The cause of IBS should be identified by taking a medical history and performing a symptom-specific workup. Which combination therapy can be used to treat irritable bowel syndrome is clarified in the following article.

Irritable bowel syndrome or “irritable bowel syndrome” (IBS), according to the term in international use, is one of the most common gastrointestinal disorders [1]. Symptoms of irritable bowel syndrome affect 10-20% of adults. Depending on the predominance of a patient’s bowel habits, IBS can be divided into four subtypes [2]: with predominantly constipation, with predominantly diarrhea, a mixed type with alternating constipation and diarrhea, and a nonspecific type.

Often, patients with IBS suffer from other functional gastrointestinal complaints such as dyspepsia, as well as extraintestinal disorders such as insomnia, back pain, headaches, and depression. These IBS-associated complaints contribute, in part, to the significant morbidity and socioeconomic costs of this condition.

Pathophysiology

Irritable bowel syndrome is pathogenetically explained by a combination or complex interaction of various factors [1]. The most important factors are motility disorders, gastrointestinal sensory dysfunction (visceral hypersensitivity), and psychosocial influences. Various motility problems, such as an accelerated or delayed intestinal transit time, an increased gastrocolic reflex with diarrhea after meals, or a functional defecation disorder with consecutive constipation, can be demonstrated in irritable bowel syndrome.

The increased perception of visceral stimuli may be due to a lowering of the stimulus threshold within the sensory innervation of the gastrointestinal tract as well as in the processing and perception of sensitive visceral stimuli in the central nervous system (posterior horn of the spinal cord, CNS). The perception threshold for visceral stimuli is affected by both physical and psychological stress. Visceral sensory nerves are activated by a variety of osmotic, chemical, and mechanical endoluminal stimuli. Experimental and clinical studies have identified several mechanisms or stimuli underlying this visceral hypersensitivity. These include an abnormal mucosal immune response triggered by gastroenteritis (postinfectious irritable bowel syndrome), various dietary components (malabsorbed sugars such as lactose and fructose), altered intestinal bacterial flora (dysbiosis), and endoluminal substances such as short-chain fatty acids and bile salts.

In postinfectious irritable bowel syndrome, the abnormal but only microscopic mucosal inflammatory response (increased number of mast cells and T lymphocytes) leads, among other things, to activation of enterochromaffin cells and thus increased serotonin activity and cytokine production, which in turn stimulate motor and sensory receptors.

Diagnosis and differential diagnosis

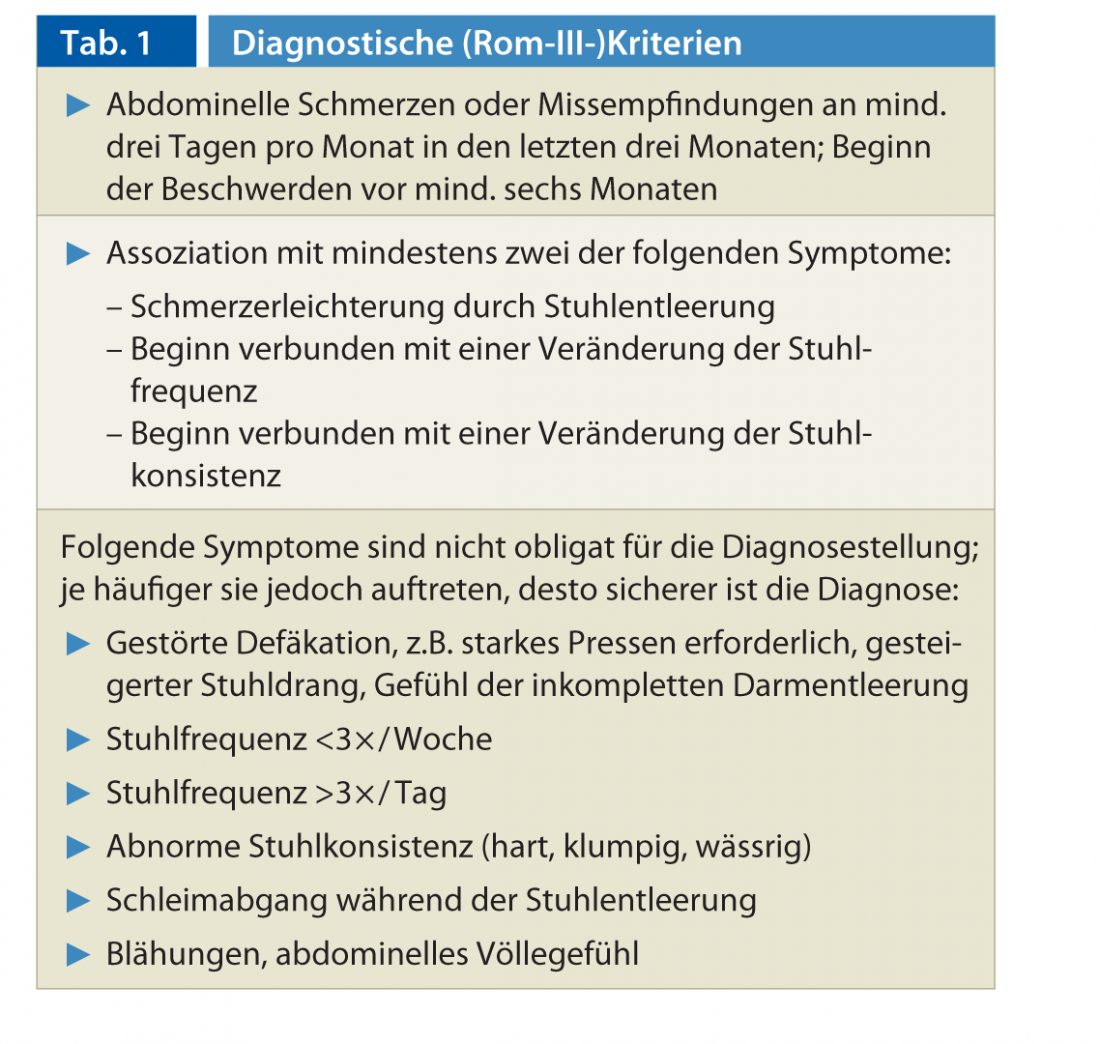

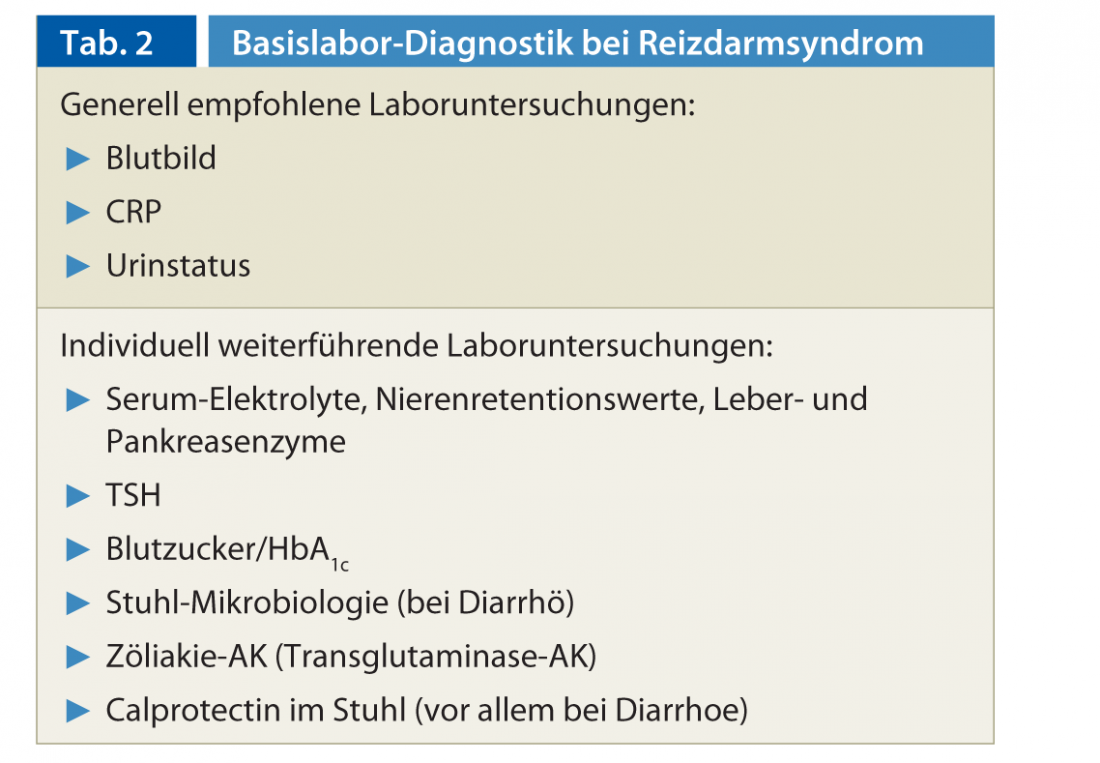

The diagnosis of IBS can be made clinically with a high degree of certainty using the Rome III criteria (Table 1) [3]. The diagnosis of IBS should not be a diagnosis of exclusion, but should be based on the typical constellation of symptoms after a basic diagnosis (Tab. 2) and an individual, problem-oriented further diagnosis [2]. This is based on factors such as patient age, severity of symptoms, presence of atypical symptoms (weight loss, anemia, signs of inflammation), risk factors (family history of gastrointestinal tumors, prior abdominal surgery?), concomitant diseases, and also patient expectations. Based on these parameters, it must be decided whether colonoscopy, image diagnostics or special laboratory tests are required.

For the clarification of diarrhea or flatulence, celiac screening by means of determination of transglutaminase IgA antibodies is recommended. Lactose or fructose intolerance can exacerbate irritable bowel symptoms and, if suspected, can be detected by an H2 breath test. Fecal calprotectin as a marker of inflammation in the gastrointestinal tract is useful for differentiation from an organic cause of abdominal symptoms. However, an elevated value is non-specific and requires further investigation.

Therapy

Depending on the severity of the disease and the predominant symptoms, an individual therapy plan should be created. The basis of the treatment of a patient with IBS is conversation. It is important to put the patient in a position to better tolerate his complaints (“coping”) and to relieve his fears of a serious illness (especially cancer fear) and to alleviate acute increases in complaints with medication.

Depending on the intensity of the complaints, the following graduated scheme is recommended in the treatment:

- Enlightening conversation

- Modification of the diet

- Symptom-oriented drug therapy

- Psychosomatic treatment, behavioral therapy.

Diet: Many patients describe an increase in their symptoms after consuming certain foods such as fat, raw vegetables, spices, alcohol, coffee and dairy products. However, true food allergies in IBS are very rare. The prescription of a specific diet is usually not necessary, but nutritional counseling, which takes into account the individual tolerance of certain foods, is helpful. The FODMAP diet can improve flatulence and diarrhea in particular. In this diet, foods containing fermentable oligo-, di-, monosaccharides and polyanes are reduced.

Stool-regulating medications: In IBS with predominantly constipation, dietary fiber can accelerate stool transit time and improve stool consistency by increasing stool volume and stimulating intestinal peristalsis. However, the use of natural (bran or flaxseed) or artificial fiber or swelling agents (psyllium, isphagula, mucilaginosa, pectins) may increase symptoms, especially in IBS with predominantly pain or bloating. Compared to fibers such as bran, artificial fibers undergo less fermentative decomposition and are often better accepted by patients due to less gas formation.

In the constipation type, a combination with osmotic (lactulose, polyethylene glycol) laxatives may be required in persistent cases. New agents for the treatment of constipation include the highly selective 5-HT4 agonist prucalopride (Resolor®) and the chloride channel activator lubiprostrone (Amitiza®). In patients with constipation-dominant irritable bowel syndrome, studies with the guanylate cyclase C receptor agonist linaclotide showed significant improvement in abdominal pain and constipation. The substance is not yet approved in Switzerland for the treatment of moderate to severe irritable bowel syndrome with constipation.

In IBS with predominantly diarrhea, loperamide shows a slowing of stool transit time, improvement in stool consistency, and a decrease in urge to defecate. However, loperamide may increase abdominal pain. The dose and duration of loperamide should be adjusted individually according to the severity and course of symptoms. The combination of stool softeners as basic therapy and loperamide as an as-needed medication has a beneficial effect in diarrhea-dominant IBS.

Spasmolytics: The efficacy of these drugs, which are used for cramp-like pain or flatulence, is weak according to current studies. Representatives are anticholinergic substances (Buscopan®), calcium antagonists (Dicetel®), substances acting directly on the smooth muscles of the gastrointestinal tract such as relaxants (Duspatalin®) and peppermint oil (Colpermin®).

Antibiotics: The antibiotic rifaximin (not approved in Switzerland) has been shown to have a moderate, short-lasting effect in the treatment of IBS with flatulence and diarrhea [2]. However, due to the lack of long-term studies and the risk of resistance development, this substance is not a therapeutic option.

Antidepressants: tricyclic antidepressants are used preferentially in patients with diarrhea-dominant IBS to treat chronic refractory pain [1]. Often these patients have comorbidity with depression or anxiety. An analgesic and neuromodulatory effect is seen with tricyclic antidepressants at very low doses (e.g., 10-25 mg amitryptilline). Because of the anticholinergic effect, tricyclic antidepressants may have a negative impact on stool frequency and consistency in constipation-dominant IBS.

Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors have been shown to have a positive effect on quality of life in IBS patients.

Phythotherapeutics and probiotics: There are positive study results for the therapy of flatulence, abdominal distension, meteorism and/or flatulence with phythotherapeutics and probiotics, but the study quality is mostly low. The phythotherapeutic Iberogast® (nine plant extracts) is particularly suitable for the therapy of IBS with constipation and for flatulence.

CONCLUSION FOR PRACTICE

- The most important pathogenetic factors for IBS, in addition to disturbances in motility, are visceral hypersensitivity, impaired interaction between enteral and central nervous systems, and immunologic dysfunction.

- The diagnosis of irritable bowel syndrome is made clinically according to the Rome III criteria and on the basis of the typical medical history and a symptom-oriented workup.

- If symptoms such as flatulence or diarrhea are present, celiac screening should be performed.

- Determination of calprotectin in stool facilitates differentiation from organic gastrointestinal

- Diseases.

- Treatment includes patient education, lifestyle and dietary changes, concomitant drug therapy, and various forms of behavioral therapy.PD Miriam Thumshirn, MD.

Literature list at the publisher

PD Dr. med. Miriam Thumshirn

HAUSARZT PRAXIS 2013, No. 5; 6-8