Nail psoriasis is the most common inflammatory dermatosis of the nail apparatus. Most often, but not always, nail infestation occurs together with skin psoriasis. Typical psoriasiform nail changes include spotted nails, oil spots, onycholysis, hyperkeratosis, and longitudinal and transverse grooves. Most clinical features are visible to the naked eye; in unclear cases, “nail clipping” and imaging studies can help improve morphologic assessment. Since nail psoriasis is a predictor of psoriatic arthritis, screening for joint involvement is very important.

On the occasion of this year’s annual meeting of the European Academy of Dermatology and Veneorology (EADV) in Milano, Prof. Bertrand Richert, M.D., Université Libre de Bruxelles, Brussels (Belgium), spoke about the diagnostic work-up in patients with suspected nail psoriasis. Frequently, nail infestation (psoriasis unguium) occurs in combination with lesions of the skin, but in 6-10% it is an isolated symptom [1]. With concurrent plaque psoriasis, nail psoriasis is associated with a higher severity, but nail infestation may also occur with mild psoriasis [2,3]. If isolated nail psoriasis is suspected, onychomycoses must first be excluded (in about 50% of nail dystrophies, these are fungal infections). Onycholysis and hyperkeratosis in the fingernails is more suggestive of psoriasis, while infestation of the toes is somewhat more likely to be onychomycosis [1]. However, fungal detection does not rule out underlying nail psoriasis, as fungal or bacterial infections manifest in 4.6-30% of patients with nail psoriasis [4,5]. In addition to onychomycoses, nail dystrophies may also be manifestations of lichen ruber of the nail organ or paraungual eczema. But also tumors (e.g. subungual melanoma), as well as congenital and acquired nail dystrophies have to be considered in the differential diagnosis.

Clinical appearance

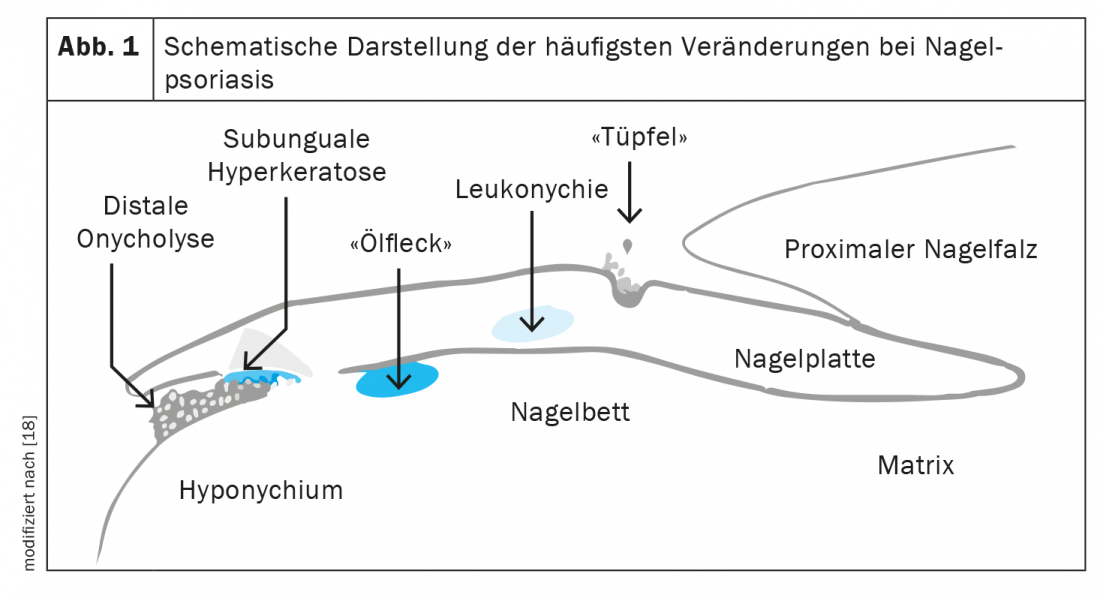

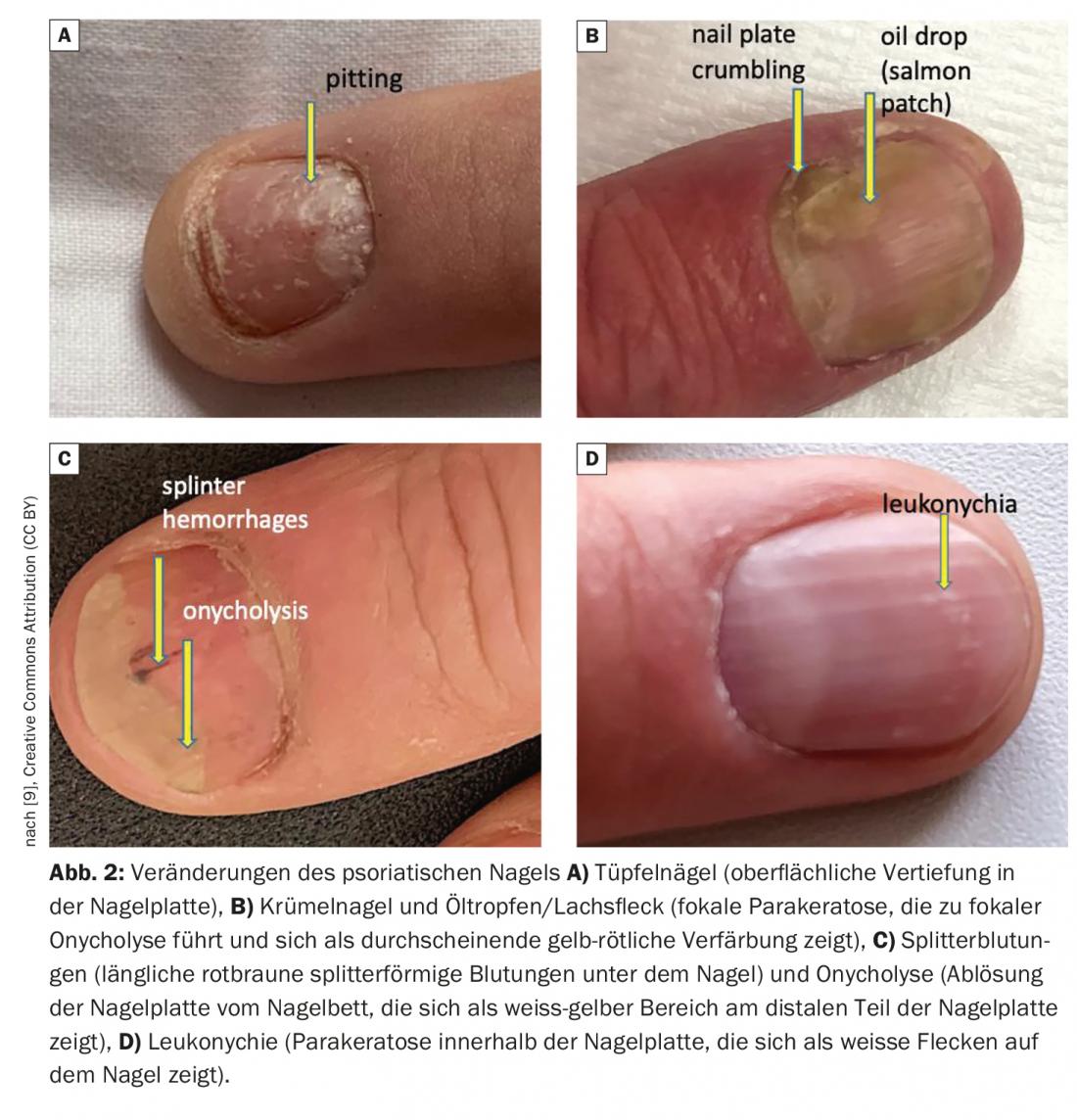

The clinical features of nail psoriasis vary depending on which structure of the nail apparatus is affected (Fig. 1) [6]. Involvement of the nail matrix typically results in spotted nails (the most common finding in nail psoriasis) (Fig. 2A). The spots are small parakeratosis foci of the nail surface [7]. When the loose parakeratosis breaks out, dimples appear, these are small, regular depressions of the nail plate surface [7]. Other forms of manifestation in the area of the nail matrix are onychodystrophies and leukonychia (Fig. 2D). In contrast, the “oil drops” (Fig. 2B) represent psoriatic lesions in the distal matrix and in the nail bed [6,8]. The epithelium is characterized by marked parakeratosis and dilated capillaries in the papillae [7]. Circumscribed blood inclusions at the heights of the subungual keratosis just below the nail plate are visible macroscopically as splinter hemorrhages (narrow black lines from the tip to the cuticle) (Fig. 2C) [7]. Psoriatic paronychia (nail bed inflammation) is possible with psoriatic infestation in the periungual region [6]. In severe inflammatory lesions, combined nail matrix and nail bed psoriasis may develop, forming a “psoriatic crumb nail” (Fig. 2B) [8]. Dermoscopically, irregularly distributed, dilated, tortuous, elongated capillaries are typically seen in the hyponychium in nail psoriasis.

Unclear clinical findings: what next?

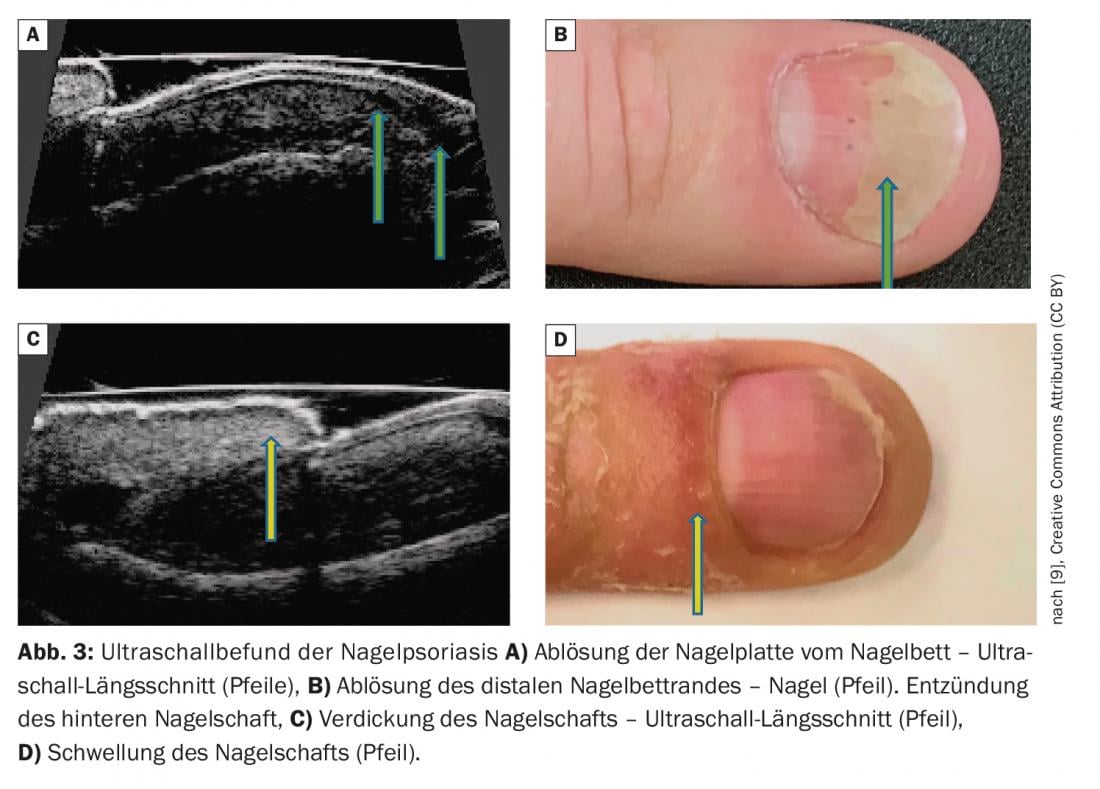

Noninvasive imaging techniques can visualize characteristic morphologic features that complement clinical assessment [1]. In addition to onychoscopy and videodermatoscopy, ultrasonography of the nail apparatus also provides helpful information for morphologic evaluation (Fig. 3) [9]. In addition, studies have sonographically identified features of finger extensor tendon enthesopathy at the base of the distal phalanx in more than half of psoriatic arthritis patients with nail psoriasis [9]. A typical finding for nail psoriasis on videodermatoscopy is dilated capillaries in the hyponychium. [10]. In clinically unclear cases, the collection of a nail sample by “nail clipping” with subsequent histopathological and immunohistochemical examination may also be informative. Immunohistochemical staining (e.g. Giemsa or toluidine blue) can be used to visualize hyperkeratosis and parakeratosis.

Severity assessment

Nail psoriasis can be acute or chronic and have different degrees of severity. Infestation of the nails can occur on one as well as on all fingers and toes and can lead to the loss of the nail [11]. For the objective assessment of the severity of nail psoriasis and for the evaluation of the progression, the Nail Psoriasis Severity Index (NAPSI) has been established in clinical studies [12]. The NAPSI score assesses the quadrants of the nails, with changes in the nail bed and nail matrix assessed independently [6]. The individual values from 0 to 4 are added up for each nail. Thus, each hand and foot reaches a maximum score of 40. In total, the NAPSI for all nails together is thus between 0 and 160. The higher the value of the NAPSI score, the more severely the nails are affected by psoriasis. Alternatively, the NAPPA score (Nail Assessment in Psoriasis and Psoriatic Arthritis) can be used [13]. This procedure records on the one hand the pathological nail changes, and on the other hand the physical, psychological and social concomitant complaints of the patient.

Screening for joint involvement is critical

Nail psoriasis is not only an aesthetic problem, it can also lead to functional limitations of the hands. Moreover, nail psoriasis (like scalp psoriasis and perianal involvement) is associated with psoriatic arthritis [14]. In patients with nail psoriasis, especially with onycholytic nail changes, the risk of developing joint involvement is three times higher compared to psoriasis patients without nail involvement, Prof. Richert emphasized [1]. Therefore, patients with onycholysis in particular should always be asked about joint pain, which occurs preferentially in the morning [1,15]. The speaker recommends initiating a referral to a rheumatologist at the slightest hint of joint involvement. Joint involvement can be detected at an early stage by means of imaging techniques (MRI, ultrasound) [16]. Whether or not joint involvement is present has implications relevant to therapy. A positive family history for psoriatic arthritis is seen in about half of patients with skin psoriasis and nail involvement [17].

Congress: EADV Annual Meeting

Literature:

- “Nail psoriasis: how to make a diagnosis,” Prof. Bertrand Richert, MD, Presentation ID D3T11.1C, EADV Annual Meeting, 07-10/09/22,

- Augustin M, et al: Disease severity, quality of life and health care in plaque-type psoriasis: a multicenter cross-sectional study in Germany, Dermatology 2008; 216(4): 366-372.

- Augustin M, et al: Br J Dermatol 2010; 163(3): 580-585.

- Nenoff P, et al. S1 Guideline Onychomycosis (AWMF Register No. 013-003), 2022, www.awmf.org/leitlinien/detail/ll/013-003.html, last accessed Sept. 20, 2022.

- Natarajan V, et al: Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol 2010; 76(6): 723.

- Painsi C: Therapeutic options for nail psoriasis, DFP literature review, www.oeadf.at/files/E-Learning/ClinicumDerma_11_052017.pdf, (last accessed 20/09/2022).

- e.Medpedia: Histopathology of the skin: diseases of the nails, www.springermedizin.de/emedpedia/histopathologie-der-haut/krankheiten-der-naegel?epediaDoi=10.1007%2F978-3-662-44367-5_21 (last accessed 09/20/22).

- Oram Y, Akkaya AD. Dermatol Res Pract 2013; 2013: 180496.

- Krajewska-Wlodarczyk M, Owczarczyk-Saczonek A: Int J Environ Res Publich Health 2022; 19: 5611.

- Iorizzo M, et al: JAAD 2008; 58(4): 714-715.

- WHO: Global Report on Psoriasis, 2016, http://apps.who.int,(last accessed Sept. 20, 2022).

- Rich P, Scher RK: JAAD 2003; 49(2): 206-212.

- Augustin M, et al:. Br J Dermatol. 2014; 170: 591-598.

- Wilson FC, et al: Arthritis Rheum 2009; 61: 233-239.

- Love TJ, et al: J Rheumatol 2012; 39: 1441-1444.

- Bagel J, Schwartzman S: Am J Clin Dermatol 2018; 19(6): 839-852.

- Armesto S, et al: Actas Dermosifiliogr 2011; 102: 365-372.

- Christophers E, Mrowietz U, Sterry W: Psoriasis. 2nd updated and expanded edition. 2002. Thieme: Stuttgart.

DERMATOLOGIE PRAXIS 2022; 32(5): 49-50