Several studies show that vulnerability to symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD/PTSD) is increased in descendants of trauma survivors. Psychobiological mechanisms involve the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenocortical axis, among others. The current article briefly summarizes the relevant findings and conclusions.

In animal and human experiments, an increased vulnerability to stress-related disorders and low cortisol levels as a biological correlate (typical finding in PTSD) could be demonstrated – both in those directly affected by traumatic experiences and in their children. However, it has also been found that these stress-related changes are reversible depending on living conditions. Experts recommend that trauma victims inform their family members about the trauma they have experienced so that symptoms can be recognized and treated early.

Unexplained nightmares and frightfulness

Anna doesn’t know what to do: her 16-year-old daughter has been waking up in the early hours of the morning with a loud scream for half a year. The teenager lies in bed drenched in sweat and tells her mother about diffuse fears and dreams; about dark, closed rooms from which she cannot find her way out. The girl has been reacting jumpy to loud noises for a long time and shows difficulties in contact with strangers. Under normal circumstances, one would suspect there were difficulties in the family or at school. The doctor consulted diagnoses symptoms that indicate post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). People with PTSD relive feelings, also known as “flashbacks,” often for years – even for life after the traumatic event if untreated. These disorders are observed after accidents, war experiences or other dramatic events. Described are anxiety, depression, jumpiness, and nightmare-like symptoms like Anna’s daughter. However, the teenager had not experienced any traumatic events. Born in a New York City hospital on December 13, 2001, the child lived in intact family circumstances with her parents and two healthy siblings. How can Anna’s daughter still develop PTSD symptoms?

She has spent a normal life, but her mother has experienced – and survived – terrible things: the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001 in New York. Six months pregnant, Anna was preparing a conference for her boss in the World Trade Center office early in the morning when the first hijacked plane slammed into the North Tower 50 floors above her at 8:46. She and her office colleagues were able to escape before the tower collapsed. About 3000 did not make it, dying in the flames or in the collapsing buildings. “The sounds of bodies hitting the ground haunt me to this day,” Anna told the doctor caring for her daughter; she was referring to the people who, in desperation, jumped out of windows and hit the asphalt. She never talked about the drama with her daughter – she didn’t want to burden her with it. How can this suffer from PTSD even though she was not born at the time?

This fictional story has been shown to be so, or similar, in numerous cases described both scientifically and journalistically after the dramatic events of 9/11 [1–3].

Are traumas genetically transmitted to offspring?

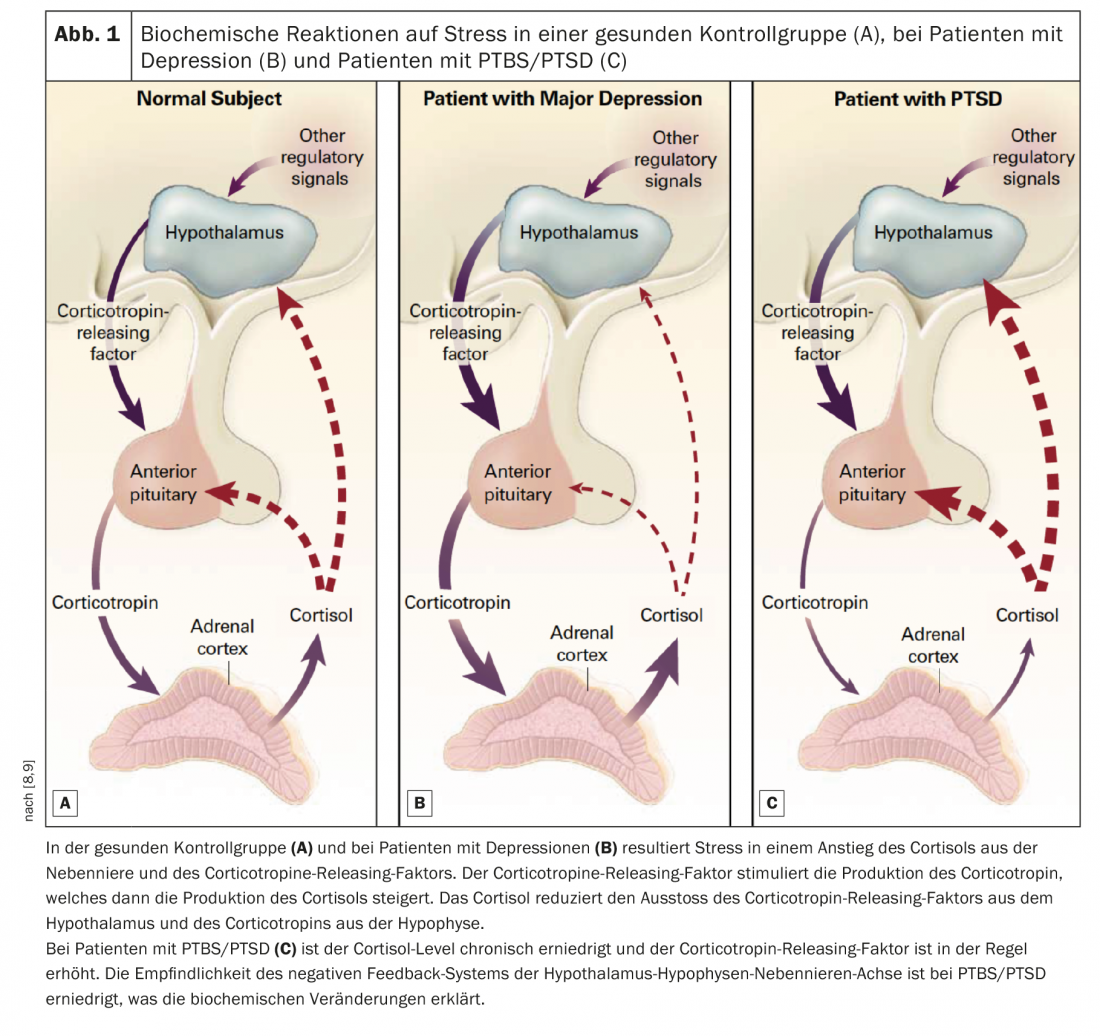

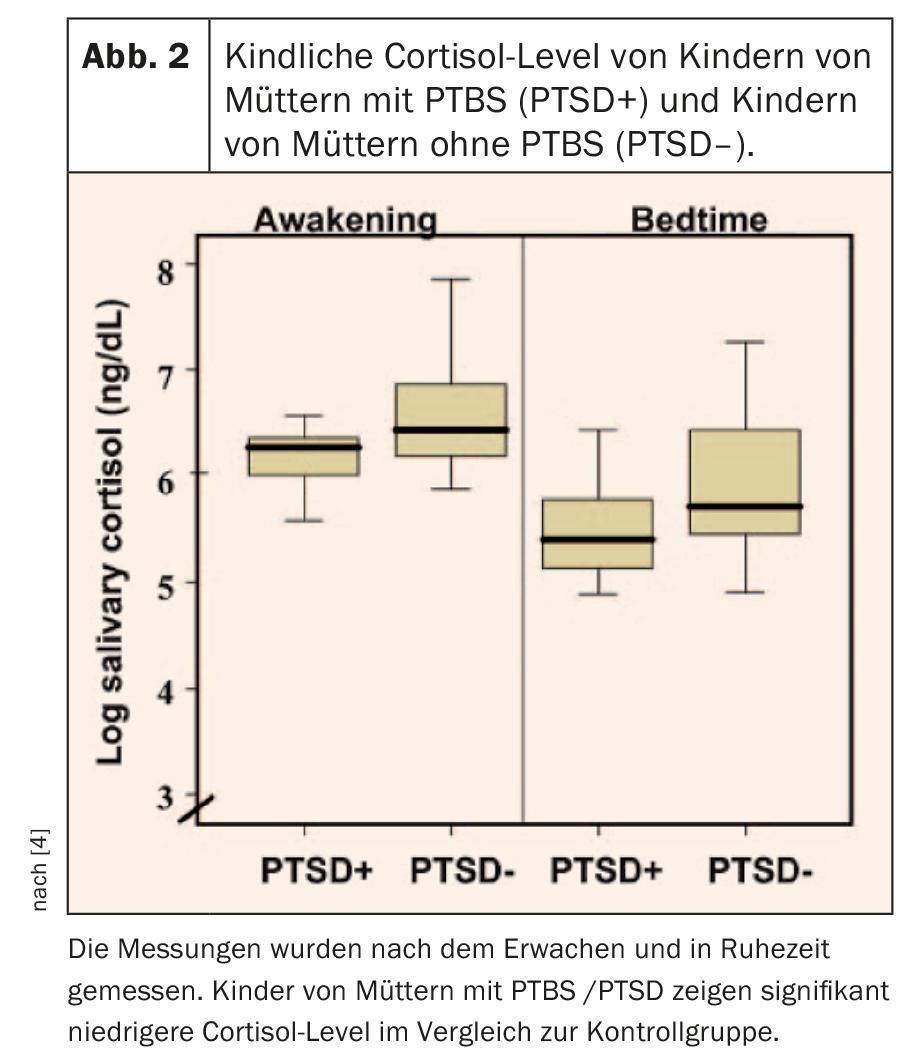

Rachel Yehuda, a professor of psychiatry at Mount Sinai University in New York, has been researching PTSD for years. She demonstrated that victims of trauma had typical decreases in an endogenous hormone, cortisol [4]. Decreased cortisol levels have been described in sequelae of chronic trauma and are complexly controlled by genes; the exact mechanisms are the subject of numerous investigations (Fig. 1). These changes have been observed in numerous other groups, including survivors of the World Trade Center attacks and Holocaust survivors [5]. Both groups had similar symptoms of PTSD and decreased cortisol levels [1].

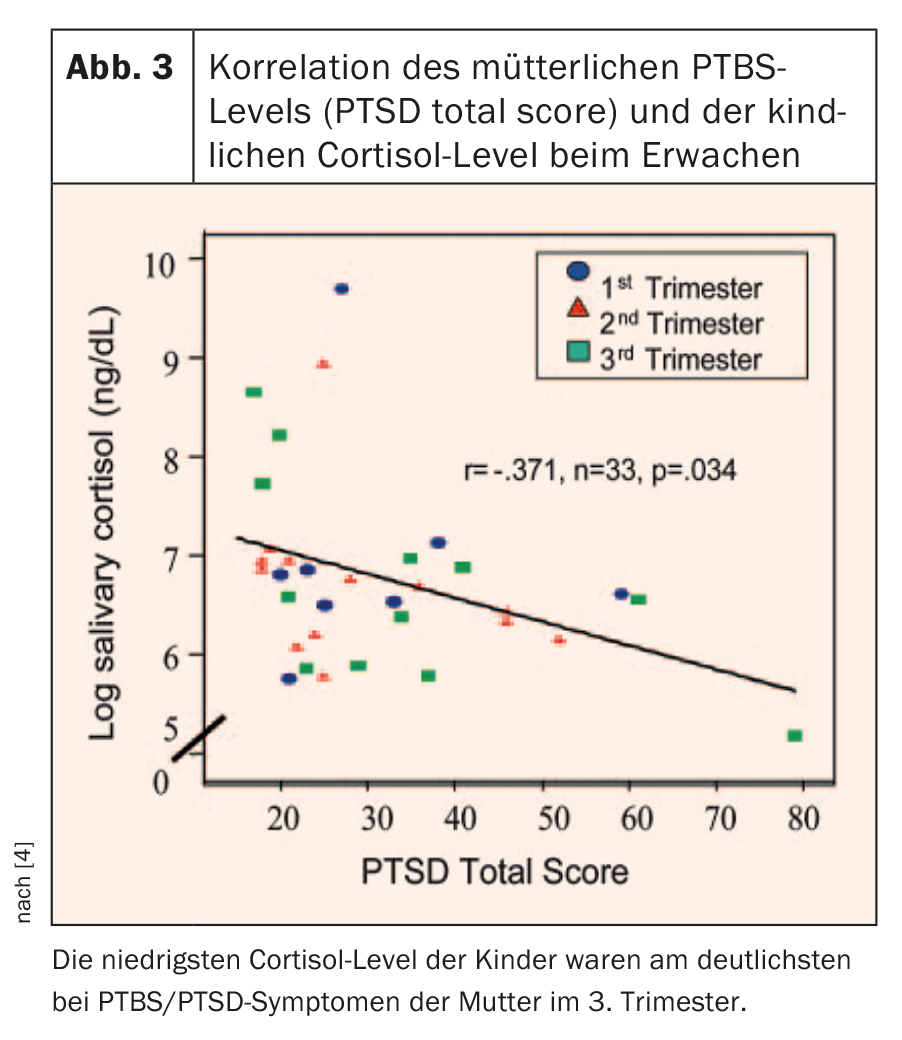

The exciting and shocking thing about the studies is: not only the victims showed these changes, but also their offspring. Yehuda was able to demonstrate that traumatized parents with PTSD symptoms gave birth to children with similar symptoms; they carried clinical and psychological symptoms of trauma that they themselves had not experienced (Fig. 2, Fig. 3) [2].

Up to four generations in our psyche

Animal studies seem to confirm this theory. Researchers repeatedly stressed male mice by separating them from their mothers. These mice responded with signs of depression. The scientists allowed these animals to reproduce – their offspring showed similar symptoms to their parents. These changes could be followed into the fourth generation, although they no longer had to experience trauma. It has been shown on several occasions that traumatized laboratory animals exhibited changes in their genetic material that were passed on over several generations [6].

But there is hope: the same research teams were able to demonstrate, at least in animal experiments, that stress-induced changes are reversible under better living conditions, both in the affected animals and their offspring [7].

Open questions

What can be learned from these studies? From the evidence that traumatic experiences can be transmitted to descendants? Researchers call this process “transgenerational epigenetic inheritance.” How and where the genetic changes take place has not yet been conclusively clarified. Until solid evidence is available, psychiatrists recommend that people with traumatic experiences inform their children about the nature and extent of the trauma. This makes it possible to examine, identify earlier, and treat offspring problems in a new context.

Interestingly, the Bible already seems to describe modern scientific knowledge. Doesn’t the Book of Genesis already tell us that the guilt of the fathers can be followed up to the fourth generation? This has nothing to do with science, it is probably personal experience of the Bible authors. Until we know more about transgenerational transmissions of trauma, victims should receive prompt and professional help. The most important thing is that their children and grandchildren are our future generations and should not be forgotten.

Literature:

- Brand SR, et al: The effect of maternal PTSD following in utero trauma exposure on behavior and temperament in the 9-month-old infant. Ann N Y Acad Sci 2006; 1071: 454-458.

- Yehuda R, Bierer LM: Transgenerational transmission of cortisol and PTSD risk. Prog Brain Res 2008; 167: 121-135.

- Uchida M, et al: Parental posttraumatic stress and child behavioral problems in world trade center responders. Am J Ind Med 2018; 61(6): 504-514.

- Yehuda R, et al: Transgenerational effects of posttraumatic stress disorder in babies of mothers exposed to the World Trade Center attacks during pregnancy. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2005; 90(7): 4115-4118.

- Rakoff V: A long-term effect of the concentration camp experience. Viewpoints 1966; 1: 17-22.

- van Steenwyk G, et al: Transgenerational inheritance of behavioral and metabolic effects of paternal exposure to traumatic stress in early postnatal life: evidence in the4th generation. Environ Epigenet 2018 Oct 16; 4(2). https://doi.org/10.1093/eep/dvy023

- Gapp K, et al: Potential of Environmental Enrichment to Prevent Transgenerational Effects of Paternal Trauma. Neuropsychopharmacology 2016; 41(11): 2749-2758.

- Yehuda R: Post Traumatic Stress Disorder. N Engl J Med 2002; 346(2): 108-114.

- Anisman H, et al: Posttraumatic stress symptoms and salivary cortisol levels. Am J Psychiatry 2001; 158: 1509-1511.

InFo NEUROLOGY & PSYCHIATRY 2019; 17(1): 32-35.