Anorectal discomfort is common, but often leads to delayed consultations due to fear or shame. The causes of anorectal complaints are often benign and a rapid diagnosis is usually possible by means of a well-founded anamnesis and clinical examination. A review of diagnosis and treatment of the most common causes of anal pain.

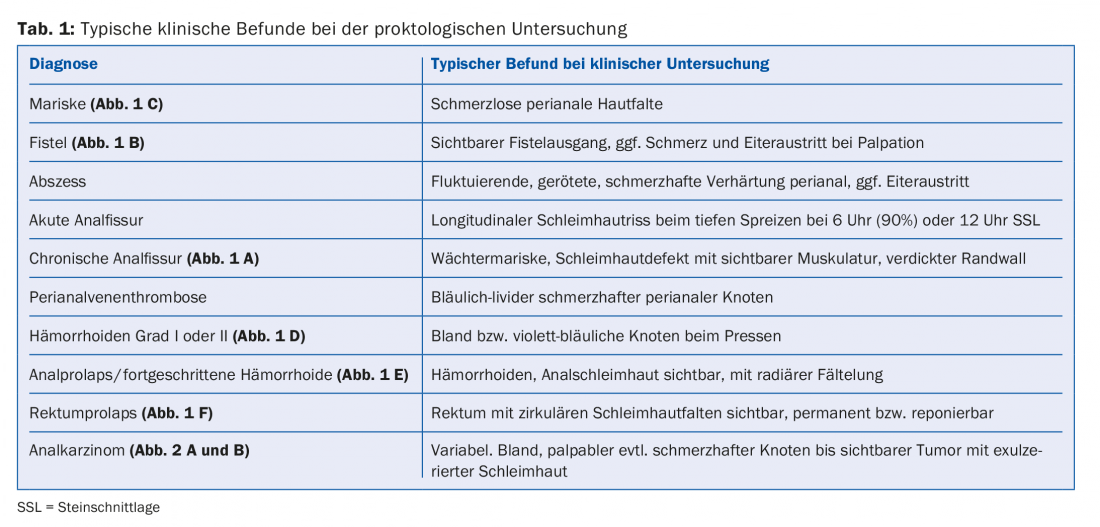

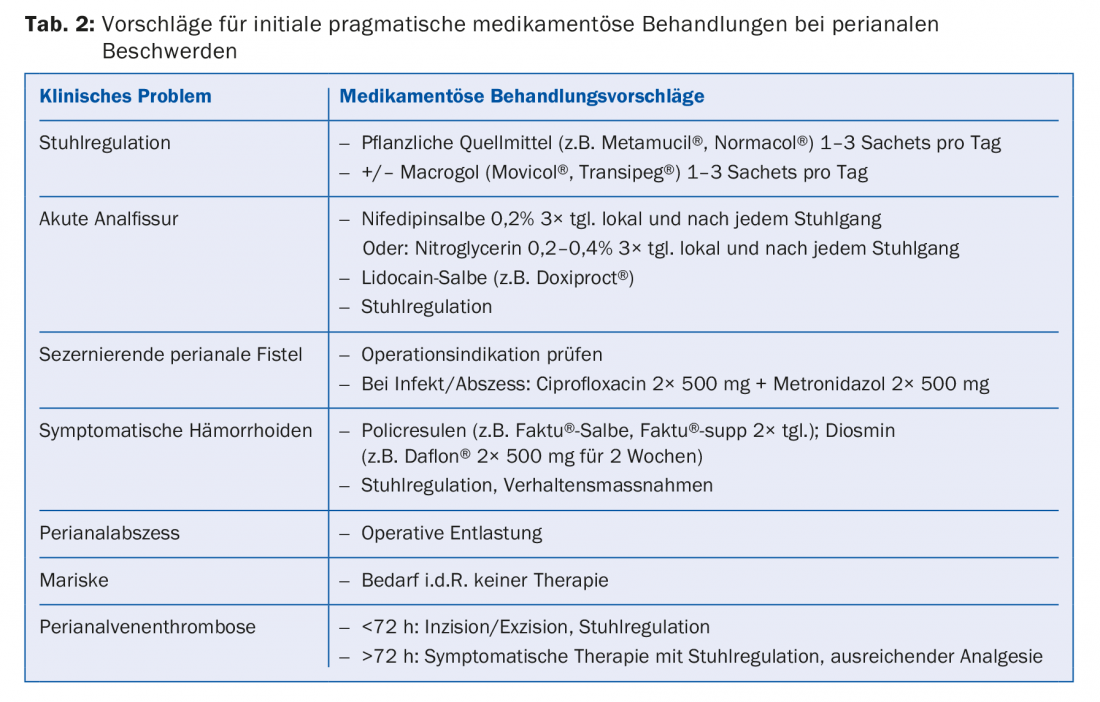

Anorectal discomfort is common, but often results in delayed consultations due to shame or fear. The causes of anorectal complaints are often benign and a rapid diagnosis is usually possible by means of a well-founded anamnesis and clinical examination. This article is intended to provide an overview of the diagnosis and treatment of the most common causes of anal pain (tables 1 and 2). Differential diagnoses include anal fissures, fistulas/abscesses, perianal vein thrombosis, and pain without morphologic correlate. Hemorrhoids, on the other hand, are not a typical cause of anal pain.

Anal fissures

Acute anal fissure typically presents with the triad: pain on defecation (lasting up to 15-30 min), constipation, and bright red blood on the toilet paper [1]. The cause of anal fissure is hard or bulky stools, rarely diarrhea, which lead to tearing of the anoderm. Anal sexual practices can also lead to fissure. 90% of anal fissures are located in lithotomy position (SSL) at 6 o’clock, 10% at 12 o’clock, this localization being more frequent in women than in men. Less than 1% are outside the center line. If the localization is correspondingly atypical, other causes such as Crohn’s disease, leukemia, HIV, tuberculosis, syphilis, carcinoma or mechanical causes must be considered. Anal fissure can often be visualized without proctoscopy on clinical examination by spreading with the finger.

In anal fissures, there is a “vicious circle” characterized by pain with subsequent muscle spasm of the internal sphincter as well as consecutive reduced perfusion. This perpetuates fissure and pain, which can contribute to chronicity.

Fissures are described as chronic if they persist for more than six weeks despite adequate therapy. These can lead to profound destruction up to the internal anal sphincter (IAS). Symptomatically, itching or burning with traces of blood on the paper are more prominent [2]. Local findings of a chronic fissure typically show a hypertrophic anal papilla, a mucosal defect with thickened margins, a visible IAS, and a sentinel (guardian) marrow ( Fig. 1 A).

According to the pathogenesis, the therapy pursues three goals:

- Atraumatic chair passage

- Sphincter relaxation

- Analgesia (systemic and local).

Optimal stool regulation is the indispensable basis of therapy. Calcium channel blockers such as diltiazem or nifedipine (e.g., nifedipine 0.2% in ointment form, 3× daily) are used for sphincter relaxation and should be applied topically. Alternatively, topical nitroglycerin in 0.2% or 0.4% concentration can be used for 6-8 weeks, but this often leads to side effects, especially headache (20-70%) [3]. The efficacy of the two classes of products is comparable [4], so that calcium channel blockers are usually used initially because of the lower spectrum of side effects. Both treatment options should be reevaluated after 3-6 weeks. Systemic or local analgesic therapy should be given simultaneously (e.g., lidocaine gel). Botulinum toxin is not approved in Switzerland for the treatment of fissures due to lack of evidence regarding efficacy as well as high price and possible side effects (painful injection, perianal vein thrombosis 5-10%, reversible incontinence 3-12% and risk of infection).

If there is no improvement in symptoms after six weeks of therapy, compliance should be inquired about or surgical treatment of the anal fissure should be considered [2]. There are several options for this, with fissurectomy being the most common. This involves debridement and removal of the papilla and guardian mariske. At best, this is combined with partial endoanal wound margin adaptation. In this case, there may be a temporary slight disturbance of fine incontinence (especially wind leakage). However, relevant fecal incontinence practically never occurs. The success rate is 80%. If the fissurectomy is unsuccessful, it can either be repeated again or, alternatively, a reconstructive procedure such as the V-Y flap can be performed. Here, the fissure is covered with a skin flap from the anal region. The success rate is 85%.

There is a high recurrence rate with all conservative treatment options. Only 40% vs. 33% of patients showed complete cure after three years in the two-arm prospective study with nitroglycerin ointment 0.2% vs. Botox, a complete cure could be demonstrated [5]. Due to the high recurrence rate, good patient education is important so that rapid treatment can be initiated in the event of a recurrence. After the acute pain has subsided, proctoscopy and, depending on age and risk situation, complete colonoscopy are always indicated.

Fistula/abscess

Anal fistulas and abscesses usually arise from superinfected anal glands and form an abnormal connection between the rectum or anal canal and the perianal skin.

Patients usually report discharge, bleeding, pain on defecation or mechanical straining, but also persistent pain, swelling, or diarrhea. Fistulas may manifest in the setting of an underlying disease such as Crohn’s disease, proctitis, or anal carcinoma [6]. The tentative diagnosis is made clinically, after visualization of a perianal opening with pus discharge at most or palpation of an induration. Furthermore, it is important to visualize the entire fistula tract by means of anorectal endosonography or MRI and to localize it anatomically precisely.

An asymptomatic fistula does not necessarily need to be treated. However, spontaneous healing of an established fistula is low. The treatment of symptomatic fistulas is surgical, which is why a prompt referral to the specialist should be made. Anal abscesses must be drained promptly. The goal of surgical therapy for fistulas is to repair the fistula tract while maintaining fecal continence. The surgical method here depends on the type of fistula, although superficial fistulas can be treated by fistulotomy. In this procedure, the fistula is split open towards the intestine while sparing the sphincter. Infected fistulas in tissue with inflammatory changes are often treated with setons. These are sutures or rubber flaps that are pulled through the fistulas to ensure a constant flow of secretions and prevent abscesses (Fig. 1 B) . This can simplify further operations as part of a two-stage procedure. Setons are usually left in place for 2-3 months, but in cases of recurrent fistulas, e.g., in the setting of Crohn’s disease, they may be the definitive treatment. Complicated fistulas can be surgically excised, followed by endoanal coverage with a mucosal flap (“mucosa advancement flap”). A relatively new procedure is the “ligation of the intersphincteric fistula tract (LIFT)” operation. In this procedure, the fistula tract is accessed through an additional intersphincteric approach and ligated. Other surgical techniques include fistulotomy with primary sphincter suture for deeper fistulas, or fistula closure using special clips. With fistula surgery, there is always a risk of sphincter injury; in addition, postoperative infections/wound healing disorders are common, which is reflected in a success rate of only 70-80% [7,8].

Perianal vein thrombosis

Perianal vein thrombosis is a visual diagnosis and is associated with anal pain and a pressure-dolent, bluish-livid lump on the anus [1]. It is provoked in particular by heavy pressing or prolonged sitting and may also occur in women peripartum or in the context of hormonal changes. Perianal vein thrombosis that persists for less than 72 h can be incised or excised under local anesthesia. However, if the thrombosis persists >72 h, treatment is conservative with stool regulation, analgesia, and flavinoids (e.g., Daflon®). They often leave a mariske, which can be surgically removed if it is bothersome.

Other causes of anal pain

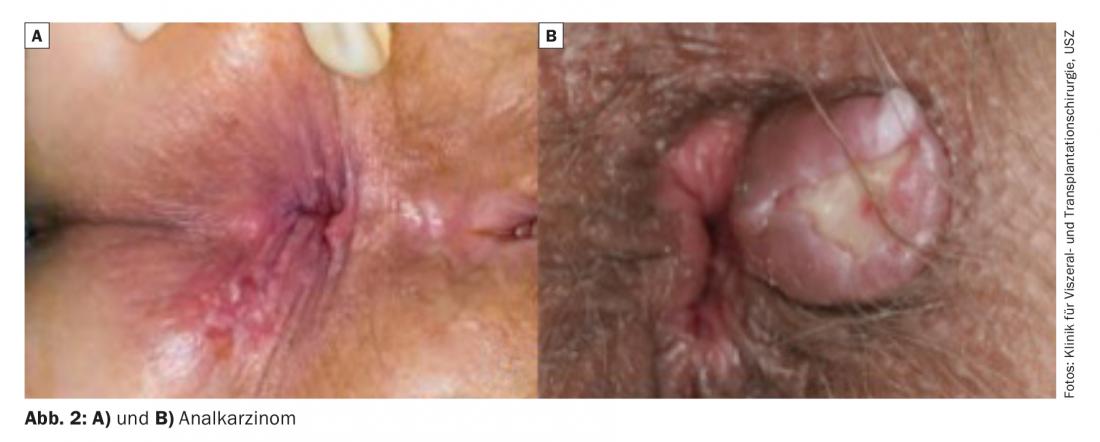

In case of anal pain, infectious proctitis should always be considered, especially since sexual risk behavior is not always obvious from the medical history. This should include a low-threshold search for gonococci, Chlamydia trachomatis (lymphogranuloma venerum) in the rectal section, and lues serology. Anal pain can also occur in anal carcinoma (Fig. 2 A and B), with perianal pain in particular indicating an advanced tumor stage [9]. Anal pain may occur as a result of ulcerative proctitis, rectal involvement in Crohn’s disease, or other systemic disease. Thus, unclear perianal pain, but also pain in the context of one of the above-mentioned differential diagnoses should be clarified low-threshold endoscopically (proctoscopy, if necessary complete colonoscopy).

Defecation pain may also be a manifestation of dyssynergic defecation disorder (anismus) and may be the only symptom reported by the patient. Rectal or anal prolapse can be objectified either during the examination or by photographs taken by the patient (Fig. 1 E and F).

Hemorrhoidal discomfort – practically always painless

Hemorrhoids are typical causes of blood discharge ab ano, foreign body sensation in the sense of prolapse during defecation, a resulting fine continence disorder with hygiene problems and perianal itching. Contrary to what many patients believe, hemorrhoidal symptoms are virtually never associated with pain.

Pain without correlate – Proctalgia fugax

Proctalgia fugax is a functional anorectal disorder that presents with severe, intermittent, self-limiting rectal pain. Between episodes lasting seconds to minutes, patients are asymptomatic. The prevalence in the general population is estimated at 4-18% [10], with only a small minority reporting the symptoms spontaneously. It occurs more frequently in women than in men. Pathophysiologically, it is thought to have a multifactorial etiology with spasm of the anal sphincter, nerve compression, neuropathy, and psychological factors [11]. Diagnosis is made after exclusion of other somatic causes using Rome IV criteria, where all criteria must be met for at least three months and symptom onset must have occurred six months earlier:

- Repeated episodes of rectal pain, which are independent of defecation.

- Episodes last seconds to minutes but no longer than 30 minutes.

- No anorectal pain between episodes.

Most patients do not need therapy due to the rarity of symptoms, and often patient education alone helps. Additionally, topical spasmolytics could be used or biofeedback therapy could be initiated.

Literature:

- Lohsiriwat V: Anorectal emergencies. World Journal of Gastroenterology. 2016; 22(26): 5867-5878.

- Nelson RL: Anal fissure (chronic). Clin Evid Handbook 2015; 145-146.

- Nelson RL, et al: A systematic review and meta-analysis of the treatment of anal fissure. Tech Coloproctol 2017; 21: 605.

- Shrivastava U, et al: A Comparison of the Effects of Diltiazem and Glyceryl Trinitrate Ointment in the Treatment of Chronic Anal Fissure: A Randomized Clinical Trial. Surg Today 2007; 37: 482.

- Sileri P, et al: Medical and surgical treatment of chronic anal fissure: A prospective study. J Gastrointest Surg 2007; 11: 1541-1548.

- Schneider MA, et al: Crohn’s disease: contemporary therapy of perianal fistulas. Schweiz Med Forum 2016; 16(42): 887-895.

- Limura E, Giordano P: Modern management of anal fistula. World Journal of Gastroenterology 2015; 21(1): 12-20.

- Bubbers EJ, Cologne KG: Management of Complex Anal Fistulas. Clinics in Colon and Rectal Surgery 2016; 29(1): 43-49.

- Sauter M, et al: Presenting symptoms predict local staging of anal cancer: a retrospective analysis of 86 patients. BMC Gastroenterol 2016; 16: 46.

- Bharucha AE, Lee TH: Anorectal and Pelvic Pain. Mayo Clinic proceedings. 2016; 91(10): 1471-1486.

- Rao SSC, et al: Anorectal Disorders. Gastroenterology 2016; 150(6): 1430-1442.e4.

HAUSARZT PRAXIS 2018; 13(6): 8-12