Osteoporosis is a wide-ranging health problem, but there are a variety of preventive and therapeutic options available today. Early detection and risk stratification are important prerequisites for patient-adapted prevention and treatment. In 2020, the Swiss Association Against Osteoporosis updated its recommendations on prevention, diagnosis and therapy.

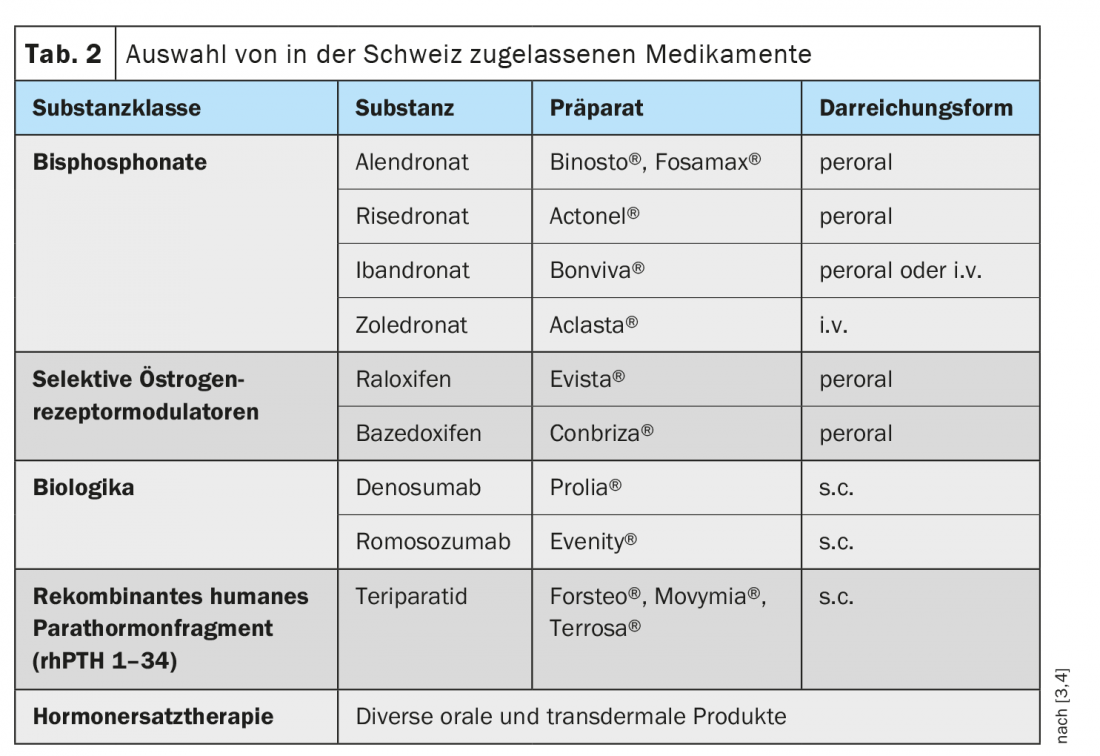

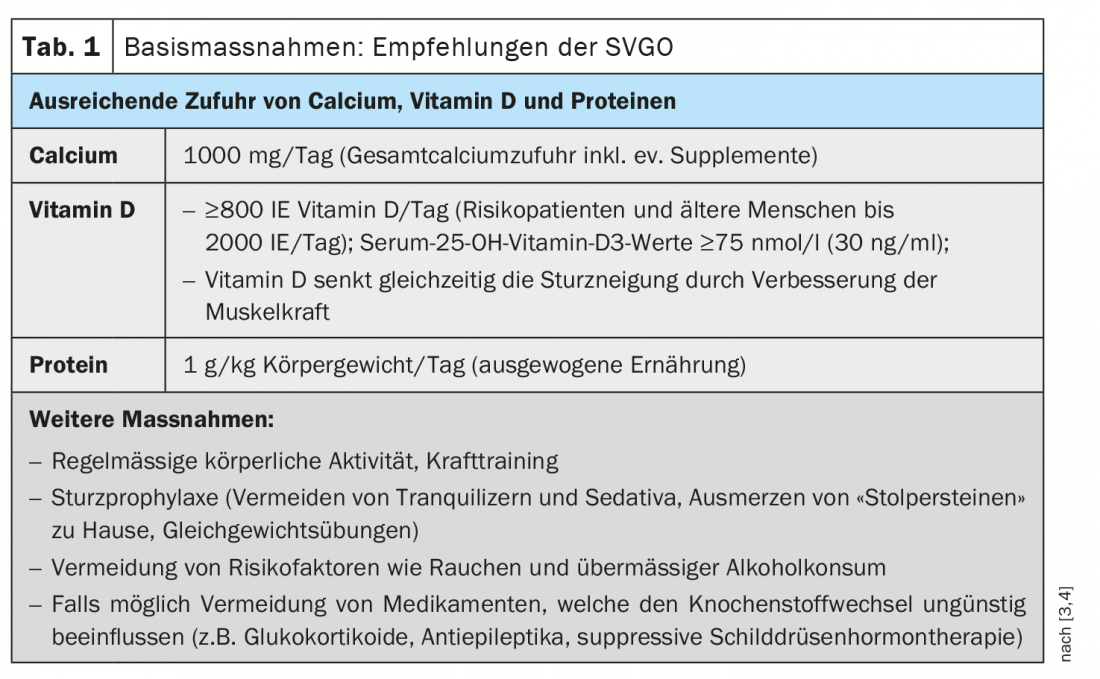

Osteoporosis usually manifests itself in women after the age of 45 and in men after the age of 55 [1]. Secondary or idiopathic forms of osteoporosis in younger individuals are rare. That women are more than twice as likely as men to be affected by osteoporosis is primarily due to hormonal changes after menopause, with epidemiologic data showing an age-correlated increase in prevalence from 15% in those aged 50-60 years to 45% in those over 70 years [2]. The earlier osteoporosis is detected, the better the treatment options. In addition to calcium and vitamin D (Tab. 1), numerous very effective osteoporosis drugs are available today whose active ingredients can slow excessive bone loss and/or specifically promote bone formation (Tab. 2).

Risk stratification as an important basis for treatment

In the 2020 updated recommendations, the Swiss Osteoporosis Association (SVGO) addresses risk stratification and, based on this, risk-adapted therapy [3,4]. The FRAX score is currently the best validated risk factor assessment tool applicable to men and women over 45 years of age. There are also some limitations, for example that it can only be used in untreated patients (exception: administration of calcium and vitamin D) and the spine is not assessed. Bone densitometry is used to confirm the diagnosis of osteoporosis. FRAX and densitometry (DXA) are complementary diagnostic measures. And even if estrogen deficiency in women is the most likely cause of osteoporosis or increased fracture risk, other causes should be excluded by differential diagnosis.

Medical history and FRAX: The FRAX (WHO Fracture Risk Assessment) algorithm can be used to estimate the absolute 10-year risk of major fractures of the hip, spine, forearm, or proximal humerus [5,6]. The evaluation of the FRAX score is based on several risk factors. In addition to age and gender, these include a BMI <20, a fracture after age 40 (except hands, feet, skull), and a fracture of the neck of the femur in a parent. Furthermore, rheumatoid arthritis and current or previous oral glucocorticoid therapy for a period of at least 3 months daily (≥5 mg prednisolone equivalent) are risk factors. Regarding lifestyle factors, smoking and alcohol consumption of more than three units daily are mentioned.

Densitometry by dual X-ray absorptiometry (DXA): This imaging technique should be used when clinical risk factors indicate an increased risk of osteoporosis. A DXA measurement is performed on the lumbar spine (mean value of assessable vertebrae L1-L4), on the total femur and on the femoral neck (single measurement or mean value of femur left and right). For the estimation of the 10-year fracture risk, the lowest value of lumbar spine, femoral neck and total femur is decisive. The result of the DXA measurement is expressed as a T-score and shows, in the form of standard deviations, how great the deviations of the measured bone density are from the bone density of young healthy adults. A value of -1 to -2.5 is a precursor of osteoporosis, and a value below -2.5 is osteoporosis [7].

New assignment of the fracture risk group: The following five fracture risk groups have recently been distinguished:

1.

Immediate risk of fracture (imminent), i.e. >10% risk of fracture within the next 2 years:

Age 65+ and osteoporotic fracture (vertebral body, hip, humerus, radius, pelvis) during the past 2 years.

2.

Very high risk of fracture:

The 10-year fracture risk for an osteoporotic fracture (vertebral body, hip, humerus, radius, pelvis) according to FRAX is at least 20% above the intervention threshold.

3.

High risk of fracture:

Osteoporotic fracture (vertebral body, hip, humerus, radius, pelvis) more than 2 years ago and/or the 10-year fracture risk for an osteoporotic fracture (vertebral body, hip, humerus, radius, pelvis) according to FRAX is higher than the intervention threshold but less than 20% above it. This group also includes individuals on long-term therapy with glucocorticoids, aromatase inhibitors (female), or androgen suppressants (male) whose DXA-T value is <1.5 and/or in whom the 10-year fracture risk for an osteoporotic fracture (vertebral body, hip, humerus, radius, pelvis) according to FRAX is above the intervention threshold.

4.

Moderate fracture risk:

DXA-T value ≤ -2.5 and no previous fractures and 10-year fracture risk for an osteoporotic fracture (vertebral body, hip, humerus, radius, pelvis) according to FRAX below the intervention threshold.

5.

Low fracture risk:

Osteopenia and no other risk factors

Therapeutic measures are based on the fracture risk

The appropriate treatment strategy is determined with reference to the fracture risk group, provided that other causes of osteoporosis or increased fracture risk have been excluded. Implementation of the basic measures (Tab. 1) is recommended for each risk group. Various substance classes are available for specific therapy (Tab. 2) . The following procedure is suggested in the recommendations of the SVGO, whereby it is pointed out that the respective contraindications must be taken into account.

Very high/imminent fracture risk in post vertebral fracture condition:

Teriparatide for 18-24 months, followed by maintenance therapy with bisphosphonates or denosumab.

Very high/imminent fracture risk in post hip fracture condition: Bisphosphonate zoledronate (alternative: denosumab).

Very high/imminent risk of fracture in the setting of any osteoporotic fracture of the vertebral body, hip, humerus, radius, or pelvis:

Romosozumab for one year (withhold if increased cardiovascular disease risk), followed by bisphosphonates or denosumab

High fracture risk:

Bisphosphonates or denosumab (alternative: teriparatide in condition after vertebral fracture or T value <-3.5 SD at spine).

Moderate risk:

Hormone replacement therapy, Selective estrogen receptor modulators, possibly oral bisphosphonates if bone metabolism markers (CTX, PINP) are above the premenopausal reference range.

Low risk: Possibly hormone replacement therapy (HRT) for menopausal syndrome.

Progress monitoring is a very important factor. Follow-up by densitometry/DXA should be performed after every 2 years, with the exception of the low-risk group (DXA only after 5-10 years).

How can rebound effects be avoided?

Denosumab (Prolia®) and romosozumab (Evenity®) are both very effective osteologic biologics (osteologics), but can lead to a loss of the gained bone mass after discontinuation, a so-called “rebound” effect [8,9]. After discontinuation of Prolia® , bisphosphonates such as zoledronate (e.g. Aclasta®) or alendronate (e.g. Fosamax®) are recommended for follow-up treatment [11]. According to current knowledge, rebound can be most efficiently counteracted by zoledronate (Aclasta®) i.v. 5 mg 1× per year, first administration 6 months after last Prolia® application, alternatively aledronate can be used [8,10]. Bone remodeling markers should be measured every three to six months to monitor follow-up [11]. A direct switch from Prolia® to an osteoanabolic therapy such as teriparatide (e.g. Forsteo®) should be avoided, as this increases the rebound effect [8]. A combination of Prolia® and Forsteo® has an additive effect, whereas the combinatin of biphosphonates and Prolia® is not recommended [8,12].

Romosozumab (Evenity®) has been approved in Switzerland since 2020 for the treatment of severe osteoporosis in women who show a significantly increased risk of bone fractures after menopause [9]. Application is 1× monthly, maximum duration of therapy is 12 months, after which biphoshonate therapy is required. Contraindications to romosozumab therapy include a history of stroke or myocardial infarction [8].

Literature:

- OsteoSwiss, www.osteoswiss.ch (last accessed Mar. 16, 2021).

- Gourlay ML, et al: Bone-density testing interval and transition to osteoporosis in older women. N Engl J Med 2012; 19; 366(3): 225-233.

- Ferrari S, Lippuner K, Lamy O, Meier C: 2020 recommendations for osteoporosis treatment according to fracture risk from the Swiss Association against Osteoporosis (SVGO). Swiss Med Wkly 2020, 150:w20352

- Stute P, Meier C: Update osteoporosis. J Gynecol Endocrinol 2021, https://doi.org/10.1007/s41975-021-00181-4

- FRAX® Fracture Risk Assessment Tool, www.shef.ac.uk/FRAX (last accessed 03/16/2021).

- Kanis JA, et al: Assessment of fracture risk. Osteoporos Int 2005; 16(6): 581-589.

- “Osteoporosis: detecting bone loss early,” Oct. 17, 2020, https://nachrichten.idw-online.de, (last accessed Mar. 16, 2021).

- Mollet S: Osteoporosis – an update, Stella Mollet, MD, Continuing Medical Education Forum, June 26, 2020.

- Swissmedic: Medicinal product information, www.swissmedicinfo.ch (last accessed 16.03.2021).

- Anastasilakis AD, et al: Zoledronate for the Prevention of Bone Loss in Women Discontinuing Denosumab Treatment. A Prospective 2-Year Clinical Trial. J Bone Miner Res 2019; 34(12): 2220-2228.

- “Prolia® and Evenity®: How to prevent rebound?”, Jan. 28, 2021, www.rheumaliga.ch/blog/2021/prolia-evenity-rebound-effekt

- Leder BZ, et al: Response to Therapy With Teriparatide, Denosumab, or Both in Postmenopausal Women in the DATA (Denosumab and Teriparatide Administration) Study Randomized Controlled Trial. J Clin Densitom 2016; 19(3): 346-351.

HAUSARZT PRAXIS 2021; 16(4): 22-23