When pain becomes a disease in its own right and no longer serves as a warning function of the body, it is referred to as chronic pain syndrome. Often, other symptoms such as sleep disturbances, lack of appetite or depressed mood are added. The disease burden is correspondingly high. How can those affected be helped effectively and quickly?

One of the most difficult indications – pain. They may occur diffusely throughout the body, specifically affect one area, recur in waves, or stop abruptly. The variants are many. As a rule, the sensory and emotional experiences that are perceived as unpleasant are a warning function of the body. It alerts to actual or impending tissue damage and represents a life-sustaining biological response to damaging agents. Pain can be experienced as burning, stabbing, piercing, or tearing. However, if they occur and persist independently of an acute event, they have lost their delusional function. Then they are usually no longer a symptom of the disease, but a disease in their own right.

Chronic pain has a memory

Pain is considered chronic if it persists beyond an understandable cause and lasts longer than three or six months. In total, about 1.5 million people in Switzerland are affected – 39% of them are always in pain, 35% daily, 26% several times a week. On average, sufferers have been battling chronic pain for 7.7 years, one in four for more than 20 years.

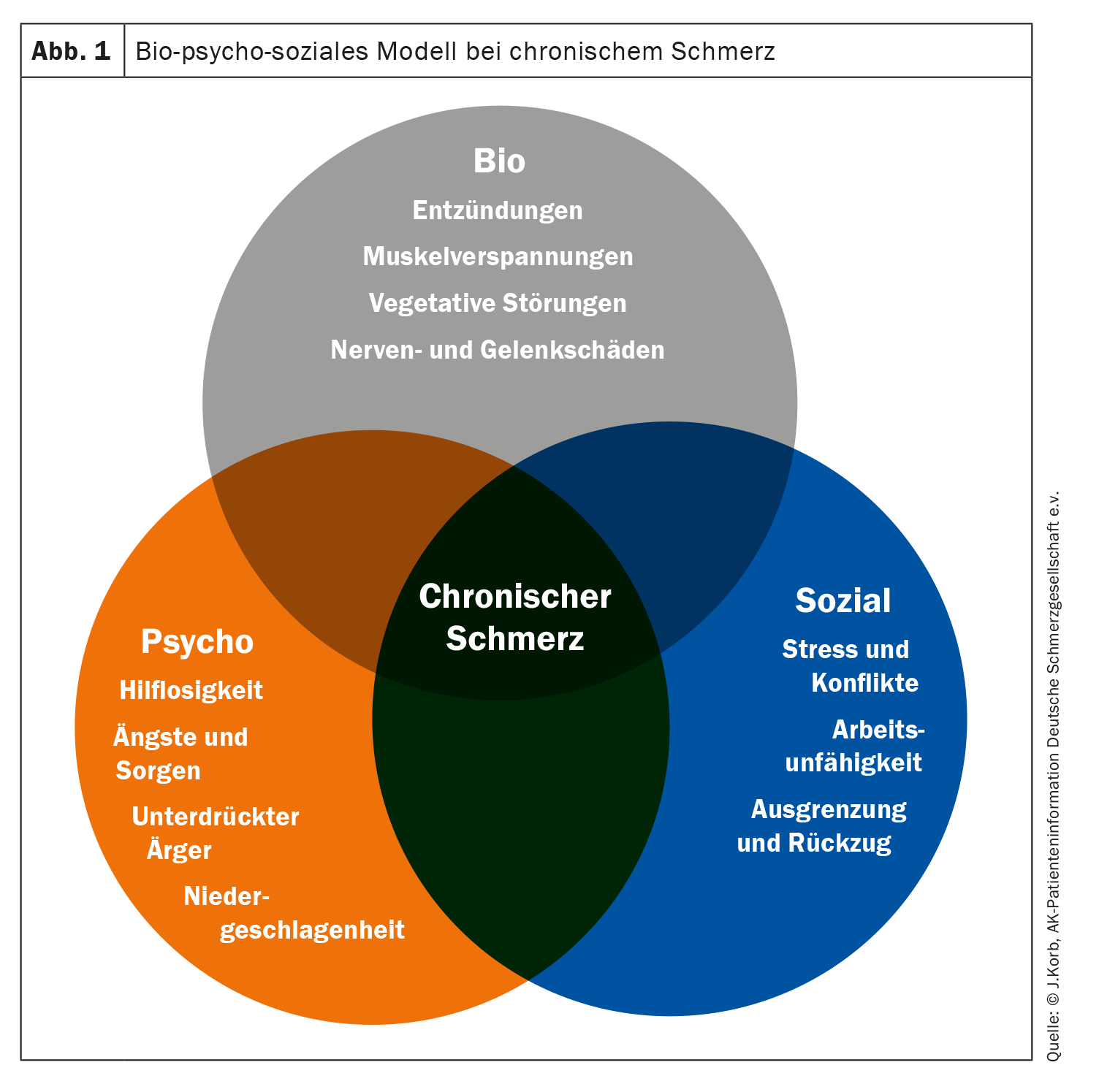

The causes are usually acute injuries, diseases or incorrect posture. These include, for example, wear and tear of the musculoskeletal system, vascular diseases, neuropathic pain or tumor pain. In primary chronic pain disorder, the symptoms occur periodically, as in migraine. In addition, however, acute pain may persist. Then the pain threshold was lowered to such an extent that even external stimuli that are actually harmless are perceived as painful. In some patients, pain fibers are activated even when there is no stimulus at all. This pain memory is dependent on somatic, psychological and social factors (Fig. 1).

The experience of being constantly exposed to pain without being able to control it is extremely stressful for patients psychologically. There may be a loss of zest for life, stress or even depression. Another big problem is that people who feel pain in certain situations avoid those situations. But a protective posture or reduced movement leads to a veritable vicious circle and to even greater pain. Patients also gradually fall into social isolation due to depressed mood and inactivity. Over time, many of those affected are even threatened with the loss of their job or early retirement.

Complex phenomenon, multimodal therapy in an interdisciplinary team

Based on the bio-psycho-social model, treatment approaches have also changed. There has been a shift from more symptomatic pain management with the goal of freedom from pain to comprehensive therapy of the physical, psychological, and social abilities limited by pain. The goal is, among other things, to increase fitness, load capacity, coordination and body awareness. In addition, patients should learn to better control their personal stress limits. In order to effectively counter these complex processes, comprehensive and modern therapy management is always multimodal – ideally in an interdisciplinary team. It usually consists of five pillars: medicinal, physiotherapeutic, psychotherapeutic, social and invasive.

It is important for drug intervention to be on a fixed schedule, with individualized dosing, anticipation of pain, controlled dose adjustment, and active side effect management. The anticipation of pain includes the next administration of medication before the pain recurs. The aim of these measures is to achieve the greatest possible continuous pain relief or, ideally, freedom from pain.

Medicinal pain therapy is structured in three stages according to the pain scheme of the World Health Organization (WHO):

- Stage 1: Non-opioid analgesics (non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs).

- Stage 2: low-potency opioid analgesics + non-opioid analgesics.

- Stage 3: high-potency opioid analgesics + non-opioid analgesics.

In pain patients without tumors, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) are among the most commonly used medications. Especially for mild to moderate pain, they show a good effect. However, in elderly and/or multimorbid patients and those on co-medication, special attention should be paid to good gastrointestinal, renal, and cardiovascular tolerability in addition to rapid onset and long duration of action. In addition, there should be no significant effect on platelet aggregation. The only indications for temporary therapy with opioids are diabetic nerve damage, after shingles, osteoarthritis, and chronic back pain. Opioid analgesics, however, are not first-line agents for the long-term management of chronic nontumor-related pain.

Further reading:

- www.schmerzgesellschaft.de/patienteninformationen/herausforderung-schmerz (last accessed 08.10.2023)

- www.usz.ch/krankheit/schmerzen-akuter-und-chronischer-schmerz (last accessed 08.10.2023)

- www.arztcme.de/elearning/therapie-chronischer-schmerzen-schwerpunkt-opioide—unter-besonderer-berucksichtigung-des-einsatzes-von-co-analgetika-und-antidepressiva/lernmodul/einleitung (last accessed 08.10.2023)

- www.ai-online.info/abstracts/pdf/dacAbstracts/2012/

2012-18-RC182.2.pdf (last accessed 08.10.2023) - https://cme.medlearning.de/arz/schmerzen_rez/pdf/cme.pdf (last accessed 08.10.2023)

- www.aerzteblatt.de/archiv/45427/Chronischer-Schmerz-Nur-interdisziplinaer-behandelbar (last accessed 08.10.2023).

InFo NEUROLOGY & PSYCHIATRY 2023; 21(5): 34-35.