Family physicians are increasingly confronted with incidental findings of benign liver tumors due to modern imaging. In many cases, referral to a specialist team is required. Today, operations can usually be performed laparoscopically.

Patients with abdominal symptoms are often diagnosed with incidental findings in the liver on imaging. Most often, these are cysts or hemangiomas, benign liver lesions. It is important to know when further clarification is needed. Due to the size or growth of these lesions, certain tumors can lead to bleeding or even malignant degeneration.

In case of pain in the right upper abdomen, an ultrasound examination of the gallbladder and biliary ducts and the exclusion of a malignancy should be performed. In the case of simple cysts and hemangiomas, the diagnosis can be made by ultrasound. Focal nodular hyperplasia (FNH), adenomas, or complex cysts require further imaging, nowadays directly with MRI (no CT needed anymore). In MR imaging, the administration of liver-specific contrast agent is important because it allows reliable diagnosis even without biopsy. Surgical indications include symptoms, complications such as bleeding or malignant transformation, and, in rare cases, diagnostic uncertainty.

Hemangiomas: Easy to diagnose, rarely problems

Hemangiomas are the most common benign tumors of the liver, accounting for 70%, and occur in one-third of the population, more often in women than in men (5:1). They are mostly solitary. In up to 40% of patients, there are multiple hemangiomas, often in the same liver segment. The hemangioma is surrounded by a pseudocapsule. It arises from endothelial cells and is a vascular tumor. Hemangiomas can change in size. The larger a hemangioma, the more often it has thrombosis, necrotic areas, or calcifications. Hemangiomas >10 cm are giant hemangiomas.

In most cases, hemangiomas remain asymptomatic. Symptoms occur when they increase in size in a displacing or compressing manner (e.g., upper abdominal pressure sensation and anorexia due to gastric compression). Within the liver, they can cause cholestasis or vascular obstruction. Spontaneous rupture is extremely rare and unlikely if the size is normal. It actually occurs only in large exophytic hemangiomas (rare isolated cases).

Ultrasound is sufficient for diagnosis in most cases. A hyperechogenic mass with specific perfusion from the outside to the inside is seen. In larger findings, calcifications or thromboses are visible. In unclear cases, specialists can use contrast-enhanced ultrasound to confirm the diagnosis. Biopsy or puncture should be avoided because of the risk of bleeding.

In small findings (<5 cm) and asymptomatic patients no follow-up and therapy are necessary. In exophytic findings >5 cm, without indication for surgery, close monitoring after six months is indicated to be sure that the hemangioma remains stable in size. After that, no further control is necessary. Because of the low risk of rupture, it is not necessary to avoid contact or extreme sports. Abortion is also not justified.

Symptomatic patients should be referred to a liver surgeon to determine the indication for surgery. Radiological interventional embolizations or radiofrequency ablations are of short success. Drug therapy or radiation are out of the question. Surgical approaches include open enucleation (excision including capsule without liver tissue) or laparoscopic anatomic liver resection.

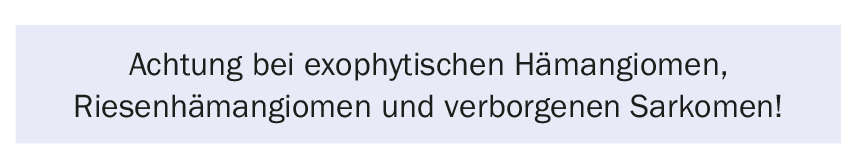

If there is weight loss, back pain, rapid growth, atypical pooling, or calcifications, further evaluation with MRI and biopsy must be performed to rule out hemangiosarcoma or hemangioendothelioma (Fig. 1).

A special form of giant hemangioma is Kasabach-Merritt syndrome, which is associated with disseminated intravascular coagulation and thrombocytopenia. Kasabach-Merritt hemangiomas require surgical removal.

Focal nodular hyperplasia: the good tumor

At 15%, the second most common tumor is FNH, a lobulated tumor with a central scar and fibrous septa. There is no capsule, but there is a sharp demarcation from the surrounding liver parenchyma. Imaging reveals a prominent feeding artery that gives off radial branches (wheel spoke phenomenon on ultrasound). In 80% solitary findings with diameters up to 5 cm are present. In 3%, diameters of >10 cm are also described. FNH occurs more frequently in middle-aged women. A connection or influence with contraceptives is not certain and we do not recommend women to stop taking the pill. The gender ratio of women to men is 8:1.

FNH is usually asymptomatic. Symptoms do not appear until there is a mass effect of the surrounding structures. Spontaneous ruptures are even less likely than in hemangioma. There are no transformations to malignant degeneration. FNH can be well identified sonographically (wheel spoke phenomenon). If uncertain, MRI should be performed, which is diagnostic in more than 95%. Biopsies are not necessary. If symptoms are present, (laparoscopic) resection is reasonable. Otherwise, similar to hemangioma, it can be waited and only followed up sonographically to ensure the stability of the finding (e.g., after six months). Further controls are not necessary. Complications such as rupture or hemorrhage are extremely rare and raise the question of whether it is not an adenoma after all.

Hepatocellular adenoma: a potentially dangerous liver tumor

Hepatocellular adenoma is a very rare (<5%) benign neoplasm of the liver. Due to the risk of bleeding and degeneration, it is the most dangerous entity. Young women of childbearing age are often affected, but also patients with glycogen storage diseases and men taking anabolic steroids. There is an established association between intake of sex hormones and development of adenomas.

Macroscopically, there is a well-circumscribed mass with a pseudocapsule, without Kupffer cells or biliary epithelial cells. 80% of all adenomas are solitary. The presence of multiple adenomas (>10) is referred to as adenomatosis. Most affected individuals are asymptomatic. Size-related symptoms include fever and abdominal (upper abdominal) pain. Large tumors (>5 cm) have a 40% risk of rupture. Pregnancy may also pose a risk of rupture.

Hepatocellular adenomas are a precancerous condition, similar to polyps in the colon. The risk of malignant degeneration exists in 4-5%. Risk factors include tumor size of >5 cm, male gender, and use of androgens.

MRI with liver-specific contrast agent is necessary to confirm the diagnosis. In adenomas without clear surgical indication, biopsy is indicated to confirm the “subtype”. Certain subtypes have a greater risk of degeneration than others. However, biopsies should be performed only in liver centers, because immediate selective embolization may be necessary if bleeding occurs.

Among the subtypes, inflammatory adenoma (IHCA) is particularly noteworthy. Caution must be exercised, as this is where the greatest potential for transformation to hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) exists.

Overall, adenoma size, gender, and subtype are critical for therapy selection. Therefore, referral to the surgeon should be made. Men are generally recommended for resection because of the risk of malignant transformation, regardless of size and subtype.

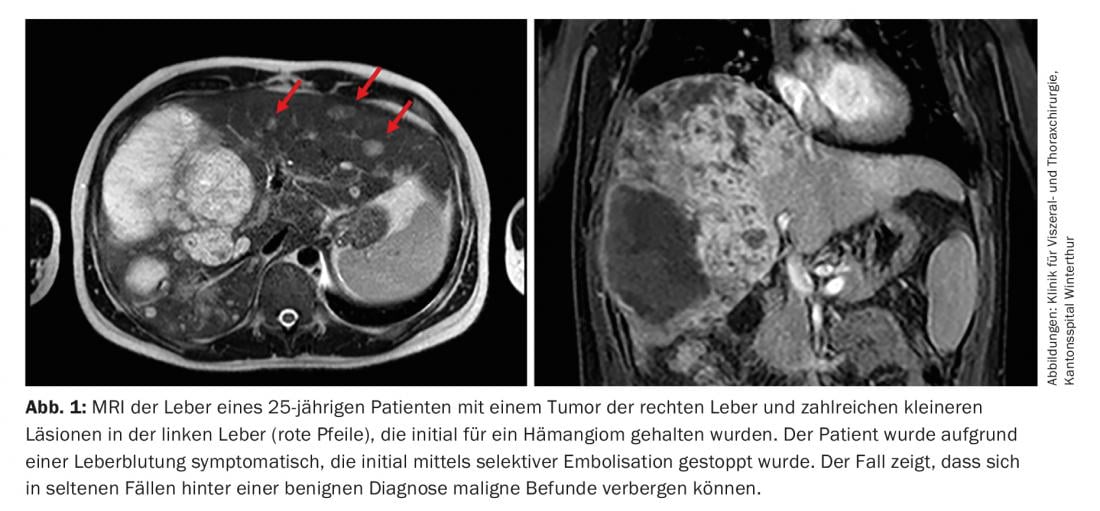

Women should stop taking contraceptives. For small adenomas (<5 cm), either follow-up with MRI or biopsy may be considered. In the case of a size of >5 cm, inflammatory adenomas and in women of childbearing potential, resection should be performed, which is almost always possible laparoscopically (Fig. 2) . In patients with no indication for surgery, radiofrequency ablation can be performed. Disadvantage here: No histology is available at the end.

Cysts: Mostly harmless, except for complex cysts

Liver cysts have a prevalence of 2-7%. They are divided into congenital (dysontogenic) and acquired (traumatic or parasitic) cysts. Congenital “simple” cysts are the most common. They are usually asymptomatic. Liver cysts are diagnosed more frequently in women (9:1) and in the right lobe of the liver. The gold standard of classification is sonography. If complex (septated or chambered) cysts are present, MRI should always be performed.

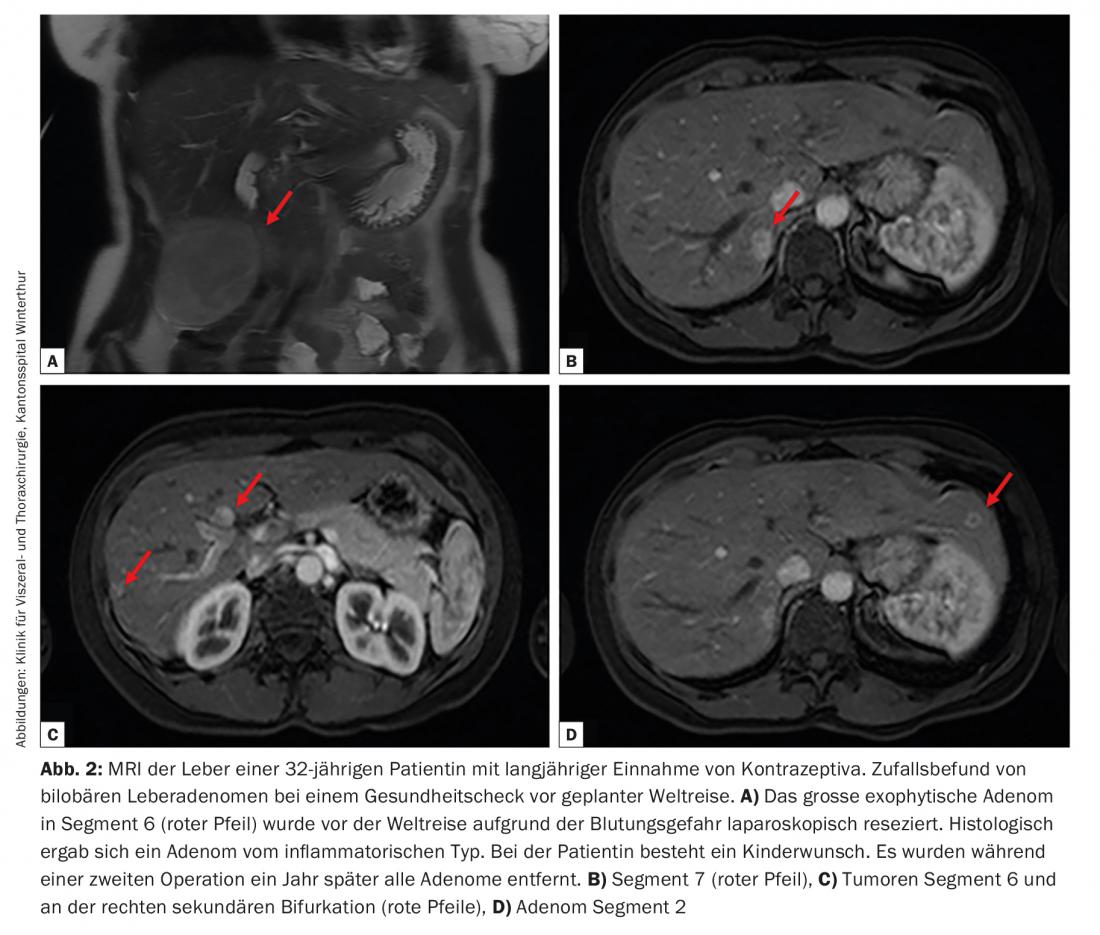

As the size increases, symptoms may occur (pain, fever, jaundice). Symptomatic or rapidly growing cysts should be surgically fenestrated, laparoscopically if possible ( Fig. 3).

In renal and hepatic cyst disease, there is often a completely remodeled cystic liver. In rare cases, rarification of the liver parenchyma and hepatic decompensation occur during the course of the disease. Such patients need to be seen by hepatologists and evaluated regarding transplantation at a university center.

Switzerland is an endemic area for echinococcosis of the liver. The most common pathogens are canine (Echinococcus granulosus cysticus) and fox (Echinococcus multilocularis alveolaris) tapeworm. Cystic echinococcosis (dog tapeworm) affects the liver more often than other organs, accounting for two-thirds of all cases. Humans are intermediate hosts, infection occurs unnoticed, often in childhood. Imaging shows a cystic formation with membranous internal structure, the typical hydatidic sand (scolizes) and partial calcification. Pathognomonic imaging must be supplemented by serologic testing (ELISA). Puncture is prohibited due to anaphylactic reactions and spread of the scolices. Patients should be referred to hepatologists and liver surgeons if suspected. Therapy of choice, after antihelmintic pretreatment with albendazole, is complete anatomic resection, without opening the cyst, and removal in toto. If complete removal is not possible, controlled opening and flushing of the cyst with echinococcal toxic substances is possible.

Alveolar echinococcosis is considered equivalent to malignant disease because without therapy the majority of patients die within ten years of symptom onset. These patients should be treated perioperatively with albendazole and resected anatomically. In rare cases, multivisceral and pulmonary resections and sometimes even liver transplants are necessary.

Simple liver cysts can be diagnosed by ultrasound in the primary care physician’s office and followed up until the finding is stable, after which no follow-up is necessary. Complex cysts always require further imaging (MRI) and referral to a specialist.

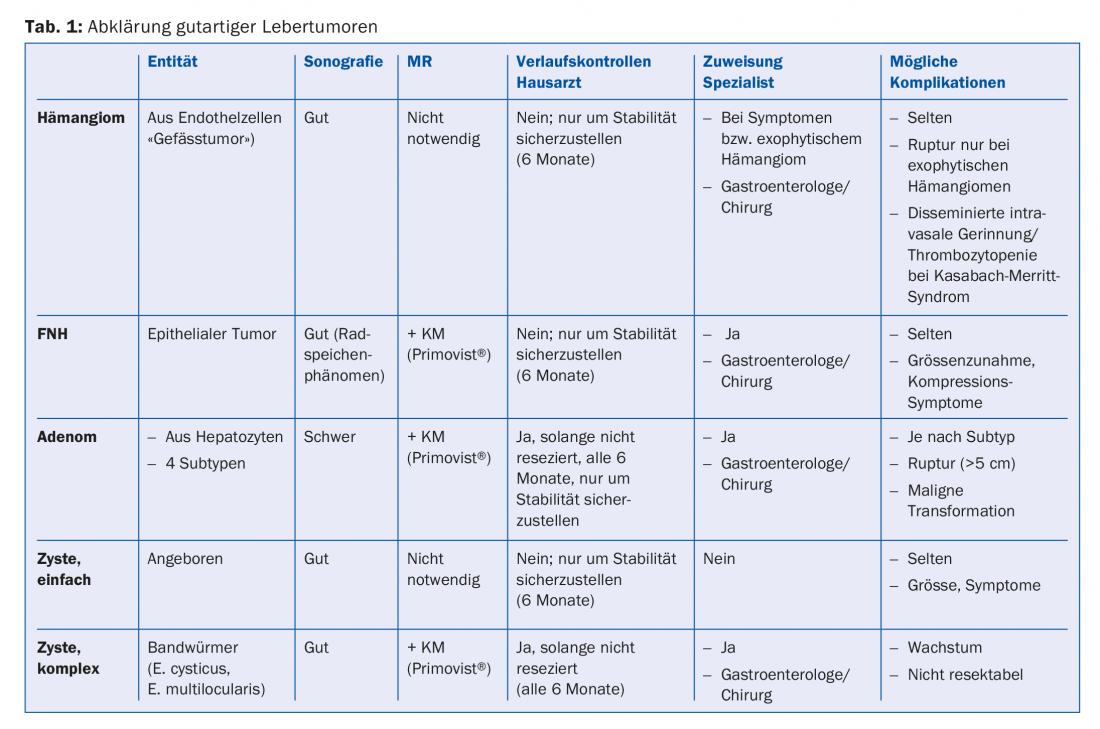

A summary and overview of the workup for benign liver tumors is provided in Table 1.

Take-Home Messages

- Due to modern imaging, primary care providers are increasingly confronted with incidental findings of benign liver tumors.

- Diagnosis can be made and monitored sonographically for cysts and hemangiomas. In focal nodular hyperplasia (FNH) and hepatocellular adenomas, as well as the complex hepatic cysts, MRI examination with liver-specific contrast medium is necessary for differentiation.

- Subsequently, referral to a specialist team (gastroenterologist and surgeon) should be made in any case in order to offer the patient a good therapy concept.

- Surgery is indicated in symptomatic patients, certain patients with hepatocellular adenomas, patients with alveolar echinococcus cysts, and those in whom there is diagnostic uncertainty. Nowadays, operations can almost always be performed laparoscopically.

Further reading:

- Wanless IR: Benign liver tumors. Clin Liver Dis 2002; 6(2): 513-526.

- Belghiti J, et al: Diagnosis and management of solid benign liver lesions. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 2014; 11(12): 737-749.

- Grazioli L, et al: Primary benign liver lesions. Eur J Radiol 2017; 95: 378-398.

- Abdelrahman K, et al: Benign focal liver lesions: a clinical, radiological and pathological review. Rev Med Suisse 2017; 13(572): 1474-1479.

- de Reuver P, et al: Long-term outcomes and quality of life after surgical or conservative treatment of benign simple liver cysts. Surg Endosc 2017. DOI: 10.1007/s00464-017-5645-3 [Epub ahead of print].

- Toro A, et al: What is changing in indications and treatment of hepatic hemangiomas. A review. Ann Hepatol 2014; 13(4): 327-339.

- Hussain SM, et al: Focal nodular hyperplasia: findings at state-of-the-art MR imaging, US, CT, and pathologic analysis. Radiographics 2004; 24(1): 3-17; discussion 18-19.

- Stoot JH, et al: Malignant transformation of hepatocellular adenomas into hepatocellular carcinomas: a systematic review including more than 1600 adenoma cases. HPB (Oxford) 2010; 12(8): 509-522.

- Ronot M, et al: Hepatocellular adenomas: accuracy of magnetic resonance imaging and liver biopsy in subtype classification. Hepatology 2011; 53(4): 1182-1191.

- Kern P, et al: The Echinococcoses: Diagnosis, Cinical Management and Burden of Disease. Adv Parasiol 2017; 96: 259-269.

HAUSARZT PRAXIS 2018; 13(1): 9-13