UV radiation is involved in many skin diseases. The spectrum ranges from acute damage in the sense of dermatitis solaris to chronic late effects such as premature skin aging or the development of skin cancer. Common to these UV-induced changes is excessive acute or chronic UV exposure. The main triggers are the medium wavelengths in the UV-B range between 290 and 320 nm. If skin reactions occur as a result of UV exposure in an everyday, i.e. moderate, context, we speak of photodermatoses in the true sense.

The trigger of photodermatosis is often UV-A in the wavelength range of 320-400 nm. Unlike excessive UV exposure, which causes changes in everyone depending on skin type, photodermatoses affect only appropriately predisposed individuals. A distinction is made between primary photodermatoses due to an (exogenous) photosensitizer and secondary photodermatoses in the context of an endogenous cause.

Idiopathic primary photodermatoses

By definition, idiopathic primary photodermatoses are said to occur when the etiology is unknown.

Urticaria solaris is a rare disease. This form of urticaria can be triggered by the entire UV spectrum up to visible light. After appropriate exposure, wheals form(Fig. 1), and in unfavorable cases, whole-body exposure can lead to anaphylactic shock. Due to the usually insufficient effect of systemic antihistamines, UV therapy or photochemotherapy (PUVA) is performed.

Fig. 1: Urticaria solaris: Urticae after determination of the UV threshold.

Polymorphic light dermatosis (syn. “sun allergy”, Mallorca acne, polymorphic light eruption) is the most common photodermatosis in Central Europe. The etiology is unknown. Sun exposure is followed by pruriginous skin lesions that may vary in terms of primary florescence from macules to papulovesicles(Fig. 2) to urticae and plaques or multiforme reactions. The disease owes its name to this circumstance.

Fig. 2: Polymorphous light dermatosis

However, the individual patient usually shows a monomorphic picture with the formation of the same efflorescences again and again with renewed sun exposure. Otherwise light-protected areas are affected, whereas the face, for example, is often left out. A few hours after UV exposure, itchy changes occur on the chest, upper arms, back of the hands, thighs and possibly cheeks. With UV abstinence, these disappear within days without leaving residual skin changes.

In addition to UV protection with suitable clothing – sunscreens are usually not sufficient – and gradual habituation to the sun, UV therapy in the sense of “hardening” in the spring or before vacation trips can be useful for strongly symptomatic patients. This should be done with medical irradiation units under the control of the specialist and not in the solarium. In cases of pre-existing polymorphous light dermatosis, the use of systemic antihistamines and topical steroids may relieve symptoms and accelerate spontaneous remission.

Hydroa vacciniformia is also very rare and is characterized by the acute appearance of hemorrhagic vesicles on the face (Fig. 3) and hands, which heal with scarring. In the unclear etiology, Epstein-Barr virus is discussed as a possible trigger.

Fig. 3: Hydroa vacciniformia: healing erosions as a residual condition after hammermorrhagic vesicles.

Actinic prurigo is more commonly observed as a familial variant in patients of indigenous origin in the Americas and is a rarity in Europe. In chronically sun-exposed areas, pruritic skin lesions occur that hardly respond to topical or systemic therapies except for thalidomide.

The term chronic actinic dermatitis includes older terms such as persistent light reaction, actinic reticuloid, and photosensitive eczema. The clinic corresponds to chronic lichenified eczema in the light-exposed areas. Mostly the face and the back of the hands are affected. In addition to strict exposure prophylaxis, PUVA therapy or immunosuppressants (systemic glucocorticoids, azathioprine, cyclosporine-A) are used depending on the severity.

Photosensitivity when an exogenous trigger is involved.

Acute urticarial erythema with blisters and subsequent hyperpigmentation in a bizarre, often streaky distribution corresponding to contact with plant parts should suggest the diagnosis of phytophotodermatitis (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4: Phytophotodermatitis

The plant as a trigger is not primarily apparent to the patients in this case, as there is delayed formation of the skin changes with a maximum after 72 hours. The UV doses (mostly UV-A) necessary to trigger a photoxic reaction are reached even under dense cloud cover. Triggers are plants containing furanocoumarins, and the furanocoumarins act as photosensitizers. In addition to ornamental plants, plant parts of foods such as celery, parsnip or citrus fruits are among the possible triggers.

A similar clinical picture may also be present in the so-called Berloque dermatitis, which, however, is not caused by plants but by perfume or perfumed cosmetics. The triggers are again of plant origin, as they are essential oils, often bergamot oils, which contain furanocoumarins. Treatment of phototoxic reactions in the acute stage is with topical glucocorticoids of drug class 3 or 4 in a low occluding base such as a cream or lotion.

Large blisters require treatment as for 2nd degree burns. Local corticosteroid application, possibly in conjunction with antiseptics, beyond the acute healing phase is important to prevent subsequent pigmentary shift. Consistent sun protection with unscented sunscreens is indicated for existing hyperpigmentation. Lightening can be assisted with azelaic acid, topical vitamin A acid, or 5% hydroquinone with 1% hydrocortisone, taking into account the risk of renewed inflammatory irritation with further pigmentary shift.

Phototoxic drug reactions also belong to the phototoxic reactions, although here the clinical picture is characterized not by blisters and signs of abrasion but by exanthema in light-exposed distribution (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5: Phototoxic reaction to torasemide.

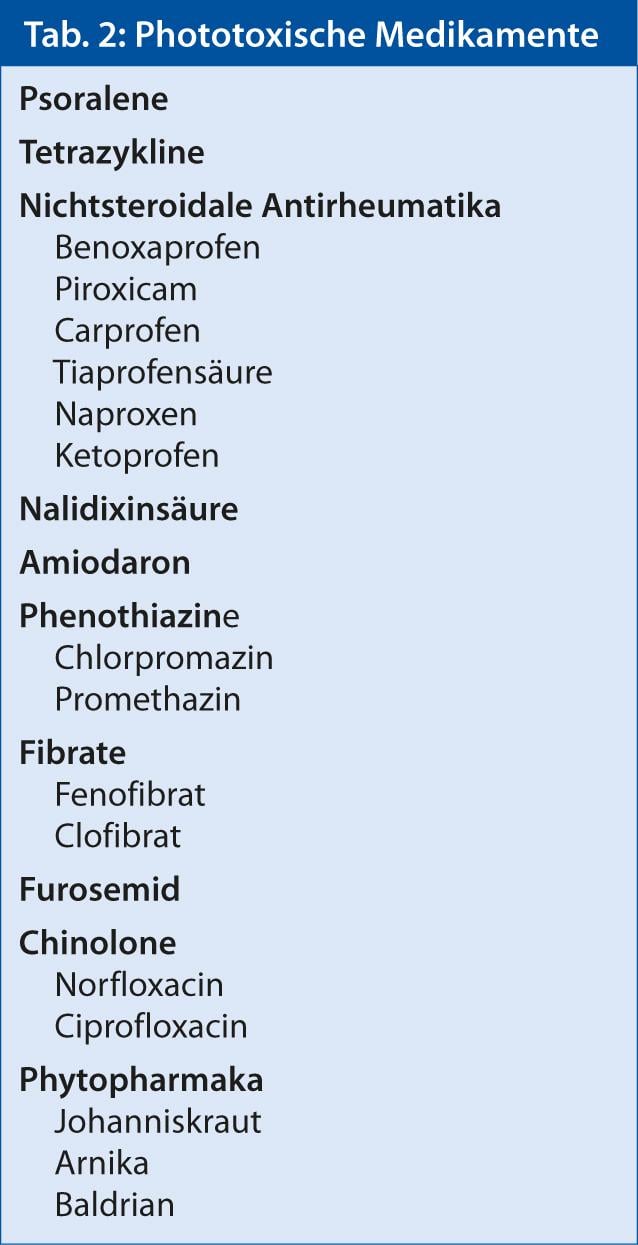

The skin changes range from urticarial pictures to sunburn-like reactions to vesicular exanthema. The most common triggers are summarized in Table 2.

If it is not an obligate photosensitizer but an individual sensitization, it is referred to as photoallergic contact dermatitis or systemic photoallergic dermatitis.

Secondary photodermatoses with endogenous cause.

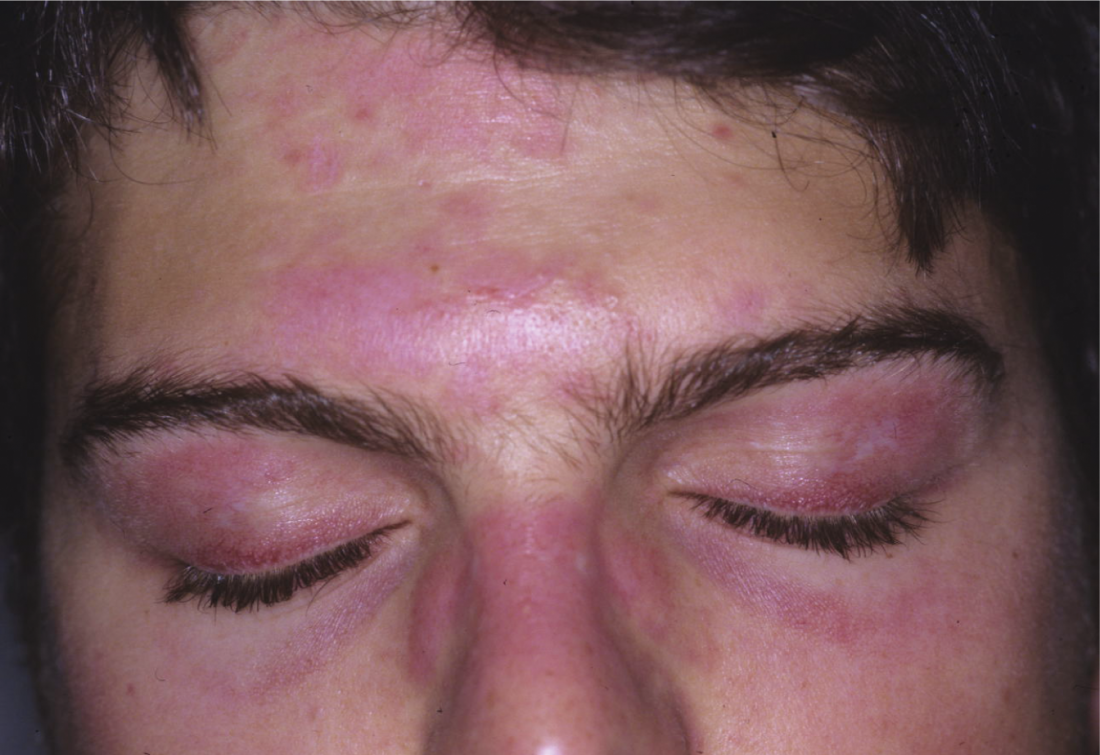

Secondary photodermatoses range from genetically determined DNA repair defects (xeroderma pigmentosum) to metabolic diseases such as the porphyrias to photosensitivity in collagenoses such as lupus erythematosus or dermatomyositis (Fig. 6).

Fig. 6: Heliotropic erythema in dermatomyositis

Diagnostics

In the diagnosis of photodermatoses, the anamnesis and, in the case of phytophotodermatitis for example, the typical clinic are decisive. Further testing with determination of the UV threshold, photo patch testing and possibly photoprovocation where indicated can be performed in specialized centers (usually dermatological institutions).

Further reading:

- Lehmann P: Diagnostics of photodermatoses. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges 2006; 4: 965-975.

- Bylaite M, Grigaitiene J, Lapinskaite GS: Photodermatoses: classification, evaluation and management. Br J Dermatol 2009; 161 Suppl 3: 61-68.

- Lehmann P, Schwarz T: Photodermatoses: Diagnosis and Treatment. Dtsch Arztebl Int 2011; 108: 135-141.

- Chantorn R, Lim HW, Shwayder TA: Photosensitivity disorders in children: part I. J Am Acad Dermatol 2012; 67: 1093.e1-18.

- Chantorn R, Lim HW, Shwayder TA: Photosensitivity disorders in children: part II. J Am Acad Dermatol 2012; 67: 1113.e1-15.