About 50 percent of all Swiss over the age of 30 have pathologically enlarged hemorrhoids. Symptomatic hemorrhoidal disease is one of the most common conditions associated with significant impact on quality of life. Treatment options for hemorrhoids are varied, ranging from conservative measures to a variety of surgical procedures.

Overall, about 40% of people with hemorrhoids are asymptomatic. In symptomatic hemorrhoids, there is great variation in the constellation of symptoms. In addition, many other anorectal pathologies such as anal fissure, fistula, pruritus, condyloma and even anal cancer are often referred to as “hemorrhoids” by the layman. In internal hemorrhoids, bleeding is the most commonly reported symptom. The occurrence of bleeding is usually associated with a bowel movement and is almost always painless. The blood is bright red and covers the stool. Another common symptom is the sensation of tissue prolapse. Prolapsed internal hemorrhoids may present with mild fecal incontinence, mucous secretion, bloating, and irritation of the perianal skin. Pain is significantly less common with internal hemorrhoids than with external hemorrhoids. However, they may occur in prolapsed, strangulated internal hemorrhoids that develop gangrenous changes due to associated ischemia. In contrast, external hemorrhoids are more likely to be associated with pain due to activation of perianal innervations associated with thrombosis. Patients typically describe a painful perianal mass that is tender to palpation. This painful mass may initially increase in size and severity over time. Bleeding may also occur when ulceration occurs due to necrosis of thrombosed hemorrhoids, and this blood tends to be darker and more clotted than bleeding due to internal disease.

Management of hemorrhoids

Most cases of hemorrhoids are self-limiting. For symptomatic hemorrhoidal disease presenting to the clinic or emergency department, treatments range from nonoperative medical interventions to surgery. The least invasive approaches are considered first – except in cases of acute thrombosis. The specific choice of treatment depends on the patient’s age, symptom severity, and comorbidities.

Conservative medical treatments

Lifestyle and dietary changes are the cornerstones of conservative medical treatment for hemorrhoids. Specifically, lifestyle changes should include increasing oral fluid intake, reducing fat consumption, avoiding exertion, and regular exercise. Dietary recommendations should include increasing fiber intake, which reduces the shear effect of passing hard stool. Topical treatments with various local anesthetics, corticosteroids, or anti-inflammatory drugs are available for symptomatic control. With the exception of thrombosis, internal and external hemorrhoids respond readily to conservative medical therapy. When symptoms cannot be relieved by medical intervention or when the extent of hemorrhoidal disease is severe, the colorectal surgeon has several options for invasive procedures.

Non-surgical procedures

For internal hemorrhoids, rubber band ligation, sclerotherapy, and infrared coagulation are the most common procedures, but there is no consensus on optimal treatment. Overall, the goal of each procedure is to decrease vascularity, reduce redundant tissue, and increase fixation of the hemorrhoidal rectal wall to minimize prolapse.

Rubber band ligation: Rubber band ligation is the most commonly performed procedure and is indicated for grade II and III internal hemorrhoids. Contraindications include symptomatic external disease and patients with coagulopathies or chronic anticoagulation (due to risk of delayed bleeding). There is also an increased risk of sepsis in immunocompromised patients. Local anesthesia is not required to perform rubber band ligation. Patients are placed in the jackknife or left lateral position and the procedure is performed through an anoscope. Small rubber band rings are placed tightly around the base of the internal hemorrhoids. They should be placed at least half a centimeter above the tooth line to avoid placement in somatically innervated tissue. Rubber band ligation causes hemorrhoid necrosis and its fixation to the rectal mucosa. When the tissue becomes ischemic, necrosis develops over the next 3 to 5 days, and an ulcerated tissue bed forms. Complete healing occurs a few weeks later. Complications are very rare but may include pain, urinary retention, delayed bleeding, and very rarely perineal sepsis.

Infrared coagulation: infrared coagulation refers to the direct application of infrared light waves to hemorrhoidal tissue and can be used for grade I and II internal hemorrhoids. To perform this procedure, the tip of the infrared coagulation applicator is typically applied to the base of the internal hemorrhoid for two seconds, with three to five treatments per hemorrhoid. By converting infrared light waves into heat, the applicator causes necrosis of the hemorrhoids, which becomes visible as a white, blanched mucosa. Over time, the affected mucous membranes are scarred, leading to retraction of the prolapsed hemorrhoidal mucosa. This procedure is very safe, with only minor pain and bleeding reported.

Surgical measures

Continued symptoms despite conservative or minimally invasive measures usually require surgical intervention. In addition, surgery is the first treatment of choice in patients with symptomatic grade IV hemorrhoids or in patients with strangulated internal hemorrhoids. It may also be required in symptomatic grade III hemorrhoids and in patients with thrombosed hemorrhoids. In patients with thrombosed external hemorrhoids, surgical exploration and intervention within 72 hours of thrombosis may result in significant relief, as pain and edema peak at 48 hours. After 48 to 72 hours, however, there is organization of the thrombus and improvement of symptoms. After the initial 72-hour window, the pain usually resolves and slowly improves. At this point, the pain from hemorrhoid excision would exceed the pain from the thrombosis itself.

Surgical hemorrhoidectomy: Surgical hemorrhoidectomy is a relatively morbid procedure compared to other less invasive procedures. Due to the extent of the dissection and the presence of incisions below the tooth line, postoperative pain can be severe and delay the return to normal activities by several weeks. Pain can usually be treated with oral analgesics, avoidance of constipation, and sitz baths. After one week after surgery, bleeding may occur in 1 to 2% of patients due to scab separation. Infection is rare after hemorrhoid surgery with submucosal abscesses in less than 1% of cases and severe fasciitis or rarely necrotizing infections.

Despite the relatively higher morbidity, surgical hemorrhoidectomy is more effective than band ligation in preventing recurrent symptoms. In a randomized trial, no differences were found between open and closed hemorrhoidectomy in elective cases. Patients with grade III and IV hemorrhoids benefit most from surgical hemorrhoidectomy.

Stapled hemorrhoidopexy: An alternative to surgical hemorrhoidectomy is stapled hemorrhoidectomy, in which a stapling device is used to resect and fix the internal hemorrhoidal tissue to the rectal wall. Because the staple line is above the tooth line, patients typically experience less pain than those who undergo hemorrhoidectomy. To perform this procedure, a circular stapler is inserted into the anus and prolapsed tissue is brought into the stapler. The most critical component of stapled hemorrhoidopexy is the placement of a circumferential, nonabsorbable suture in the submucosa far enough away to avoid sphincter involvement-usually approximately 4 cm from the dentate line. Complications of stapled hemorrhoidopexy include bleeding from the staple line, incontinence from sphincter injury, and stenosis from storage of excess rectal tissue. In addition, women are at risk of rectovaginal fistula due to the incorporation of vaginal tissue into the purse.

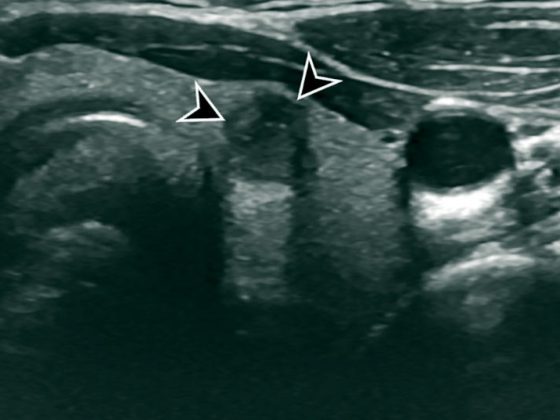

Doppler-guided ligation of hemorrhoids: First described in 1995, this technique involves the use of Doppler ultrasound to identify and ligate hemorrhoids. It is also called transanal hemorrhoid deserterialization (THD). There are different platforms with different assigned nomenclatures for this technique. However, the principles include the use of a Doppler probe to identify the six main feeding arteries in the anal canal, ligation of these arteries with absorbable sutures and a special anoscope, and subsequent redundancy hemorrhoidal mucosa. The complication is often referred to as rectoanal repair, mucopexy, or hemorrhoidopexy. The proposed advantages of this procedure are similar to stapled hemorrhoidopexy, with less pain because the suturing is done above the dentinal line. The initial results of Doppler-guided ligation of the hemorrhoidal artery (DGHAL)/THD were promising, demonstrating lower pain scores than hemorrhoidectomy and relief of bleeding and tissue prolapse in more than 90% of patients.

Cave comorbidities

Crohn’s disease: hemorrhoids should be differentiated from hypertrophic skin markings associated with Crohn’s disease. Skin patches in Crohn’s disease are often tender and associated with ulceration of the anal canal. In patients with Crohn’s disease and active anorectal inflammation, treatment of hemorrhoids should be kept as conservative as possible in any attempt to avoid surgery, as these patients may have significant problems with wound healing after hemorrhoidectomy and surgery may actually exacerbate their disease symptoms. Hemorrhoidectomy can be performed very selectively at rest but is generally not recommended.

Immunosuppression: Immunosuppressed patients such as patients with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) or patients on chronic immunosuppressive medications are at higher risk for sepsis and poor wound healing. Conservative treatments should be exhausted before performing invasive procedures.

Liver cirrhosis and portal hypertension: Contrary to previous teachings, the incidence of hemorrhoids in patients with portal hypertension does not differ from the general population. Rectal varices, the result of porto-systemic communication via the hemorrhoidal veins, often occur in patients with portal hypertension. However, rectal variceal bleeding is rare and accounts for less than 1% of massive bleeding in portal hypertension. When it occurs, it should normally be treated with portal decompression.

GP PRACTICE 2019; 14(9): 32-34