The climate crisis is the greatest threat to human health. This statement, repeated by many national and international organizations, is of central importance when it comes to clarifying the role of healthcare in times of global climate crisis. The healthcare sector is not only called upon to warn of the consequences of the climate crisis (e.g. heat protection) and mitigate them (e.g. treatment of allergies), but is also called upon to reduce its contribution to the climate crisis.

You can take the CME test in our learning platform after recommended review of the materials. Please click on the following button:

The climate crisis is the greatest threat to human health.

This statement, repeated by many national and international organizations, is of central importance when it comes to clarifying the role of the healthcare sector in times of global climate crisis.

The healthcare sector is not only called upon to warn of the consequences of the climate crisis (e.g. heat protection) and to mitigate them (e.g. treatment of allergies), but is also called upon to reduce its contribution to the climate crisis.

In the European Union, the healthcare sector is responsible for an average of 4.7% ofCO2 emissions[1]. Within the healthcare sector, medical products, medical devices and medicines as well as associated supply chains and energy consumption account for the largest share at 71% [1]. Against this backdrop, the German Medical Association in 2021 called for the German healthcare system to become climate-neutral by 2030.

Emissions from inhalants

In order to implement this requirement, it is first necessary to analyze the footprint. In the outpatient sector, the prescription of medicines (alongside emissions from mobility, transportation and energy) is one of the main contributors to the footprint, as a study of GP practices in western Switzerland has shown [2]. In the group of medicines, inhaled medicines used to treat chronic respiratory diseases such as bronchial asthma and COPD have the highestcarbon footprint. Metered-dose inhalers (MDIs) play the decisive role here [3].

The use of the chlorofluorocarbon (CFC) type propellants previously used exclusively in the formulation of DA was banned in 1991 by the CFC-Halon Prohibition Ordinance and pharmaceutical manufacturers were required to gradually replace them with hydrofluoroalkanes (fluranes) as propellants. Although these do not damage the atmospheric ozone layer, they are powerful greenhouse gases. As a result, DA have a much higher global warming potential (GWP) for the atmosphere compared to DPI. In relation toCO2 with a GWP of 1, the norflurane (HFA-134a) used in most DPIs has a GWP of 1530, while the apaflurane (HFA-227ea) also used has a GWP of 3600 [4]. In total, this means that in the UK, DA is responsible for 3.5% of the GWP of greenhouse gas emissions from the entire UK healthcare system [5]. At the same time, clinically equivalent alternatives are available in the form of powder inhalation systems (DPI), which leave a much smaller footprint due to their propellant-independent, active aerosol generation (10 to 40 times lowerCO2 footprint compared to propellant-free DA) [3].

The production, packaging and distribution of medicines also contribute to the overallCO2 footprint. In relation to the propellant used, these factors only play a minor role [3].

For historical and cultural reasons, the market shares of DPIs vary considerably from country to country, from 13% in Sweden to 88% in the USA [3,6]. According to data from the Zentralinstitut für die Kassenärztliche Versorgung (ZI), DPIs account for around 50% of all prescribed inhaled medicines in Germany [7]. A comparison with other countries such as Sweden, where DPIs are used much more frequently, makes it clear that there is considerable potential for reducing the use of climate-damaging propellants.

In 2019, DA emitted propellants with a totalCO2 equivalent of 430,000 tons in Germany. A research project calculated the possible effects of various scenarios for reducing these emissions. A mandatory switch of 80% of all DA to DPI by 2030 would reduce these emissions by 68%. If, on the other hand, 5% of DAs were converted to DPI each year, a reduction of 27% could still be achieved in the same period [8].

Against this background, the S1 guideline “Climate-conscious prescription of inhalants” was drawn up in 2022. Just one year later, it was upgraded to an S2k guideline under the joint leadership of the German Society for Pulmonology and Respiratory Medicine (DGP) and the participation of other specialist societies (pediatrics, internal medicine, pharmacy). The guideline is intended to provide concrete assistance in the prescription of inhaled drugs by summarizing existing evidence on the decision between DPI and DA and explicitly addressing the aspect of climate damage caused by propellants when choosing between DPI and DA.

Clinical care

In Switzerland, around 850,000 people are affected by bronchial asthma or COPD; in Germany, the figure is around 15 million. In 2022, a total of 1,456 million defined daily doses (DDD) of medication for the treatment of asthma and COPD were prescribed at the expense of statutory health insurance. The largest share (657.3 million DDD; 45.1%) was prescribed by general practitioners in private practice, a further 300.8 million DDD (20.7%) by internists working as general practitioners and a further 397.0 million DDD (27.3%) by pulmonologists [9].

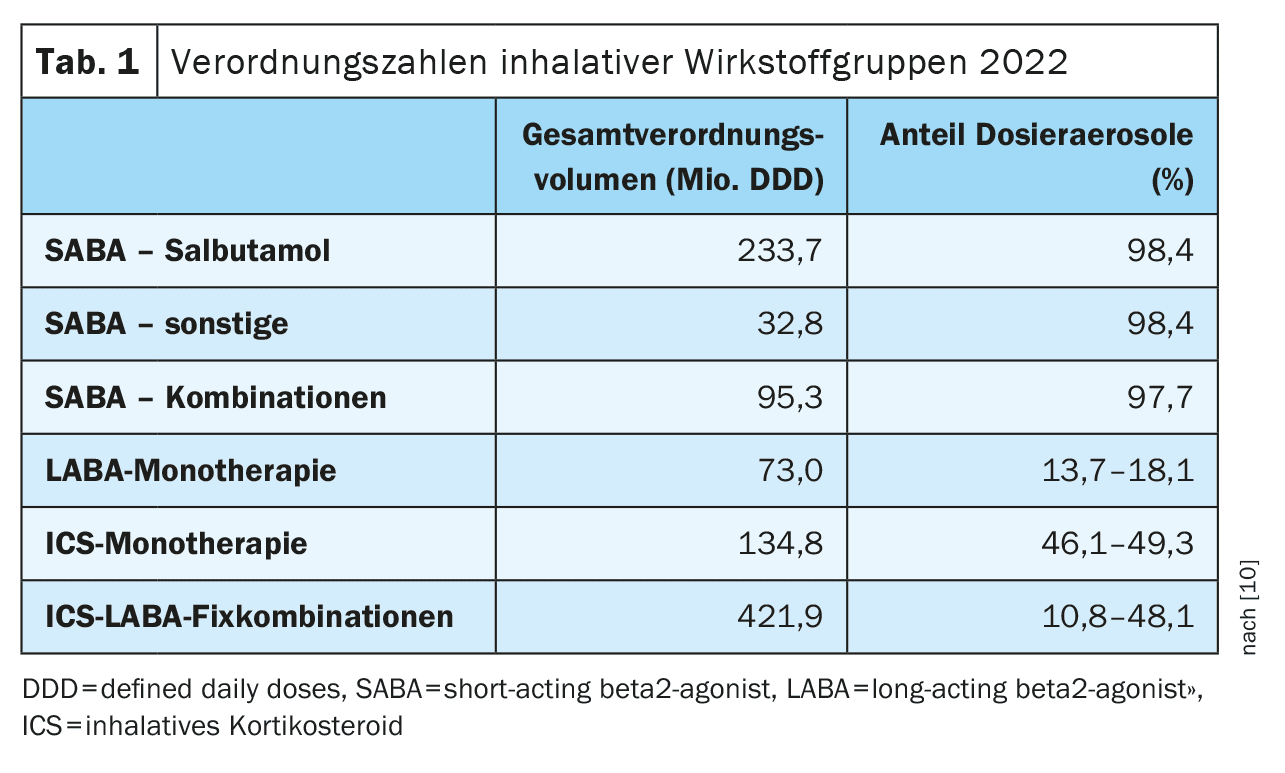

According to the prescription data [10], the proportion of DAs in the individual active ingredients differs significantly. While salbutamol as the lead substance of the short-acting beta-2-sympathomimetics (SABA) is prescribed almost exclusively as DA (98.4%), the proportion of DA in the long-acting beta-2-sympathomimetics (LABA) is less than 20% (13.7-18.1%) and in monotherapy with inhaled corticosteroids (ICS) between 46% and 49% (Table 1). The reason for the dominance of DA in SABA used exclusively as relievers is that in acute asthma a relevant limitation of inspiratory airflow is assumed, in which passive aerosol generation by propellant expansion works more reliably than with flow-dependent, active aerosol generation by DPI. There is no conclusive evidence for the general superiority of DA over DPI.

In addition to the high proportion of DAs for individual active ingredients, the national prescription figures also indicate a considerable misuse and overuse due to non-compliance with the guideline recommendations.

For example, the high use of short-acting drugs, which are prescribed almost exclusively as DAs, is striking in an international comparison.

According to a statement in the National Asthma Care Guideline, “a low need for short-acting beta-2 sympathomimetics (SABA) is an important goal and a criterion for the success of therapy”; this is operationalized in such a way that anti-inflammatory therapy is recommended for “more than twice-weekly use of SABA”.

In other words, asthma is considered well controlled if adults do not need to use SABA more than twice a week and children and adolescents do not need to use it at all [11].

Consistent implementation of the guideline recommendation in terms of therapy escalation through the implementation of long-term anti-inflammatory therapy could lead to a reduction in the unchanged high SABA requirement and thus the footprint.

Alternatively or additionally, a switch to a stronger prescription of salbutamol as DPI is also possible.

According to a review, the effect is also comparable when used in acute exacerbations [12] and could further reduce the prescription rate of DA.

In principle, international guidelines (“British guideline on the management of asthma”, Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network [SIGN] and British Thoracic Society [BTS]) already contain recommendations on climate-conscious prescribing and have also included this aspect in decision aids for patients [13].

The National Disease Management Guidelines (NVL Asthma/COPD) do not yet contain any corresponding recommendations.

There have also been no systematic studies in Germany to date on the effects of consistent advice and training on the climate-conscious prescription of inhalants for patients and prescribers.

Sociological studies indicate that the implementation of measures in such “niches” entails more complex changes that go far beyond the actual measure itself [14].

In terms of medical advice, climate-conscious prescribing of inhalants can potentially be an impetus for taking climate damage into account in other diagnostic or therapeutic decisions.

Estimation of the filling level

In addition to the footprint caused by the propellants contained, there are other arguments in favor of the primary use of DPI.

For example, patients can generally only estimate the filling level of the DA, as most preparations do not have an integrated counter.

This circumstance favors increased consumption (due to premature re-prescription) and increases the risk of inadequate treatment (due to the use of a largely empty DA with reduced drug release) [15,16].

In a prospective study with pediatric patients, there were serious misjudgements here because DAs that had already been emptied were considered usable.

In the end, however, these almost only released propellants [16].

A float test in a water bath is a very unreliable method for determining the filling level, weighing the cartridge is much more reliable, but just as impractical in everyday use due to a lack of published reference values [17].

DPI, on the other hand, usually contain a counter in the case of reservoir or blister systems or, in the case of capsule-based systems, enable simple residual quantity estimation.

This makes the application more resource-efficient and at the same time increases the safety of drug therapy.

Individual decision-making process

The aforementioned aspects of lower climate impact and more sustainable resource consumption through better control of the filling status speak in favor of the preferential use of a DPI. The following recommendations were derived from this in the S2k guideline:

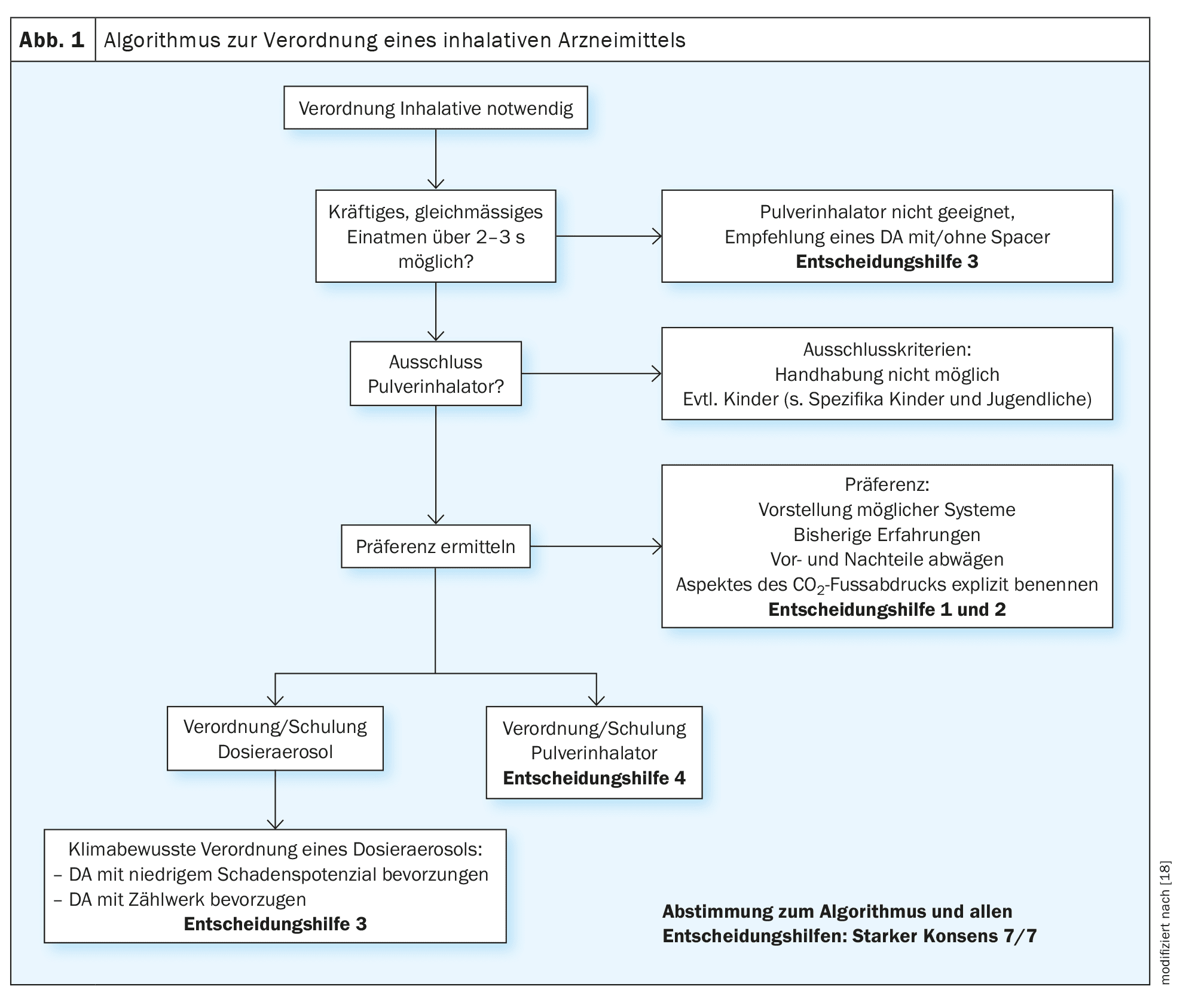

The decision for or against a DA is not only made when a new prescription is issued, but also regularly when the medication once prescribed is prescribed again. The guideline contains an algorithm (Fig. 1) that is intended to clarify the decision paths and thus support the prescribing process.

According to the NVL Asthma, the individual selection of inhalation devices should be based on the patient’s motor and cognitive abilities [11]. In addition to the skills and individual prerequisites (sufficiently deep inhalation, limitation of inspiratory airflow), individual preferences and coping with the respective device are also decisive, not least in geriatric patients. Qualified initial instruction (explanation, demonstration, practice under supervision) and monitoring are essential in order to check the patient-specific suitability of a jointly selected device.

The main advantages of DA are the lower demands on the inspiratory breath (generally suitable for patients with inspiratory flow limitation) and the possibility of combining it with an inhalation aid (pre-chamber, spacer). The latter can make it easier to coordinate the triggering of the spray burst and simultaneous slow inspiration. The use of an inhalation aid is therefore particularly recommended for infants and young children and for patients with coordination problems that cannot be corrected by training. From school age, DPI can also be considered for patients with coordination problems, provided the inspiratory airflow is sufficient. Coordination problems only play a very minor role here, as active aerosol generation only requires strong suction on the mouthpiece. In some guidelines, specific age specifications are made with regard to the use of certain devices. For example, the NVL Asthma recommends using a DA with spacer in children under five years of age [11]. However, as motor and cognitive skills can vary greatly in children, it is always advisable to focus on actual abilities. For both children and adults, the affected person must be able to demonstrably cope with the prescribed device.

Climate-conscious consulting

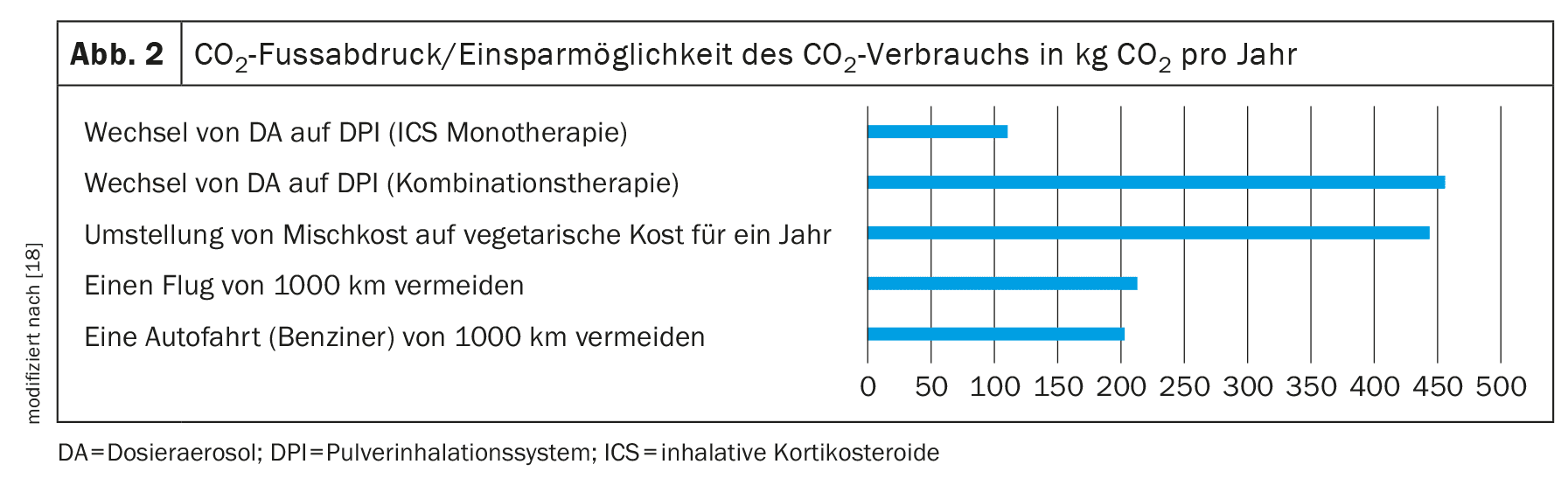

In addition, the guideline suggests explicitly mentioning the aspect of the CO2 footprint in this decision-making process. To support this consultation, decision-making aids have been created to illustrate the potential savings effect of switching from DA to DPI per year (Fig. 2).

The potential savings listed in the decision aid represent the maximum possible reductions in thecarbon footprint that can be achieved by switching to a therapy with DPI. Depending on the therapy used and the necessary dosage, the reduction in theCO2 footprint can also be lower. For example, replacing a monotherapy with an inhaled steroid leads to a saving of around 110 kgCO2 equivalent [19].

Waste disposal

Even after complete release of the declared number of individual doses, MDI cartridges are never completely empty, but still contain small residual quantities of the propellant or active ingredients. Empty metered dose inhalers therefore also formally belong to the category of problematic waste that requires regulated disposal. However, the disposal of pharmaceutical waste is regulated differently from state to state and there is no standardized concept. As residual waste is predominantly incinerated, medicines – with a few exceptions (e.g. cystostatics) – may be disposed of with household waste. A previously implemented take-back obligation for old medicines does not exist, nor do separate disposal routes for compressed gas cartridges. The disposal process and related recommendations are not usually a core topic of a guideline. Nevertheless, this topic was taken up in the guideline and addressed with a call for a disposal concept for compressed gas cartridges.

Implementation of the guideline

Various aspects are important for the implementation of the guideline. One basic requirement is appealing information material such as a short version of the guideline, information for patients and support services to enable the contents of the guideline to be implemented in practice. A GP colleague has developed an overview table containing all relevant active ingredients and their availability as a metered dose inhaler or powder inhaler. It also provides information on current prices and whether a counter is available.

Ideally, implementation at practice level could consist of checking whether it is possible to switch to a DPI when prescribing each repeat prescription. The fact that a change at practice level is possible was demonstrated in a pulmonology practice group. Within one year, the proportion of DPIs in the prescribed packs was increased from 49.2% to 77.8% [19].

Within the framework of discount agreements, medicines are often exchanged in pharmacies.

According to the Medicines Guideline, inhaled dosage forms are not included in the list of interchangeable medicines [20], meaning that the exchange of a DPI in favor of a DA or vice versa is not permitted in pharmacies.

In cases of doubt, the NVL Asthma recommends that the pharmacist should raise pharmaceutical concerns in these cases.

Alternatively, the exchange can also be avoided by ticking the “Aut-idem” box.

A planned practical test will be carried out to determine the acceptance and possible barriers to the implementation of the guideline in GP practices.

Take-Home-Messages

- In contrast to powder inhalers, metered dose inhalers contribute significantly to climate change due to the propellants they contain.

- For most patients, it is possible to switch from metered dose inhalers to powder inhalers.

- Both when prescribing inhalants and as part of the DMP asthma/COPD consultation, patients can be informed and their willingness to switch can be actively determined by the practice team.

Literature:

- Karliner J, Slotterback S, Boyd R, et al: Health cares climate footprint 2019. https://noharm-uscanada.org/ClimateFootprintReport. Last accessed: 5.01.2024.

- Nicolet J, Mueller Y, Paruta P, et al: What is the carbon footprint of primary care practices? A retrospective life-cycle analysis in Switzerland. Environ Health 2022; 21(1): 1-10.

- Janson C, Henderson R, Löfdahl M, et al: Carbon footprint impact of the choice of inhalers for asthma and COPD. Thorax 2020; 75(1): 82-84.

- Forster P, et al: The Earth’s energy budget, climate feedbacks, andclimate sensitivity. Climate change 2021: the physical science basis contribution of working group I to the sixth assessment report of the intergovernmental panel on climate change 2021; S923-1054.

- Environmental Audit Committee – House of Commons 2018 UK progress on reducing F-gas emissions. https://publications.parliament.uk/pa/cm201719/cmselect/cmenvaud/469/46905.htm#_idTextAnchor015. Last accessed: 21.01.2024.

- Pritchard JN: p>the climate is changing for metered-dose inhalers and action is needed. Drug Des Devel Ther 2020; 14: 3043-3055.

- Central Institute for Statutory Health Insurance Physician Care in Germany 2020. Prescription data for inhalants; www.zi.de.

- Pernigotti D, et al: Reducing carbon footprint of inhalers: analysis of climate and clinical implications ofdifferent scenarios in five European countries. BMJ Open Respir Res 2021; 8(1): e1071.

- Wissenschaftliches Institut der AOK: Der GKV-Arzneimittelmarkt: Klassifikation, Methodik und Ergebnisse 2023. www.wido.de/fileadmin/Dateien/Dokumente/Forschung_Projekte/Arzneimittel/wido_arz_gkv_arzneimittelmarkt_klassifikation_methodik_

ergebnisse_2023.pdf. Last accessed: 5.01.2024. - Ludwig WD, Mühlbauer B, Seifert R: Drug Prescription Report 2022. https://link.springer.com/10.1007/978-3-662-66303-5. Last accessed: 5.03.2023.

- German Medical Association, National Association of Statutory Health Insurance Physicians, Association of the Scientific Medical Societies: National Care Guideline Asthma 2020. www.leitlinien.de/themen/asthma. Last accessed: 12.01.2023 (long version, 4th edition).

- Selroos O: Dry-powder inhalers in acute asthma. Ther Deliv 2014; 5(1): 69-81.

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence: Asthma inhalers and climate change 2022. www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng80/resources/inhalers-for-asthma-patientdecision-aid-pdf-6727144573. Last accessed: 5.01.2024.

- Geels FW, Schot J: Typology of sociotechnical transition pathways. Res Policy 2007; 36(3): 399-417.

- Hasegawa K, Brenner BE, Clark S, Camargo CA: Emergency department visits for acute asthma by adults who ran out of their inhaled medications. Allergy Asthma Proc 2014; 35(3): 42-50.

- Fullwood I, et al: Do you know when the inhaler is empty? Arch Dis Child 2022; 107: 902-905.

- Rubin BK, Durotoye L: How do patients determine that their metered-dose inhaler is empty? Chest 2004; 126(4): 1134-1137.

- Schmiemann G, Dörks M, Grah C: S2k guideline on climate-conscious prescription of inhalants. www.awmf.org/service/awmf-aktuell/klimabewusste-verordnung-von-inhalativa. Last accessed: 12.01.2024.

- Bickhardt J, Czupalla C, Bader U: Reduction of climate-damaging greenhouse gases through selection of inhalers in the treatment of patients with asthma and COPD. Pneumology 2022; 76(5): 321-329.

- Federal Joint Committee Annex VII to Section M of the Drug Guideline – Regulations on the interchangeability of medicinal products (aut idem). www.g-ba.de/downloads/83-691-813/AM-RL-VII_Aut-idem_2023-08-15.pdf. Last accessed: 12.01.2024.

| Funding: Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL. Open Access. This article is published under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, duplication, adaptation, distribution, and reproduction in any medium or format, provided you give proper credit to the original author(s) and source, include a link to the Creative Commons License, and indicate if changes have been made. The images and other third-party material contained in this article are also subject to the Creative Commons License mentioned above, unless otherwise indicated in the image legend. If the material in question is not subject to the aforementioned Creative Commons license and the action in question is not permitted by law, the consent of the respective rights holder must be obtained for the further use of the material listed above. For further details on the license, please refer to the license information at http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/deed.de. The CME questions are a supplement from the publisher. |

FAMILY PHYSICIAN PRACTICE 2024; 19(8): 6-10