What happens when two or more medications are taken at the same time? The answer is: there may be an increase or decrease in drug effects. In some cases this is tolerable or even desirable, but in the worst cases it leads to toxicities and treatment failure. At the 96th annual meeting of the SGDV in Basel, the topic was discussed in more detail.

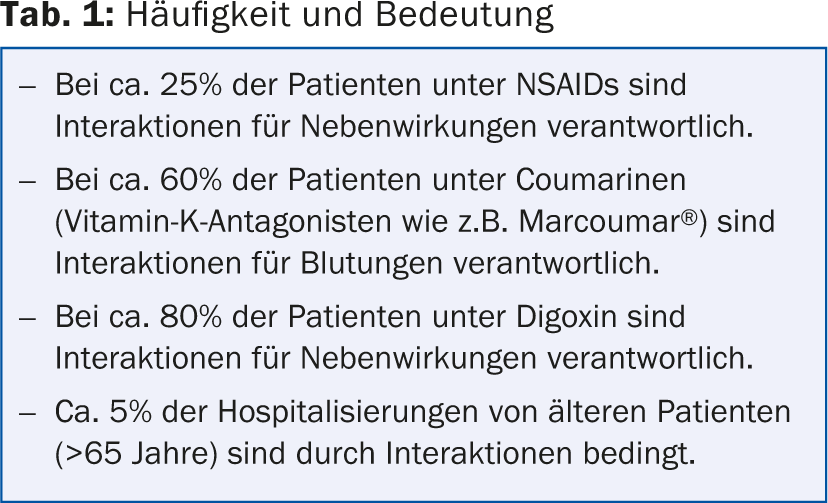

According to PD Dr. med. Manuel Haschke, University Hospital Basel, the frequency of interactions depends on the individual patient and, of course, the therapy. In the outpatient setting, it is about 2-6% of patients; in hospitals, it is about 40-50%. “Interactions are responsible for 5-30% of all adverse drug events (Table 1),” the speaker said. “Most of these could be prevented because the causes are known. A risk factor for interactions is logically polypharmacy, but also the high number of prescribing physicians, new drugs and ‘over-the-counter’ drugs, i.e. self-medication. Changes – whether by starting a new drug, in the combination, or else discontinuing it – always pose a risk situation.”

Problematic drugs

For drugs with a narrow therapeutic range (e.g., antiepileptics, anticoagulants, immunosuppressants), interactions may increase the risk for the occurrence of adverse effects. Furthermore, problematic interactions may occur if critical enzymes such as CYP3A, CYP2C9, xanthine oxidase, or MAO are significantly involved in drug metabolism. Drugs that are excreted renally or biliterally in unchanged form are also often affected – the same applies to those with high protein binding especially coumarin derivatives and sulfonylureas.

Interacting drugs are usually inhibitors or inducers of key enzymes in drug metabolism or of drug transporters. The high protein binding (especially of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs) may also promote interactions.

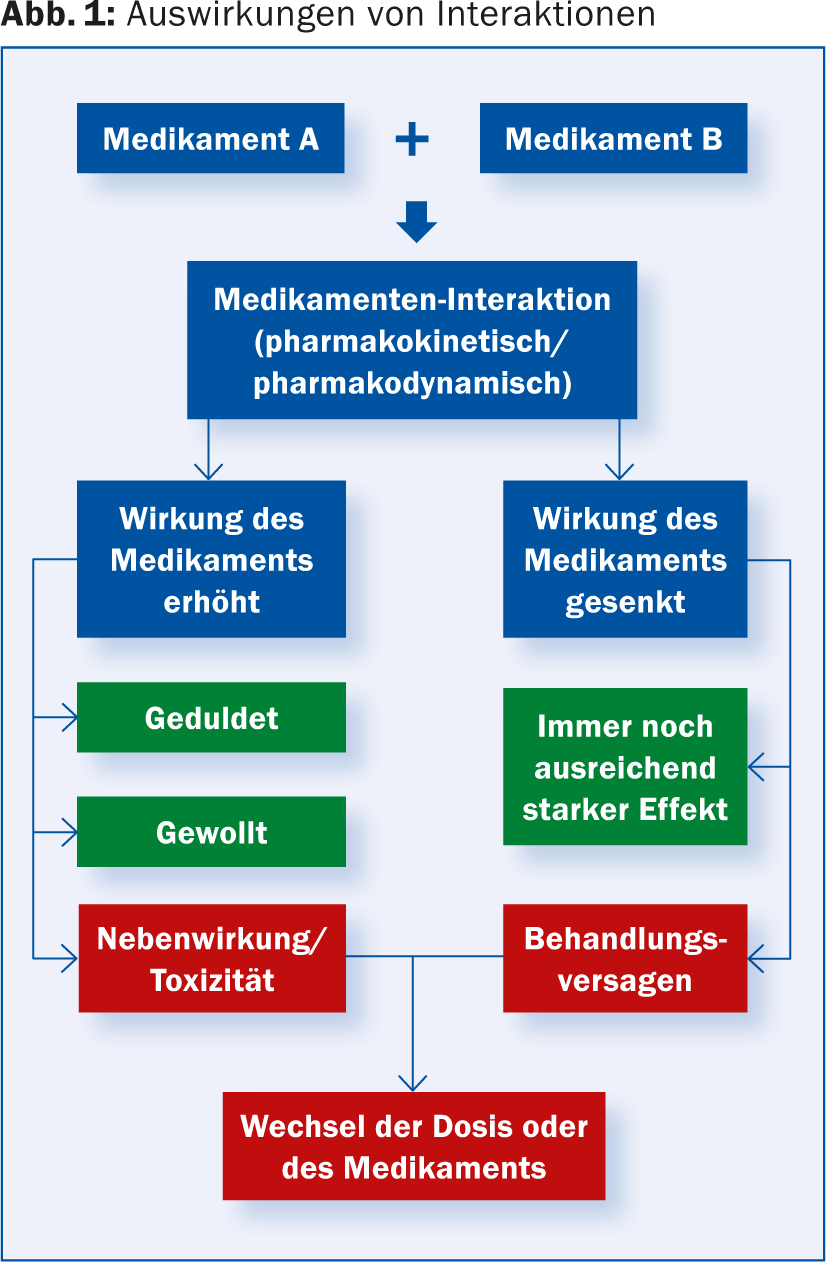

Figure 1 summarizes possible effects of interactions in an overview.

Division

Drug interactions can be described in three different ways. On the one hand, there are the interactions outside the body: the pharmaceutical interactions (incompatibility, e.g. precipitation in the infusion solution). Pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic interactions occur within the body. The former involve a change in serum concentration of one or both interactants, while the latter involve a mutual enhancement or attenuation of effect without a change in serum concentration. Interactions may involve all four pharmacokinetic processes (ADME):

A: Absorption

D: Distribution

M: Metabolism

E: Elimination.

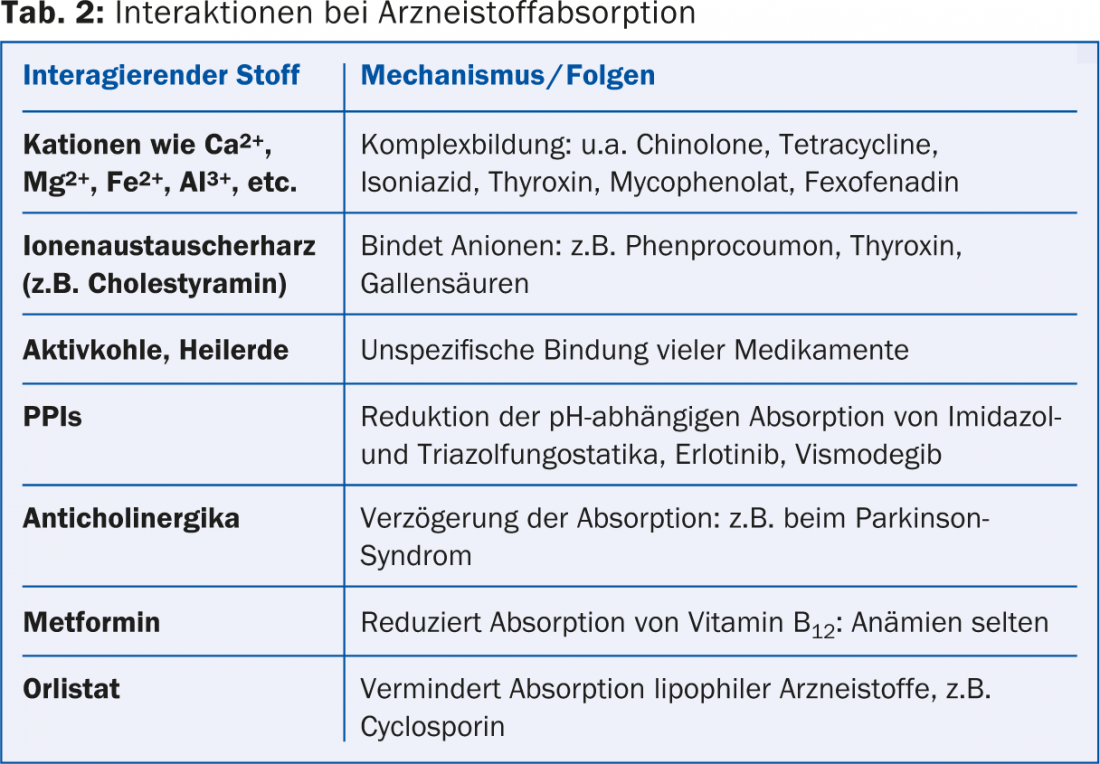

Examples of drug absorption interactions are summarized in Table 2.

“Regarding metabolism, important CYP3A4 inhibitors are azole antifungals such as ketoconazole or itraconazole, antibiotics such as clarithromycin, protease inhibitors such as ritonavir or saquinavir, and, as is well known, grapefruit juice. CYP3A4 inducers include classic antiepileptic drugs such as carbamazepine, antibiotics such as rifampicin, NNRTIs such as nevirapine, and St. John’s wort extracts. In combination with a drug like midazolam, which is metabolized by CYP3A4, relevant interactions may now occur,” the speaker explained. “CYP3A4 inhibitors and inducers have the potential to greatly alter plasma concentrations of midazolam and thus also decrease or increase its effects. Dose adjustments become necessary.” With inhibitors, the effect begins minutes to hours after the inhibitor is started, and the end depends on its half-life (reversible inhibitor) or on new formation of the inhibited enzyme (irreversible inhibitor). For inducers, the effect starts three to five days after the start of therapy. Maximum induction is reached after about two weeks. After discontinuation of the inducer, it again takes about two weeks until the induction is no longer detectable.

Pharmacodynamic interactions – Biologics

There are no systematic studies on potential interactions with biologics. However, since they are usually administered parenterally and have different degradation pathways than so-called “low-molecular weight drugs”, pharmacokinetic interactions are unlikely. However, pharmacodynamic effects are possible (e.g., increased immunosuppression increased infections).

Conclusion

“Drug-drug interactions are qualitatively and quantitatively significant, but mostly known and therefore avoidable. Common and important mechanisms are inhibition/induction of enzymes and/or transport proteins in drugs with a narrow therapeutic range and pharmacodynamic interactions (also in biologics). Particular caution is required when drug combinations are changed,” concluded Dr. Haschke.

Source: “Drug Interactions,” paper presented at the 96th Annual Meeting of the SGDV, September 4-6, Basel.

DERMATOLOGIE PRAXIS 2014; 24(5): 42-43