Most bladder cancers are non-muscle invasive, so the bladder can be preserved. Because of the risk of recurrence, invasive tumor follow-up is required for years. After cystectomy with urinary diversion, renal function and hypovitaminosis (folic acid, vitamin B12) should be monitored in the long-term course. The most important modifiable risk factor of bladder cancer is smoking; patients should be helped to stop smoking. In metastatic bladder cancer, palliation is usually the only option – hope is offered by the new immune checkpoint inhibitors.

Most malignant tumors of the urinary bladder in our latitudes are classic urothelial carcinomas. Less common are squamous cell carcinomas or rarities such as adenocarcinomas arising from the urachus. Bladder carcinoma is not a common tumor, but it is not rare either; the incidence per 100,000 person-years in Switzerland is 17 in men and 4 in women (850 new cases annually in men, 270 in women). This has sometimes led to little attention being paid to this type of cancer in recent years. As a result, no truly new therapeutic strategy, whether surgical, radiooncologic, or drug, has found its way into the clinic in the last 20 years. Incidentally, the fact that smoking is the main risk factor for urothelial carcinoma is unknown to most patients and smokers [1].

Urothelial carcinomas have a high tendency for recurrence after surgical resection, resulting in extensive and invasive follow-up. Cost calculations have shown that bladder cancer results in the highest treatment costs per patient of all cancers in Europe and North America [2]. Better education of patients, especially smokers, and more investment in research are needed to ensure that this expensive, debilitating and life-threatening disease occurs less frequently in the future.

Therapy of non-muscle-invasive bladder carcinoma

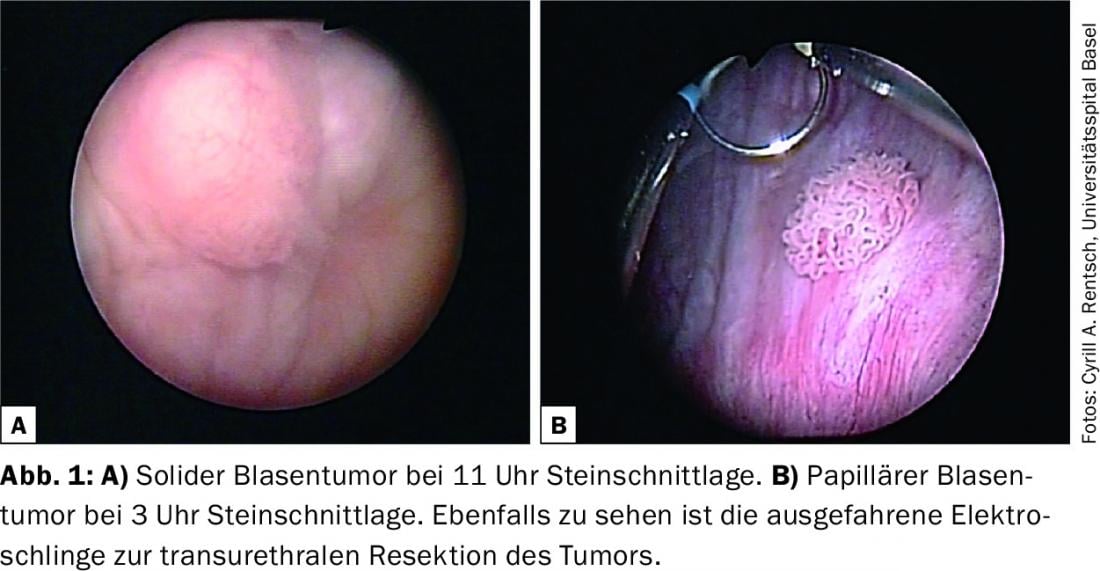

Non-muscle invasive bladder carcinomas (NMIBC) include carcinoma in situ and papillary and solid urothelial carcinomas confined to the bladder mucosa. Approximately three quarters of tumors are NMIBC at the time of diagnosis. The primary therapeutic goal in NMIBC is to preserve the urinary bladder. For this purpose, tumors are resected by transurethral resection (TUR) for diagnosis and therapy (Fig. 1) . After 2-6 weeks, most histologically non-muscle-invasive tumors undergo a post-resection to confirm complete resection and lack of bladder muscle invasion.

Instillation of an intravesical chemotherapeutic agent, performed within the first hours after TUR, can reduce the 5-year recurrence rate of well- to moderately-differentiated papillary tumors by 14% (from 59 to 45%) [3]. Patients with poorly differentiated tumors or carcinoma in situ require more intensive and prolonged adjuvant therapies. Repetitive intravesical chemotherapy achieves good results here, but is inferior to intravesical immunotherapy with the live tuberculosis vaccine BCG (Bacillus Calmette Guérin). Activation of the immune system by BCG is initially accomplished with instillations performed six times at weekly intervals, followed by maintenance therapy for at least one year. BCG therapy can reduce the risk of recurrence by 32% and the risk of progression by 27%, making it one of the most successful immunotherapies used in the clinic [4]. In carcinoma in situ, BCG therapy is the most effective method to save the patient from cystectomy.

In poorly differentiated tumors, follow-up is usually required for life because of the risk of recurrence and progression. The appropriate methods are outpatient flexible cystoscopy, urinary bladder lavage cytology, and annual upper urinary tract checks with excretory computed tomography [4].

Therapy of muscle-invasive carcinoma of the urinary bladder

In cases of proven invasion of the bladder muscles by urothelial carcinoma (muscle-invasive bladder carcinoma, MIBK), there is an indication for radical bladder excision with simultaneous pelvic lymphadenectomy. In men, this surgery includes removal of the prostate and seminal vesicles; in women, it includes removal of the uterus and vaginal anterior wall. Neoadjuvant cisplatin-containing chemotherapy is usually recommended prior to surgery if the patient’s general condition permits. With this, an improvement in overall survival from 45 to 50% can be achieved [5]. For adjuvant chemotherapy, the data are clearly positive only with regard to progression-free survival – for overall survival, the data are still unclear [6].

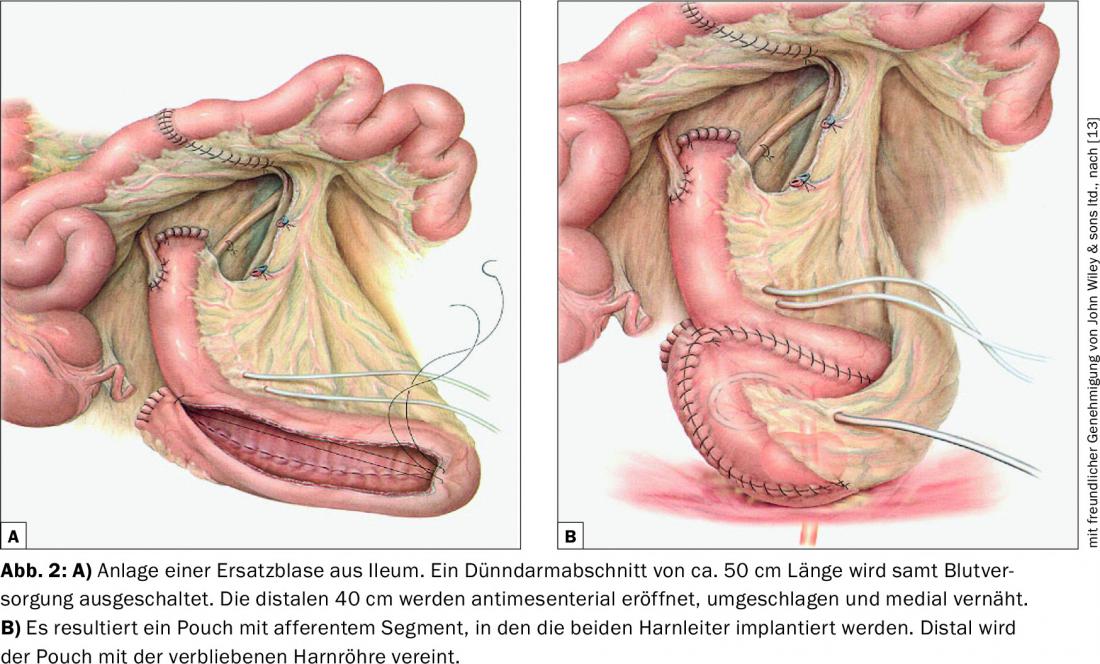

When draining urine after bladder removal, a basic distinction is made between continent and incontinent procedures. Various sections of the gastrointestinal tract can be considered as a drain, although the distal ileum or ileocoecal region have become established here. The most widely used incontinent urinary diversion procedure worldwide is the ileum conduit. The ileal replacement bladder according to Studer has become established in Switzerland as a continent and orthotopic replacement bladder procedure (Fig. 2). The resorption of urine components by the respective ileal intestinal segment used results in metabolic acidosis, which may have to be corrected. Since part of the distal ileum is involved, vitamin B12 and folic acid must be monitored regularly and substituted if necessary. Due to the disruption of enterohepatic circulation by the eliminated ileum section, affected patients are also more likely to have calcium oxalate kidney stones. Regular monitoring of renal function is very important, especially early diagnosis and treatment of postrenal renal afflictions and optimization of internal risk factors for renal insufficiency.

As an alternative to surgery, chemoradiotherapy is available for curative treatment of carcinoma in selected situations [7]. Comparative studies between these two curative treatment modalities do not exist. The 5-year survival in MIBK has remained unchanged at approximately 50% for decades [8]. Here, advanced therapeutic approaches are required to improve the prognosis of patients.

Therapy of metastatic bladder carcinoma

Therapy for metastatic urothelial carcinoma is usually palliative in nature and consists of palliative surgical local measures (palliative TUR of the bladder, palliative cystectomy), hemostyptic (hemostatic) radiation, radiation of metastases, and palliative chemotherapy. Hope for patients with progressive tumor disease after chemotherapy lies in the new immune checkpoint inhibitors anti-PD1 and anti-PDL1, which have achieved remarkable response rates in phase I trials and even led to complete remissions in individual cases [9,10]. Future studies will show whether these promising results can be confirmed in larger patient groups.

Prevention and risk factors

Several factors increase the risk of bladder cancer. The most important risk factor is smoking. Numerous studies have shown that smokers (both cigarette smokers and pipe smokers) have about three times the risk of bladder cancer as nonsmokers. About half of all bladder cancer patients are thought to have tumors caused by smoking.

Therefore, the most important measure in the prevention of bladder cancer is to stop smoking. Recommending and actively supporting smoking cessation is also critical in relapse prevention for active smokers. Prospective studies on the impact of smoking cessation on oncologic outcomes are lacking to date. Retrospective studies have shown that smoking cessation in patients who had bladder cancer reduced the risk of recurrence by about 40% after ten years [11]. Various organizations, many hospitals, as well as the Swiss Lung League, in cooperation with the cantonal lung leagues, offer appropriate stop-smoking programs. In addition, physicians’ awareness of this important modifiable risk factor must also be raised. For example, according to a US study, only 20% of all urologists always informed smokers with bladder cancer about the need to stop smoking [12].

Other aspects of prevention primarily concern occupational exposure to chemicals. There are about 50 known chemicals that promote the development of bladder cancer. Thanks to modern occupational safety, there is hardly any contact with most carcinogenic substances today. However, decades often elapse between exposure and onset of disease, so even today, individuals with previous occupational exposure may be at increased risk.

Other risk factors for developing bladder cancer include radiation to the lesser pelvis and chronic urinary tract infections. However, in the latter, squamous cell carcinoma of the urinary bladder usually develops.

Literature:

- Westhoff E, et al: Low awareness of risk factors among bladder cancer survivors: New evidence and a literature overview. Eur J Cancer 2016; 60: 136-145.

- Sievert KD, et al: Economic aspects of bladder cancer: what are the benefits and costs? World J Urol 2009; 27: 295-300.

- Sylvester RJ, et al: Systematic Review and Individual Patient Data Meta-analysis of Randomized Trials Comparing a Single Immediate Instillation of Chemotherapy After Transurethral Resection with Transurethral Resection Alone in Patients with Stage pTa-pT1 Urothelial Carcinoma of the Bladder: Which Patients Benefit from the Instillation? Eur Urol 2016; 69: 231-244.

- Babjuk M, et al: EAU guidelines on non-muscle-invasive urothelial carcinoma of the bladder: update 2013. Eur Urol 2013; 64: 639-653.

- Witjes JA, et al: EAU guidelines on muscle-invasive and metastatic bladder cancer: summary of the 2013 guidelines. Eur Urol 2014; 65: 778-792.

- Sternberg CN, et al: Immediate versus deferred chemotherapy after radical cystectomy in patients with pT3-pT4 or N+ M0 urothelial carcinoma of the bladder (EORTC 30994): an intergroup, open-label, randomised phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol 2015; 16: 76-86.

- James ND, et al: Radiotherapy with or without chemotherapy in muscle-invasive bladder cancer. N Engl J Med 2012; 366: 1477-1488.

- Zehnder P, et al: Unaltered oncological outcomes of radical cystectomy with extended lymphadenectomy over three decades. BJU Int 2013; 112: E51-58.

- Elizabeth R, et al: Pembrolizumab (MK-3475) for advanced urothelial cancer: updated results and biomarker analysis from KEYNOTE-012. J Clin Oncol 2015; 33 (suppl; abstract 4502).

- Petrylak DP, et al: A phase Ia study of MPDL3280A (anti-PDL1): Updated response and survival data in urothelial bladder cancer (UBC). J Clin Oncol; 2015; 33 (suppl; abstract 4501).

- Rink M, et al: Impact of smoking and smoking cessation on oncologic outcomes in primary non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer. Eur Urol 2013; 63: 724-732.

- Bjurlin MA, et al: Smoking cessation assistance for patients with bladder cancer: a national survey of American urologists. J Urol 2010; 184: 1901-1906.

- Studer UE, et al: Orthotopic ileal neobladder. BJU Int 2004; 93(1): 183-193.

InFo ONCOLOGY & HEMATOLOGY 2016; 4(5): 18-21.