Early therapy is critical in principally reversible acute renal failure. In addition, prevention and adequate follow-up after hospitalization are among the cornerstones of good management in practice.

Acute renal failure (ANV) is a deterioration of renal function that occurs within hours to days and is reversible in principle. The leading symptom is a rapid rise in serum creatinine with possible onset of oliguria/anuria. In addition to the increase in urinary substances, there are also disturbances in electrolytes, acid-base balance and volume status. The extent of ANV can lead to the need for dialysis [1].

ANV occurs in up to 25% of critically ill patients and is associated with poor outcome (increased mortality, prolonged hospitalization, prolonged chronic renal failure). ANV is not only a major problem for the treating physicians in the hospital, but also poses a challenge in practice, as the primary care physician has a crucial role in the early detection and prevention of severe ANV [1].

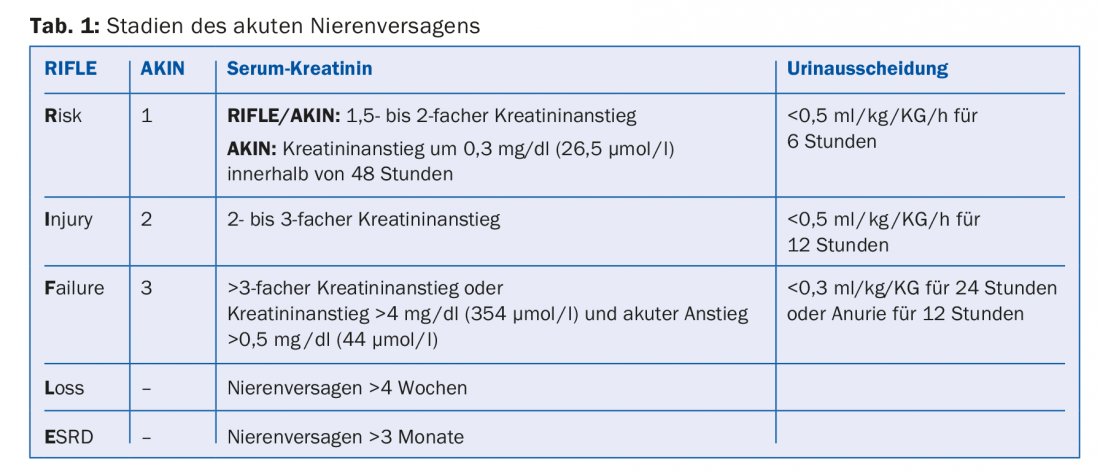

In 2004, the different definitions of ANV that existed until then were replaced by the RIFLE criteria. The acronym RIFLE stands for Risk, Injury, Failure, Loss and ESRD (end stage renal disease). In 2007, the term “acute renal failure” was abandoned in favor of the term “acute kidney injury” (AKI). In addition, the staging was adapted again (Table 1) [2].

Etiology

The causes of ANV can be divided into three groups: so-called prerenal, intrarenal, and postrenal renal failure [3]. Among these, prerenal ANV is the most common, accounting for approximately 70%.

Prerenal ANV is usually an acute condition in which hypovolemia, hypotension, or drug side effects result in decreased renal blood flow with a consecutive decrease in glomerular filtration rate and consequent increase in urea and creatinine and decrease in diuresis. Depending on the duration and severity of renal perfusion impairment, tubular necrosis may also occur [4].

Postrenal ANV is present in 5-10% of cases. This occurs when there is obstruction in the urinary tract such as upper urinary tract outflow obstruction, urinary retention in the setting of prostatic hyperplasia, or other bladder emptying disorders [4].

Renal ANV is relatively rare, with the risk of irreversible renal injury being greatest in the absence of early diagnosis. These are usually diseases of the renal vessels, glomeruli, tubules, or interstitium, such as acute glomerulonephritis, vasculitis, or interstitial nephritis, as well as renal involvement in systemic diseases [4].

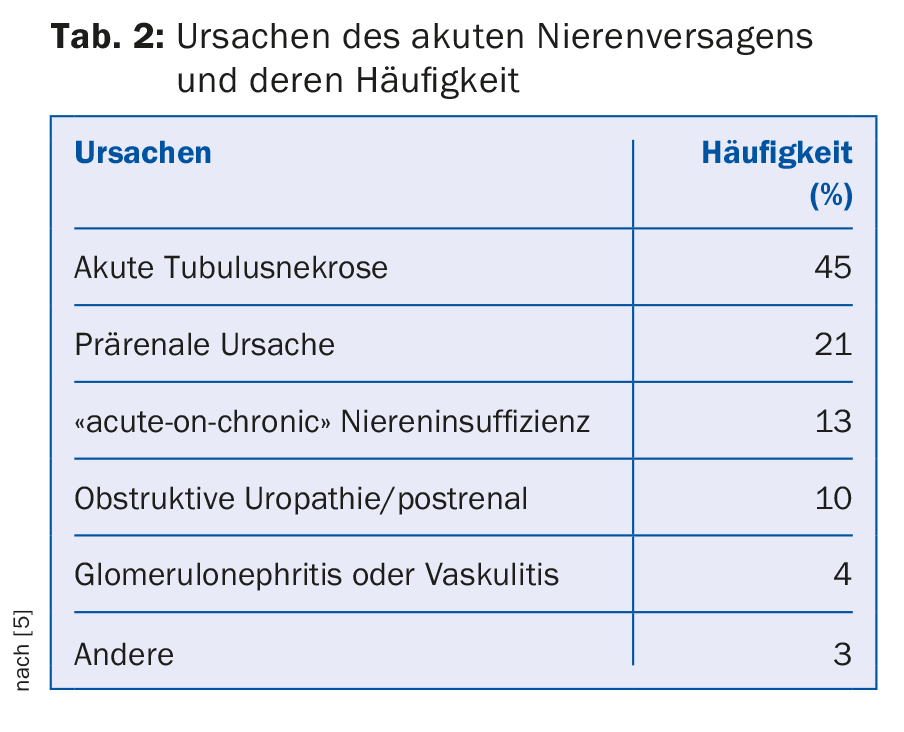

Table 2 summarizes again the causes of acute renal failure and their frequency [5].

Risk factors

Several risk factors are known to increase the likelihood of ANV occurrence. The most common risk factors include chronic pre-existing renal failure, arterial hypertension, diabetes mellitus, heart disease, liver failure, and older age. Acute risk factors include volume deficiency, marked hypotension, infection, hemolysis, rhabdomyolysis, and nephrotoxic drugs. In most cases, several risk factors are present that favor the occurrence of ANV [6,7].

Symptoms

Often, the diagnosis of renal insufficiency is an incidental finding due to elevated creatinine in a routine laboratory. In clinical practice, it is crucial to know whether the renal failure is acute or chronic in order to coordinate further investigations and therapies. Depending on the severity of acute renal failure and etiology, there are clinical symptoms suggestive of renal failure. With a prerenal etiology, there is usually hypotension, orthostasis tendency, and oliguria. With a renal cause, hypertensive blood pressure, hypervolemia with risk of pulmonary edema, pleural effusions, and peripheral edema are often present, as well as macrohematuria or frothy urine, depending on the syndrome.

Diagnostics

Once a diagnosis of ANV has been made, it is important to clarify the etiology and assess whether it is possible to continue the patient’s care in an outpatient setting. In addition to the severity of the ANV and the suspected diagnosis, the patient’s comorbidities are also critical.

Initially, it must be assessed whether the ANV can be explained in the context of the acute illness that led to the consultation (e.g., infection, cardiac decompensation, acute postrenal problem). Furthermore, the patient’s medication history should be carefully obtained to diagnose drug-induced ANV, if any, and medications should be adjusted according to the impaired renal function.

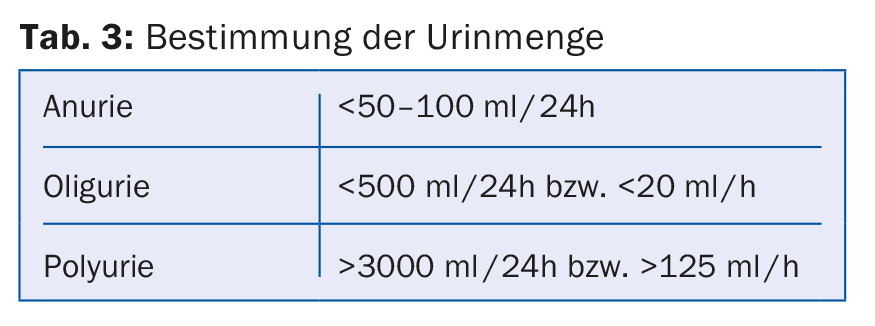

Clinical examination should look for dehydration (hypovolemia, hypotension) or signs of overhydration (leg edema, jugular veins, hypertension). Furthermore, the amount of urine per 24 hours should be asked, as acute renal failure can be anuric, oliguric, or polyuric (Table 3) [4].

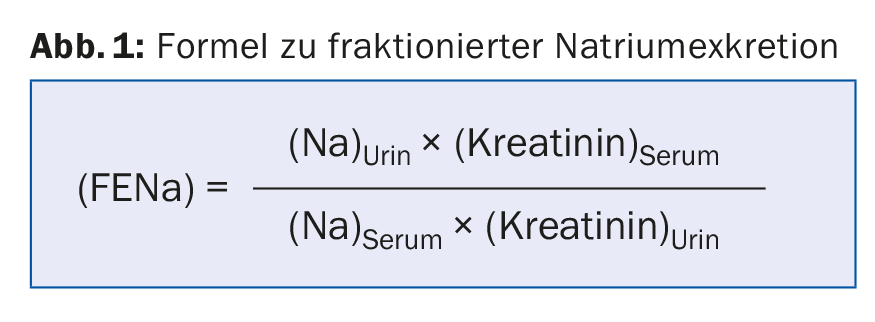

Further clarification steps include a urine status with urine sediment and a sonographic evaluation of the kidneys (exclusion of postrenal cause, indication of acute nephritis). In ANV, determination of renal indices in urine may be helpful for further differentiation regarding pre- vs. renal insufficiency. Urine sodium excretion is low in prerenal ANV because of maximal sodium reabsorption in the kidney. Fractional excretion of sodium is less than 1% in a prerenal ANV (Fig. 1) [8].

Under therapy with diuretics, fractional urea excretion should be calculated, with urea substituted for sodium in the formula. In prerenal ANV, fractional urea excretion <is 35% [9].

Therapy

The most important question with ANV in practice is whether outpatient therapy is possible and how promptly follow-up is needed. If pre- or postrenal ANV is present as part of an acute illness and there is only mild to moderate deterioration in renal function (ANV stage 1 to a maximum of 2), outpatient therapy can be provided if the patient has appropriately low comorbidities. In the most common prerenal ANV, continued volume management and improvement of renal perfusion are critical for recovery of renal function. Depending on the situation (infection, dehydration), parenteral volume substitution must be given and diuretics and antihypertensive drugs, especially ACE inhibitors and ARBs, must be paused. In addition, the dosage of all renally eliminated drugs must be adjusted. In the setting of prerenal ANV in the context of cardiac decompensation in the sense of “low output,” the focus is usually on cardiac recompensation by means of increasing diuretic therapy [10]. A clinical and laboratory follow-up should be performed after 24- 48 hours to monitor the success of therapy and readjust the medication. In postrenal ANV in the context of prostatic hypertrophy or bladder voiding dysfunction, rapid insertion of a bladder catheter with subsequent monitoring of renal function after 48 hours at the latest and further urological evaluation in the longer term is usually sufficient. In cases of upper urinary tract obstruction and urolithiasis, therapy should be discussed directly with the urologist on an interdisciplinary basis.

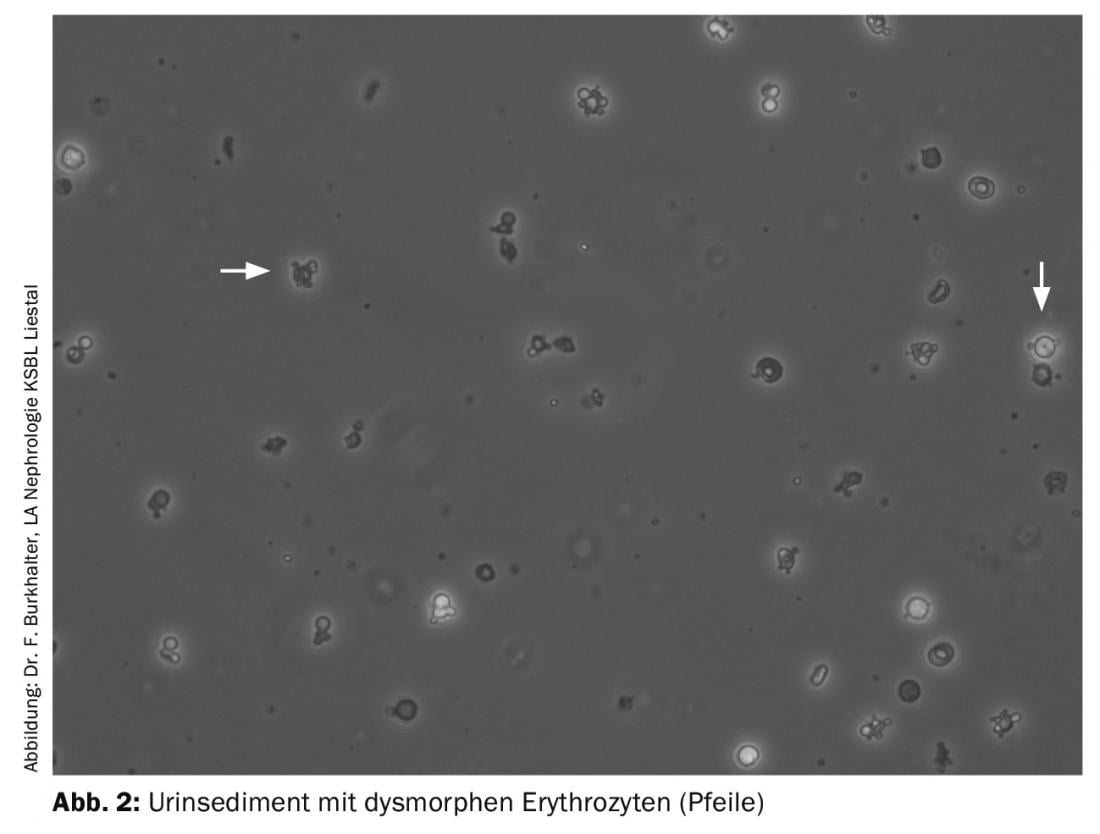

In contrast to pre- and postrenal ANV, outpatient therapy for renal ANV is rarely possible and should be done only in consultation with a nephrologist. If the urine sediment shows evidence of glomerulonephritis (microhematuria, proteinuria) (Fig. 2) or if there are clinical symptoms suggestive of inflammatory disease (vasculitic skin lesions, arthralgias, epistaxis, or hemoptysis), the patient should be rapidly presented to a nephrologist or, depending on the situation, hospitalized directly. The same is true for renal ANV with hypercalcemia. If the medical history reveals a possible ANV in the context of a nephrotoxic drug (e.g., NSAIDs, antibiotics, proton pump inhibitor, allopurinol, chemotherapy or immunotherapy), this drug must be discontinued immediately and, depending on the severity of the ANV and its course, the patient must be referred to a nephrologist for further evaluation.

In addition to proper management of ANV, prevention in practice is also important. In this context, it is important to prevent ANV in patients at increased risk of developing ANV, if possible, according to the clinical situation. As a rule, these patients should be instructed to reduce or pause certain medications (ACE inhibitors, ARBs, and diuretics) when acutely ill (so-called “sick day rules”).

Further, it is important that patients with ANV are followed up in the office after hospitalization. It should be checked whether the kidney function recovers. If renal function remains impaired, it should be monitored at two- to four-week intervals (if necessary, urine sediment and proteinuria should be determined again). If renal insufficiency persists or glomerular microhematuria is found, resp. relevant proteinuria, referral for nephrological evaluation is indicated if the situation is unclear. At the latest in the case of persistently impaired renal function three months after an ANV, chronic renal insufficiency must be assumed and correspondingly longer-term follow-up must be carried out (course of proteinuria, renal function, occurrence of secondary complications). In addition to monitoring renal function, it is important to restart or increase medications paused during hospitalization due to ANV, depending on the clinical situation.

Take-Home Messages

- Acute renal function deterioration should be taken seriously.

- A distinction is made between prerenal, renal and postrenal forms.

- Early initiation of therapy is critical in principally reversible acute renal failure.

- In addition to proper management, prevention in practice is also important. As a rule, patients at increased risk should be instructed to reduce or pause certain medications when acutely ill (so-called “sick day rules”).

- Patients with acute renal failure should be followed up in the office after hospitalization.

Literature:

- Bellomo R, et al: Acute renal failure – definition, outcome measures, animal models, fluid therapy and information technology needs: the Second International Consensus Conference of the Acute Dialysis Quality Initiative (ADQI) Group. Crit Care 2004; 8(4): R204-212.

- Mehta RL, et al: Acute Kidney Injury Network: report of an initiative to improve outcomes in acute kidney injury. Crit Care 2007; 11(2): R31.

- Lameire N, Van Biesen W, Vanholder R: Acute renal failure. Lancet 2005; 365(9457): 417-430.

- Rahman M, Shad F, Smith MC: Acute kidney injury: a guide to diagnosis and management. Am Fam Physician 2012; 86(7): 631-639.

- Liano G, Pascual J: Acute renal failure. Madrid Acute Renal Failure Study Group. Lancet 1996; 347(8999): 479; author reply 479.

- Whelton A: Nephrotoxicity of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs: physiologic foundations and clinical implications. Am J Med 1999; 106(5B): 13S-24S.

- Nash K, Hafeez A, Hou S: Hospital-acquired renal insufficiency. Am J Kidney Dis 2002; 39(5): 930-936.

- Miller TR, et al: Urinary diagnostic indices in acute renal failure: a prospective study. Ann Intern Med 1978; 89(1): 47-50.

- Carvounis CP, Nisar S, Guro-Razuman S: Significance of the fractional excretion of urea in the differential diagnosis of acute renal failure. Kidney Int 2002; 62(6): 2223-2229.

- Verbrugge FH, Grieten L, Mullens W: Management of the cardiorenal syndrome in decompensated heart failure. Cardiorenal Med 2014; 4: 176-188.

HAUSARZT PRAXIS 2018; 13(4): 32-35