As in adults, psoriasis is often associated with comorbidities in children and adolescents. The level of suffering is often high and psychosocial development can be affected. This makes a sustainable treatment strategy all the more important. A well-established, manageable range of active ingredients has been available for years for topical therapy. And in the field of systemic therapy, there have fortunately been a number of extensions to the indications for biologics in recent years.

In around a third of cases, psoriasis manifests itself in childhood and adolescence. The diagnosis can be made clinically in most cases. Plaque psoriasis is by far the most common (around 70%), with the foci often being smaller, less infiltrated and less scaly than in adults [1–3]. Although psoriasis in childhood and adolescence is less common than in adults, with a cumulative prevalence of 0.71%, there is a high demand for care in view of the chronicity and the often significant reduction in the quality of life of those affected and their environment [1]. Pract. med. Nataliia Zhovta, Assistant Physician and Research Associate, Dermatology, Children’s Hospital Zurich, gave an up-to-date overview of the management of psoriasis in pediatric patients with reference to empirical values, as well as the German s2k guideline published in 2022 and the US guidelines published in 2020 [1,4,5].

Common localizations and psoriasis subtypes

The hairy scalp is often affected first in pediatric psoriasis patients, the speaker reported [4]. Typical symptoms are thick, adherent, whitish scales on circumscribed redness and an excess of 1-2 cm beyond the hairline [1]. In up to 60% of children with psoriasis, the capillitum and face are affected; palmoplantar psoriasis affects around 50% of children and adolescents with psoriasis [5,6,8] and nail changes are found in around a third of this patient population [1,9]. As in adults, nail psoriasis is considered a predictor of psoriatic arthritis [9]. After plaque psoriasis, guttate psoriasis is the second most common subtype in pediatric psoriasis patients [4]. In the acute stage, monomorphic, bright red, scaly papules and small, round-oval plaques less than 1 cm in size in the region of the trunk, proximal extremities and, less frequently, the face are typical [2,3]. Pustular forms of psoriasis** are similarly rare in children (1.0-5.4%) as in adults [1]. The association of psoriasis and joint involvement in minors is known as juvenile psoriatic arthritis and occurs in up to 15-20% of patients with plaque psoriasis.

** Psoriasis pustulosa generalisata of the Zumbusch type, psoriasis pustulosa of the erythema anulare centrifugum type

Screening for comorbidities

A connection between psoriasis and obesity as well as other cardiovascular risk factors (arterial hypertension, hyperlipidemia, prediabetes) has also been proven in recent years by many studies in children and adolescents with psoriasis [7,14–16]. It was found that children with psoriasis are around three times more likely to be affected by (central) obesity than those without psoriasis [1]. Mood swings, depression and anxiety disorders are also relatively common in psoriasis patients, according to Pract. med. Zhovta [4]. Recommendations for comorbidity screening in children with psoriasis have included depression and anxiety disorders in the list of possible comorbidities [8]. Infections, especially streptococcal infections (tonsillitis, pharyngitis, streptogenic perianal dermatitis), are frequent trigger factors for the initial manifestation of psoriasis or flare-ups in children [10,11]. Psoriatic arthritis is slightly less common in children than in adult patients, explained Pract. med. Zhovta [4]. Last but not least, chronic inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) should also be considered in pediatric psoriasis patients, especially when it comes to the choice of systemic therapy, this has important implications.

Age-appropriate topical therapy: depending on severity and localization

An important pillar of treatment is basic therapy in the form of regular application of drug-free topical external agents. In early childhood, products with added fragrances should be avoided due to possible sensitization [12]. Humectants such as urea and glycerine, which support the skin barrier and balance the increased TEWL, are particularly recommended as they also have an antipruritogenic effect. It should be noted that urea can cause irritation in infants and small children.

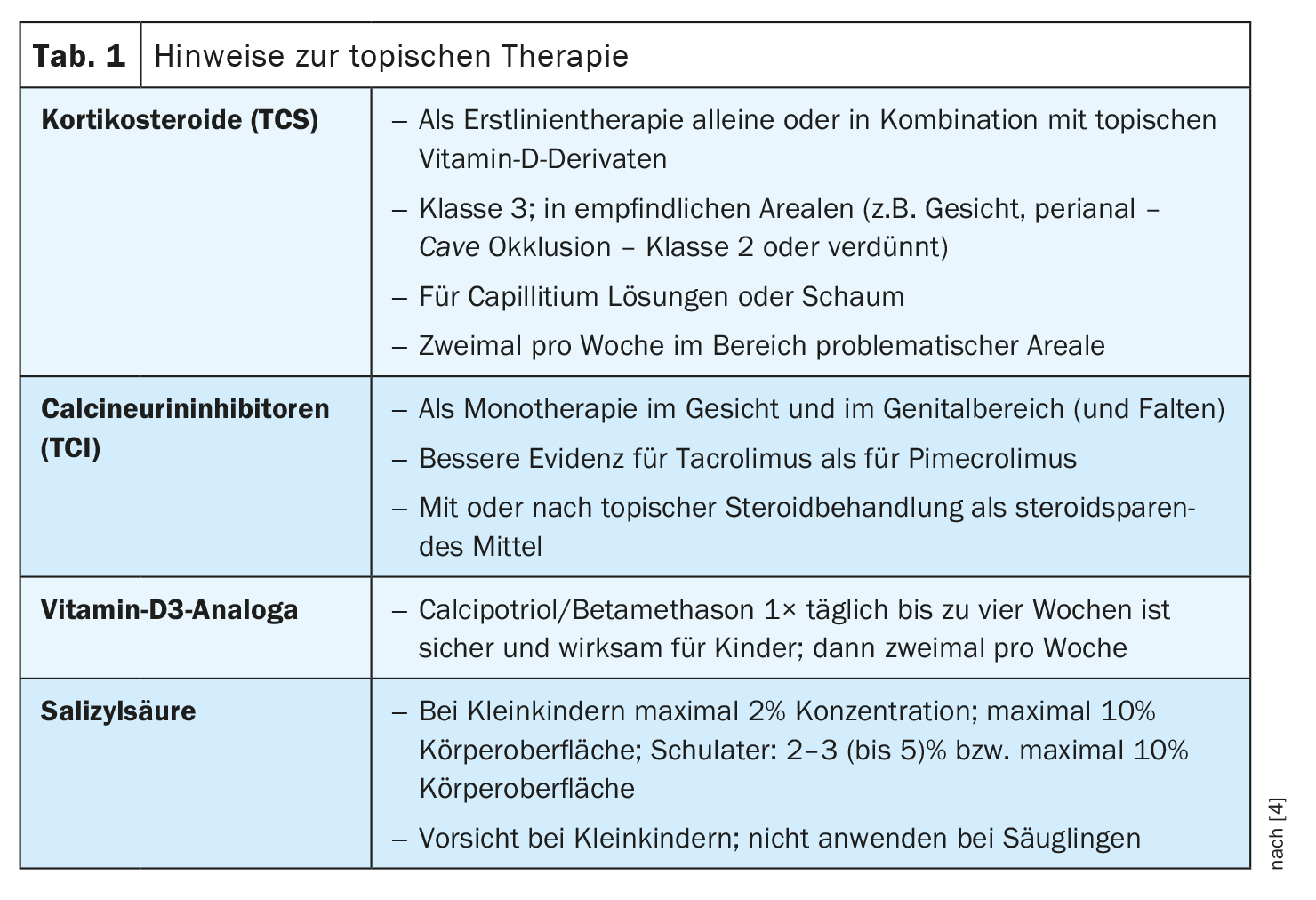

Anti-inflammatory topical therapy as first-line treatment of psoriasis is of particular importance in childhood and adolescence [1]. The majority of children can be successfully treated with topical preparations. Topical calcineurin inhibitors (TCI) can be used for psoriasis, but are only useful for certain problem areas due to their relatively weak efficacy. TCI inhibit T-cell activation and thus specifically intervene in inflammatory processes in the skin. Topical corticosteroids (TCS) are recommended as first-line therapy alone or in combination with topical vitamin D derivatives. Class 3 corticoids can be used in the short term; however, class 2 corticoids are preferable in sensitive areas (e.g. the face or perianal area). Topical vitamin A derivatives can be considered for the treatment of psoriasis if vitamin D derivatives and TCS have not been effective. Approved topical vitamin D derivatives (calcipotriol and tacalcitol) are recommended as primary therapy together with TCS and as follow-up therapy after TCS.

Topical preparations in the form of solutions or foam are often used for scalp infestations, which is better and more pleasant than ointments for various reasons, Pract explained. med. Zhovta [4]. She advises against using salicylic acid on infants.

Systemic therapy: Matching the choice of biologics to patient characteristics

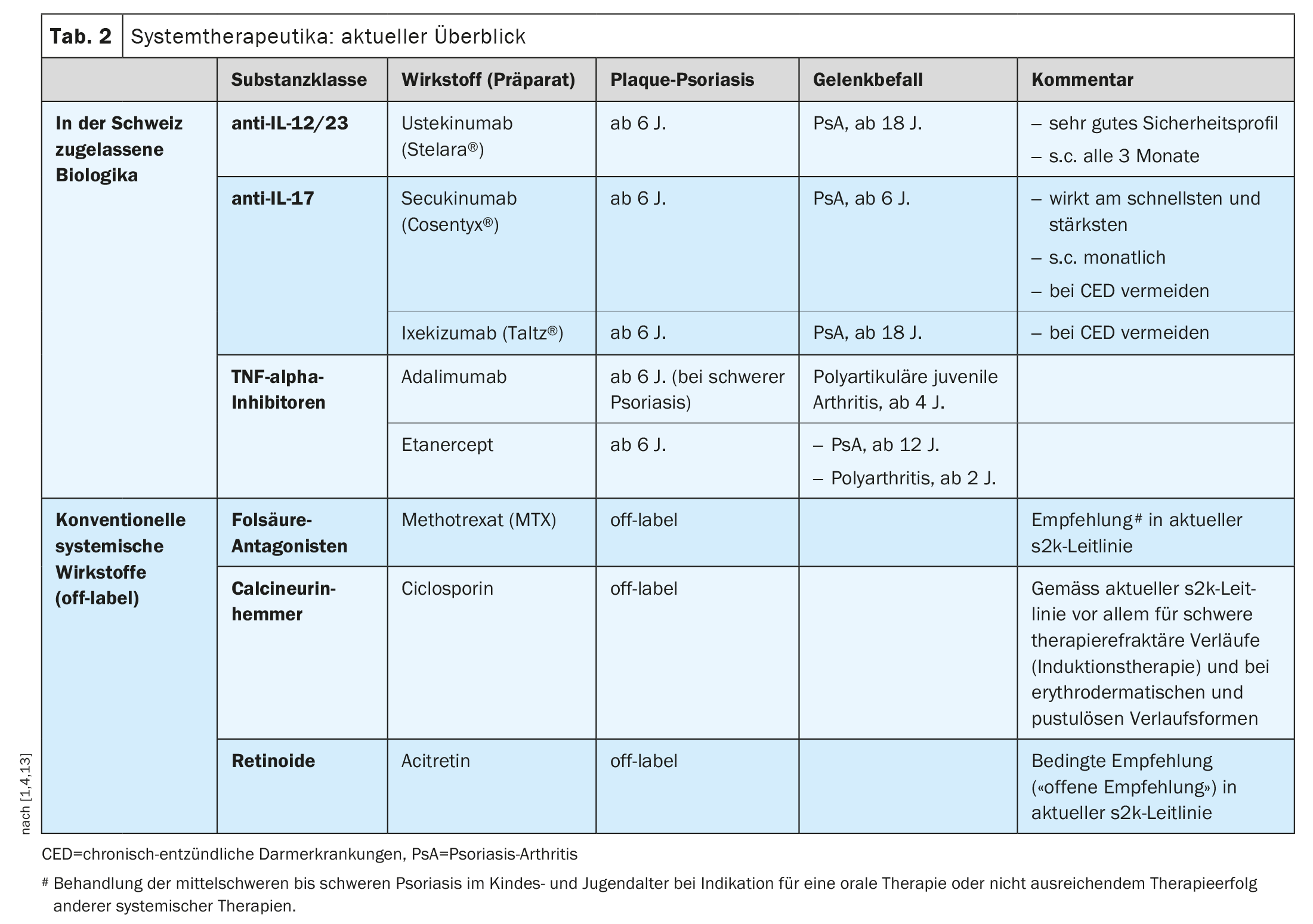

Nowadays, psoriasis is understood to be a T-cell-mediated autoimmune disease, i.e. the disease is triggered by an excessive immune reaction. This is the therapeutic target of immunosuppressive and immunomodulatory system therapeutics. The conventional systemic agents acitretin, ciclosporin, methotrexate (MTX) and fumaric acid esters have been used for psoriasis vulgaris in adults and children for many years, although these are off-label treatment options in this age group. However, several biologics are also officially approved for children and adolescents with psoriasis (Table 2) [13]. Nowadays, not only the TNF-α blockers etanercept and adalimumab are available, but with ustekinumab, secukinumab and ixekizumab, other highly effective monoclonal antibodies (mAb) have now been approved for this age group.

Ustekinumab is a mAb that binds specifically to the p40 subunit of IL-12 and IL-23, thereby preventing them from binding to the target receptor. Ustekinumab is approved in Switzerland for the treatment of moderate to severe plaque psoriasis from 6 years of age if the use of other systemic therapies or PUVA (combination of psoralen with UV-A) is not effective or if these therapies are not tolerated [13].

The two IL-17A inhibitors secukinumab and ixekizumab are also approved from the age of 6. Both monoclonal antibodies inhibit the interaction with the IL-17 receptor by binding to the pro-inflammatory cytokine interleukin 17A, thereby preventing keratinocyte activation and proliferation in psoriasis [13].

Other important treatment modalities

The current s2k guideline recommends the use of ultraviolet light [1]. The 311 nm wavelength has maximum biological activity while minimizing undesirable (skin-ageing) effects by filtering out the other UVB wavelength ranges. As a rule, therapy cycles of 20-30 sessions with 3-5 applications per week are required. According to the guideline, antibiotic treatment is indicated if tonsillitis or a perianal or vulvovaginal infection with evidence of streptococci is present, as is the case in particular with guttate psoriasis, which is more common in children than in adults. Psoriasis guttata can develop into psoriasis vulgaris, but it can also heal completely.

Congress: Zurich Children’s Skin Day

Literature:

- S2k Guideline Therapy of psoriasis in children and adolescents. AWMF Register 013 094 2021. https://register.awmf.org/assets/guidelines/013-094l_S2k_Therapie-der-Psoriasis-bei-Kindern-und-Jugendlichen_2022-04.pdf,(last retrieval 18.01.2024)

- Bronckers IM, et al: Psoriasis in Children and Adolescents: Diagnosis, Management and Comorbidities. Paediatric drugs 2015; 17: 373-384.

- Relvas M, Torres T: Pediatric Psoriasis. American journal of clinical dermatology 2017; 18: 797-811.

- “Psoriasis of childhood: How do we treat it today?”, Pract. med. Nataliia Zhovta, Zurich Children’s Skin Day, 01.12.2023.

- Menter A, et al: Joint American Academy of Dermatology-National Psoriasis Foundation guidelines of care for the management and treatment of psoriasis in pediatric patients. JAAD 2020; 82(1): 161-201.

- Hanafi B, et al: Groupe de Recherche sur le Psoriasis (GrPso) of the Société Française de Dermatologie (SFD), Groupe de Recherche de la Société Française de Dermatologie Pédiatrique (GR SFDP), and Società Italiana di Dermatologia Pediatrica (S.I.Der.P.). Effectiveness of biologic therapies in children with palmoplantar plaque psoriasis: An analysis of real-life data from the BiPe cohorts. Pediatr Dermatol 2023; 40(5): 835-840.

- Tollefson MM, et al: Association of Psoriasis With Comorbidity Development in Children With Psoriasis. JAMA Dermatol 2018; 154: 286-292.

- Osier E, et al: Pediatric Psoriasis Comorbidity Screening Guidelines. JAMA Dermatol 2017; 153(7): 698-704.

- Pourchot D, et al: Nail Psoriasis: A Systematic Evaluation in 313 Children with Psoriasis. Pediatric dermatology 2017; 34: 58-63.

- Horton DB, et al: Antibiotic Exposure, Infection, and the Development of Pediatric Psoriasis: A Nested Case-Control Study. JAMA dermatology 2016; 152: 191-199.

- Thorleifsdottir RH, et al: Throat Infections are Associated with Exacerbation in a Substantial Proportion of Patients with Chronic Plaque Psoriasis. Acta dermatovenereologica 2016; 96: 788-791.

- Lukas A, Wolf G, Folster-Holst R: [Special features of topical and systemic dermatologic therapy in children]. Journal of the German Dermatological Society 2006; 4: 658-678; quiz 79-80.

- Swissmedic: Medicinal product information, www.swissmedicinfo.ch,(last accessed 18.01.2024).

- Mahe E, et al: Psoriasis and obesity in French children: a case-control, multicentre study. The British Journal of Dermatology 2015; 172: 1593-600.

- Skinner AC, et al: Cardiometabolic Risks and Severity of Obesity in Children and Young Adults. The New England Journal of Medicine 2015; 373: 1307-1317

- Tom WL, et al: Characterization of Lipoprotein Composition and Function in Pediatric Psoriasis Reveals a More Atherogenic Profile. The Journal of Investigative Dermatology 2016; 136: 67-73.

DERMATOLOGIE PRAXIS 2024; 34(1): 50-52 (published on 20.2.24, ahead of print)