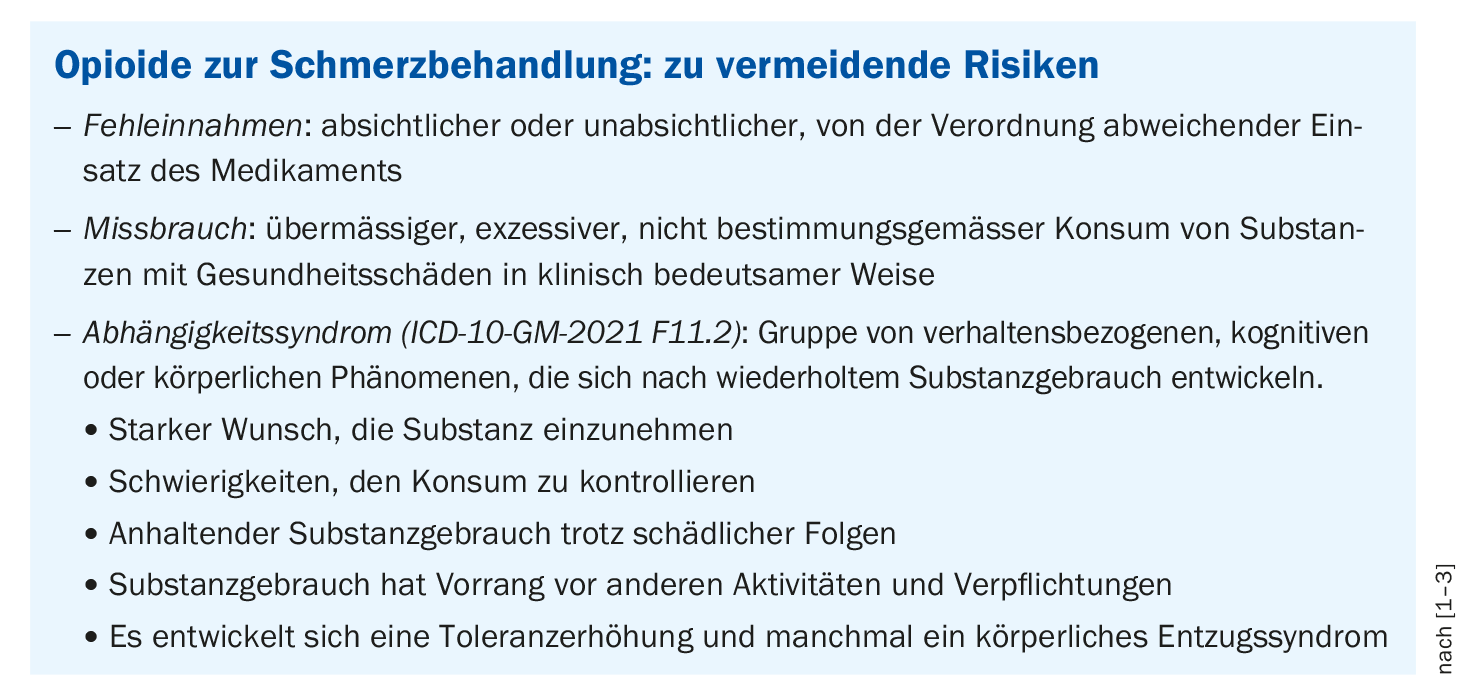

Opioid analgesics are an important drug therapy option for chronic pain, and care must be taken to use them as directed. To gain insight into “real world” care practices of long-term opioid analgesic use, the large-scale German study “Op-US” was launched. Survey and routine data were combined to shed light on the current care situation from different perspectives.

This study aims to fill a research gap regarding the long-term use of opioid analgesics for chronic nontumor-related pain by examining risk factors for harmful opioid use and barriers to guideline-based care from the perspective of patients and clinicians [1]. The fact that the use of opioid analgesics can lead to physical dependence and how this can be counteracted is addressed, among other things, in the current S3 guideline on the long-term use of opioids for chronic non-tumor-related pain (LONTS) [2]. This was also one of the focal points of the “Op-US” study. On the occasion of the German Pain Congress, the three subprojects summarized below were presented [1].

Expert interviews on risk factors for harmful opioid use.

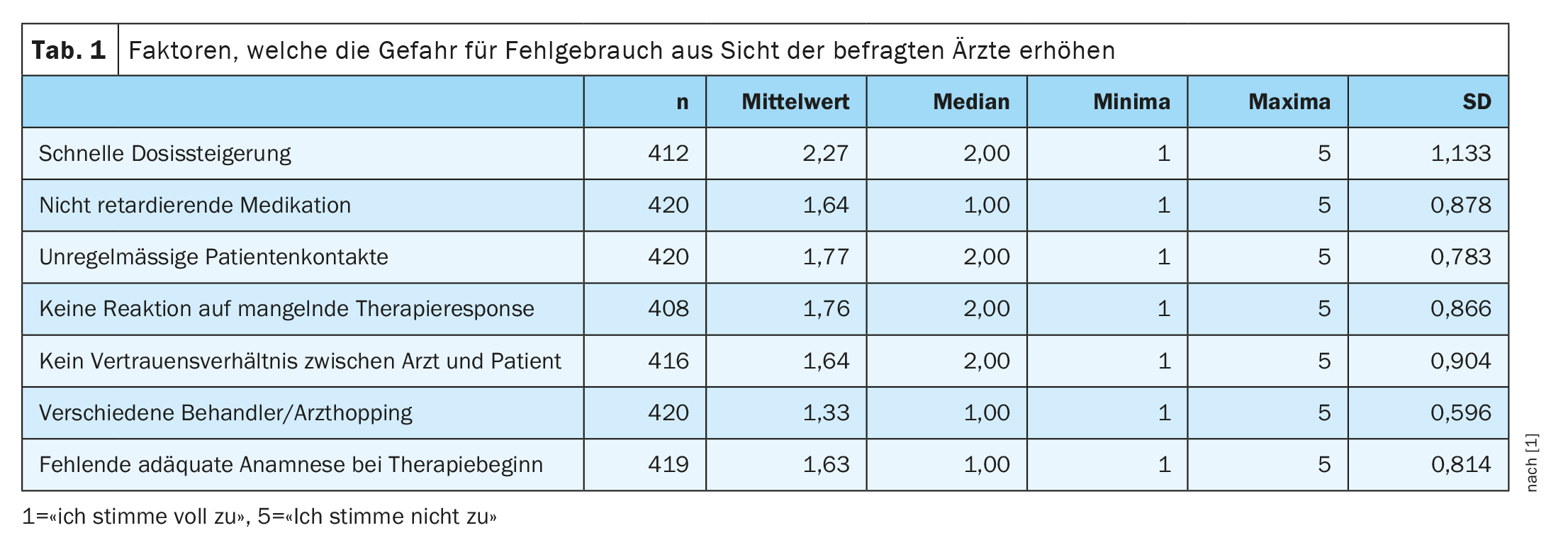

Dr. Carina Abels, research associate at the University of Duisburg-Essen, presented the results of a subproject in which eight interviews with primary care physicians, orthopedists, neurologists, and pain physicians were conducted in the period from December 2020 to January 2021 and analyzed based on Mayring and Kuchartz’s qualitative content analysis. “We looked at what are aspects that increase the risk of abuse, misuse, or addiction,” she said [1].

An overview of the general risk factors for improper use detected in the process:

- Underlying mental illnesses

- Pre-existing dependency disorders

- Rapid dose increases, non-retardant (as-needed) medication.

- Irregular patient contacts (response to lack of therapy response).

- No relationship of trust between doctor and patient

- Different treatment providers (“doctor hopping”)

- Lack of adequate medical history and education at the start of therapy

- Patient’s lack of ability/knowledge to take medication correctly

- Treatment is not provided by care providers trained in pain management or the guideline is not applied

It was found that, in addition to patients with high opioid doses, subgroups with mental health comorbidities or existing addictive disorders, as well as those with comorbidities that would not allow the prescription of other medications such as nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), are particularly at risk for abuse, misuse, and dependence

What are factors that make it easier to identify patients at risk? According to the researchers’ analyses, these include regular patient contacts planned with an appropriate time frame and the use of pain questionnaires. In addition, the frequency of prescribing should be reviewed for each prescription. Special attention should be paid to patients who have been transferred from another practitioner, as important preliminary information may be missing. While these aspects seem obvious at first glance, a look at the reality of everyday practice shows that there are some hurdles. One of the care providers interviewed made the following statement [1]: “So when you approach someone and say ‘So listen, we need to talk about the opioid dose’. Then you know that can now take half an hour and leave an angry patient and ten unnerved aides because this has now taken too long”. While primary care physicians indicated that they refer patients with difficult-to-treat pain conditions to pain physicians, they reported that they are often not involved in the treatment process until many treatment options have already been exhausted and opioid therapy is the only remaining option [1],

Barriers to guideline-based care from the perspective of the medical profession

The subproject presented by Nils Frederik Schrader, M.Sc, University of Duisburg-Essen, focuses on quantifying the physician perspective [1]. To this end, a physician survey was conducted as a complementary perspective on long-term therapy with opioid analgesics for chronic nontumor-related pain in Germany. This was an anonymous cross-sectional survey, which was conducted in September 2021. A total of 1300 SHI-accredited physicians working in outpatient care and 554 members of the Professional Association of Physicians and Psychological Psychotherapists in Pain and Palliative Medicine in Germany were surveyed.

In particular, physicians cited psychological comorbidities and existing addictive disorders as patient-related risk factors for harmful use of opioids. The risk factors and groups are largely consistent with the S3 guideline for medication-related disorders, the speaker explained, with these aspects standing out in the survey (Table 1): non-retardant medication, younger age, mental comorbidities and existing addictions, physician hopping [1,3]. The majority of health care providers surveyed were in favor of multimodal therapy [1]. Thus, more than 90% of the survey participants are of the opinion that physiotherapeutic measures are useful. One conclusion of this substudy is that there is a discrepancy between the assessment of the need for and the feasibility of implementing further therapeutic measures. In terms of physical therapy prescribing, this is predominantly attributed to regulatory constraints and shortages of specialists.

Analysis of patient data from routine care

Anja Niemann, also from the Department of Medical Management, University of Duisburg-Essen, presented a subproject in which patient data from a large cohort of health insurance patients in Germany were analyzed [1]. Patients insured over 17 years of age with opioid prescriptions in at least two quarters (2018-2019) were included. Exclusion criteria included cancer diagnoses and palliative care. The total of 113,476 selected study participants (mean age 71.8 years) were followed over a two-year period, and approximately three-quarters of the total sample were female.

At 44%, there was a strikingly high proportion of insureds with a diagnosis of an affective disorder in temporal relation to the prescription of opioid analgesics. Whereas there are comparable findings in the literature. Thus, Häuser et al. correlation with affective disorder in 39% of subjects on >120 mg morphine equivalent/day and 49% on higher doses [4]. Regarding the contraindications formulated in the guideline, the prescribing practice analyzed in this substudy shows a certain contradiction. On the one hand, it is discussed whether this discrepancy can be explained by the reality of care for patients for whom all other treatment options have been exhausted, and on the other hand, the question is raised whether the guideline really targets all ICD10 codes F32 to F34 or only severe manifestations of affective disorders [1,2]. There are several explanations for a link between chronic pain and depression [1,5,6]. Thus, on the one hand, chronic pain can trigger depression and, on the other hand, a depressive disorder is often accompanied by an altered perception of pain. Pain and depression are thus mutually reinforcing. Thus, pain threshold and pain tolerance decrease when the psyche is affected.

Congress: German Pain Congress

Literature:

- Opioid analgesics – Investigation into development trends in the provision of care for non-tumor related pain (Op-US), SY01, German Pain Congress, 20.10.2022.

- S3 Guideline Long-Term Use of Opioids for Chronic Non-Tumor Related Pain (LONTS), Registry Number 145-003, 2020, https://register.awmf.org/de/leitlinien/detail/145-003,(last accessed Jan 03, 2023).

- S3 Guideline Drug-Related Disorders, Registry Number 038 – 025 , https://register.awmf.org/de/leitlinien/detail/038-025,(last accessed Jan. 03, 2023).

- Häuser W, et al: Guideline-recommended vs. high-dose long-term opioid therapy for chronic noncancer pain is associated with better health outcomes: data from a representative sample of the German population. PAIN 2018; 159(1): 85-91.

- American Psychological Association: Clinical practice guideline for the treatment of depression across three age cohorts. www.apa.org/depression-guideline,(last accessed Jan. 03, 2023).

- S3 Guideline/National Health Care Guideline Unipolar Depression, 2015, 2nd edition, long version. DOI 10.6101/AZQ/000364.

- Pharmawiki, www.pharmawiki.ch/wiki/index.php?wiki=opioide,(last accessed Jan. 03, 2023).

HAUSARZT PRAXIS 2023; 18(1): 26