Still, only one in two patients responds adequately to initial antidepressant therapy. This is despite an extensive range of therapies. Guideline-based treatment of unipolar depression can lead to significant increases in response and remission rates. The recommendations presented in the article are based on the treatment recommendations of the Swiss Society of Psychiatry and Psychotherapy (SGPP), the Swiss Society for Anxiety and Depression (SGAD), and the Swiss Society for Biological Psychiatry (SGBP).

Affective disorders are among the most common mental illnesses and cause a considerable amount of individual suffering as well as health economic costs. Their biopsychosocial etiology as well as their different courses place high demands on physicians practicing psychiatry. For unipolar depression alone, the lifetime prevalence is approximately 20% [1]. Despite an extensive range of psychotherapeutic and psychopharmacological intervention options, the overall effectiveness of depression treatment remains unsatisfactory. Only about half of all patients respond adequately to initial antidepressant therapy, and depending on the study, complete remission cannot be achieved in up to two-thirds [2, 3]. Guideline-based depression treatment aims to increase therapeutic effectiveness by synthesizing and selecting current knowledge. Initial control studies were able to show that guideline-based treatment of unipolar depression does indeed lead to a significant increase in response and remission rates [4–6]. The recommendations presented below are based on the treatment recommendations [7] jointly developed by the Swiss Society of Psychiatry and Psychotherapy (SGPP), the Swiss Society of Anxiety and Depression (SGAD), and the Swiss Society of Biological Psychiatry (SGBP). They are based on the international guideline of the World Federation of Societies of Biological Psychiatry (WFSB) [8, 9] and the S3 guideline/national care guideline of the German Society for Psychiatry, Psychotherapy and Neurology (DGPPN 2009).

The acute treatment of depressive episodes

Any therapeutic intervention must be preceded by a detailed diagnostic workup. The depressive episode is defined in terms of severity according to the criteria of the International Classification of Diseases (ICD-10, WHO 1992). Further, the presence of other depressive or manic episodes in the history must be checked. Other mental or somatic illnesses must be recorded or ruled out. Special attention should be paid to possible depressiogenic factors, such as psychosocial stress, medication, or addiction. Following the diagnosis, a treatment plan should be developed together with the patient. This must take into account the severity of the current episode, the course of the disease, the nature and success of previous therapies, and patient preferences. Close collaboration between the psychiatrist and the general practitioner or physicians from other disciplines is of great importance, especially in cases of treatment resistance, complex courses, suicidality and comorbidities. Modern psychiatric depression treatment follows the claim to take into account specific medical and psychological conditions of the individual patient, to understand them better by including the social context and thus to ensure the best possible therapy. The goal of treatment is complete remission of symptoms.

Treatment methods according to severity

In a mild depressive episode, active-waiting support may be sufficient. However, a recheck of symptoms should be done within two weeks. Psychotherapy or pharmacotherapy may be considered here if symptoms persist or the patient explicitly requests it. In any case, the patient should be informed about the symptoms, course and treatment of depression in the course of psychoeducation. Either psychotherapeutic or pharmacologic treatment, or a combination, should be provided for moderately severe depressive episodes. In acute major depression, psychotherapy and pharmacotherapy should be combined. For outpatients with moderate to severe depressive episodes, psychotherapy should be offered on par with pharmacotherapy if monotherapy is the goal. Meta-analyses have shown that the combination of psychotherapy and pharmacotherapy is more effective than the respective therapies alone [10, 11].

Psychotherapy

The best evaluated psychotherapeutic procedures for the treatment of acute depression are Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) and Interpersonal Psychotherapy (IPT). Both procedures have been shown in meta-analyses to be well efficacious and similarly effective for mild to severe depression, with lower efficacy for chronicized courses [12, 13]. For the specific treatment of chronic depression, the Cognitive Behavioral-Analysis System of Psychotherapy (CBASP) is suitable and has been evaluated in clinical trials [14, 15]. Other clinically established methods are systemic therapy, depth psychological and analytical psychotherapy, and conversational psychotherapy. Scientific studies demonstrating the efficacy of these psychotherapy methods are somewhat rare, which is why the clinical evidence of their effectiveness is not questioned here.

Regardless of the psychotherapeutic orientation, the establishment of a sustainable therapeutic relationship is considered one of the most important predictors of therapeutic success. He is thus at the center of the therapeutic work [16]. General goals of psychotherapeutic depression treatment are shown in Table 1. Depression-triggering and -maintaining factors should be identified and – if possible – corrected. Together, affects such as guilt, shame, grief, and anger should be explored, reflected upon, and worked through. The patient’s relatives are to be involved in the treatment process and resources are to be strengthened. Open and regular assessment of suicidality is particularly important.

Somatic therapies

Treatment with antidepressants is considered the standard of medication for depression, especially for moderate or severe episodes. In addition, other somatic therapy methods have been developed in recent decades. Here, electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) in particular has become established for the treatment of treatment-resistant depression.

Psychopharmacotherapy

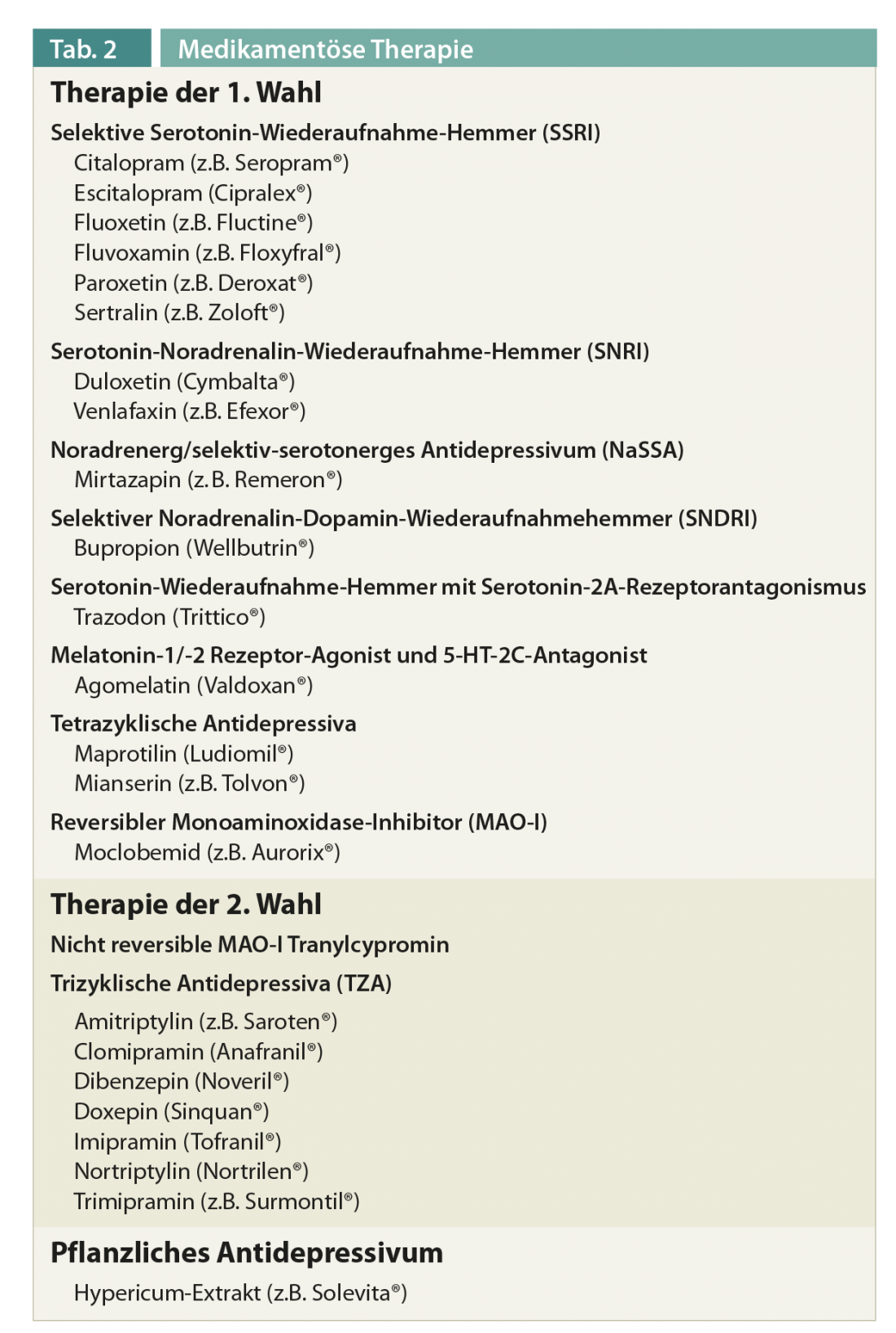

A large number of drugs from various substance groups are available for the pharmacological treatment of unipolar depression (Table 2). The approved antidepressants differ little in their antidepressant potency [18]. The general side effect profile and individual tolerability are therefore of decisive importance for the selection of a preparation. Side effects such as increased drive or sedation can be used therapeutically. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) are considered to be the first-choice therapy, mainly because of their favorable efficacy/side-effect profile. Adherence-limiting side effects with these preparations include (usually transient) sexual dysfunction and internal agitation. In addition, there are the newer selective serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs), a noradrenergic/selective serotonergic antidepressant (NaSSA), a selective norepinephrine-dopamine reuptake inhibitor (SNDRI), a serotonin reuptake inhibitor with serotonin 2A receptor antagonism, a melatonin 1/-2 receptor agonist and 5-HT-2C antagonist, and two tetracyclic antidepressants and a reversible monoamine oxidase inhibitor (MAO-I). Older medications, such as the nonreversible MAO-I tranylcypromine or tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs), are used less frequently, or as a second choice, or for special indications because of their less favorable side effect profiles.

As a herbal antidepressant, St. John’s wort is approved in Switzerland for mild to moderate depressive episodes. An initial improvement in symptoms should occur within two weeks if the dose is sufficient. If a sufficient antidepressant effect has not occurred after four weeks of treatment and a dose increase if necessary, treatment optimization should be considered. Three principal strategies can be considered for this purpose:

- Switching to an antidepressant of a different substance class

- Combination of two antidepressants of different classes

- Augmentation with another substance.

The best empirical evidence is for augmentation with lithium, which is therefore considered the first choice when an antidepressant fails to work. Recently, augmentation with an atypical antipsychotic has also been recommended. Thyroid hormones (T3>T4) can also be used for augmentation [19]. Detailed information on the above treatment algorithms can be found at http://www.psychiatrie.ch/index-sgpp-de.php?frameset=36.

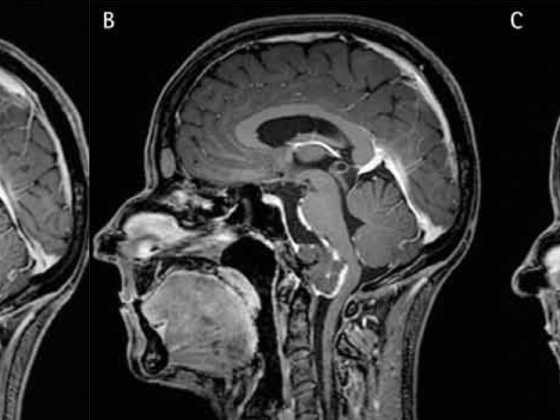

Electroconvulsive therapy

Electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) is considered one of the most effective antidepressant treatments available. Its effect has been demonstrated many times for both bipolar and unipolar depression and meta-analytically confirmed [20]. The advantages of ECT are its rapid onset of action and its applicability in complicated situations, such as pregnancy. Indications are psychotic and therapy-resistant depression (>2 unsuccessful attempts at medication) and severe suicidal tendencies. The main side effect reported is transient memory impairment [21]. Since the effect of ECT is rapid but also wears off quickly, maintenance therapy with ECT and/or pharmacotherapy is necessary (DGPPN statement on ECT: www.dgppn.de/fileadmin/user_upload/_medien/download/pdf/stellungnahmen/2012/stn-2012-06-07-elektrokonvulsionstherapie.pdf).

Magnetic Convulsive Therapy (MST) was developed as an alternative to ECT. Magnetic rather than electrical induction of convulsions should result in a lower expression of cognitive side effects with comparable antidepressant efficacy. However, the data available on this form of treatment do not yet allow recommendations to be made [22].

Other somatic therapies

A rapid antidepressant effect can also be achieved by complete or partial sleep deprivation. This procedure is particularly suitable for inpatient treatment. Similar to ECT, the antidepressant effect lasts only a short time in most cases. In the presence of seasonal depressive disorder, light therapy is the treatment of choice. When using a therapy lamp suitable for this purpose, the effect corresponds to that of SSRI treatment.

Several studies have demonstrated the antidepressant efficacy of stimulation techniques such as deep brain stimulation (DBS), vagus nerve stimulation (VNS), and transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) [23]. However, the data situation for these procedures is still too unclear to make definitive recommendations.

Maintenance therapy

Following remission, maintenance therapy must be given to prevent recurrence. If remission was achieved with an antidepressant, the drug should be continued at the same dose for a period of at least four to nine months. Residual symptoms should also be treated proactively and adequately with medication, as they are predictors of increased risk of relapse. Because discontinuation symptoms may be difficult to distinguish from relapse, slow tapering (at least four weeks) of the drug must occur after the remission-stabilizing treatment has ended.

Recurrence prophylaxis

After maintenance therapy, longer-term relapse prophylaxis should be given if the patient has already suffered two or more depressive episodes with significant functional impairment. For this purpose, the antidepressant should be taken in the remission dose for a period of at least two years. In the presence of severe and/or persistent suicidality, recurrence prophylactic treatment with lithium should also be considered. In the presence of pronounced risk factors such as comorbidities or persistent and severe psychosocial distress, recurrence prophylaxis should be considered >2 years.

New approaches in depression treatment

The unsatisfactory response rates to antidepressant therapies have led to a large scientific effort to biologically characterize subgroups of patients with depressive disorders in recent decades. By identifying so-called biomarkers, a more specific and individualized treatment – a personalized therapy – is to be achieved in this way. For this purpose, changes in the functional imaging of depressed patients as well as the hormonal stress axis and its genetic correlates were mainly investigated. Although it was possible to collect individual trend-setting findings, they have not (yet) found a practicable entry into the psychiatric clinic. [24]. The investigation of new molecular targets for drug treatment of depression is another focus of current research. Modulation of the glutamate system, e.g. with the N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptor antagonist ketamine, and the stress axis seem to be the most promising here. However, the neurosteroid and GABA systems are also currently being discussed as targets for novel antidepressants [25].

Literature:

- Kessler RC, et al: Jama 2003; 289: 3095-3105.

- Copper DJ: Dialogues Clin Neurosci 2005; 7: 191-205.

- Rush AJ, et al: Am J Psychiatry 2006; 163: 1905-1917.

- Adli M, Berghofer A, Linden M, Helmchen H, Muller-Oerlinghausen B, Mackert A, et al: J Clin Psychiatry 2002; 63: 782-790.

- Kohler S, Hoffmann S, Unger T, Steinacher B, Fydrich T: Int J Psychiatry Clin Pract 2012; 16: 103-112.

- Trivedi MH, et al: Arch Gen Psychiatry 2004; 61: 669-680.

- Holsboer-Trachsler E, Hättenschwiler J, Beck J, Brand S, Hemmeter UM, Keck ME, et al: Switzerland Med Forum 2010; 10: 802-809.

- Bauer M, Whybrow PC, Angst J, Versiani M, Moller HJ: World J Biol Psychiatry 2002; 3: 5-43.

- Bauer M, Whybrow PC, Angst J, Versiani M, Moller HJ: World J Biol Psychiatry 2002; 3: 69-86.

- Cuijpers P, Dekker J, Hollon SD, Andersson G: J Clin Psychiatry 2009; 70: 1219-1229.

- Cuijpers P, van Straten A, Warmerdam L, Andersson G: Depress Anxiety 2009; 26: 279-288.

- Cuijpers P, Clignet F, van Meijel B, van Straten A, Li J, Andersson G: Clin Psychol Rev 2011; 31: 353-360.

- Jakobsen JC, Hansen JL, Simonsen S, Simonsen E, Gluud C: Psychol Med 2012; 42: 1343-1357.

- Keller MB, et al: N Engl J Med 2000; 342: 1462-1470.

- Schatzberg AF, Rush AJ, Arnow BA, Banks PL, Blalock JA, Borian FE, et al: Arch Gen Psychiatry 2005; 62: 513-520.

- Ardito RB, Rabellino D: Front Psychol 2011; 2: 270.

- Engel GL: Science 1977; 196: 129-136.

- Cipriani A, Furukawa TA, Salanti G, Geddes JR, Higgins JP, Churchill R, et al: Lancet 2009; 373: 746-758.

- Benkert O, Hippius H: Compendium of Psychiatric Pharmacotherapy, 8th ed. Berlin, Heidelberg, New York: Springer Verlag 2011.

- Dierckx B, Heijnen WT, van den Broek WW, Birkenhager TK: Bipolar Disord 2012; 14: 146-150.

- Payne NA, Prudic J: J Psychiatr Pract 2009; 15: 346-368.

- Allan CL, Ebmeier KP: Int Rev Psychiatry 2011; 23: 400-412.

- Schonfeldt-Lecuona C, Cardenas-Morales L, Freudenmann RW, Kammer T, Herwig U: Restor Neurol Neurosci 2010; 28: 569-576.

- Bosch OG, Seifritz E, Wetter TC: World J Biol Psychiatry 2012.

- Bosch OG, Quednow BB, Seifritz E, Wetter TC: J Psychopharmacol 2012; 26: 618-628.

InFo NEUROLOGY & PSYCHIATRY 2013; (11)1: 4-8.