CARDIOVASC interviewed PD Dr. med. Dr. Daniel Barthelmes, Senior Physician at the Eye Clinic at the University Hospital Zurich, on the topic of diabetic eye diseases. The focus was on the risk of such complications, early detection and diagnostic control. How can the different stages of diabetic retinopathy and macular edema be treated, and when is which procedure used? Are there therapeutic innovations that will keep us busy in the coming years? Collaboration between the different disciplines was also addressed.

Dr. Barthelmes, how many diabetics are affected by eye damage in the course of their disease?

PD Dr. Barthelmes:

The eye, especially the retina at the back of the eye, is the organ that is affected first by diabetic damage and also most frequently. A diabetic’s risk of developing associated eye disease is very high.

However, it is a complication that develops over time and sometimes takes years to manifest [1]. In young patients with type 1 diabetes, about 86% have diabetic retinal disease after 15 years. Of course, the extent of this damage varies considerably between individuals.

Are there certain risk groups among diabetics who are particularly at risk for early and pronounced eye damage?

Known and well-studied risk factors are the level of blood sugar and blood pressure. Patients with too high blood sugar over a long period of time develop pronounced eye damage very early. The better and earlier the blood sugar is controlled, the slower the progression and the less pronounced the damage is at the beginning. Individuals with high blood pressure experience additional acceleration. But even if you control both factors very well, you will eventually see changes in the back of the eye.

What can be noted is that type 1 diabetics are often diagnosed with diabetes at a young age because these patients are symptomatic early (e.g., weight loss, frequent urination, etc.). Changes in the ocular fundus are rare in this group at the time of diabetes diagnosis (approximately 6%) because of the short time between establishment of diabetes and diagnosis.

Type 2 diabetes, on the other hand, can build up over several years, resulting in more than one-third of patients already having changes in the back of the eye at the time of diagnosis [1,2].

How does diabetic retinopathy announce itself, what should the primary care provider look for? And when should he refer the patient to the specialist?

Once the diagnosis of diabetes is made, a referral to the ophthalmologist should also be initiated. Thereafter, the changes in the eye are examined at regular intervals. The problem is that when diabetes has not yet been diagnosed, there are otherwise no clear red flags that clearly indicate diabetic retinopathy. In any case, a patient with visual deterioration should be referred, which is obvious and usually happens. It may be that the damage is then already very advanced or still relatively treatable. There is no such thing as a score that dictates when to refer a patient with eye problems suspected of diabetic retinopathy to an ophthalmologist. This is also the reason why patients diagnosed with diabetes must be followed up regularly – the assessment is done by an ophthalmologist.

Overall, visual impairments in diabetic eye damage are nonspecific, inhomogeneous, and can span the spectrum from seeing through a fog to reducing vision to light-dark differences. The indication of such changes alone, without measurement of blood glucose, cannot yet diagnose diabetic retinopathy at the general practitioner.

What are the ophthalmic examination intervals for diabetics with regard to the prevention or control of eye damage?

As mentioned above, ophthalmologic control is indicated in all patients diagnosed with diabetes. It is therefore part of the basic clarification. Recommendations regarding further control and therapy are then based on the present stage or severity of ocular damage. It is divided into mild, moderate and severe non-proliferative diabetic retinopathy (NPDR) and proliferative form (PDR). For example, if there is mild NPDR, i.e. the initial stage, and well-controlled blood glucose, a control interval of about one year is sufficient. In the case of very advanced diabetes and more severe eye damage, a monthly check-up may be necessary, although this is rare in this country – unless there is a treatment plan that requires a monthly visit. In high-risk patients who do not yet require therapy, intervals of approximately three months are common.

What applies to pregnant patients and to diabetics who want to become pregnant?

Diabetic women of childbearing age should be adjusted as well as possible before pregnancy and necessary treatments should also be performed on the eye. This requires some planning of the pregnancy – if this is possible. In patients who develop gestational diabetes, there is usually no eye damage yet, so there is no need to treat the eye. During pregnancy, the aim is to act via the systemic therapy track, i.e. to control diabetes (and blood pressure) as well as possible. Fortunately, ophthalmologic treatment is very rarely required during pregnancy.

How often does the nonproliferative transition to the proliferative form of retinopathy? When is clinically significant macular edema imminent?

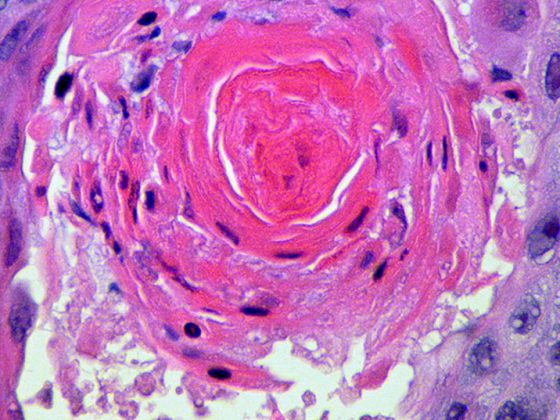

NPDR primarily involves changes in the small blood vessels, which may form microaneurysms or leak, meaning that the vessel wall is no longer tight and fluid leaks from the blood vessel into the nerve tissue. There may also be hemorrhages into the retina or – and this is where the transition to the proliferative stage comes in – the formation of new blood vessels at the back of the eye, the neovascularizations. These in turn can cause severe bleeding into the interior of the eye.

Up to one-third of patients develop PDR, which, if left untreated, results in blindness in the majority of cases [1,2]. Today, we have well effective antidiabetic drugs available that effectively control diabetes, therefore such negative consequences have become rare.

Macular edema is a separate entity that can be added to the peripheral changes mentioned above. Sometimes it occurs when the patient already has severe proliferations, sometimes already low-grade changes at the back of the eye like single small microaneurysms are accompanied by macular edema. Exactly when macular edema occurs is not yet fully understood. Type 1 diabetics tend to be affected somewhat less frequently than type 2 diabetics. However, there are no specific risk factors.

Peripheral disease with neovascularization is associated with a very high risk of total blindness. In contrast, macular edema does not lead to blindness in the sense of a complete loss of vision. Although the patient experiences a reduction in visual acuity, the eye as an organ continues to function in and of itself.

What ophthalmic therapies are currently available in diabetic retinopathy or macular edema? What are the goals of the treatment?

Today, if a patient has neovascularization, laser treatment of the back of the eye is still the first-line therapy. If there is concomitant macular edema, this is also treated, usually with VEGF inhibitors. If the person has neither neovascularization nor macular edema, one does not perform any therapy and controls clinically. Thus, therapy is only given if damage in the form of neovascularization or macular edema is already present. “Prophylactic” laser treatment of all affected individuals to prevent proliferation does not work [3]. The ophthalmological control serves to discover the respective changes so that targeted treatment can be given.

Re-progression cannot be completely prevented or ruled out with treatment. The problem with diabetes is that the disease damages the capillaries. As long as you have the diabetes, the damage to these small vessels goes on and on. The treatment of the eye, i.e. peripheral neovascularization or macular edema, is not a therapy of the microangiopathy per se, which is the actual cause of the retinal disease, but a fight against the damage that has already occurred or the secondary complications. To date, there is no therapy for microangiopathy itself.

What are the possibilities of laser therapy and when is it used?

Here we must distinguish between peripheral and macular laser therapy. The former – called panretinal laser coagulation – coagulates the tissue at the back of the eye with a kind of small “welding spots.” What happens after that is still unclear. It is assumed that less VEGF is produced in the eye after laser treatment. The retinal neovascularizations regress and long-term stabilization of vision and preservation of the eye can be achieved. About three to five sessions are required, followed by regular re-evaluations and follow-up visits, initially every two to three months, then every six months or annually if stable. In most patients this works well, but neovascularizations may recur, for example, in poorly controlled diabetics or long courses, or may not yet have been adequately treated and require follow-up. As mentioned, progression cannot be excluded with certainty.

In the past, macular edema was more frequently treated by laser than today, when we have good drug therapies available. Compared to the peripheral variant, the laser treatment is performed on a smaller scale and with little energy. The mechanism here is probably different, since the laser foci are so small that a strong reduction of VEGF cannot be assumed. However, the mechanism has not been fully researched. It has been shown that due to laser treatment the expression of certain proteins in the eye changes and there is an improvement of the blood-retinal barrier. The vessels are “sealed” – but not by the laser, but by metabolic changes that occur in the retina. The laser preserves vision and prevents deterioration.

How do VEGF inhibitors work?

VEGF inhibitors are first-line therapy for macular edema in Switzerland. In contrast to lasers, anti-VEGF drugs in macular edema not only preserve but also (sometimes significantly) improve visual acuity – and thus quality of life.

Two substances are currently approved in Switzerland: Ranibizumab (Lucentis®) and aflibercept (Eylea®). Bevacizumab (Avastin®) is also used in some cases, but off-label [4]. The treatment (intravitreal injection with 30 gauge needle, volume of about 0.05 ml) is relatively short and usually does not cause pain to the patient. After one month, the whole thing is re-evaluated. Thereafter, the therapy is repeated over a longer period of time (sometimes over half a year), usually on a monthly basis. In individuals who respond very well, in whom macular edema disappears and vision is good, the frequency of treatment can be greatly reduced, and in some cases stopped, after about three to four years. This is the case in more than 50% of patients [5]. Slightly less than half of patients continue to need treatments about two or three times a year. However, there is also a proportion that does not benefit from anti-VEGF therapy. This can have various reasons. For example, if no significant improvement is seen after six months, alternatives such as laser therapy or, in some cases, cortisone treatment should be discussed.

Studies have shown that therapy with drug VEGF inhibitors alone also leads to a decrease in peripheral neovascularization [6]. Of course, such therapy would be less cost-effective and significantly more costly than laser therapy. However, it shows that the effect of laser therapy on neovascularizations is probably due to VEGF reduction. However, drug therapy has not yet been approved for this indication. Furthermore, there is a lack of long-term experience over almost 40 years, as we have with laser, especially on the effect of long-term drug-induced VEGF suppression.

What place does vitrectomy have in the therapeutic concept?

Here, too, a distinction must be made between peripheral and central diseases. Patients with proliferations experienced vitreous hemorrhages more frequently in the past than today, i.e., bleeding from the newly formed blood vessels into the interior of the eye. If these bleeds do not clear up, vitrectomy is a treatment option. In other countries, many retinal detachments are observed due to diabetes, for which vitrectomy is the treatment of choice – fortunately, this problem has become rare in this country.

In macular disease, vitrectomy may be offered in selected cases. The data on efficacy show a large interindividual variance and do not allow a clear recommendation for surgical intervention. There are situations in which patients benefit, but at the same time severe deterioration after vitrectomy has been observed.

A recently published paper by Jackson et al. [7] concludes that vitrectomy has a considerable complication rate and patient selection should therefore be done very carefully. Nevertheless, vitrectomy has its place in the therapeutic concept and should not be completely forgotten. It plays a more important role in non-absorptive hemorrhage and especially in retinal detachment, where there are no other therapeutic options.

Are there therapeutic novelties or relevant developments in the field of diabetic eye damage?

No, there are no significant new approaches on the horizon that would revolutionize therapy in the next year or two. The last major breakthrough was anti-VEGF therapy. Currently, we are investigating to what extent we can influence the inflammatory component in the diabetic eye with immunomodulators, e.g., interleukin 6 antagonists. The concept has been known for some time, since about 2005, but there are no really good or reliable results yet. Another therapeutic approach is to influence the inflammatory cascade via intraocular cortisone preparations.

There are also various research approaches in the systemic field. Attempts are being made to address microangiopathy by supporting the repair function of the endothelium in the blood vessels, e.g., using stem cell therapy. The endothelium is permanently renewed or repaired by certain cells from the bone marrow; in diabetes, the repair function is severely limited. Researchers now want to increasingly stimulate these cells to leave the bone marrow in diabetics as well. Furthermore, their repair activity should be stimulated. For example, medications can help flush the cells out into the blood. Or you could take blood from the patient, enrich the cells and reinfuse them.

In your experience, how well does interdisciplinary collaboration work (general practitioner, diabetologist, ophthalmologist)?

In my experience, the cooperation works well. When diabetes is diagnosed, whether at our hospital or at the primary care physician’s office, the patient is routinely scheduled for an eye exam. It is important that patients are called up regularly for checks. The good cooperation is also reflected in the blindness and vitrectomy rates due to diabetes, which are very low in Switzerland compared to other countries. Health awareness and access to the health care system are good in this country.

Interview: Andreas Grossmann

Literature:

- Yau JW, et al: Global prevalence and major risk factors of diabetic retinopathy. Diabetes Care 2012 Mar; 35(3): 556-564.

- Fong DS, et al: Retinopathy in diabetes. Diabetes Care 2004 Jan; 27 (Suppl 1): S84-87.

- Early Treatment Diabetic Retinopathy Study Research Group: Early photocoagulation for diabetic retinopathy. ETDRS report number 9. ophthalmology 1991 May; 98(5 Suppl): 766-785.

- Diabetic Retinopathy Clinical Research Network: Aflibercept, bevacizumab, or ranibizumab for diabetic macular edema. N Engl J Med 2015 Mar 26; 372(13): 1193-1203.

- Elman MJ, et al: Intravitreal ranibizumab for diabetic macular edema with prompt versus deferred laser treatment: 5-year randomized trial results. Ophthalmology 2015 Feb; 122(2): 375-381.

- Diabetic Retinopathy Clinical Research Network: Panretinal Photocoagulation vs Intravitreous Ranibizumab for Proliferative Diabetic Retinopathy: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA 2015 Nov 24; 314(20): 2137-2146.

- Jackson TL, et al: The Royal College of Ophthalmologists’ National Ophthalmology Database Study of Vitreoretinal Surgery: Report 6, Diabetic Vitrectomy. JAMA Ophthalmol 2016 Jan 1; 134(1): 79-85.

CARDIOVASC 2016; 15(3): 26-30