Anemias are a common problem in family practice. On the basis of the medical history and a few laboratory parameters, about 90% of anemias can be clarified and causally explained in the general practitioner’s office [1]. Dr. med. Christoph Merlo, Lucerne, presented a correspondingly simple clarification algorithm in a workshop

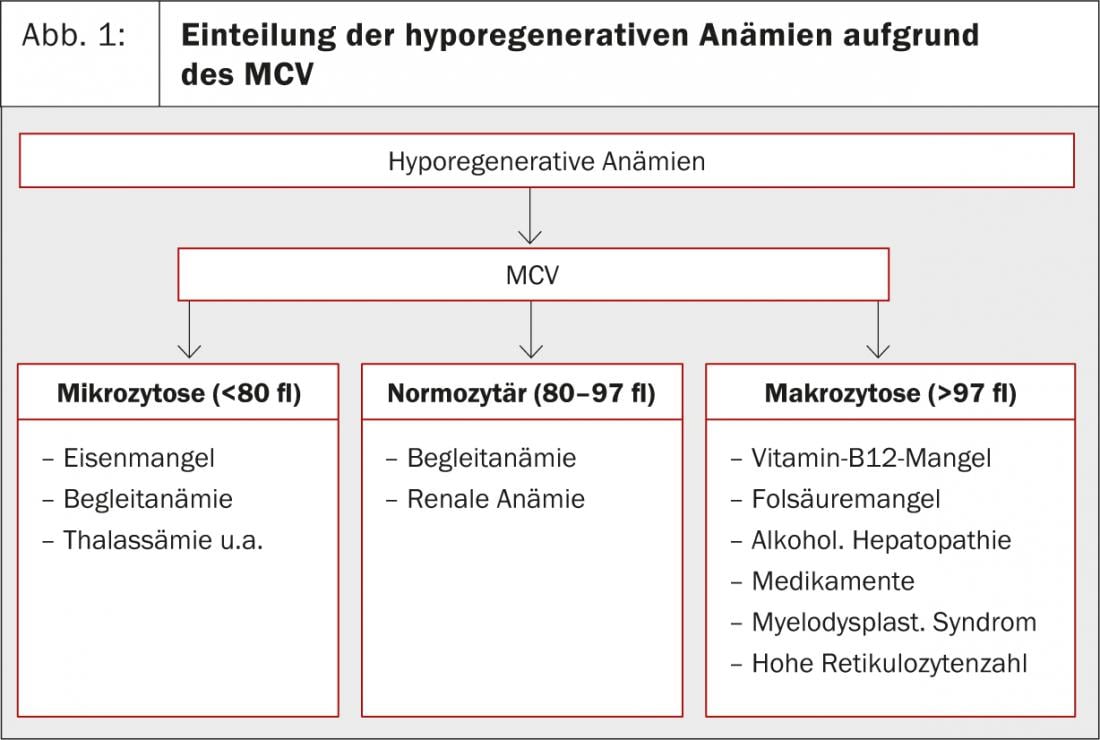

Defined by decreased hemoglobin concentration, the anemia-defining hemoglobin lower limit depends on the reference population and sometimes on the analyzer. The standard hemoglobin values used by various laboratories may therefore deviate from the standard values defined by the WHO(Table 1). The WHO definition also does not take into account that hemoglobin averages physiologically decrease in men from about 65 years of age, but not in women. “However, the decision as to whether or not you want to perform an anemia workup is made individually in the practice anyway. Much more important than the absolute hemoglobin value is the patient’s history, symptoms and comorbidities,” explained Christoph Merlo, MD, Lucerne. In addition to the classic symptoms of fatigue, dyspnea on exertion, intolerance of performance, palpitations/tachycardia, anemia can also cause headaches.

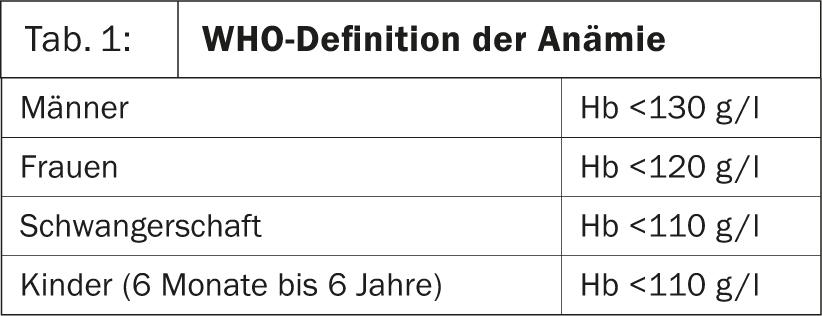

Anemias are classified based on reticulocyte count and MCV (mean corpuscular volume). If the reticulocyte count is below 100 G/l, it is a hyporegenerative anemia. If it is above 100 G/l, it is a hyperregenerative anemia. For the latter, there are only two possible causes: subacute hemorrhage and hemolysis. “A passive increase in reticulocytes can also be observed when a patient with iron deficiency or vitamin B12 deficiency is freshly substituted,” Dr. Merlo added. Hyporegenerative anemias are further subdivided into microcytic, normocytic, and macrocytic anemias based on MCV(Fig. 1).

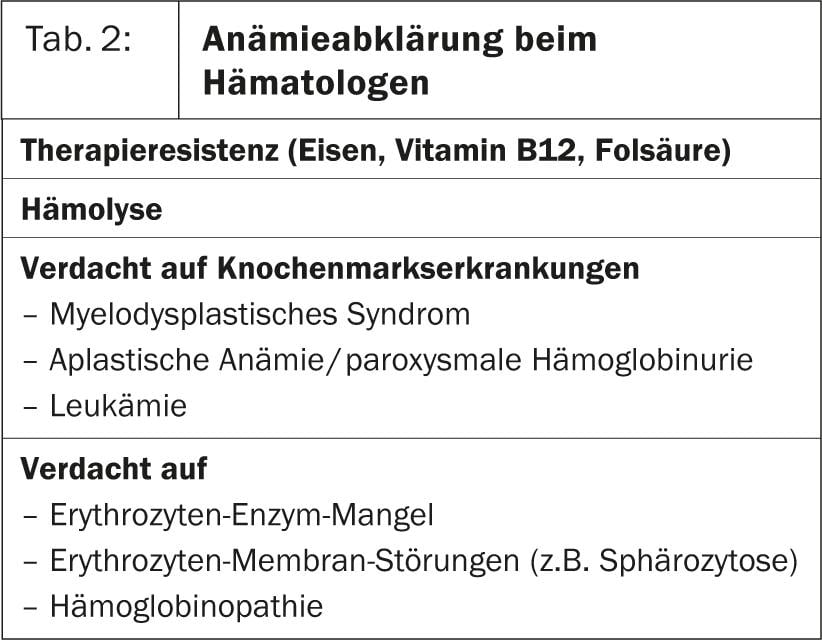

In some cases, the cause of the anemia, which is primarily assessed with a hematogram consisting of hemoglobin, hematocrit, erythrocyte count, indices, and leukocyte count, can already be clarified on the basis of the medical history (for example, anemia under chemotherapy). If the MCV then also matches, further clarification can be dispensed with in these cases. However, a simple basic laboratory consisting of reticulocyte count, ferritin including CRP and ALAT (GPT), vitamin B12, erythrocyte folic acid, and creatinine (to determine creatinine clearance) is usually required to clarify the cause of anemia. This simple algorithm, which can be used to conclusively clarify about 90% of anemias in family practice [1], is shown in Figure 2. If bone marrow disease is suspected or if specific hemolytic anemias need to be evaluated, the patient should be referred to a hematologist for further evaluation (Table 2).

Iron deficiency, chronic renal failure, and other chronic diseases (tumors, inflammation) are among the most common causes of anemia in a primary care internal medicine practice [1]. “In our own survey, about one-third of patients had more than one cause of anemia,” Dr. Merlo adds.

Ferritin value shows iron deficiency

The best parameter for detecting iron deficiency is ferritin. Serum iron is not suitable for this purpose, as it is subject to strong diurnal fluctuations. The only cause of decreased ferritin is iron deficiency. “For practical purposes, the following rule of thumb proves its worth: if the serum ferritin level is below 50 μg/l, iron deficiency is possible, below 30 μg/l very likely, and below 15 μg/l proven,” explains Dr. Merlo. Since ferritin reacts like an acute phase protein, i.e. is elevated in inflammation, and can also be elevated in chronic liver disease, CRP and alanine aminotransferase (ALAT) should always be determined at the same time as ferritin. In chronic inflammatory conditions with elevated CRP, iron deficiency can be detected using the elevated soluble transferrin receptor along with other special tests.

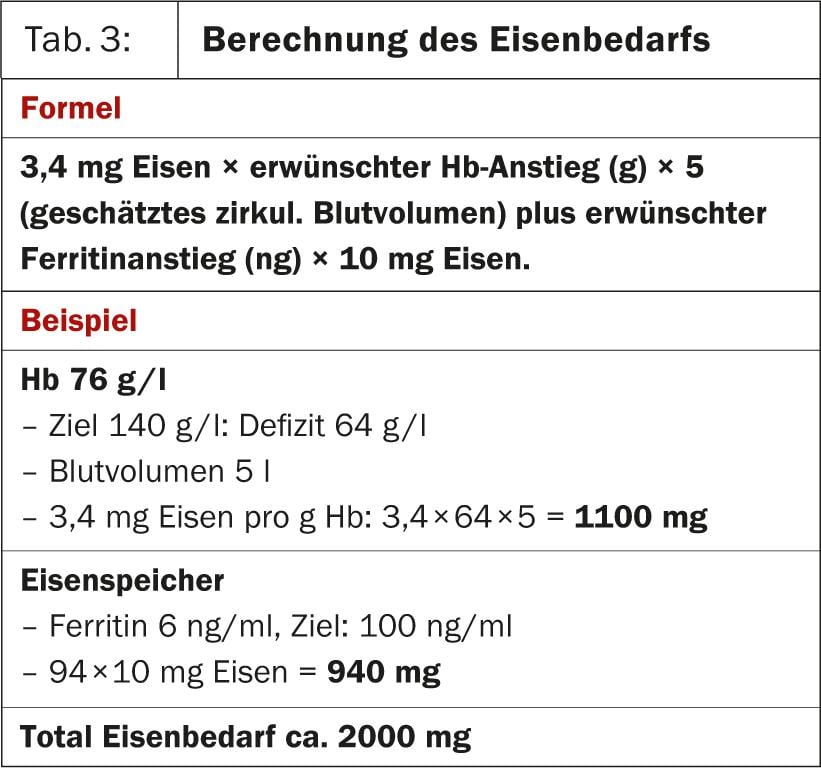

Of course, iron supplementation should be done only in cases of proven deficiency. Iron requirements can be calculated from the hemoglobin and ferritin deficits using a simple formula (Table 3).

It should also be noted that with oral substitution, only 10% of the iron supplied is absorbed. Thus, for an iron requirement of 2000 mg, a total of 20 000 mg must be given. Divalent iron preparations must be administered fasting, otherwise absorption is even worse. Trivalent iron (Maltofer®) is first converted to divalent iron in the intestine and can be taken with meals, which may improve tolerability. In cases of poor compliance, e.g., multimorbid patients with polypharmacy, renal anemia, or poor tolerance, i.v. iron substitution offers an alternative. To monitor the success of therapy, an increase in reticulocytes can be observed after 5-10 days and an increase in hemoglobin after two weeks. Intravenous iron stimulates ferritin, so in this case it is necessary to wait at least four weeks until this value is checked.

Source: “Anemia assessment in practice,” workshop at the 81st Annual Meeting of the SGIM, May 29-31, 2013, Basel.

Literature:

- Merlo CM, Wuillemin WA: Prevalence and causes of anemia in an urban family practice. Praxis 2008; 97: 713-718.

- Merlo CM, Wuillemin WA: Diagnosis and therapy of anemia in practice. Praxis 2009; 98: 191-199.