Lyme disease is the most common tick-borne infectious disease in Europe. If Lyme disease is detected early, it can be treated well with antibiotics. A typical early-stage skin condition is erythema migrans, which spreads around the sting days to weeks after infection. Less common cutaneous manifestations include Borrelia lymphocytoma and circumscritic scleroderma.

Ticks are widespread in Switzerland, with the common wood tick (Ixodes ricinus) being the most common tick species in this country. It occurs up to 2000 m.a.s.l. and is mainly active from March to November. Ixodes ricinus can be carriers of the pathogens of Lyme disease or early summer meningoencephalitis [1]. Bacterial infection with Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato can lead to Lyme disease, which in humans can present as disease of the skin, joints, heart, CNS, and eyes [1,2]. Unrecognized or inadequately treated, permanent sequelae may result [1].

| Erythema migrans: a visual diagnosis Erythema migrans is present in almost 90% of all cases of Lyme disease; in Switzerland this is around 6700-11 000 cases per year. Erythema migrans is a clinical diagnosis; serology is initially unnecessary, since usually no changes are detectable in the blood at this early stage. The redness of the skin spreads slowly centrifugally over a period of days to weeks and fades centrally as it progresses. For reliable detection, the diameter should be ≥5 cm. If erythema migrans is suspected, antibiotic treatment should be prescribed. Without antibiotic therapy, approximately 40-60% of patients with erythema migrans develop Borrelia arthritis, approximately 10-15% develop neuroborreliosis, and up to 5% develop cardiac manifestations. to [2,3] |

While early erythema migrans is a clinical diagnosis (box), all further manifestations require confirmation by antibody detection. In addition to erythema migrans, other cutaneous manifestations may occur during the course of Lyme disease. A research team described skin manifestations at different stages of disease in a case series in children [4]. All of the cases described below are from Karol Jonscher Hospital at the University of

Medical Sciences, Poznań (Poland).

Case 1: atypical form of multiple erythema migrans

The 4-year-old girl came to the emergency room accompanied by her parents. For four weeks, the child had had skin lesions that had appeared on both lower limbs simultaneously and had gradually spread to the lower abdomen.

History: Six weeks before presentation to the emergency department, the girl had been bitten by a tick in the groin. The skin lesions were not accompanied by worsening of well-being and no fever occurred. Because of suspected Lyme disease, the child was referred to the hospital’s infectious disease outpatient clinic.

Clinical findings: the physician noted painful, brownish, raised lesions on the back of the legs accompanied by surrounding redness that gradually increased (Fig. 1) [4]. Hardening and tenderness were present over the lesions, and local lymphadenopathy was noted in the popliteal area. In addition, the girl had spots on the lower abdomen. Neither joint swelling nor itching occurred. The rest of the physical examination was unremarkable.

Laboratory analysis: Five weeks after the appearance of the first skin lesions, a complete blood count was done with a peripheral blood smear that was found to be normal. Concentrations of C-reactive protein (CRP), fibrinogen, and coagulation factors were also within the normal range. An enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) for Borrelia burgdorferi was performed: IgM and IgG concentrations were elevated at 82.66 AU/mL and 44.3 AU/mL, respectively (cut-off for positive tests: above 22 AU/mL). A Western blot (WB) revealed positive IgM antibodies against OspC (p25) of Borrelia afzeli, B. burgdorferi sensu stricto and B. garinii and against flagellin (p41), and positive IgG antibodies against OspC of Borrelia afzeli, B. burgdorferi sensu stricto and B. garinii, flagellin (p41) from B. afzeli and antigen VIsE from B. garinii and B. burgdorferi sensu stricto

Diagnosis: The atypical form of multiple erythema migrans was diagnosed.

Treatment and subsequent course: treatment with amoxicillin at a dose of 50 mg/kg body weight/day was initiated immediately [5,6].

After one week, the lesions had not developed beyond their original size, and after two weeks there was a slight improvement: the erythema on the abdomen had decreased, and the purple lesions on the legs were less intense and painful. Antibiotic treatment was continued for a total of four weeks until the lesions clinically resolved. The appearance of the skin presented unchanged at the pediatric examination of the child performed six weeks after the end of therapy.

| ANA=antinuclear antibodies ANCA=anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies CLIA=Chemiluminescence Immunoassay ELISA=Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay Ig=immunoglobulin OspC=outer surface protein PCR=Polymerase Chain Reaction |

Case 2: Borrelia lymphocytoma

The 11-year-old boy was referred to the Infectious Disease Outpatient Clinic in March 2021 for suspected Lyme lymphocytoma.

History: At a November 2020 appointment, the parents noted asymmetry of the ear and enlargement of the right auricle. The family physician consulted recommended topical therapy with mupirocin ointment. Since there was no improvement, the parents presented the boy to the otolaryngologist, who referred the child to the Department of Laryngology for a biopsy. The biopsy material taken showed a skin fragment with abundant lymphocytic infiltration in the stroma, lymphoid cells in the form of T (CD3+) and B (CD20+) lymphocytes, and some polyclonal plasma cells (lambda-positive, kappa-positive).

Clinical Findings: The auricle of the right ear was larger and hard, clear, bluish-red swellings manifested in the area of the earlobe. This was a painless lesion (Fig. 2A) [4]. In addition, the skin was unremarkable, without abnormal erythematous changes. Peripheral lymph nodes were neither enlarged nor painful.

Laboratory Analyses: The diagnosis was confirmed by ELISA test, detecting positive IgG class antibodies to Borrelia burgdorferi (IgG-95 AU/mL; positive result above 22 AU/mL; IgM-17 AU/mL; positive above 22 AU/mL)**. The result was confirmed by Western blot (IgG positive for: p100, VIsE, p41, p39, OspC B antigens of B. afzeli and p18 of B. garinii)#.

** CLIA method; liaison system; DiaSorin SpA, Saluggia, Italy

# EUROLINE Borrelia-RN-AT; Euroimmun AG, PerkinElmer, Inc., Waltham, MA, USA

Diagnosis: Borrelia lymphocytoma (lymphadenosis cutis benigna) was diagnosed.

Treatment and further course: The patient was treated with oral amoxicillin at a dose of 50 mg/kg body weight/day [5,6]. A follow-up examination at the third week of treatment showed a marked decrease in the lesion in the earlobe (Fig. 2B) [4]. Treatment was continued for up to 28 days. A recheck six weeks after the start of antibiotic treatment showed complete resolution of the skin lesions (Fig. 2C) [4].

Case 3: Circumscribed scleroderma (morphea).

An 8-year-old girl presented to the infectious disease outpatient clinic because of indurated plaques on her right lower leg that had been present for seven months.

Anamnesis: Since the father was a forester, the child often spent time in the forest. Both parents suffered from chronic Lyme disease. In December 2021, the child developed a bluish-red, limited induration of the skin with a diameter of more than 7 cm, accompanied by itching.

In the center of the lesion, the skin was thinner and had atrophic features. Because of suspected allergy, the girl was given antihistamines, but they had no therapeutic effect. A dermatologist was consulted about two months after the appearance of the skin lesions. He initially prescribed local treatment with a topical steroid (aclometasone), but there was no improvement. Four months after the appearance of the skin lesions, the child began to complain of pain in the joints and muscles of both legs.

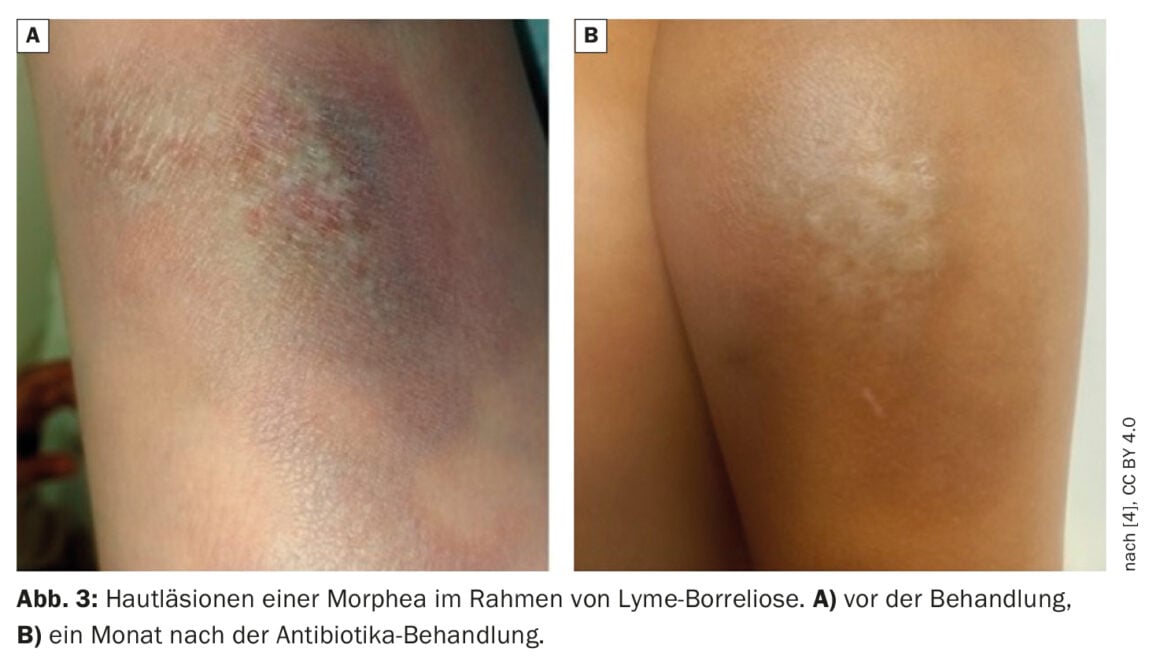

Clinical Findings: At consultation, the infectious disease specialist noted diffuse, atrophic, hypopigmented, induced plaques on the left lower leg. Epidermal defects were visible in the central areas of sclerosis (Fig. 3A).

Laboratory analyses: Serological diagnostics revealed an increased concentration of Borrelia burgdorferi antibodies in the ELISA test (IgM-26.44 AU/mL; IgG-78.01 AU/mL; positive result above 22 AU/mL)**. The Western blot was also positive for IgM and IgG, positive antibodies against OspC (p25) of B. afzeli, B. burgdorferi sensu stricto and B. garinii as well as for antibodies against flagellin (p41) of B. afzeli and for antibodies against VIsE antigen of B. garinii, B. burgdorferi sensu stricto and B. afzeli in the IgG class).#

** CLIA method; Liaison System; DiaSorin SpA, Saluggia, Italy

# EUROLINE Borrelia-RN-AT; Euroimmun AG, PerkinElmer, Inc, Waltham, MA, USA.

Diagnosis: Oral cefuroxime was prescribed at a dose of 30 mg/kg body weight/day [5,6]. In addition, the girl was referred to the hospital for a skin biopsy. During the stay in the infectious disease ward, various laboratory tests were performed, which showed no abnormalities: leukocyte count, 4.57 ×109/L; hemoglobin concentration, 11.6 g/dL; platelet count, 307 ×103/L; CRP, 0.02 mg/dL; erythrocyte sedimentation rate, 4 mm/h; total serum IgG concentration, 1030 mg/dL; rheumatoid factor, negative. No ANA or ANCA were detected in the serum and the ELISA test for viral infections (hepatitis B and C, cytomegalovirus, Epstein-Barr virus) was negative. A PCR test was performed on the skin biopsy specimen, but no Borrelia burgdorferi DNAwas detected. Histopathologic examination of the skin biopsy section revealed a thin epidermis with vacuolization of the basal layer and numerous melanophages beneath the epidermis. The deeper layers of the skin contained small collections of lymphocytes surrounded by a dense, homogeneous, eosinophilic stroma.

In summary, Lyme disease was initially diagnosed and the skin appearance corresponding to morphea was classified as localized scleroderma caused by B. burgdorferi .

Treatment and further course: Antibiotic therapy with oral cefuroxime was continued for four weeks [5,6]. A follow-up examination two months after the end of antibiotic therapy showed local improvement of the skin condition and relief of itching. The area of the former plaque was covered with a dry layer of epidermis without induration (Fig. 3B).

Literature:

- “Tick-borne diseases,” www.bag.admin.ch/bag/de/home/krankheiten/krankheiten-im-ueberblick/zeckenuebertragene-krankheiten.html,(last accessed 04/11/2023).

- “Lyme Arthritis in Children and Adolescents,

www.springermedizin.de/emedpedia/paediatrische-rheumatologie/lyme-arthritis-bei-kindern-und-jugendlichen?epediaDoi=10.1007%2F978-3-662-

60411-3_36, (last accessed 11.04.2023) - Lanz C, et al: Rational management of a modern epidemic – Part 1. Lyme disease: epidemiology, erythema migrans, 2022/04, https://primary-hospital-care.ch/article/doi/phc-f.2022.10573, (last accessed 11/04/2023).

- Myszkowska-Torz A, et al: Cutaneous Manifestations of Lyme Borreliosis in Children – A Case Series and Review. Life. 2023; 13(1):72.

www.mdpi.com/2075-1729/13/1/72,(last accessed 04/11/2023) - Pancewicz SA, et al: Polish Society of Epidemiology and Infectious Diseases. Diagnosis and treatment of tick-borne diseases: recommendations of the Polish Society of Epidemiology and Infectious Diseases. Przegl Epidemiol 2015; 69: 421-428.

- Arnez M, et al: Solitary and multiple erythema migrans in children: Comparison of demographic, clinical and laboratory findings. Infection 2003; 31: 404-409.

DERMATOLOGY PRACTICE 2023; 33(2): 36-38