As a primary care physician, how should I respond to people who are experiencing severe psychological distress? And how can I, as a doctor, help these people cope better with a serious diagnosis, an accident or an experience of violence? Jan Gysi, M.D., a specialist in psychiatry and psychotherapy in Bern and a specialist in psychotraumatology, answered these questions during a workshop at the Swiss Family Docs Congress and provided tips on how to deal with traumatized persons.

Some situations that may occur in any family practice:

- A woman calls: Her father collapsed unexpectedly a few hours ago and died after an attempt at resuscitation. Now her mother is beside herself. She was screaming and unresponsive.

- You have to tell a 50-year-old, otherwise perfectly healthy and unsuspecting man that he has already metastasized bronchial carcinoma.

- A young woman who comes to the practice because of a urinary tract infection tells us that she was raped by a chance acquaintance while out last weekend.

Repeated or one-time trauma?

Trauma is distinguished according to two criteria: Is it a one-time trauma (accident, death of a close caregiver, robbery, rape) or a repeated trauma (war, famine, torture, domestic violence, sexual abuse)? And is the trauma caused by people or by natural forces? These aspects play an important role in the processing of the trauma. Primary care providers are most often confronted in practice with unique traumas and their sequelae, i.e., acute stress reactions, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), anxiety and adjustment disorders, and affective disorders. The speaker drew attention to the fact that the current ICD-11 no longer lists “acute stress reaction” (F43.0) – today it is assumed that an acute reaction to severe stress is nothing pathological.

Fear, anger or shame

How a person is able to process trauma depends greatly on how they experienced it. To illustrate, Dr. Gysi told the fictional story of an avalanche accident in three versions:

- A man and his friend are skiing on a secured slope. Due to unfortunate circumstances, they are caught in an avalanche and experience mortal fear. Both barely survive.

- The man and his friend arrive at an open slope. They are caught by an avalanche and experience mortal fear, but survive unharmed. Later they learn that the slope should have been closed due to high avalanche danger. Only due to the negligence of ski slope workers, the avalanche accident occurred.

- The man and his friend arrive at a closed slope. The man persuades his friend to ignore the prohibition sign and drive down the closed slope. Both get caught in an avalanche and barely survive.

According to current diagnostic criteria, if PTSD develops after such an event, it is the same disorder regardless of the triggering situation: a stressful event with extraordinary threat and fear of death leads to specific post-traumatic symptoms. However, practice shows that different PTSD develops:

- Anxiety-focused PTSD: primarily hypervigilance, chronic anxiety, mistrust, intrusions, nightmares with feelings of fear and powerlessness.

- Anger-focused PTSD: primarily aggression, irritability, anger fantasies and impulses, intrusions, nightmares with feelings of anger and powerlessness.

- Shame-based PTSD: primarily self-hatred and self-loathing, fantasies and impulses to self-punish. Nightmares with fear/rage and belief of being a bad person and responsible for the trauma.

There are many treatment options for anxiety-related disorders and the chances of success are high. The situation is different for shame-based disorders. These are often the consequences of sexual violence, humiliation, neglect or even after situations in which the affected person had to use violence himself. The symptomatology is much more complicated than in anxiety disorders (self-injury, distrust, suicidal tendencies, etc.), partly because the affected people cannot talk about what they have experienced and the accompanying feelings. There are fewer treatment options, success rates are low, and mental illness and suicide as a result of trauma are more common than for anxiety- or anger-related disorders.

Reactions of the environment are decisive

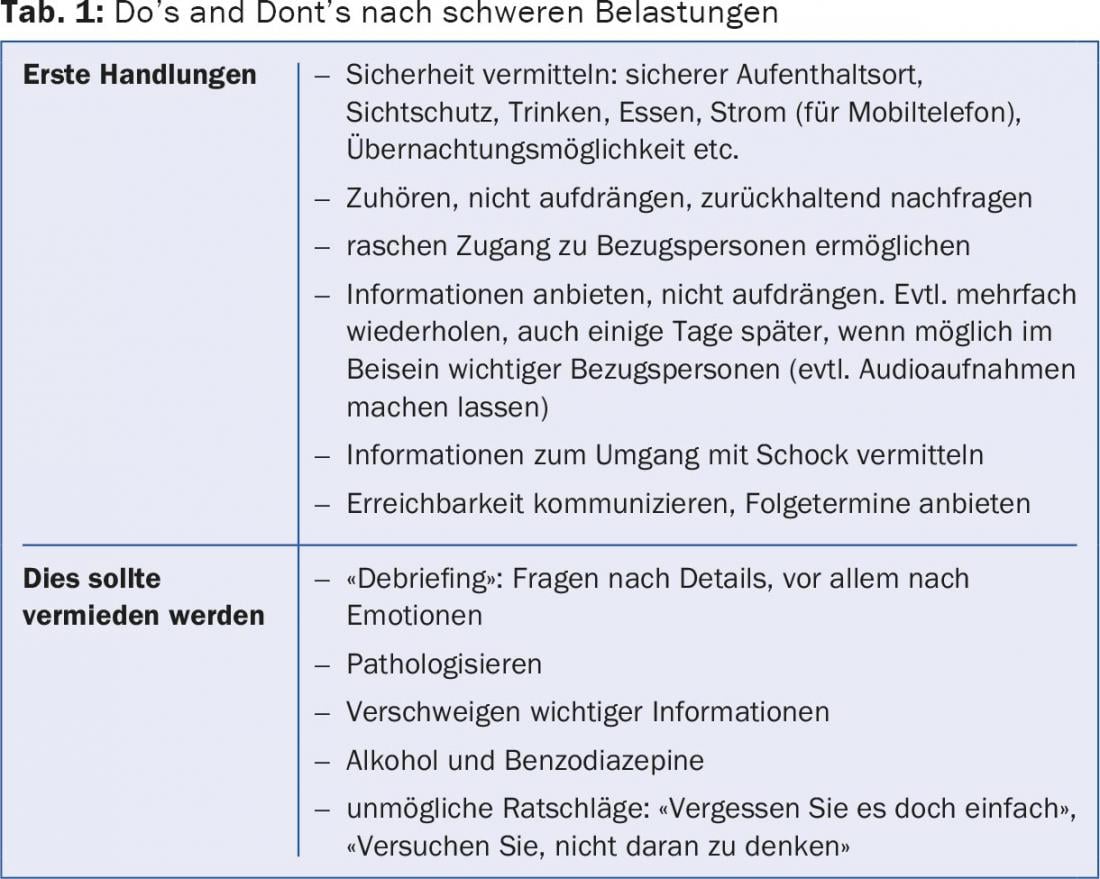

PTSD develops in four phases. In the beginning, there is the “stressful event of extraordinary magnitude that would cause deep despair in almost anyone” (ICD-10). This is followed by the reaction of the next of kin and, in phase three, the reactions of the extended personal environment (acquaintances, neighbors, work colleagues, doctors, etc.). Phase four focuses on the responses of professionals such as the police, counseling centers, judiciary, etc. The reactions of those around you are critical to whether PTSD develops at all. Therefore, it is also important as a physician to respond properly (psychological first aid) to people who have experienced trauma ( Table 1).

The speaker recommended becoming familiar with appropriate resources such as the local care team or emergency chaplaincy (www.notfallseelsorge.ch) in the event of an emergency. The flyer “Recommendations for dealing with stressful events”, which is available in various languages (www.smsv.ch/fileadmin/filesharing/Download/11_Ausbildungsunter lagen/Flyer_Umgang_mit_Betroffenen.pdf), is also helpful.

“If possible, try not to prescribe benzodiazepines or sleeping pills in the acute situation,” Dr. Gysi said. “Rather, one should convey to those affected that it is perfectly normal for them to sleep poorly in the first period after the event.” Other normal reactions to stress are bewilderment, denial (“That can’t be!”), guilt, anger, resentment and fear. While some remain silent and withdraw, others want to talk about the event again and again. The best therapy is a social support network (family, friends, neighbors, etc.). Therefore, it makes sense to also inform the family about appropriate support measures: keeping in touch with the affected person, communicating openly (also about anger, shame or guilt), avoiding alcohol, exercise (walks), eating and drinking regularly, not making any fundamental life decisions, networking with contact points (victim support, cancer league, etc.).

If symptoms persist, trauma therapy

90% of all people can process and integrate individual traumas within 4-6 months. If this is not the case, trauma therapy may be appropriate. Signs of ongoing problems are:

- Distressing symptoms after more than three months

- Intrusions in everyday life (traumatic memories over which the affected person has no control)

- Sleep disorders, regular nightmares

- Emotional detachment or flooding states

- Anxiety and panic states, anger, feelings of guilt

- Performance kink.

Source: Swiss Family Docs Conference, August 27-28, 2015, Bern

GP PRACTICE 2015; 10(10): 30-32