In hypoxemia, the partial pressure of oxygen or oxygen content in arterial blood is decreased, while in hypoxia there is an undersupply of oxygen to tissues and organs. Tissue hypoxia can be divided into hypoxemic, anemic, stagnant, and histotoxic (e.g., cyanide poisoning). Hypoxemia is usually diagnosed in adults for a partial pressure of oxygen, PaO2 <60 mmHg and a SaO 2 <90% is defined.

In hypoxemia, the partial pressure of oxygen or oxygen content in arterial blood is decreased, while in hypoxia there is an undersupply of oxygen to tissues and organs. Tissue hypoxia can be divided into hypoxemic, anemic, stagnant, and histotoxic (e.g., cyanide poisoning). Hypoxemia is usually defined in adults for a partial pressure of oxygen, PaO2 <60 mmHg and a SaO2 <90% [1].

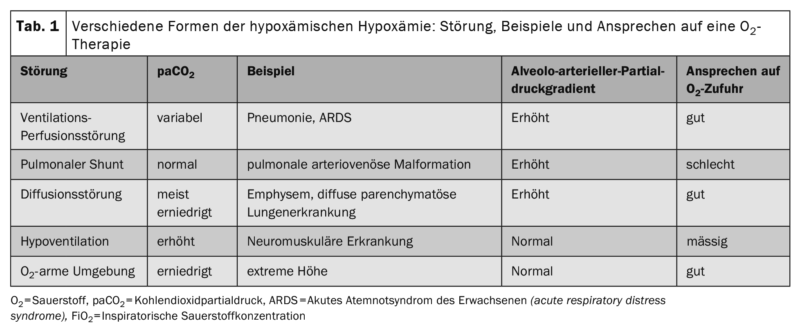

Oxygen therapy is used to correct hypoxemic hypoxia, which occurs when the partial pressure of oxygen in the blood is decreased. This may be caused by a stay at high altitude, a right/left shunt, pronounced ventilation/perfusion inhomogeneities in the lungs, diffusion disorders, or alveolar hypoventilation (table 1).

“Respiratory insufficiency type 1” with decreased partial pressure of oxygen (PaO2) and normal or decreased partial pressure of carbon dioxide (PaCO2) is due to hypoxemic hypoxia in the sense of hypoxemic respiratory insufficiency. Hypercapnic respiratory failure (type 2 respiratory failure) is present when paCO2 is elevated ≥45 mmHg, with possibly consecutive decreased values of SaO2 and pO2.

Important: The underlying causes of hypoxemia should be identified and treated. Oxygen should be administered to treat hypoxemia, not respiratory distress.

For practice

- In addition to oxygen therapy, general measures such as positioning to improve oxygenation are useful in acute hypoxemia. In some patients, upright upper body positioning may improve oxygenation. Acute respiratory failure during flat positioning has been described in morbidly obese patients (BMI >50 kg/m2) [2].

- There are no RCTs for a beneficial effect of prone positioning in awake, spontaneously breathing hypoxemic patients. Until the creation of this guideline, there were individual case series for COVID-19 patients that described a positive effect (“self-proning”).

- For the treatment and prevention of vena cava compression syndrome, a left lateral position should be adopted by pregnant women with hypoxemia.

- For respiratory distress without hypoxemia, palliative care initially uses non-drug measures: relaxation exercises, cooling of the face, airflow through a handheld ventilator, and walking aids.

- The use of opioids for respiratory distress has been well studied and is a proven effective drug intervention for respiratory distress without hypoxemia.

Oxygen therapy

Oxygen is a drug and should be prescribed only when indicated. Precise data on how frequently oxygen is used in emergency and acute medicine in Germany are not yet available [3]. To date, numerous randomized-controlled trials and systematic reviews have been published on the target areas of oxygen therapy. Most randomized trials have compared normoxemia versus normal oxygen target ranges (hypoxemia). No randomized trials are available on studies of permissive hypoxemia Me in adults, so it remains unclear at what lower limit of hypoxia oxygen therapy is clinically helpful. In acute medicine, oxygen is still used rather uncritically in Germany due to the lack of a guideline, e.g. in patients with respiratory distress without the presence of hypoxemia. While an S3 guideline on long-term oxygen therapy has been available for many years, a German-language S3 guideline on oxygen in the acute setting in adults was published for the first time this year [4].

Clinical assessment of hypoxemia

When assessing patients in respiratory distress, respiratory rate, pulse rate, blood pressure, temperature, and level of consciousness should be determined in addition to oxygen saturation.

The clinical examination of the critically ill patient should be guided by, among other things, the “ABC” of emergency medicine (A for airway [airway], B for ventilation [breathing], C for circulation [circulation]) [5]. The following physiologic variables should be collected during the initial evaluation of patients with respiratory distress and during continued observation of patients on oxygen:

- Oxygen saturation

- Breathing rate

- State of consciousness (e.g., classified as ACVPU: alert, confused, verbally responsive, pain responsive, unresponsive).

- Systolic blood pressure

- Temperature

- Heart rate

These so-called track-and-trigger systems are point scores of vital signs that serve as an early warning system of incipient or relevant changes. One example is the National Early warning score (NEWS2) [6]. In the NEWS2 system, points are assigned to the above 6 vital signs and additionally to the presence of oxygen therapy. The total NEWS2 score can range from 0 to 20 points, with clinically stable patients defined as having a score below 5. In addition to assessing patient stability, track-and-trigger systems have not shown superiority with respect to patient-relevant clinical outcomes in systematic reviews.

Important: Pulse oximetry should be available in all clinical situations where oxygen is used medically and should be used regularly to monitor oxygen therapy.

For practical use: In clinical practice, for arterial or capillary blood gas analyses, it is useful to record the pulsoximetric saturation at the time of sample collection in parallel with the arterial saturation. In case of large deviations between SpO2 and SaO2, a plausibility check is recommended. If a patient’s oxygen saturation is below the prescribed target range, first check the oxygen system and pulse oximetry for errors (e.g. sensor signal). Devices with pulse curve display (plethysmography) or signal quality display are useful for evaluating pulse oximetry. Determination of SpO2 is useful repetitively in all patients receiving O2 treatment. In patients with risk factors, continuous pulsoximetric monitoring may also be indicated. Pulse oximetry may overestimate oxygen saturation in patients due to the influence of dark skin color or in sickle cell crises. The trigger threshold for performing blood gas analysis should be set lower in patients with darker skin color. Training of medical staff on interpretation and limitations of pulse oximetry is useful. In combination with other vital signs (especially respiratory rate), pulse oximetry provides an important prognostic assessment especially of hospitalized patients (e.g. NEWS2 score) and under oxygen therapy (e.g. ROX index).

Blood gas analyses to monitor oxygen therapy should be performed under inpatient conditions in the following patient populations:

- critically ill patients, e.g. in shock or with metabolic disorders

- ventilated patients

- Patients with severe hypoxemia (over 6 l O2/min, or FiO2 over 0.4).

- Patients at risk for hypercapnia (e.g., COPD, severe asthma, obesity with BMI >40 kg/m2).

- Patients without a reliable pulse oximetry signal

For stable patients outside the indications mentioned, routine determination of blood gases should not be performed.

Important:

- It is not necessary to perform routine blood gas analyses in stable patients without critical illness or risk of hypercapnia. This applies as long as an oxygen flow rate of 6 l/min (or FiO2 >0.4) is not exceeded.

- In patients at risk of hypercapnia, blood gas analyses from arterial or arterialized blood are indicated under inpatient conditions.

- Blood gas analysis from arterialized capillary blood at the earlobe can be used in the inpatient setting for patient assessment outside of intensive care units.

Practical tip

A standard for capillary blood gas analysis is recommended. For preparation of capillary blood gas analyses, at least 5 minutes of constant O2 flow rate, at least 10 minutes of hyperemization, and at least 15 minutes of physical rest apply [7].

Both capillary blood gas analysis and pulse oximetry may underestimate arterial oxygen saturation. If SpO2 and SaO2 are measured simultaneously, oxygen therapy should be based on the higher of the two readings or an arterial blood gas analysis should be performed.

Venous blood gas analysis should not be used for monitoring oxygen therapy. Venous blood gas analysis can only exclude hypercapnia at a pvCO2 <45 mmHg.

Oxygen prescription

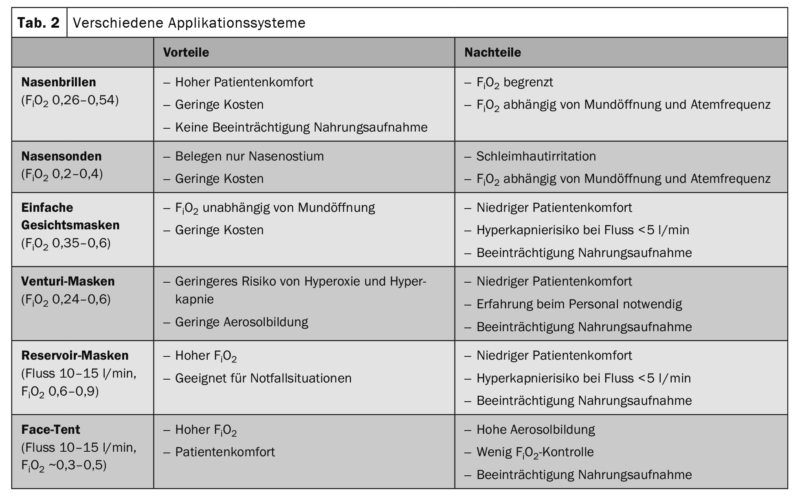

Oxygen should be applied, monitored and controlled by personnel trained in the field of oxygen therapy. Patients should be informed about oxygen therapy. Nasal cannulae should be used primarily for low O2 flow rates(i.e., <6 l/min), with low oxygen delivery venturi masks used as an alternative. Nasal cannulae/probes and venturi masks are preferred for oxygen application in acute care. When using venturi masks, observe minimum O2 flow rates according to manufacturer’s information. Do not use simple face masks or reservoir masks when there is a risk of hypercapnia and oxygen flow rates are less than 5 L/min.

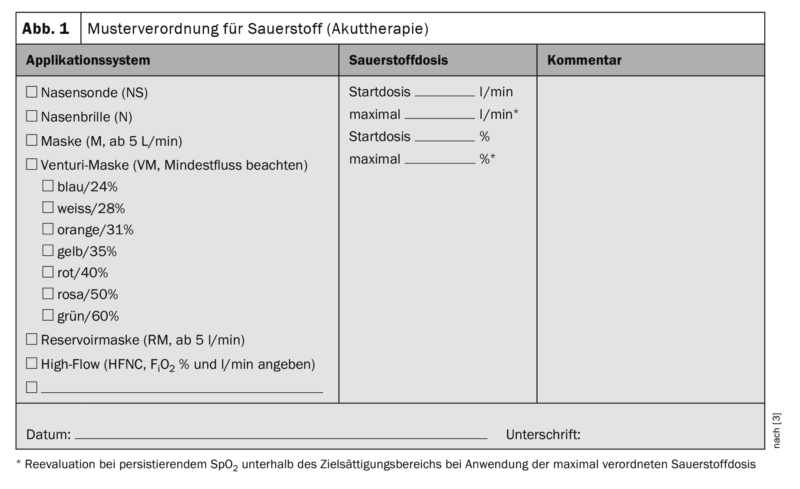

Oxygen should be prescribed by a physician for each inpatient, specifying a target range of oxygen saturation (Tab. 2) . When prescribing the delivery system (nasal probe/goggle, mask, venturi mask, reservoir mask, high-flow, etc.), O2 demand, breathing pattern, i.e., respiratory rate, depth of breath, mouth opening, and risk of hypercapnia should be considered [8]. Oxygen treatment must be ordered by a physician. The order should usefully include the type of application, amount of oxygen, target ranges of saturation and monitoring intervals (Fig. 1). In an emergency situation, oxygen should be given without a formal prescription and subsequently documented in writing. Reevaluation by physicians or specially trained personnel should be performed each time oxygen is prescribed. Under oxygen therapy, monitoring of vital signs is indicated at least every 6 hours. At flow rates above 6 l/min and under high-flow oxygen (HFNC), continuous monitoring of SpO2, pulse, and respiratory rate, as well as close monitoring of other vital signs (level of consciousness, blood pressure, body temperature) are recommended.

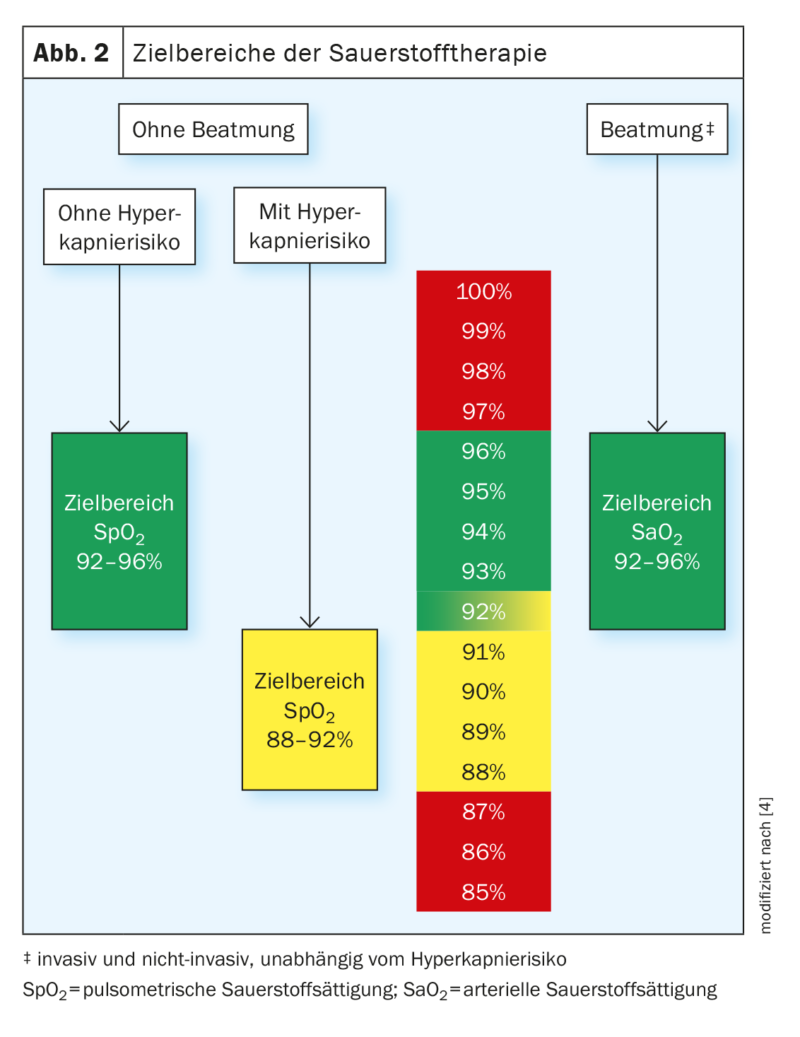

Oxygen therapy target range

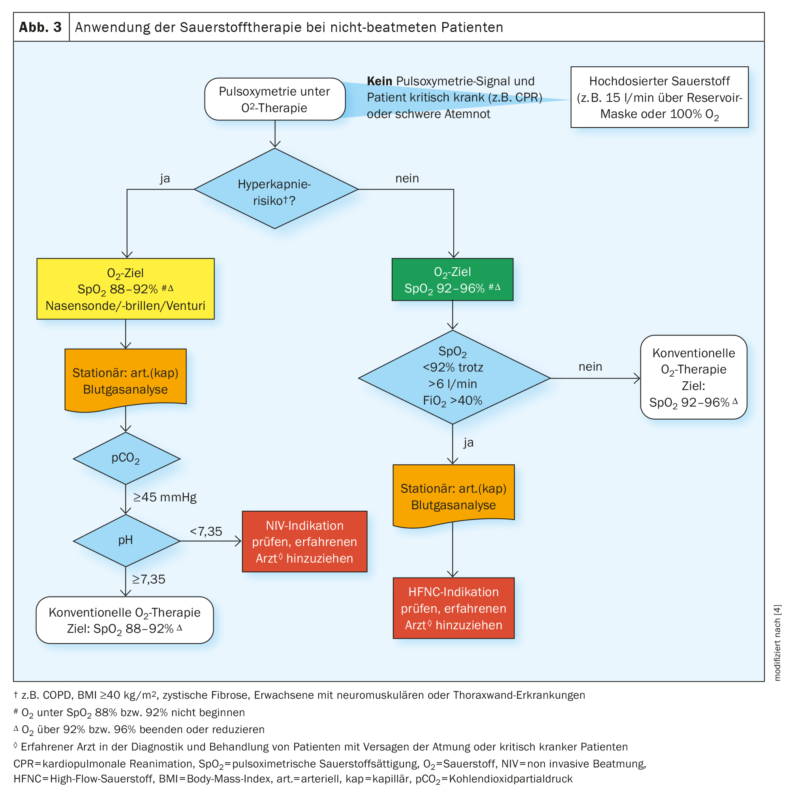

The target range of acute oxygen therapy for nonventilated patients without risk of hypercapnia should be between 92% and 96% for pulsoximetric saturation (Figs. 2 and 3). In case of an oxygen saturation below 92%, the initiation or increase of oxygen therapy is reasonable for patients without risk of hypercapnia. Above a saturation of 96%, discontinuation or reduction of oxygen therapy is indicated in these patients. The above target oxygen saturation values apply at rest. In acutely ill patients, values below the target range can be tolerated for a short time during exertion, coughing, if oxygen saturation returns to the target range rapidly (usually within less than 1 minute) after the event. For all patients on oxygen therapy, oxygen cards are useful for marking the SpO2 target range at the bedside.

Oxygen therapy for acutely ill, nonventilated patients at risk of hypercapnia (e.g., COPD) should be delivered with a target pulsoximetric saturation of 88-92%. Oxygen therapy should not be administered or reduced in this situation when saturation is above 92% and should not be started until saturation is below 88%.

In ventilated patients, an arterial oxygen saturation of 92% to 96% should be aimed for. In addition to arterial blood gas measurements, pulsoximetric measurement of oxygen saturation should be used to control oxygen delivery if agreement is acceptable (deviation up to 2%) and in the preclinical setting.

Patients who do not achieve an SpO2 of 92% despite flow rates greater than 6 liters of oxygen per minute should be immediately evaluated by a physician experienced in the diagnosis and treatment of patients with acute respiratory failure or critically ill patients.

Practical tip

In markedly hypercapnic and hypoxemic COPD patients with exacerbation, NIV is an important treatment option in acute therapy. In cardiac pulmonary edema with severe hypoxemia (FiO2 >0.4 or >6 l/min) under conventional oxygen therapy, NIV, CPAP, and HFNC are reasonable therapeutic alternatives. HFNC does not appear to be inferior to NIV in moderate hypercapnia.

Oxygen therapy for special patient groups

Carbon monoxide: In the event of carbon monoxide poisoning, 100% oxygen administration or ventilation with 100% O2 should be given immediately and for up to 6 hours, regardless of oxygen saturation (SpO2 ). In cases of severe carbon monoxide poisoning (e.g., with persistent impaired consciousness), hyperbaric oxygen therapy may be administered. Blood gas analysis is useful for assessing carbon monoxide poisoning and determining carbon monoxide bound to hemoglobin (CO-Hb). For this purpose, it is irrelevant whether this blood sample is venous, arterial or capillary. In carbon monoxide poisoning, immediate treatment with high-dose oxygen is useful for up to 6 hours, regardless of oxygen saturation. 80 Back to Table of Contents high-dose O2 therapy can also be delivered via NIV/CPAP, masks, or HFNC, not just the tube. With the exception of carbon monoxide poisoning, the usual target ranges of oxygen saturation (92 to 96% or 88 to 92% for hypercapnia risk) are reasonable for other poisonings with oxygen administration [3].

Prehospital: In the prehospital setting, oxygen should be administered with a target SpO2 range of 92 to 96% (or 88 to 92% in patients at risk of hypercapnia). Only if an O2 saturation cannot be reliably derived by pulsoximetry outside the hospital and the patient is in a critical condition (e.g., during resuscitation) should a high dose of oxygen (100% or 15 l/min) be administered.

If the signal from the SpO2 measurement is not reliable or not available, administer oxygen as if no pulse oximeter were available. With the exception of critical situations (e.g., during resuscitation), pulse oximetry is useful for assessment before administering oxygen, even in the prehospital setting. Medication nebulization with oxygen as a propellant in the prehospital setting should be avoided or timed in patients at risk for hypercapnia (K3). It is recommended that the following O2 delivery devices be maintained in the prehospital environment: O2 reservoir mask (for high concentration oxygen therapy); nasal cannulae, venturi masks, and O2 delivery systems for patients undergoing tracheostomy or laryngectomy, if applicable. A portable pulse oximeter for hypoxemia assessment and initial evaluation is essential in the prehospital setting, and a portable oxygen source is a useful part of the emergency equipment for critically ill patients or those in respiratory distress. In the prehospital setting, the ability to perform blood gas analyses is usually lacking; therefore, clinical recognition of patients at risk for hypercapnia is important.

Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation: The highest possible oxygen flow should be used during cardiopulmonary resuscitation. When spontaneous circulation resumes and oxygen saturation can be reliably monitored, a target saturation range of 92 to 96% should be aimed for.

A FiO2 of 1.0 should be used for ventilation during cardiopulmonary resuscitation.

Infectious patients: Oxygen treatment of adult patients with infectious diseases transmissible by aerosols (e.g., SARS-CoV-2) should follow the same principles and target ranges as for other patients with hypoxemia.

Cluster Headache: In patients with cluster headache, oxygen should be administered at a flow rate of at least 12 L/min for at least 15 minutes via a reservoir mask.

Sedation procedures with spontaneous breathing: In all procedures with sedation with the aim of maintaining spontaneous breathing, oxygen saturation should be continuously monitored pulsoximetrically before and during the procedure and in the recovery phase. In all procedures with sedation and the goal of preserved spontaneous breathing, if hypoxemia occurs (SpO2 <92% or 88% if at risk of hypercapnic respiratory failure), the presence of hypoventilation should be assessed and oxygen should be administered as part of a multimodal approach.

Practical tip

To detect frequent hypoxemia, continuous pulsoximetric monitoring is useful for all procedures with sedation. Hypoxemia under sedation is often caused by hypoventilation. Oxygen therapy for procedures with sedation has the same target ranges (SpO2 92 to 96% or 88 to 92% for patients at risk of hypercapnia) as for other conditions. Oxygen administration alone is often insufficiently effective in hypoxemia under sedation, and additional measures to correct hypoventilation are helpful.

High-flow oxygen therapy: In hospitalized patients with acute hypoxic respiratory failure without hypercapnia, oxygen therapy via high-flow oxygen should be initiated at 6 L O2/min via nasal cannula/mask and an oxygen saturation of <92%. Patients on high-flow oxygen therapy should be reevaluated closely and discontinuation criteria of HFNC should be established.

Summary

Oxygen is a medicinal product and should be prescribed by a physician only when indicated. Oxygen therapy must be documented in writing, monitored regularly, and reevaluated. Target oxygen saturation ranges depend on the risk of hypercapnia and the status of ventilation. More than a quarter of acute inpatients with hypoxemia have concomitant hypercapnia on blood gas analysis. The oxygen target range must be established for each acutely ill patient. For spontaneously breathing patients without risk of hypercanopy, the target range is SpO2 92 to 96% (peripherally measured saturation). For patients at risk of hypercapnia, the target SpO2 range is 88 to 92%. For ventilated patients, an arterial oxygen saturation between 92 and 96% is recommended. With a few exceptions (CO poisoning, resuscitative measures, cluster headache), the target ranges apply to all adult patients receiving oxygen therapy for acute hypoxemia and do not differ between individual diagnoses.

The new S3 guideline “Oxygen therapy in acute hypoxemia in adults” is the first German-language guideline on this topic. The guideline provides an overview of existing oxygen delivery systems and includes recommendations for selection based on patient safety and comfort. High-flow oxygen is suggested for patients who require more than 6 L of O2 per minute to reach target range. Patients on high-flow oxygen must then be monitored continuously.

No humidification is necessary for short-term and low-dose oxygen therapy. When discontinuing oxygen therapy, the risk of hypercapnia plays a role because of possible rebound hypoxemia. Reevaluation within a few weeks of discharge is recommended for patients who cannot be weaned from oxygen during inpatient treatment and who are prescribed O2 for home use. In this case, it must be checked whether the indication for long-term oxygen therapy persists.

Take-Home Messages

- Oxygen should be prescribed by a physician for each inpatient, specifying a target range of oxygen saturation.

- There should be written documentation of oxygen therapy.

- For stable patients and without risk factors, routine determination of blood gases should not be performed.

- The target range of acute oxygen therapy for nonventilated patients without risk of hypercapnia should be a pulsoximetric saturation of

between 92% and 96%. - In patients at risk of hypercapnia, a lower target range of

88-92% of oxygen saturation under O2 therapy medically reasonable.

Literature:

- Holmberg MJ, Nicholson T, Nolan JP, et al: Oxygenation and ventilation targets after cardiac arrest: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Resuscitation 2020; 152: 107-115.

- Rudolf M, Turner JA, Harrison BD, et al: Changes in arterial blood gases during and after a period of oxygen breathing in patients with chronic hypercapnic respiratory failure and in patients with asthma. Clin Sci (Lond) 1979; 57(5): 389-396.

- Joean O, Klooster MPV, Kayser MZ, et al: A cross-sectional study in three German hospitals regarding oxygen therapy characteristics. J Pneumology 2022; 76(10): 697-704.

- Gottlieb J, Capetian P, Fühner T, et al: S3 guideline: oxygen in acute therapy in adults. AWMF registry number 020-021; www.awmf.org/uploads/tx_szleitlinien/020-021l_S3_Sauerstoff-in-der-Akuttherapie-beim-Erwachsenen_2021-06.pdf (last accessed 07/12/2023).

- Cranston JM, Crockett A, Currow D: Oxygen therapy for dyspnea in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2008; 3: CD004769.

- Physicians RCo. National Early Warning Score (NEWS) 2: Standardising the assessment of acute-illness severity in the NHS. Updates report of a working party: RCP, London; 2017.

- Guidelines for organ transplantation according to. § Section 16 TPG: German Medical Association; 2017 (Available from: www.bundesaerztekammer.de/fileadmin/user_upload/downloads/pdf-Ordner/RL/RiliOrgaWlOvLungeTx-ab20171107.pdf; last accessed: 12.07.2023).

- O’Reilly Nugent A, Kelly PT, Stanton J, et al: Measurement of oxygen concentration delivered via nasal cannulae by tracheal sampling. Respirology 2014; 19(4): 538-543.

HAUSARZT PRAXIS 2023; 18(8): 7-13