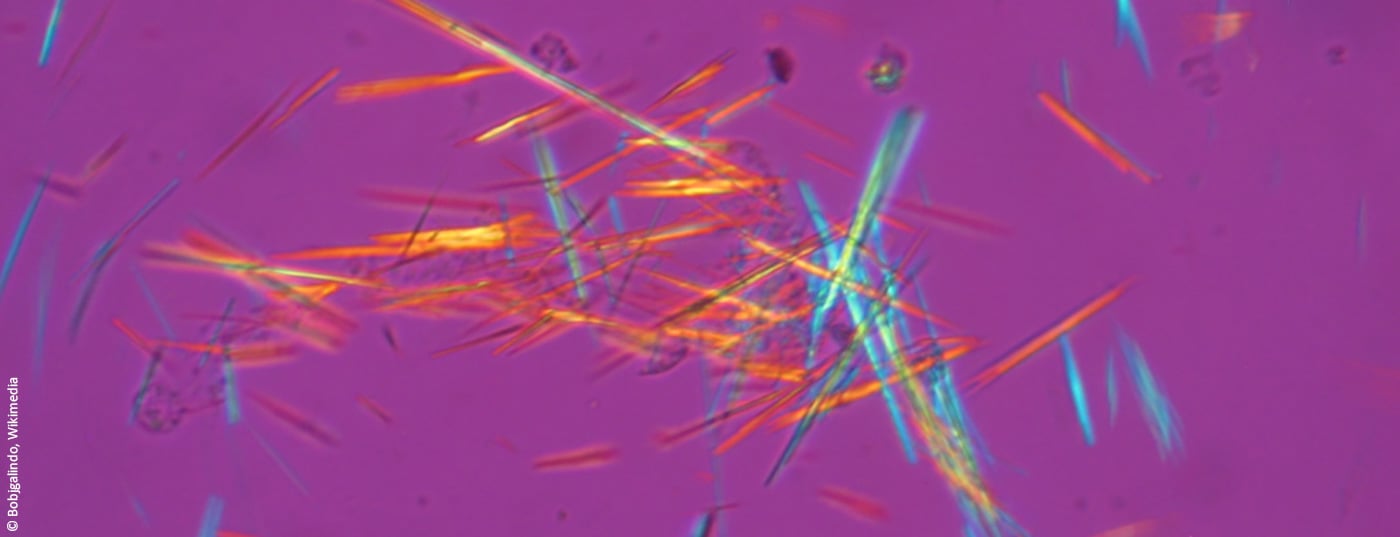

The diagnostic gold standard of a gout attack is the detection of urate crystals in the synovial fluid by polarized light microscopy. Anti-inflammatory and analgesic substances are used for acute treatment. However, long-term management of hyperuricemia is also important to prevent further gout flares and possible complications. In addition to dietary measures, various uric acid-lowering drugs are available for this purpose.

Gout is one of the most common inflammatory joint diseases. According to the European League Against Rheumatism (EULAR), the prevalence is around 1-2% in the adult Western population [1,2]. An acute gout attack is manifested by seizure-like, severe pain that occurs very suddenly and often at night, at least at the beginning of the disease. Symptoms may resemble those of classic arthritic complaints. However, although osteoarthritis, arthritis and gout all belong to the so-called rheumatic group, they are diseases with different causes [3]. Gout is a metabolic disease in which urate crystals accumulate intra- and periarticularly due to the kidney’s inability to excrete enough uric acid from purine metabolism in the urine.

Primary hyperuricemia: causal treatment possible

Nine out of ten patients suffer from primary hyperuricemia; much rarer are secondary causes, in which the gout symptoms are due to certain underlying diseases (e.g., renal insufficiency) or medications (e.g., diuretics) [3]. Hyperuricemia may be asymptomatic for a long period of time before acute arthritic symptoms become apparent as a result of a severe inflammatory local reaction with crystal phagocytosis [4]. The affected joint is extremely sensitive to touch, thickened and feels warm. Repeated gout flare-ups can lead to joint destruction and permanent painful damage. Therefore, not only the symptomatic treatment of an acute episode, but also the causal therapy of hyperuricemia is important. Risk factors for the development of gout include high-purine diet, obesity, hypertriglyceridemia, hypercholesterolemia, and diabetes, as well as hypertension and renal insufficiency. Treatment of these factors should be included in disease management.

Joint puncture and imaging to confirm diagnosis

A sudden onset of painful monoarthritis is a typical clinical feature of an acute gout attack. In addition to swelling and redness, severe pain and severe functional limitation of the affected joint are characteristic. In terms of anamnesis, an acute gout attack is often preceded by a sumptuous meal on the previous day or a purine-rich diet in general. To confirm the suspected diagnosis, joint puncture for the purpose of detecting uric acid crystals is recommended [5]. A determination of urate in the serum, on the other hand, is not useful in this phase, as the uric acid concentrations are then often reduced [5]. Patients with so-called “pseudogout” also have similar symptoms to those of gout. However, in pseudogout, calcium pyrophosphate crystals rather than uric acid crystals can be detected in the synovial fluid [6]. Another difference is that gout disease often first shows up in the metatarsophalangeal joint of the big toe or other small joints, whereas pseudogout shows up in large joints such as the knee. Sonographically, periarticular tophi and the double contour sign on the hyaline articular cartilage caused by uric acid deposition are findings of high specificity for the presence of gout [4]. Dual-energy computed tomography (CT) also has high specificity (80%) as well as high sensitivity (90%) [5]. By this method, uric acid deposits in tissues are visualized based on their absorption behavior [4]. In addition, an X-ray examination can be used to assess any damage already done to the bones.

Acute phase: inhibit inflammation and relieve pain

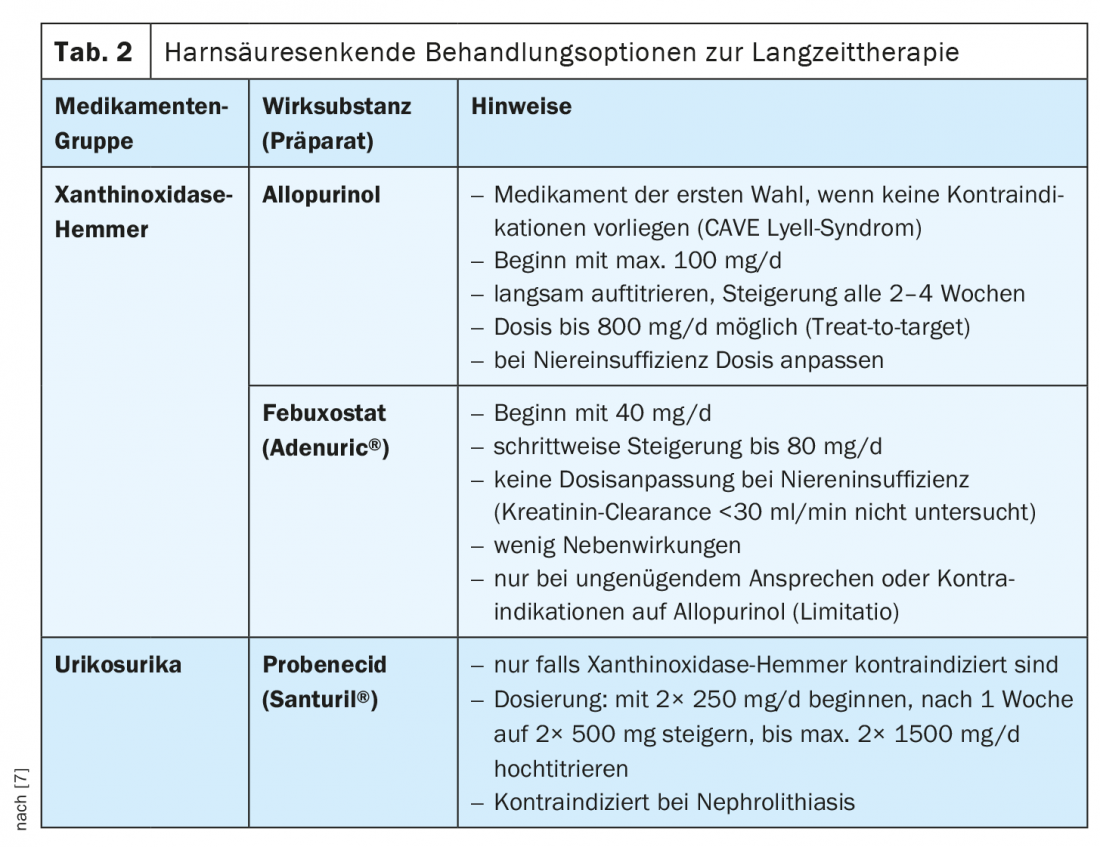

Treatment distinguishes between therapy of an acute gout attack and long-term disease management (Fig. 1) . First, patients must be educated about nutritional measures. If possible, purine-rich foods such as meat, fish or seafood should be avoided, as well as alcohol and drinks containing fructose. However, a change in diet alone is often not enough. Drug treatment of an acute gout flare-up focuses on anti-inflammation and pain relief. In general, it is important to treat a gout flare as early as possible to reduce the risk of permanent damage and improve the patient’s quality of life. The benefits and risks of treatment must be weighed up on an individual basis. According to current EULAR recommendations, in addition to non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and steroids, colchizines and the interleukin-1 inhibitor anakinra can also be used. The therapeutic options available in Switzerland are summarized in Table 1 (anakinra is not currently approved in Switzerland) [7]. Steroids should be dosed sufficiently high (per os 30-35 mg for 5 days, intraarticularly if necessary). Like NSAIDs and steroids, colchicine has an acute anti-inflammatory effect, but must never be overdosed due to toxic side effects [8]. Hepatic and renal insufficiency are contraindications to colchicine treatment, and possible interactions with other drugs (e.g., diltiazem, clarithromycin, ciclosporin, cholesterol-lowering agents) should be kept in mind [5]. If NSAIDs, colchicines, or steroids are not effective as the sole therapeutic measure, a combined use of these substances can be considered.

Long-term therapy with uric acid-lowering drugs

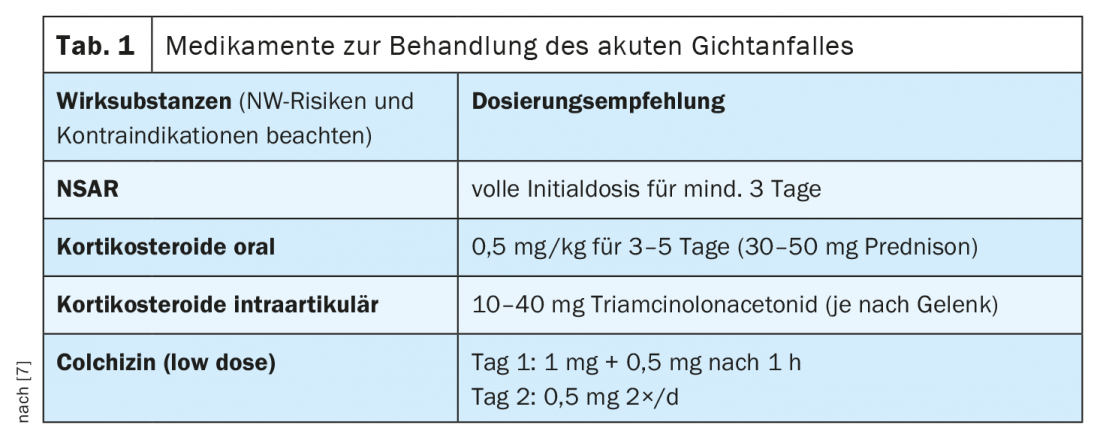

For long-term disease control, it is important to reduce the uric acid concentration to a value below 360 µmol/l or, in tophi, to below 300 µmol/l [5]. Consistent permanent uric acid lowering serves to prevent further gout attacks and thus to prevent structural damage [9]. A change in diet (avoiding purine-rich foods) is important, but often not sufficient. Recurrent gout attacks, manifest nephrolithiasis and gouty tophi, and chronic active gout are mentioned as criteria for the indication of drug-induced uric acid lowering [10]. In particular, if affected patients are under 40 years of age, uric acid levels are >480 µmol/l, tophi are present, and at least one comorbidity and >2 relapses have been documented, initiation of uric acid-lowering therapy is recommended after an acute relapse has resolved. Since this should be continued for years, the respective advantages and disadvantages must be weighed up individually. In Switzerland, uric acid-lowering therapy options include xanthoxidase inhibitors (allopurinol and febuxostat), pegloticase/rasburicase and, in special cases, uricosurics (Tab. 2) . Therapy should be started slowly after the episode has healed. The first choice is Allopurinol, it is recommended to increase the dose every 2-4 weeks, if uric acid target values are not reached, can be up-titrated, in renal insufficiency the dosage should be adjusted. CAVE Lyell syndrome: this is a serious allergic drug side effect that is potentially life-threatening (prevalence 0.7:1000, mortality rate 25%). The allergic reaction also known as toxic epidermal necrolysis is characterized by progressive blistering of the skin with consecutive epidermolysis. Patients with the allele HLA-B*5801 have an increased risk. Allopurinol is not recommended in patients of Asian or African descent [5]. If there is an inadequate response to allopurinol, or if contraindications exist, febuxostat may be used as an alternative. Initially, a dosage of 40 mg is recommended, subsequently slowly titrating up to 80 mg. Contraindications include severe hepatic or renal insufficiency (clearance <30 ml/min). Interactions are possible with azathioprine or rosiglitazones, among others. The only uricosuric drug currently approved in Switzerland is probenecid. however, the use of uricosurics is only indicated when xanthine oxidase inhibitors are not tolerated or are contraindicated. The recommended dosage is 250-1000 mg, 2×/day [5]. Probenecid enhances renal excretion of uric acid by inhibiting reabsorption of urate ions in the proximal tubule. Renal insufficiency is a contraindication. In exceptional cases (e.g., tumor patients), pegloticase (pegylated recombinant uricase) or the uricolytic rasburicase can be used as an alternative for uncontrollable gout. be used.

Literature:

- Zhang W, et al: Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases 2006; 65(10): 1312-1324.

- Richette P, et al: Ann Rheum Dis 2017; 76(1): 29-42.

- Gout, https://gelenk-klinik.de/gelenke/gicht.html, (last accessed Dec. 21, 2021).

- Forster A, Krebs A: Swiss Med Forum 2017;17(17): 387-390.

- Enderlin Steiger S: Gout – an update, Susanna Enderlin Steiger, MD, FomF 11/20/2021.

- Rheumaliga Schweiz, www.rheumaliga.ch/assets/doc/ZH_Dokumente/Broschueren-Merkblaetter/Gicht-und-Pseudogicht.pdf (last accessed 21.12.2021)

- Bürge S, Gross P: Gout under control, Rheumatology in Practice, Jan. 25, 2017, www.stgag.ch (last accessed Dec. 21, 2021).

- Kantonsspital Winterthur: Gout, www.ksw.ch/gesundheitsthemen/gicht-arthritis-urica (last accessed Dec. 21, 2021).

- Kiltz U, et al: Zeitschr Rheumatol 2016; 75(S2): 11-60.

- Crystal Arthropathy, www.sciencedirect.com/topics/clinicalkey/now/de/kristallarthropathie.html (last accessed Dec. 21, 2021).

- National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, www.cdc.gov/arthritis/basics/gout.htm, (last accessed Dec. 21, 2021).