that 50-80% of all depressed patients benefit significantly from sleep deprivation. Especially in complicated treatment conditions such as bipolar depression, which is associated with low response to antidepressant medication, an antidepressant effect can be produced in over half of patients [1]. The effect strength is comparable to that of standard antidepressants, with better tolerability. A particularly important characteristic is that the same antidepressant effect, which is achieved with antidepressant medication only after four to six weeks, already occurs within 24 – 48 hours. Sleep deprivation and the as yet little established treatment with ketamine infusions are thus the only two available antidepressant therapy strategies with immediate onset of action [2].

A disadvantage of the treatment is the only short duration of the effect: Thus, more than 80% of patients relapse after only one night of sleep (the so-called recovery night) [3], certain patients already after short “naps” or short sleep episodes during the day after sleep deprivation. Nevertheless, there are studies that showed a sustained response after total sleep deprivation in 5-10% of the bipolar depressed patients studied. In recent years, various strategies have been developed to produce sustained remission (e.g., combinations with lithium, antidepressants, and light therapy). The strong and immediate, but only short-lasting antidepressant effect also makes sleep deprivation a preferred experimental method in depression research, since a neurobiological mechanism is obviously triggered here that decides in the form of a “switch” on the system state “depressive” or “non-depressive”. After initially studying mainly the effects of sleep deprivation on electrophysiological homeostatic regulation and neurotransmission, which showed an increase in serotonergic, noradrenergic, and dopaminergic tone, more recent studies have used mainly functional cerebral imaging.

Changes in brain connectivity after sleep deprivation.

Early positron emission tomography (PET) studies demonstrated that certain depressed patients had metabolic hyperactivity in the anterior cingulate cortex (ACC) and hypoactivity in the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC). Opposite normalization of these changes correlated with alleviation of depression symptoms. New research methods, such as analysis of brain network connectivity using functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI), have led to further understanding of the pathophysiology of depressive syndromes. Thus, an area in the prefrontal cortex known as the dorsal nexus has been identified to exhibit marked hyperconnectivity to various brain networks in depressed patients [4]. This area may potentially serve as a target structure or biomarker for research into antidepressant therapies.

A study by our own group now showed that sleep deprivation in healthy subjects leads to functional dissociation of the ACC from the resting network, with concomitant enhanced recruitment of areas of the DLPFC via the dorsal nexus. Further studies are needed to determine whether depressed patients with pathological overactivation of the ACC with concomitant underactivity of the DLPFC – as known from previous studies – specifically benefit from sleep deprivation intervention correcting this pattern [5].

Practice of sleep deprivation in depression treatment.

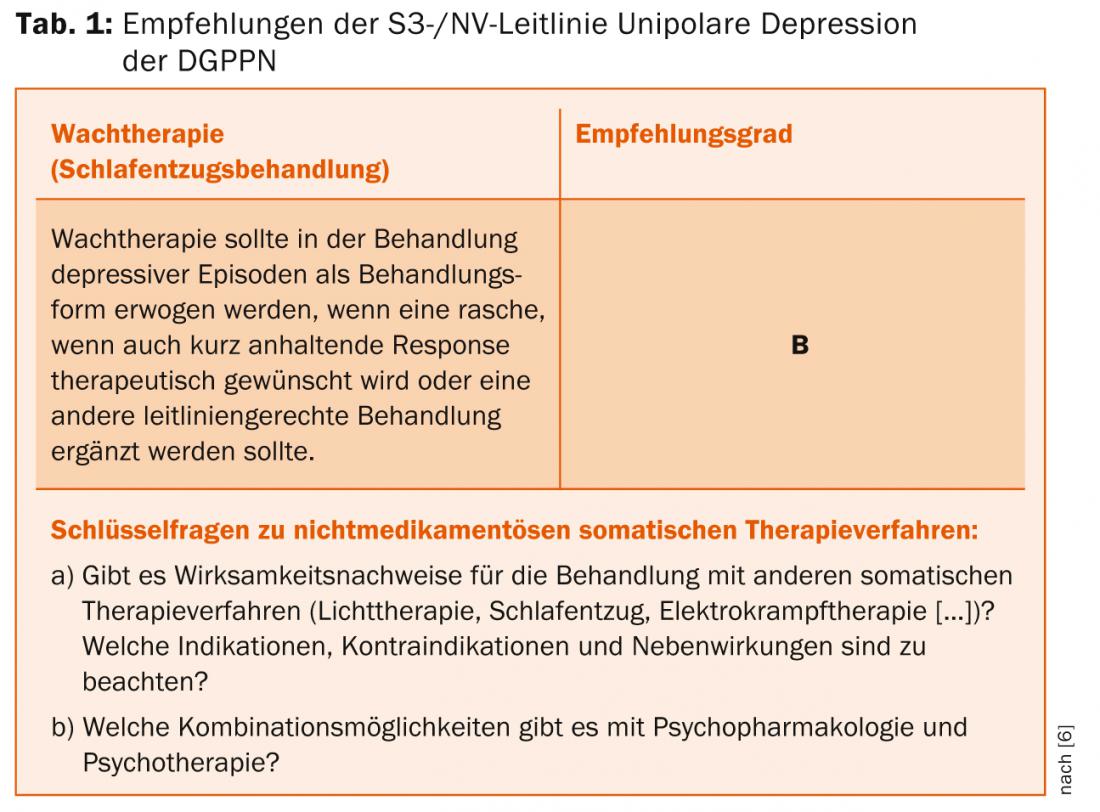

Despite the good scientific evidence on the effectiveness and safety of sleep deprivation treatment, it has not yet received adequate attention, especially in primary care. In the S3/National Health Care Guideline of the German Society for Psychiatry, Psychotherapy, Psychosomatics and Neurology (DGPPN), it is seen primarily in the context of the multimodal offer of psychiatric-psychotherapeutic wards. The inpatient setting is advantageous in that staying awake is facilitated by grouping sleep-deprived patients and monitoring by nursing staff.

However, the ease of use, non-invasiveness as well as cost efficiency make them attractive for outpatient use as well. According to the S3 guideline, sleep deprivation should be used as an add-on measure to an existing treatment, especially if a rapid response is to be achieved or an insufficient therapy is to be augmented (Tab. 1) [6].

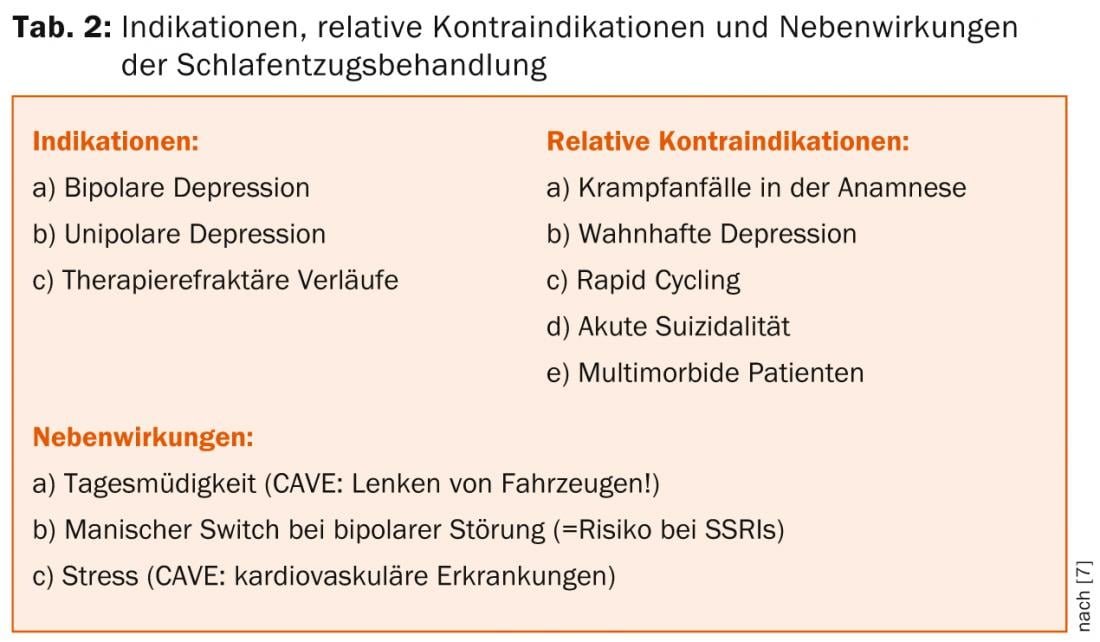

Indications include both unipolar and bipolar depression, especially in treatment-refractory courses. In this context, bipolar patients seem to benefit even better than unipolar ones, so that some authors see the primary indication for sleep deprivation treatment in this group of patients [7]. Clinical predictors of a response to sleep deprivation include mood swings during the day and the presence of a somatic syndrome (“melancholic depression”).

Because sleep deprivation leads to a decrease in seizure threshold, patients with a history of seizures should not be treated in this manner or should be treated only with intensive continuous monitoring. The same is true for patients with delusional depression, acute suicidality, and multimorbidity. Obviously, the main side effect is increased daytime sleepiness, which is why patients should not drive vehicles during periods of wakefulness. In addition, manic switches have been described in bipolar patients, but the risk does not exceed that of SSRIs. Therefore, special care should be taken in patients with rapid cycling. Because of the physical stress that sleep deprivation induces, special attention should also be paid to the presence of cardiovascular disease (Table 2).

Practically, two forms of sleep deprivation treatment are used:

- In partial sleep deprivation , the patient goes to sleep around 10:00 p.m., is awakened at 1:00 (or 3:00) a.m. the same night, and then goes back to regular sleep the following evening.

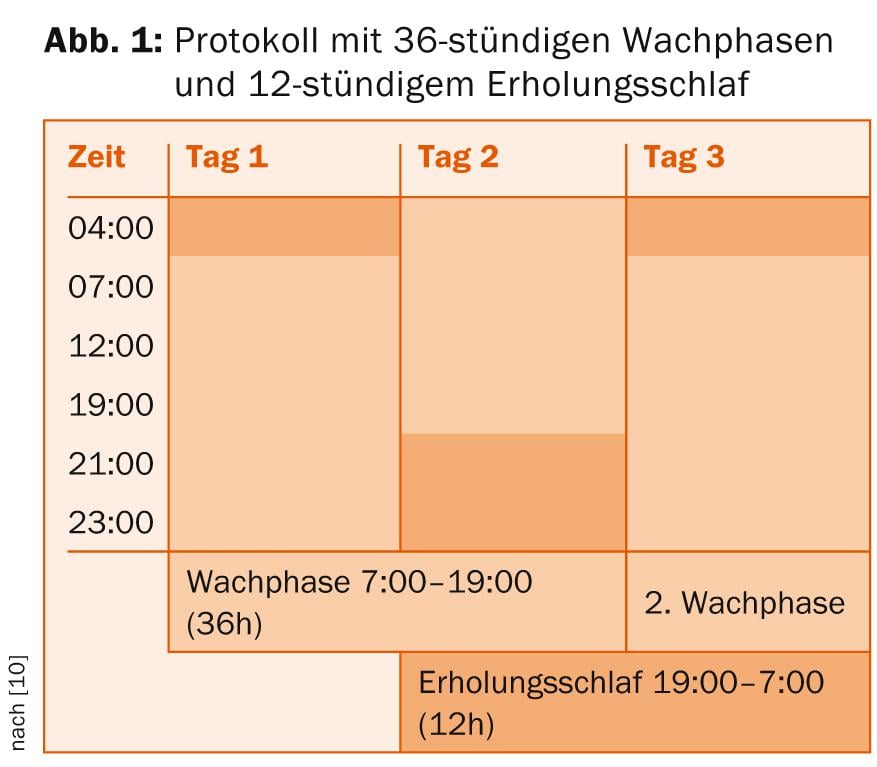

- In total sleep deprivation , the patient gets up at 7:00 AM the first day and goes through a wakefulness period of 36 hours until 7:00 PM the following day. This is followed by a twelve-hour recovery sleep until 7:00 a.m. the next day, after which a new cycle can begin (Fig. 1).

Evidence-based is the implementation of three periods of total sleep deprivation within one week. Existing medication should be continued in any case, but adjustments should be made to sedating medications if necessary so as not to make staying awake unnecessarily difficult. Another way of enhancing and possibly prolonging the antidepressant effect of sleep deprivation is to use combinations with antidepressants and lithium (according to the S3 guideline, also pindolol and thyroid hormones). However, sleep deprivation treatment can be performed without additional existing medication [8]. A protocol in which light therapy (10,000 lux for at least 30 minutes) is additionally applied during the waking phases and in the morning after recovery sleep seems to be particularly promising [9].

The effectiveness of sleep deprivation treatment has been demonstrated in numerous international studies involving thousands of depressed patients. A rational and scientifically based combination with other chronotherapeutic interventions such as light therapy improves the outcome, which is comparable to that of pharmacological treatment, with a significantly faster onset of action and fewer undesirable side effects. A manual developed in recent years also facilitates the implementation of sleep deprivation treatment in outpatient and inpatient settings [10].

The use of sleep deprivation in medical research has provided fascinating insights into the connections between affectivity and chronobiology. Due to the growing evidence on the effectiveness and safety of sleep deprivation treatment and the relevance of its biomechanisms, it is increasingly considered by more clinicians and researchers as a first-line treatment for affective disorders [7].

Literature:

- Wirz-Justice A, Terman M: Handb Clin Neurol 2012; 106: 697-713.

- Bunney BG, Bunney WE: Biol Psychiatry 2013; 73(12): 1164-1171.

- Hemmeter UM, Hemmeter-Spernal J, Krieg JC: Expert Rev Neurother 2010; 10(7): 1101-1115.

- Sheline YI, et al: Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2010; 107(24): 11020-11025.

- Bosch OG, et al: Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2013; 110(48): 19597-19602.

- DGPPN, et al.: 2010, Berlin, Heidelberg, New York: Springer-Verlag GmbH.

- Benedetti F, Colombo C: Neuropsychobiology 2011; 64(3): 141-151.

- Bauer M, et al: World J Biol Psychiatry 2013; 14(5): 334-385.

- Dallaspezia S, Benedetti F: Expert Rev Neurother 2011; 11(7): 961-970.

- Wirz-Justice A, Benedetti F, Terman M: 2009, Basel, Switzerland: Karger.

InFo NEUROLOGY & PSYCHIATRY 2014; 12(2): 16-18.