An updated version of the s2k guideline “Diagnosis, prevention and treatment of hand eczema” was published in 2023. It is proposed to classify hand eczema/chronic hand eczema from an etiological point of view into allergic or irritant contact dermatitis, atopic hand eczema and protein contact dermatitis, whereby mixed forms are often present. Topical, physical and systemic therapy options are currently available for treatment. In the case of allergic and irritant eczema, it is important to identify trigger factors and take appropriate skin protection measures.

| Text is mainly based on the s2k guideline “Diagnosis, prevention and treatment of hand eczema” published in 2023 (AWMF register no.: 013-053, as of: 23/02/2023) and on the current European ESCD guideline by Thyssen et al. 2022. |

Hand eczema (HE) is a common inflammatory skin disease with a 1-year prevalence of 9.7% in the adult general population [1]. There are acute or chronic forms of HE, with different degrees of severity and subtypes [2]. In 2023, an updated version of the s2k guideline “Diagnosis, prevention and treatment of hand eczema” was published, based on the European ESCD guideline [2,3]. According to the definition, chronic hand eczema (CHE) is present if the eczema localized on the hands occurs for more than three months or at least twice a year [2]. Chronic forms are common, usually due to a multifactorial etiology. The socio-medical effects associated with chronicity due to occupational, social and psychological stress are considerable and lead to a reduction in health-related quality of life (HR QOL) [4,5]. CHE are among the most common clinical pictures in dermatological and occupational health settings [6]. Topical, physical and systemic therapy options are currently available for the treatment of hand eczema [2]. However, there is an unmet need for well-tolerated, long-term treatment alternatives, particularly for moderate to severe CHE. Various research projects have been launched in this context.

You can take the CME test in our learning platform after recommended review of the materials. Please click on the following button:

Epidemiology and disease burden

In a recent population-based Danish study, the 1-year prevalence of hand eczema in the total population was 13.3%, with 35.1% of those affected having a moderate to severe manifestation and 82.6% fulfilling the criteria for CHE [7]. The extent of loss of quality of life correlates positively with the severity and duration of the disease [7]. Cracked skin, swelling, blisters and inflammation with weeping, crusty lesions are detrimental to everyday life. Studies have shown that hand eczema has the same negative impact on health-related quality of life (HRQoL) as psoriasis or asthma [8,9]. These negative effects are more pronounced for women than for men and women [10,11]. In a multicenter study, it was also observed that hand eczema sufferers were more likely to experience higher levels of stress, depression, anxiety and suicidal thoughts compared to the general population [10]. The ability to work and daily activities can be impaired and it is not uncommon for sleep disorders to develop, which further increases the level of suffering [9,12].

Etiology, morphology and classification

The classification of hand eczema is generally based on the underlying etiology rather than morphology, disease progression and anatomical localization, although the clinical picture is often used as an additional feature, especially in cases of unclear etiology [2]. The current guideline proposes the following etiologic classification according to subtypes: [2,3]

- Irritant contact dermatitis

- atopic hand eczema

- allergic contact dermatitis

- Protein contact dermatitis (with and without contact urticaria).

The most common forms are irritant and atopic hand eczema, followed by allergic contact dermatitis; protein contact dermatitis is rather rare. Mixed forms are particularly common in CHE, for example irritant contact dermatitis often occurs together with allergic contact dermatitis or atopic hand eczema [2,13].

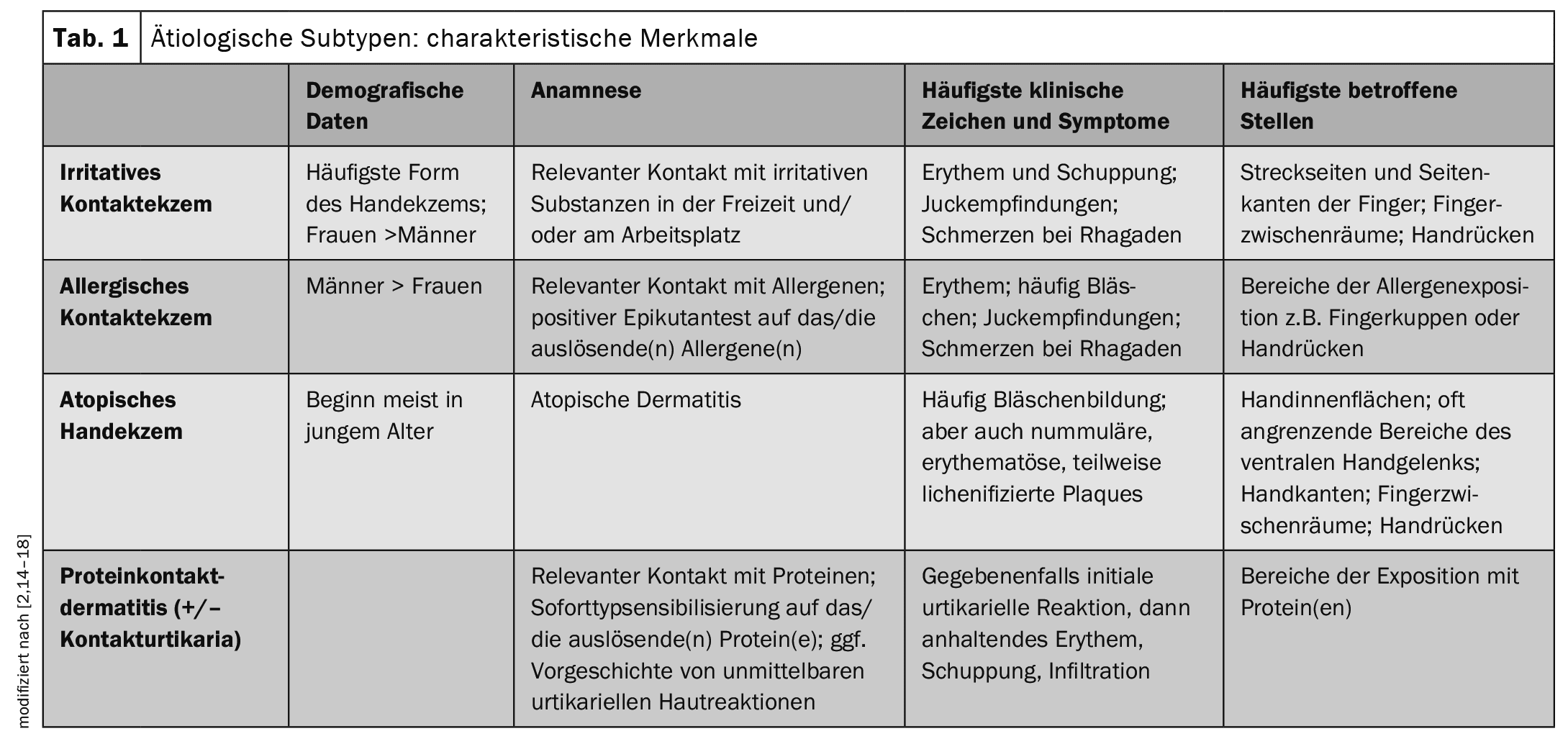

Table 1 provides an overview of the characteristic features of etiological subtypes [2,14–18].

A classification according to morphological changes distinguishes the following manifestations:

- nummular hand eczema

- vesicular hand eczema

- Hyperkeratotic hand eczema

- Eczema of the fingertips (pulpitis).

Acute efflorescences manifest as erythema, oedema, oozing, crusts, papules and vesicles/bullae. Chronic efflorescences include lichenification, scaling, hyperkeratosis, fissures and rhagades [2,3]. All subtypes are accompanied by pruritus, other common symptoms are pain, burning and stinging of the skin. It should be borne in mind that hand eczema is often polymorphic. For example, patients with CHE often present with a combination of erythema, scaling, lichenification, oedema, hyperkeratosis, vesicles and fissures in the area of the hands and wrists [3].

Histologic changes depend on the stage of the disease and include intercellular edema, spongiosis, acanthosis and parakeratosis in the epidermis, while perivascular infiltrates of lymphocytes occur in the upper dermis, which in turn may migrate into the epidermis.

Medical history and clinical examination

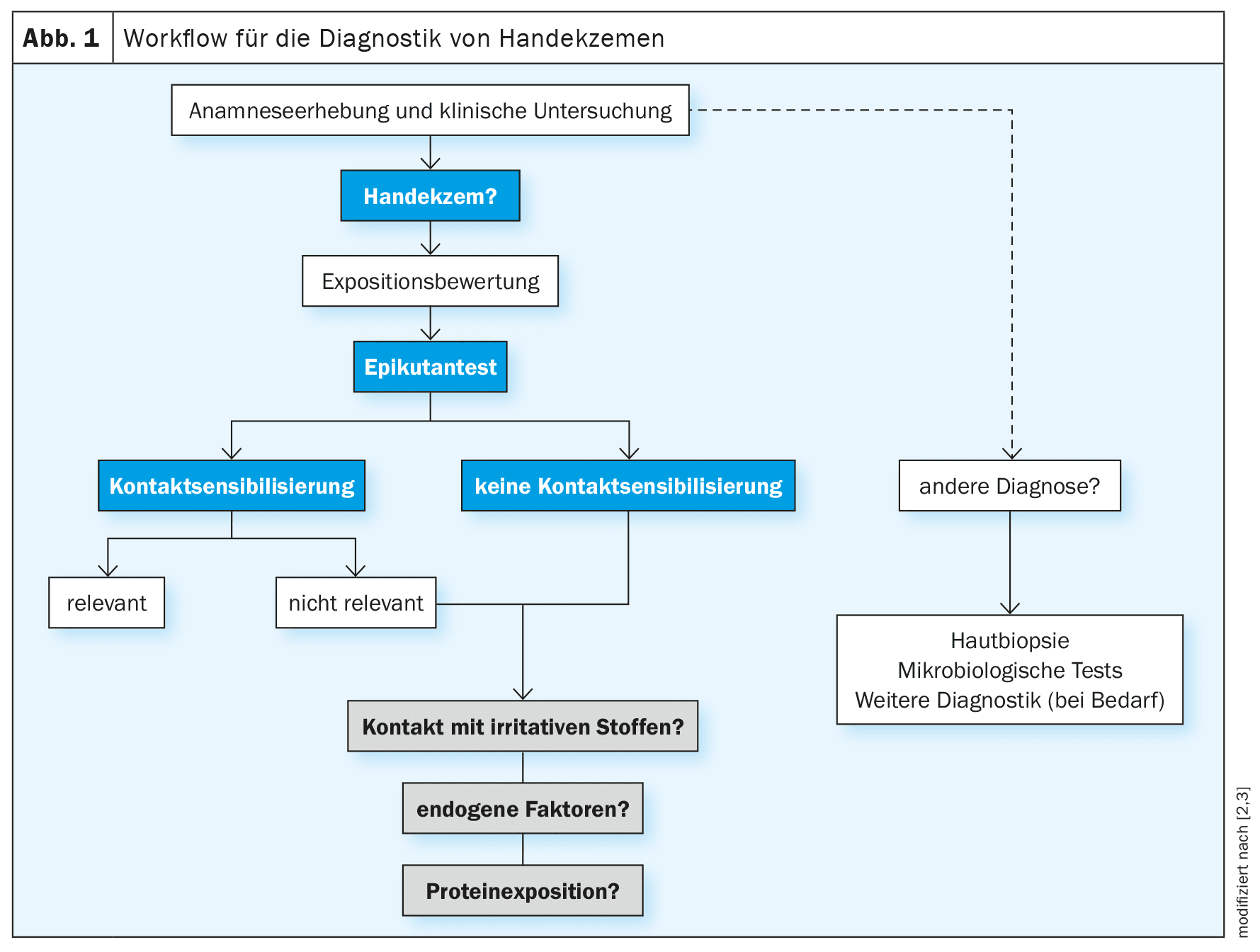

A structured approach is recommended in the diagnosis of hand eczema in order to systematically clarify possible causes. The algorithm recommended by the guideline is schematically outlined in Figure 1 [2,3]. Important diagnostic components are: a detailed medical history including personal and occupational exposure, clinical examination and skin tests. A thorough medical history is essential for any exposure assessment and exposure assessment is a prerequisite for planning prick and epicutaneous tests. The medical history should be taken in a structured manner and contain information on current symptoms, duration and course of the disease. Exacerbations and recurrences in connection with work-related activities and whether there are anamnestic/family anamnestic indications of an atopic diathesis (atopic dermatitis, allergic asthma, allergic rhinoconjunctivitis) should also be asked [2,39,57,58]. In addition, previous and current skin or systemic diseases, regular use of medication and possible nicotine consumption should be ascertained [59]. It may also be helpful for healthcare professionals and patients to provide photographic documentation of episodes of the disease. Furthermore, the guidelines recommend collecting information on previously documented allergic sensitization and test procedures, as well as information on the use of and reaction to topical medications and skin care products, wet work and current and previous exposure to known contact allergens and irritants at work, at home and during leisure time [2,16].

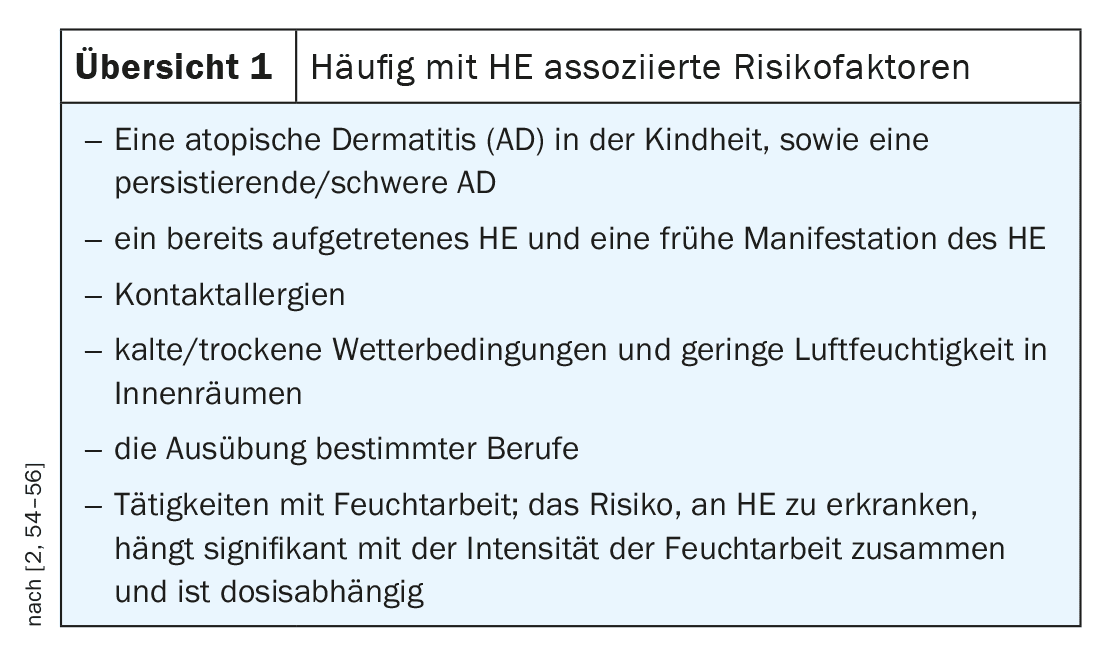

It has been shown that HE is triggered by environmental factors in up to 59% of cases [2,19]. Risk factors frequently associated with HE/CHE include atopic diathesis (Overview 1). The clinical examination includes inspection of the hands and the entire integument, including the feet [2]. The feet are involved in up to 20% of all hand eczema patients [20]. As the clinical manifestations of hand eczema show similarities with a broad spectrum of dermatoses, differential diagnostic considerations are also crucial [21,22]. In the case of allergic contact dermatitis, involvement of the genitals should also be considered.

Exposure assessment, prick and epicutaneous test

For the diagnosis of allergic contact dermatitis , local and temporally relevant allergen exposure and contact sensitization to the suspected allergen(s) must be proven. Irritant contact dermatitis is a diagnosis of exclusion; it requires that other etiologies, in particular allergic contact dermatitis, have been excluded and that exposure to skin irritants is present [2]. Atopic hand eczema can be associated with an inherent impairment of the skin barrier, e.g. filaggrin deficiency. Further indications of atopic hand eczema may be a positive personal history of atopic eczema, atopic eczema in another location (e.g. flexural eczema) or other atopic diseases. Hand eczema due to protein contact dermatitis is rare, the diagnosis is made on the basis of evidence of an immediate type sensitization to a protein (prick test, specific IgE) and an eczema reaction to this protein (usually meat, fish, vegetables and fruit in people who handle food). Protein contact dermatitis can also be accompanied by contact urticaria on the protein.

Exposure assessment: This should include both occupational and domestic exposure, including the use and type of protective equipment and the products used for skin care, personal hygiene and medical and alternative therapies. Exposure assessment is an important tool for the etiologic diagnosis of allergic contact dermatitis, protein contact dermatitis and/or irritant contact dermatitis [4]. The aim is to determine whether recent exposures to allergens and/or irritants have caused the eczema [4]. In addition to assessing whether an occupational disease is present, the exposure assessment is also the basis for preventive measures. If an epicutaneous test shows unexpectedly positive results, it is recommended to repeat the exposure analysis [4]. Modern methods for identifying and quantifying exposure are available for certain allergens [4].

Prick test: a positive prick test is used to detect immediate-type allergies (e.g. natural rubber latex or certain food allergens) and can also be an indication of the presence of atopic eczema [23]. Continued or repeated exposure to incompatible proteins can lead to eczematous reactions known as protein contact dermatitis [2]. If protein contact dermatitis is suspected without systemic symptoms, the prick-to-prick test with fresh protein-containing material (food and plants) is a reliable and important diagnostic procedure. Alternatively, direct exposure to the suspected allergen for about 20 minutes at the site where protein contact dermatitis occurs (e.g. fish or meat on the fingers) can lead to wheals and blisters, which confirms the diagnosis [2,24].

However, the risk of anaphylaxis should always be considered in patients who have experienced generalized symptoms in the past. It is therefore advisable to carry out the test with an appropriate medical history under emergency standby. When evaluating the results, it should be borne in mind that prick-to-prick tests with fresh material can also lead to non-specific positive (irritant) reactions, so that control tests may be useful. Additional information regarding the individual sensitization profile can be obtained by measuring specific IgE antibodies in addition to the prick test. This can confirm the diagnosis of immediate-type hypersensitivity [2,24].

Epicutaneous test (also known as patch test): is considered the gold standard for detecting type IV sensitization (late-type allergies) as the trigger of allergic contact dermatitis and is indicated if the hand eczema has persisted for more than three months, if the symptoms do not respond to therapy or if there is a clinical suspicion of contact allergy [23]. A positive reaction in the epicutaneous test requires a subsequent assessment of the clinical relevance of the identified allergens [23]. If occupational triggers are identified, the patient’s workplace should be checked. As allergic contact dermatitis of the hands can only be healed by consistently avoiding the triggering substances, it is important to provide patients with comprehensive information about the type of contact allergens and their occurrence [2]. It should be borne in mind that a negative epicutaneous test alone does not mean absolute exclusion of contact sensitization, as false-negative reactions are possible and it is not always guaranteed that all potential allergens have been included.

Microbiological and molecular diagnostics

If there are indications of a secondary infection during the clinical examination, a skin swab can be used to obtain information about the causative microorganism and antibiotic resistance [2]. In most cases, secondary infections are due to Staphylococcus aureus (S. aureus) and occur as an accompanying or aggravating factor of hand eczema, particularly in atopic patients. Antibiotic treatment should only be considered if there are signs of a clinical infection [2,25]. Furthermore, a possible dermatophyte infection (tinea) or yeast infection (candidiasis) should be ruled out; unilateral cases of hand eczema are particularly suspicious. For diagnostic purposes, skin swabs/scale material should be taken for microscopy and culture and – if available – for polymerase chain reaction (PCR) [26]. In the case of dermatophyte infections in the hands, the feet may also be affected. In addition, scabies should be considered as a possible differential diagnosis. In rare cases, typically when blisters form on a finger, the possibility of a herpes simplex infection should also be considered [2,27].

For cases in which it proves difficult to differentiate clinically and histologically between hand eczema vs. psoriasis palmaris, it has been possible for some years to use the “Molecular Classifier ” in the field of molecular diagnostics, which ensures a better differentiation based on the disease-specific expression of the genes NOS2 and CCL27 in the skin biopsy [28,29]. Alternatively, the molecular profile of different aetiologies and clinical/morphological subtypes of hand eczema can now also be analyzed without a skin biopsy by using epidermal adhesive strips in conjunction with whole transcriptome sequencing and global proteome analysis [2,30,31].

Treatment according to the step-by-step scheme

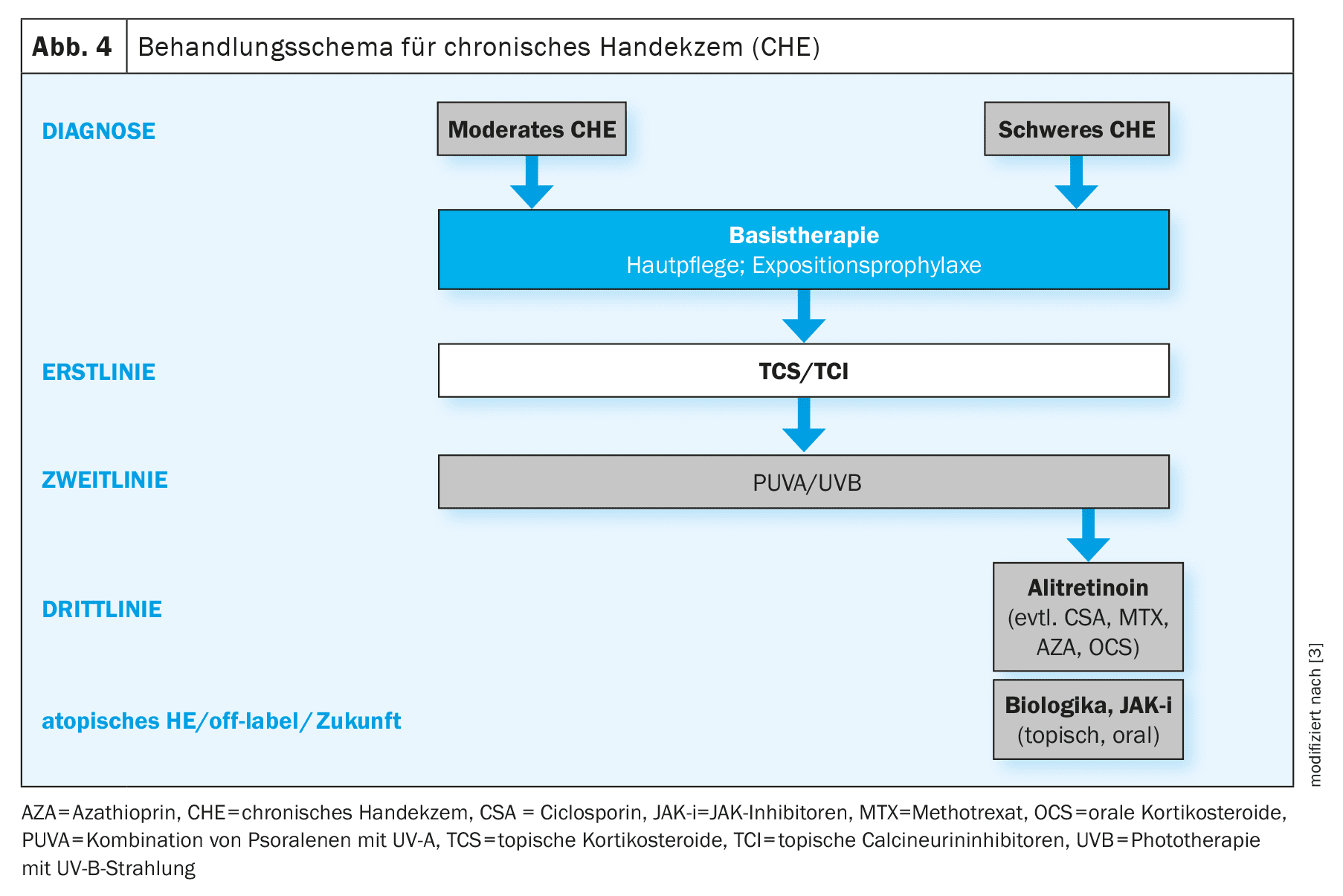

The treatment of HE/CHE is based on a staged approach and includes various treatment components depending on morphology and severity (Fig. 4) [2]. The hand eczema severity index (HECSI) score or the validated photographic guide can be used to assess severity [2,23]. The adapted Photographic guide contains 16 photographs categorized into four severity groups: almost appearance-free, moderate, severe and very severe, was used to assess the self-reported severity of HE [32]. The HECSI gives a total score from 0 to 360 points based on the assessment of the severity of six different morphological signs and the extent of eczema in five areas of the hands (healed = 0; almost healed = 1-16; moderate =

17-37; severe = 38-116; very severe = ≥117) [33]. In clinical studies, the HECSI, a validated morphology-based severity assessment, is the most commonly used objective assessment tool [34,35].

Basic care and exposure prophylaxis: Regardless of the severity, in addition to general protective measures and exposure prophylaxis, consistent basic care (e.g. with products containing urea, lactic acid derivatives or glycine) is recommended to provide the skin with moisture and lipids, which contributes to the regeneration of the skin barrier after skin exposure [36,37]. Important criteria for the choice of skin care products are patient preferences and any existing (contact) allergies [2].

Topical anti-inflammatory therapy/phototherapy: There are currently no topical anti-inflammatory therapy options specifically approved for HE/CHE. For first-line treatment of moderate to severe CHE, guidelines recommend the use of topical corticosteroids (TCS) of potency I-IV [3,23]. The treatment of moderate to severe CHE is complex and requires a long-term therapeutic strategy [38]. A combination of irritative, allergic and endogenous factors is often present, which explains the chronic course and the often unsatisfactory response to therapy [3,23]. Due to the risk of skin atrophy, long-term TCS use is not recommended [3]. In addition, TCS may not offer benefit for all CHE subtypes, as there is evidence that patients with irritant contact dermatitis respond inadequately and irritant contact dermatitis is involved in some form in a majority of CHE cases [15]. As a steroid-sparing option, the topical calcineurin inhibitor (TCI) tacrolimus (ointment, 0.1%) can be used in the short term [3]. In adult patients with moderate to severe CHE that proves refractory to TCS/TCI, phototherapy (topical PUVA, narrow-band UVB, UVA1) of the hands should be used [2]. Due to the risk of side effects with long-term use as a result of the cumulative UV dose, phototherapy is not suitable for long-term treatment.

Systemic therapy: Alitretinoin is currently the only systemic therapy specifically approved for CHE in Switzerland and can be used for adults with severe CHE who do not respond sufficiently to treatment with topical preparations and/or phototherapy [2,3,40]. Alitretinoin is an active ingredient from the retinoid group and is administered in the form of capsules. Headache is the most common adverse effect, which usually occurs at the beginning of treatment with alitretinoin and in many cases subsides after 1-2 weeks [41]. Other possible side effects include an increase in plasma cholesterol and triglyceride levels and a decrease in thyroid function parameters, so these parameters should be monitored during treatment and countermeasures taken if necessary [2,17]. Like other active substances in the retinoid class, alitretinoin is also teratogenic, meaning that safe contraception measures and regular pregnancy tests are indicated before, during and for one month after the end of treatment in women of childbearing age [2].

Oral glucocorticoids (maximum three weeks, starting at 0.5 mg/kg/day), acitretin, ciclosporin, azathioprine and methotrexate are sometimes used off-label [2]. Acitretin is also a retinoid and therefore teratogenic. Treatment with ciclosporin requires careful monitoring as it can be associated with potentially serious adverse events. Overall, there is a great need for well-tolerated, steroid-free treatment alternatives that can also be used in the long term.

New findings on the effects of different active substances in different subgroups of CHE patients can contribute to the optimization of treatment options [4]. This requires more data from well-controlled studies. One hypothesis, for example, is that Th2-triggered forms of CHE show a good response to Th2-targeted therapies such as dupilumab or tralokinumab [2,4]. In addition to biologics, JAK inhibitors (in oral or topical form) are also currently the subject of research.

Further explanations on the management of CHE are summarized in the interview .

Chronic hand eczema in a socio-occupational context

Hand eczema as an occupational skin disease, i.e. symptoms triggered or exacerbated by exposure at the workplace, is widespread [2,42,43]. Statistics from Swiss accident insurers show that around one in six recognized occupational illnesses is associated with a skin disease** [44]. Contact eczema accounts for around 90% of recognized occupational skin diseases [45]. In terms of the etiology of occupational hand eczema, irritant and allergic subtypes are the most common [42]. An atopic disposition is the best known and most important predisposing factor and is found in one third to one half of cases of occupational hand eczema [23,46,47].

** Status of the information 07.10.2024

Common triggers of irritant contact dermatitis are exposure to wet work, food, gloves or oils, where hand eczema severity index influences the incidence of irritant contact dermatitis with duration and intensity of exposure [23]. Possible causes of allergic contact dermatitis include exposure to allergens such as chromate, nickel, biocides and rubber chemicals [23]. It is not uncommon for a combination of irritant, allergic and endogenous factors to be present, which explains both the chronic course and the often unsatisfactory response to therapy [23].

Certain occupational groups are associated with an increased risk of developing hand eczema, including [48]:

- Wet work occupations (hairdressers, cleaners, healthcare workers, metalworkers, dental technicians)

- Occupations with more mixed exposure in the food industry (bakers, butchers)

- Florists, cashiers, electroplaters, machine operators and employees in construction and metal surface treatment [49–51].

In a multicenter study, 28% of hand eczema patients developed an inability to work and in 12% of cases this lasted longer than 12 weeks [52]. In a Danish prospective study, severe occupational hand eczema, age of 40 years or more and severely impaired HRQoL at baseline were predictors of long-term work disability and unemployment [8]. Common European minimum standards for the prevention and treatment of occupational skin diseases have been developed, including minimum requirements for workplace exposure assessment [4].

With regard to the context in Switzerland, SUVA (Swiss National Accident Insurance Fund) provides numerous information materials on its website, e.g. a detailed brochure on the prevention of occupational skin diseases [53]: www.suva.ch/hautschutz.

Occupational dermatoses are primarily skin diseases that have been caused exclusively or predominantly by harmful substances or specific work in the course of occupational activity [53]. Dermatology patients who have been diagnosed with occupational HE/CHE should register an occupational disease with SUVA or a private accident insurance company in cooperation with their employer [45]. If the hand eczema is recognized as an occupational disease by the insurer, the costs, e.g. for the associated investigations, treatment and loss of earnings, will be covered by the insurer. In addition, SUVA/private accident insurance can suggest prophylactic measures for the workplace. If all general and therapeutic measures have been exhausted and the CHE persists, a “non-suitability order” can be issued. Under certain conditions, this qualifies for retraining by the disability insurance (IV) or is a prerequisite for financial supplementary benefits (transitional benefits).

Take-Home-Messages

- Hand eczema (HE) and especially chronic hand eczema (CHE) are very stressful for those affected and are associated with a reduced quality of life.

- The s2k guideline updated in 2023, which is based on the current ESCD guideline, provides a comprehensive overview of evidence-based recommendations for the diagnosis and treatment of hand eczema (HE)/chronic hand eczema (CHE).

- From an etiological point of view, HE/CHE is classified as allergic contact dermatitis, irritant contact dermatitis, atopic hand eczema and protein contact dermatitis, with mixed forms frequently occurring.

- The guideline recommends a step therapy regimen for the treatment of HE/CHE. TCS are considered “first-line” therapy. The only approved systemic therapeutic agent for the severe form is currently alitretinoin. Various biologics and JAK inhibitors are currently being researched.

- HE/CHE has a high socio-medical significance. Occupational hand eczema is widespread in certain occupational groups. In Switzerland, employees should report occupational HE/CHE to SUVA or a private accident insurance company.

Literature:

- Quaade AS, et al: Prevalence, incidence, and severity of hand eczema in the general population – a systematic review and meta-analysis. Contact Dermatitis 2021; 84(6): 361-374.

- S2k guideline “Diagnosis, prevention and therapy of hand eczema”, AWMF register no.: 013-053, status: 23/02/2023, valid until: 22/02/2028.

- Thyssen J, et al: Guidelines for diagnosis, prevention, and treatment of hand eczema. Contact Dermatitis 2022; 86(5): 357-378.

- “Care landscape of chronic hand eczema: status quo, challenges and occupational dermatology?”, Prof. Dr. med. Christoph Skudlik, continuing education, www.cme-kurs.de/kurse/chronisches-handekzem-status-quo-herausforderungen-berufsdermatologie-2,(last accessed 03.10.2024).

- Nørreslet LB, et al: Impact of hand eczema on quality of life: metropolitan versus non-metropolitan areas. Contact Dermatitis 2018; 78(5): 348-354.

- Silverberg JI, et al: Chronic Hand Eczema Guidelines From an Expert Panel of the International Eczema Council. Dermatitis 2021;32(5): 319-326.

- Quaade AS, et al: Chronic hand eczema: A prevalent disease in the general population associated with reduced quality of life and poor overall health measures. Contact Dermatitis 2023; 89(6): 453-463.

- Cvetkovski RS, et al: Quality of life and depression in a population of occupational hand eczema patients. Contact Dermatitis. 2006; 54: 106-111.

- Moberg C, Alderling M, Meding B: Hand eczema and quality of life: a population-based study, 2009 study. BJD 2009; 161(2): 397-403.

- Agner T, et al: Hand eczema severity and quality of life: a cross-sectional, multicenter study of hand eczema patients. Contact Dermatitis 2008; 59: 43-47.

- Marron SE, et al: The psychosocial burden of hand eczema: Data from a European dermatological multicenter study. Contact Dermatitis 2018; 78: 406-412.

- Grant L, et al: Development of a conceptual model of chronic hand eczema (CHE) based on qualitative interviews with patients and expert dermatologists. Adv Ther 2020; 37(2): 692-706.

- Molin S: Pathogenesis of hand eczema [Pathogenesis of hand eczema]. Dermatologist 2019; 70(10): 755-759.

- Diepgen TL, et al: Guideline on the management of hand eczema ICD 10 Code: L20. L23. L24. L25. L30. JDDG 2009; 7 Suppl 3: S1-16.

- Agner T, et al. : Classification of hand eczema. JEADV 2015; 29: 2417-2422.

- Agner T, Elsner P. Hand eczema: epidemiology, prognosis and prevention. JEADV 2020; 34 Suppl 1: 4-12.

- Menné T, et al: Hand eczema guidelines based on the Danish guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of hand eczema. Contact Dermatitis 2011; 65: 3-12.

- Molin S, et al: Diagnosing chronic hand eczema by an algorithm: a tool for classification in clinical practice. Clin Exp Dermatol 2011; 36: 595-601.

- Lerbaek A, et al: Heritability of hand eczema is not explained by comorbidity with atopic dermatitis. J Invest Dermatol 2007; 127: 1632-1640.

- Agner T, et al: Factors associated with combined hand and foot eczema. JEADV 2017; 31: 828-832.

- Mahler V: Hand dermatitis–differential diagnoses, diagnostics, and treatment options. JDDG 2016; 14: 7-26; quiz 27-8.

- Antonov D, Schliemann S, Elsner P: Hand dermatitis: a review of clinical features, prevention and treatment. Am J Clin Dermatol 2015; 16: 257-270.

- Herloch V, Elsner P. The (new) occupational disease no. 5101: “Severe or recurrent skin diseases”. JDDG 2021 May; 19(5):720-742. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/ddg.14537_g.

- Dickel H. Exceptional occupational allergies caused by foods of animal origin. The dermatologist. 2021; 72: 493-501.

- Haslund P, et al: Staphylococcus aureus and hand eczema severity. Br J Dermatol. 2009; 161: 772-777.

- Wiegand C, et al: Are the classic diagnostic methods in mycology still state of the art? JDDG 2016; 14: 490-494.

- Fatahzadeh M, Schwartz RA: Human herpes simplex virus infections: epidemiology, pathogenesis, symptomatology, diagnosis, and management. JAAD 2007; 57: 737-763.

- Quaranta M, et al: Intraindividual genome expression analysis reveals a specific molecular signature of psoriasis and eczema. Sci Transl Med 2014; 6: 244ra90.

- Garzorz-Stark N, et al: A novel molecular disease classifier for psoriasis and eczema. Exp Dermatol 2016; 25: 767-774.

- Sølberg JBK, et al: The transcriptome of hand eczema assessed by tape stripping. Contact Dermatitis 2022; 86: 71-79.

- Sølberg JBK, et al: The proteome of hand eczema assessed by tape stripping. J Invest Dermatol 2023 Aug; 143(8): 1559-1568.e5.

- Coenraads PJ, et al: Construction and validation of a photographic guide for assessing severity of chronic hand dermatitis. BJD 2005; 152: 296-301.

- Held E, et al: The hand eczema severity index (HECSI): a scoring system for clinical assessment of hand eczema. A study of inter- and intraobserver reliability. BJD 2005; 152(2): 302-307.

- Weistenhöfer W, et al: An overview of skin scores used for quantifying hand eczema: a critical update according to the criteria of evidence-based medicine. BJD 2010; 162(2): 239-250.

- Rönsch H, et al: Which outcomes have been measured in hand eczema trials? A systematic review. Contact Dermatitis 2019; 80(4): 204-207.

- Williams C, et al: A double-blind, randomized study to assess the effectiveness of different moisturizers in preventing dermatitis induced by hand washing to simulate healthcare use. BJD 2010; 162: 1088-1092.

- De Paépe K, et al: Beneficial effects of a skin tolerance-tested moisturizing cream on the barrier function in experimentally-elicited irritant and allergic contact dermatitis. Contact Dermatitis 2001; 44: 337-343.

- Elsner P, Agner T: Hand eczema: treatment. JEADV 2020 Jan; 34 Suppl 1: 13-21.

- Berndt U, et al: Role of the atopy score and of single atopic features as risk factors for the development of hand eczema in trainee metal workers. BJD 1999; 140: 922-924.

- Lee GR, et al: Current and emerging therapies for hand eczema. Dermatol Ther 2019; 32(3): e12840.

- Bissonnette R, et al: Successful retreatment with alitretinoin in patients with relapsed chronic hand eczema. BJD 2010; 162: 420-426.

- Elsner P, Schliemann S. Treatment according to a step-by-step scheme. Dtsch Dermatolog 2023;71(1):44-55.

- Skudlik C, John SM: Occupational Dermatoses. In: Plewig G et al (Eds). Braun-Falco’s Dermatology. Springer, Berlin Heidelberg 2022: 539-549.

- “Skin diseases at work are more common than you think”, www.suva.ch/de-ch/praevention/nach-gefahren/gefaehrliche-materialien-strahlungen-und-situationen/hautschutz-am-arbeitsplatz/berufliche-hautkrankheiten-frueh-erkennen,(last accessed 07.10.2024).

- “Chronic hand eczema”, patient information. University Hospital Zurich, Dermatology Clinic, www.usz.ch/app/uploads/2020/

07/A5_BR_Handekzem_Digital-23.9.2019.pdf, (last accessed 07.10.2024). - Hogan DJ, Dannaker CJ, Maibach HI: The prognosis of contact dermatitis. JAAD 1990; 23(2 Pt 1): 300-307.

- Coenraads PJ, Diepgen TL: Risk for hand eczema in employees with past or present atopic dermatitis. Int Arch Occup Environ Health 1998; 71(1): 7-13.

- Alfonso JH, et al: Minimum standards on prevention, diagnosis and treatment of occupational and work-related skin diseases in Europe – position paper of the COST Action StanDerm (TD 1206). JEADV 2017; 31 Suppl 4: 31-43.

- Vindenes HK, et al: Prevalence of, and work-related risk factors for, hand eczema in a Norwegian general population (The HUNT Study). Contact Dermatitis 2017; 77: 214-223.

- Lukács J, Schliemann S, Elsner P: Association between smoking and hand dermatitis – a systematic review and meta-analysis. JEADV 2015; 29: 1280-1284.

- Bauer A, et al: [Contact allergies in the German workforce : Data of the IVDK network from 2003-2013]. Dermatologist 2015; 66: 652-664.

- Diepgen TL, et al: Hand eczema classification: a cross-sectional, multicentre study of the aetiology and morphology of hand eczema. BJD 2009; 160: 353-358.

- “Skin protection: How to avoid skin injuries and skin diseases”, www.suva.ch/hautschutz,(last accessed 07.10.2024).

- Ruff SMD, et al: The association between atopic dermatitis and hand eczema: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BJD 2018; 178: 879-888.

- Heede NG, et al: Predictive factors of self-reported hand eczema in adult Danes: a population-based cohort study with 5-year follow-up. BJD 2016; 175: 287-295.

- Lund T, et al: Risk of work-related hand eczema in relation to wet work exposure. Scand J Work Environ Health 2020; 46: 437-445.

- Diepgen TL, Fartasch M, Hornstein OP: Criteria for the assessment of atopic skin diathesis. [Criteria of atopic skin diathesis]. Dermatoses in Occupation and Environment 1991; 39: 79-83.

- Diepgen TL, Sauerbrei W, Fartasch M: Development and validation of diagnostic scores for atopic dermatitis incorporating criteria of data quality and practical usefulness. J Clin Epidemiol 1996; 49: 1031-1038.

- Molin S, Ruzicka T, Herzinger T: Smoking is associated with combined allergic and irritant hand eczema, contact allergies and hyperhidrosis. JEADV 2015; 29: 2483-2486.

DERMATOLOGY PRACTICE 2024; 34(5): 4-12