Middle-aged patients may well still be diagnosed with Asperger syndrome. Most of the time, these are people with a high level of compensation. But the efforts take over as time goes on, leaving sufferers to seek help.

Asperger’s syndrome is currently attracting a great deal of cultural and public interest. This development, which on the one hand is gratifyingly de-tabooing, also brings with it many myths, prejudices and a glorification. This leads some professionals to be overly cautious about the diagnosis. Skepticism is especially prevalent for those adults who are first diagnosed in middle age. But this skepticism is mostly unjustified. Many affected persons can demonstrate a high level of compensation over a long period of time and only decompensate in the middle of life, when the ongoing stress finally outweighs their resources. These individuals do not seek help for the first time for secondary disorders until they are adults in middle age or older. Comorbidities are particularly common in people with ASD [1]. Other affected persons turn to a professional only after a long independent confrontation with their problem, which leads them to self-diagnosis. Both groups should be correctly diagnosed to spare them unnecessary suffering. The following is a rudimentary description of how to properly identify, diagnose, and treat affected individuals with high compensation in adulthood.

Diagnostic criteria

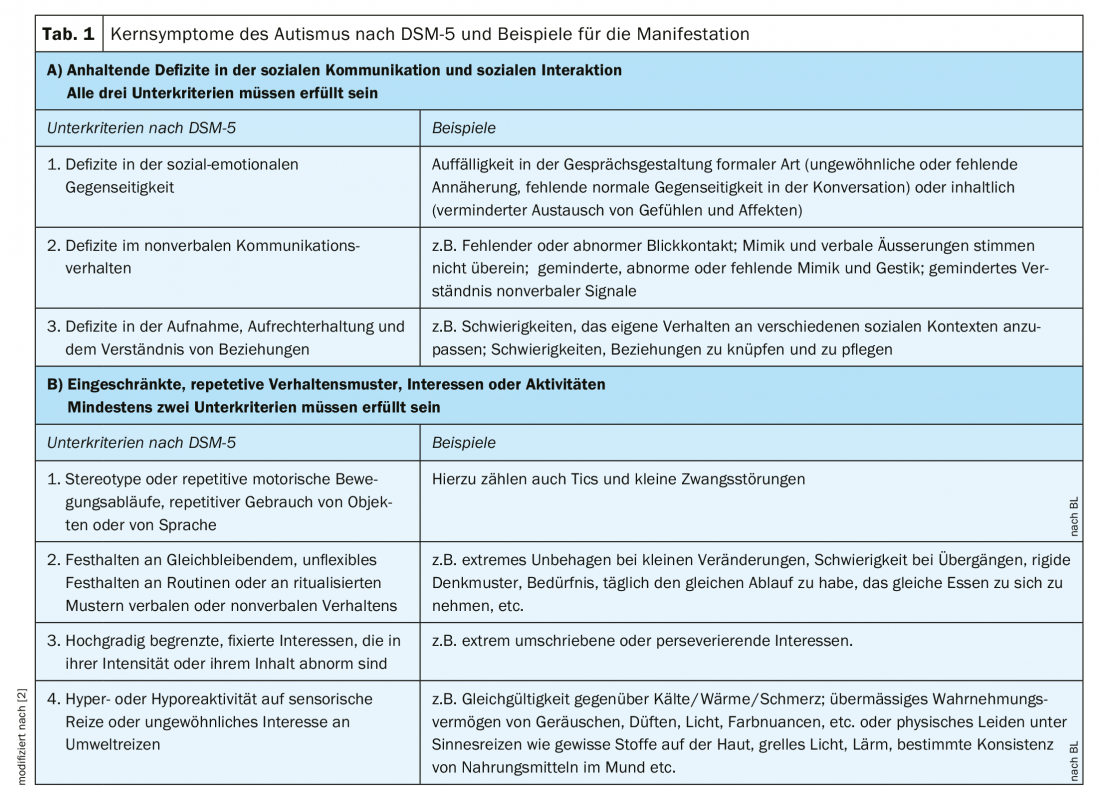

In the DSM-5 and the expected ICD-11, autistic problems are no longer understood categorically, but in a new dimensional way. That is, the different diagnoses of Early Childhood Autism, Atypical Autism, and Asperger’s Syndrome are recorded as different manifestations of the same continuum with the same core features. There are essentially two observable characteristics that make up the autism spectrum according to the diagnostic systems: problems in interpersonal interaction and restricted, repetitive patterns of behavior, interests, or activities. No reference is made to the underlying mechanisms.

Table 1 shows the autism-defining criteria according to DSM-5 [2]. To test whether these criteria are met, the clinician looks for conspicuousness in the patient’s conversational manner, nonverbal behavior, and relational network and patterns. While some patients are immediately noticeable in this respect – they walk directly to their chair without any greeting phrases, talk incessantly or not at all, seem know-it-all, lack eye contact, their voice is too loud/too quiet/shrill, etc. – other affected persons are quite capable of the usual forms of politeness. Some have – like other people – a natural charm, which can be advantageous in life, but misleading in diagnostics. These affected persons succeed in social interaction with initially no or only little conspicuousness. The professional therefore does not immediately think of autism. Exploration, however, reveals that this active adaptation requires considerable effort on their part. For example, entire scripts for conversations are created before any telephone calls (sometimes including greetings), a longer recovery period is needed after interactions, small talk and flirting are only possible in writing or not at all. Bullying and exclusion experiences have also often been experienced by these patients in the past. If one inquires about their social relationships and relationship patterns, subjectively and externally, the above criteria are found to be fulfilled: Often the initially normal-appearing conversational manner is learned and practiced consciously – not intuitively. The friendly appearing facial expression is often parathymic and does not represent an indicator for the current feelings, the eye contact is also learned and is made consciously with effort. One’s own verbal and non-verbal expression, as well as deciphering the facial expressions of others or verbal communication in multi-person conversations are only accomplished with the help of considerable effort, which causes subjective stress and gradually leads to exhaustion.

Furthermore, some professionals who are not familiar with the topic think that people with autism do not want or cannot maintain social relationships. But this is not the case. On the contrary, the vast majority of affected individuals have an intact need for attachment and social interest. Maintaining relationships per se is definitely not an exclusion criterion for an ASD. Often, however, the need is merely somewhat reduced and the satisfaction of the need may be shaped differently than in non-autistic people. For example, fact-focused rather than emotion-focused (e.g., based on shared interests rather than shared experiences or feelings), or relationship maintenance manifests in fixed, albeit infrequent, intervals.

The same applies to the second criterion of repetitive and restricted interests and sensory over- or under-sensitivity. Here, too, some patients are immediately noticeable because, for example, they seem obsessive, complain about the smell or the glaring neon light, wear very loose and soft clothes, and the like. However, those with a high level of compensation would not complain out of learned politeness, often their clothing is also adapted and they do not stand out at first. Some are aware of their own system, but do not recognize their own need for routine and adherence to fixed routines as noticeable or are unaware that their perception is different from others. Only when they and their relatives are explicitly asked about their routines and fixed procedures as well as about sensory hypersensitivities (regarding all five senses individually, as well as temperature and pain), one receives clear confirmation.

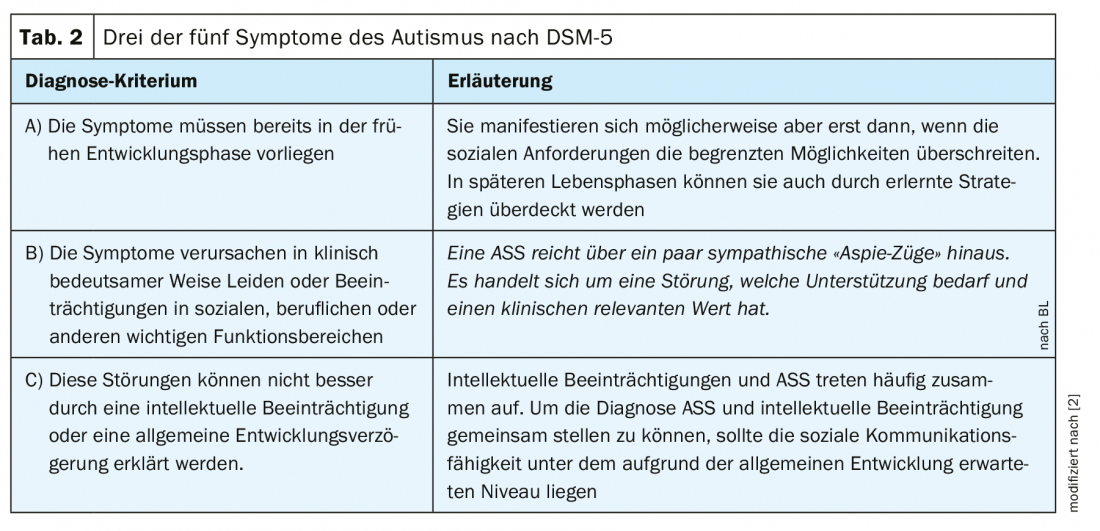

ASD is a developmental disorder, which is why it must have been present in childhood. However, many affected individuals are not conspicuous in childhood, which does not rule out the presence of autistic traits in childhood. The following two reasons in particular explain this: 1. ASA is strongly genetically determined [3]. Thus, if other members of the family are also affected, the individual does not appear to be conspicuous in his or her social setting. 2. often the children are able to adapt, albeit with difficulty, to a large extent, appearing at most somewhat ‘special’, and it is only when the social demands exceed their ability to adapt, possibly for the first time as adults, that the autistic difficulties are recognized. This is not uncommon, so this circumstance is explicitly mentioned in DSM-5 (Tab. 2).

Diagnostics in adult age

Currently, there is no valid method that can unambiguously answer the question whether a person suffers from ASD or not. The diagnostic process requires a detailed interview and an attentive and experienced interviewer, and also usually includes a small battery of testing procedures that together indicate whether the diagnostic criteria for ASD and other differential diagnoses are met. An integral part of the diagnostic process is the external medical history. This is to gain more information, beyond the patient’s self-description, about the first two diagnostic criteria. In this context, it is also ascertained whether the ASD peculiarities were already expressed in childhood. The assessment may also include questions about other abnormalities that are common but not currently part of diagnostic criteria, such as detail-focused perception and an exaggerated sense of justice.

Mode diagnosis?

Over the past 30 years, the frequency of diagnosis has increased rapidly (from 0.1% in 1980s to about 1-2% in 2020 [4,5]). The reasons are probably three:

- The successive inclusion of diagnoses in the DSM and ICD classification systems (1978, 1994, 2013 [2,6]) makes it possible to diagnose more and more people.

- The public interest and cultural presence of Asperger syndrome is leading to more awareness in the general population and

- The currently rapidly changing world, which demands a high degree of mobility and flexibility and places social skills at the center, overtaxes people with autistic traits in particular.

This increase in prevalence again causes some professionals to doubt the diagnosis. The doubt is understandable but not justified. Individuals who are first diagnosed with mild ASD in adulthood would most likely have been diagnosed with several other diagnoses or semi-diagnoses (e.g., social phobia and obsessive-compulsive personality disorder, accentuated personality, combined personality disorder, etc.) without this one diagnosis. However, these substitute diagnoses would not have the same explanatory value, leading to non-successful or less successful therapy. The impression of autism specialists is that despite the media and cultural presence of the diagnosis, autism spectrum disorder is still underdiagnosed in Switzerland [7]. It is not uncommon for those affected to suffer from rejection of this diagnosis by professionals who are not very familiar with it.

The treatment

The autistic idiosyncrasies cannot be treated away. However, some things can be done to significantly improve the well-being, functional level and thus the quality of life of those affected. In the process, certain skills can be learned and trained to a certain individual degree, an adjustment of the environmental situation can be sought (job, workload, place of residence, etc.) and consequential disorders and stresses can be treated. Consequently, therapy is strongly recommended when there is an existing condition. It is of great advantage to the affected person if the therapist is knowledgeable in the field of ASD [8].

The peculiarities of ASD must already be taken into account when establishing the relationship. The following are some examples. People with ASD appreciate clear, concrete language. Therefore, ambiguities, imprecise formulations, and rhetorical questions or insinuations should be avoided in order not to overburden the person concerned.

In addition, the therapist should strike a balance between directivity on the one hand and respect for the patient’s increased need for autonomy on the other. Further, more patience than usual is often required of therapists in the therapy process. Virtually all sufferers want clear instructions from therapists, some follow them remarkably obediently, while others have difficulty engaging with new things and therefore initially show resistance and need more time. Finally, great care must be taken to ensure sensitivity. Often, those affected have gone through multiple experiences of exclusion and rejection in the past. It is therefore not only nice but essential for them to experience an appreciative, benevolent and compassionate therapeutic relationship.

The first step of the therapy is psychoeducation: explanation about ASD, classification of the patient’s difficulties into this diagnosis and pointing out the treatment options. It is also essential to analyze the patient’s resources.

As a rule, the subsequent diseases for which the patient reported for treatment are subsequently treated, taking into account the ASA properties. The most common comorbidities are depression and adjustment disorders, ADHD, anxiety, sleep, impulse control, and obsessive-compulsive disorders, as well as social behavior disorders and psychosis [1].

Other typical problems that significantly affect the quality of life of those affected include involuntary unemployment or occupational underachievement in the face of good vocational training, problems with stress regulation, emotion regulation, feelings of self-sufficiency, social skills, frequent suicidal ideation, and problems with practical day-to-day coping [9–12]. The latter can include things like impaired time management and self-organization to inadequate food intake.

Basically, it is necessary to work out an individual analysis of the problems with the patient. This should be followed by a pragmatic, solution-oriented, realistic plan to improve skills and life circumstances. Meanwhile, some manuals for the improvement of different skills are available [13–15]. Experienced therapists have a repertoire of techniques that have proven successful in teaching skills and dealing constructively with ASD problems. Improving living conditions often includes discussions with employers, reorganization of the professional task or its scope, and sometimes the place of residence, etc., as well as discussions with relatives.

In addition to improving skills, coping and living conditions, therapy should also provide support for acceptance of individual limitations. The latter initially means disappointment for some of those affected, because their wishes, hopes and ambitions are not always compatible with their resources. Over time, a shift in focus should be achieved, focusing on well-being, one’s own values, and self-esteem. The goal is to develop self-fulfillment and sense-making while respecting well-being.

Take-Home Messages

- An ASD initial diagnosis is also possible in middle age.

- Maintaining social contacts per se is not an exclusion criterion for ASD.

- Flexible response cannot be required of people with ASD by definition.

- A comprehensive procedure is necessary to make a diagnosis. The collection of a screening sheet alone is not sufficient.

- Psychotherapy can help patients considerably, even if core symptoms remain.

Literature:

- Lai MC, Kassee C, Besney R, et al: Prevalence of Co-Occurring Mental Health Diagnoses in the Autism Population: a Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Lancet Psychiatry: 2019; 6: 819-829.

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (5th ed.) DSM-5 Diagnostic Criteria: 2013. German edition edited by Peter Falkai and Hans-Ulrich Wittchen: 2015.

- Sandin S, Lichtenstein P, Kuja-Halkola R, et al: The heritability of autism spectrum disorder. JAMA: 2017; 318 (12): 1182-1184.

- Weintraub K: The Prevalence Puzzle. Autism Counts. Nature, 2011; 479(3), 22-24.

- www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/autism/data.html

- World Health Organization. International Classification of Diseases. (9th edition 1978, and10th edition, 1994).

- Haker H: Asperger syndrome – A fashionable diagnosis? Practice, 2014; 103:1191-1196.

- Lipinski S, Blanke ES, Suenkel U, Dziobek I: Outpatient Psychotherapy for Adults With High-Functioning Autism Spectrum Condition: Utilization, Treatment Satisfaction, and Preferred Modification. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2019; 49, 1154-1168.

- Kirchner JC, Dzibek I: Towards Successful Employment of Adults with Autism. Scandinavian Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry and Psychology, 2014; 2(2), 77-85.

- Gawrosnki A, Kuzmanovic B, Georgescu A, et al: Expectation of psychotherapy for high-functioning adults with autism spectrum disorder, 2011; Progress in Neurology Psychiatry, 79, 647-654.

- Attwood T.: Cognitive Behavior Therapy for Children and Adults with Asperger’s Syndrome. Behaviour Change, 2004; 21(3), 147-161.2004.

- Cassidy S, Bradley P, Robinson J, et al: Suicidal Ideation and Suicide Plans or Attempts in Adults with Asperger’s Syndrome Attending a Specialist Diagnostic Clinic: A Clinical Cohort Study. The Lancet Psychiatry, 2014; 1(2), 142-147.

- Gawronski A, Pfeiffer K, Vogeley K: High-functioning autism in adulthood. Behavioral therapy group manual. 2012; Beltz Publishers.

- Ebert D, Fangmeier T, Lichtblau A, et al: Asperger’s autism and high-functioning autism in adults. The therapy manual of the Freiburg Autism Study Group. 2013; Hogrefe Verlag.

- Dziobek I, Stoll S: High-functioning autism in adults. A Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy Manual. 2019; Kohlhammer Verlag.

InFo NEUROLOGY & PSYCHIATRY 2020; 18(3): 12-15.