The SARS-CoV-2 virus poses a particular challenge for hematologic patients. hazard. On the one hand, their immune system is often weakened by the disease and, on the other hand, numerous therapies additionally reduce the immune response. What is to be done when blood cancer and COVID-19 meet? And what is the importance of vaccination?

In light of the pandemic, not only is the care of hematology patients at risk, but another threat to them has emerged in the form of a potentially deadly virus. While COVID-19-related mortality in the inpatient sector is about 12.1% for non-oncology patients overall, it is 20.5% for oncology patients – a statistically significant difference. These figures are provided by the LeanEuropean Open Survey on SARS-CoV-2 infected patients (LEOSS ) registry. Even after intensive care treatment for the infection, the registry found that the mortality of cancer-affected patients is higher than that of patients without an oncologic diagnosis. Affected individuals with hematologic disease are at additional risk, as shown in a study published in Nature in August 2020 [1]. This proved what many already suspected at the time: COVID-19 mortality in hematological patients is particularly high. It is higher than that of all other oncological patients and comparable to that of immunosuppressed patients. In the first year of therapy, the risk of dying from SARS-CoV-2 virus is even increased by a factor of 2 compared to the general population. With regard to the underlying disease, lymphoma in particular seems to be a poor predictor of the course of SARS-CoV-2 infection [2]. These findings over the past two years give rise to a differentiated approach to COVID-19 disease in hematologic patients and underscore the importance of providing the best possible prophylaxis in this population-a challenge given the dynamic situation and young study landscape.

Which patients are particularly at risk?

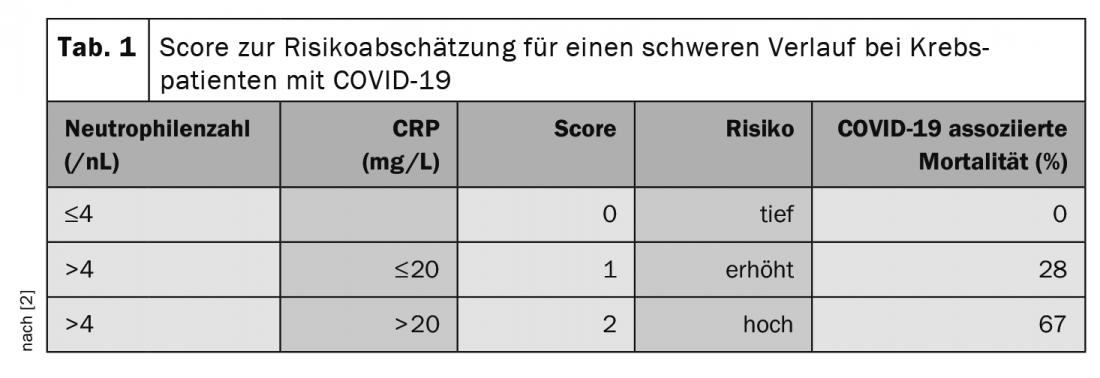

At the annual meeting of the German, Austrian and Swiss Societies of Hematology and Medical Oncology in October, Prof. Clemens Wendtner, MD, Chief of Medicine at München Klinik Schwabing and Scientific Secretary of the German CLL Study Group (DCLLSG), emphasized the importance of treatment for COVID-19-associated risk. In particular, patients under therapy with anti-CD20 antibodies such as Rituximab and under steroid treatment are at risk, whereby already >10 mg/d prednisone equivalent for >5 days are to be considered critical. Checkpoint inhibitors are also associated with increased lethality [2]. One study also sought factors to predict severe COVID-19 progression in tumor patients [2]. Here, the neutrophil count (>4.4/nL) and CRP level (>20 mg/L) before infection seem to be of prognostic value. The authors developed a score from this finding (Tab. 1).

Management of SARS-CoV-2 in hematology patients: Dancing with the devil

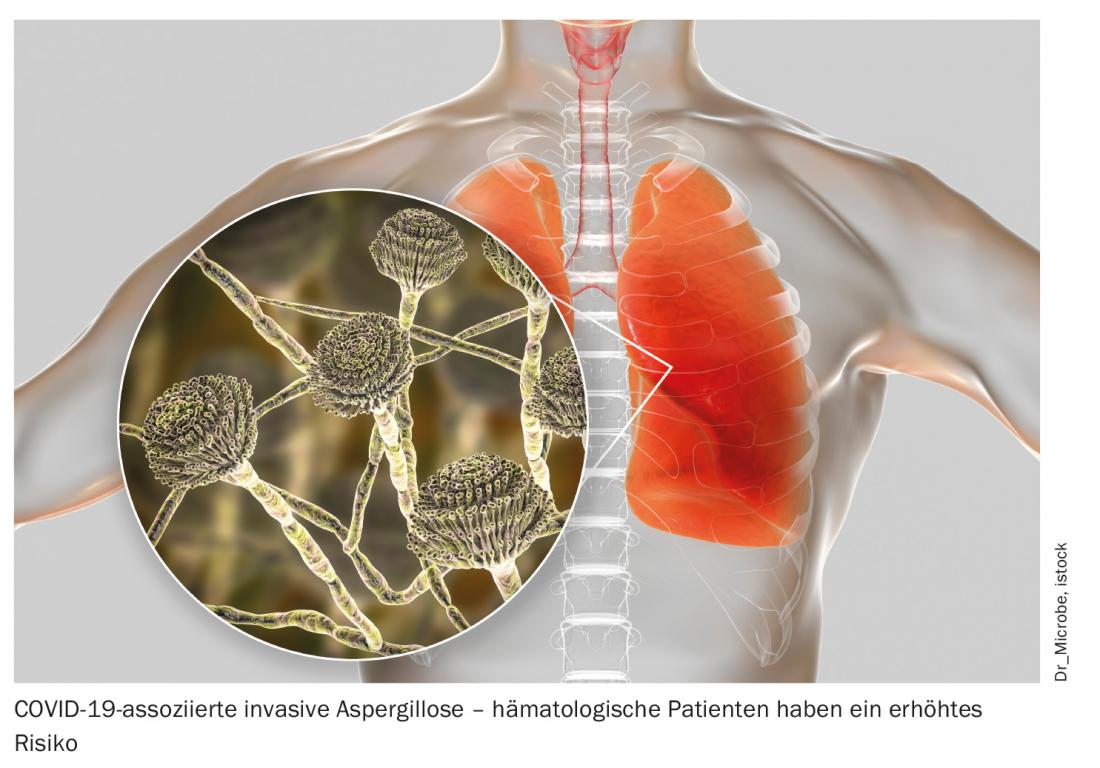

In addition to increased susceptibility to severe and fatal COVID-19 courses, prolonged viral shedding of up to 70 days after diagnosis is also found in those affected by hematologic malignancies. This poses a potential risk of infection to contacts, even if the patient is asymptomatic, and should not be overlooked in the treatment of such patients [3]. In addition to strict adherence to hygiene measures for the benefit of all involved, early treatment is particularly important. In this context, the best therapeutic approach remains unclear. According to the experts at the congress, the optimization of supportive measures in particular is an undisputed priority. This includes prophylactic anticoagulation in hospitalized patients, but also good antibiotic, antiviral, and antifungal prophylaxis and therapy of secondary infections. For example, consistent drug shielding results in a significantly lower incidence of COVID-19-associated pulmonary aspergillosis [4]. Also, intravenous immunoglobulins (IVIG) can and should be used in cases of proven secondary immunoglobulin deficiency. Whether any immunosuppression should be discontinued in the face of COVID-19 disease is currently unclear and must be decided on an individual basis. In general, treatment of this particularly vulnerable group of patients should be individualized and closely based on immunosuppression and antibody titers.

With regard to specific COVID-19 therapy, as in non-hematologic patients, the antiviral remdesivir, dexamethasone, and tocilizumab in particular are used. Increasingly, treatment using passive antibody therapy is also coming into focus. This plays an increasing role especially in seronegative patients – and these include immunosuppressed patients and those affected by hematological malignancies. Meanwhile, some studies exist on the combination of the agents casirivimab and imdevimab, also known as REGEN-COV. Alternatively, convalescent plasma can be used, although there are currently no positive studies in immunosuppressed patients. In any case, early treatment within 3-5 days of symptom onset is most promising. Use in high-risk patients as part of post-exposure prophylaxis – for example, after a nosocomial outbreak – is conceivable and is currently being investigated. In a corresponding study, this procedure showed an 83% risk reduction with early use, and an approval procedure is underway with the U.S. Food and Drug Administration [5]. Particularly in high-risk patients, such as those on B-cell-depleting therapy, the use of antibody treatment may still be considered later in the course of the disease if there is a suspicion that the patient’s own production is insufficient. This is recommended by the German STAKOB (Standing Working Group of Competence and Treatment Centers for Diseases Caused by Highly Pathogenic Pathogens), especially in cases of high viral loads. In addition, STAKOB said, anti-spike antibodies should be taken, and there is no need to wait for the results. With antibody therapy, the risk of allergic reactions must not be neglected; close clinical monitoring with a follow-up period of at least one hour is necessary.

Regarding the efficacy of REGEN-COV, certain gaps are evident in both the South African and the Brazilian and Scottish variants. In contrast, the newer sotrovimab (VIR-7831) appears to be fully effective in this setting as well. With the ongoing emergence of additional variants, there are likely to be some challenges ahead for physicians and the pharmaceutical industry. It is important to maintain close monitoring throughout all phases of the pandemic and to stay up-to-date at the individual level. This is the only way to ensure the best possible care.

Vaccinate, vaccinate, vaccinate

In the context of vaccination, too, the emergence of new variants is a constant focus of attention – with concerns about the efficacy of active immunization that cannot be dismissed out of hand. This varies between the different virus variants. And here, too, those affected by hematological diseases represent a special case. For example, an analysis of 88 patients after hematopoietic stem cell transplantation who had received mRNA vaccination showed that 41% did not develop adequate vaccine protection [6]. Vaccine response was particularly poor when immunosuppression had been performed within the previous three months, transplantation had occurred less than one year previously, and the lymphocyte count was <1 G/L – all factors already known from other vaccinations.

However, even with a proven poorer vaccination response, the experts at the annual conference agreed that vaccination remains the most important preventive measure – and the low vaccination rate the biggest problem. This is because even if vaccination protection is lower in immunocompromised patients, vaccination does no harm. This is also recommended before, during, or after hematologic oncology therapy – regardless of the type of treatment. Since protection is not only B-cell but also T-cell mediated, even B-cell depletion and high-dose therapy with hematopoietic stem cell transplantation are not absolute contraindications according to the currently valid Onkopedia guidelines [7]. However, the response to vaccination falls higher with increasing time interval from hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Therefore, taking into account the infectious situation, a wait-and-see approach may be warranted.

Great hope currently lies in the third dose of vaccine, which is expected to increase the response and duration of the vaccine response. For organ transplant patients, it has already been shown to have a lasting effect on the immune response [8]. The risk of severe courses in the general population can also be significantly reduced by the third dose, according to Israeli data [9]. This is increased by a factor of 19.5 in those over 60 years of age without booster vaccination, according to the data. Prof. Wendtner suspects that this effect may also be noticeable in patients with hematological malignancies. In a study of patients after allogeneic stem cell transplantation, the third vaccination showed a significant improvement in vaccine response. However, even here, 22% of study participants failed to achieve a sufficient vaccination response [10]. According to Prof. Wendtner, depending on the situation, booster vaccination is already possible after 3-4 months, and simultaneous administration with influenza vaccination is unproblematic and is an option. In any case, the third vaccination should be done with an mRNA-based agent, even if a vector vaccine was used beforehand, he said. The expert also advises low-threshold monitoring of vaccination response in hematology and oncology patients to provide reassurance to patients and practitioners.

Source: Lectures “COVID 19 in Hematological Diseases” by Clemens-Martin Wendtner and “COVID-19 in Allogenic Stem Cell Recipients” by Eduard Schulz at the scientific symposium “COVID 19 – Part 1”. Annual Meeting of the German, Austrian and Swiss Societies of Hematology and Medical Oncology, Oct. 02, 2021, Berlin (D).

Literature:

- Williamson EJ, et al: Factors associated with COVID-19-related death using OpenSAFELY. Nature 2020; 584(7821): 430-436.

- Kiani A, et al: Preinfection laboratory parameters may predict COVID-19 severity in tumor patients. Cancer Med 2021; 10(13): 4424-4436.

- Avanzato VA, et al: Case Study: Prolonged Infectious SARS-CoV-2 Shedding from an Asymptomatic Immunocompromised Individual with Cancer. Cell 2020; 183(7): 1901-1912.e9.

- Hatzl S, et al: Antifungal prophylaxis for prevention of COVID-19-associated pulmonary aspergillosis in critically ill patients: an observational study. Crit Care 2021; 25(1): 335.

- O’Brien MP, et al: Subcutaneous REGEN-COV Antibody Combination to Prevent Covid-19. N Engl J Med 2021; 385(13): 1184-1195.

- Redjoul R, et al: Antibody response after second BNT162b2 dose in allogeneic HSCT recipients. Lancet 2021; 398(10297): 298-299.

- Lilienfeld-Toal M, et al: Coronavirus infection (COVID-19) in patients* with blood and cancer – Onkopedia guideline. Status April 2021. www.onkopedia.com/de/onkopedia/guidelines/coronavirus-infektion-covid-19-bei-patient-innen-mit-blut-und-krebserkrankungen/@@guideline/html/index.html.

- Kamar N, et al: Three doses of an mRNA Covid-19 vaccine in solid-organ transplant recipients. N Engl J Med 2021. 385: 661-662.

- Bar-On YM, et al: Protection of BNT162b2 vaccine booster against Covid-19 in Israel. N Engl J Med 2021; 385(15): 1393-1400.

- Redjoul R, et al: Antibody response after third BNT162b2 dose in recipients of allogeneic HSCT. Lancet Haematol 2021; 8(10): e681-e683.

InFo ONCOLOGY & HEMATOLOGY 2021; 9(6): 23-24 (published 8/12/21, ahead of print).