The European Society for Clinical Nutrition and Metabolism (ESPEN) defines ME as a nutritional state in which energy, protein, and micronutrient deficiencies result in altered body composition (decreased muscle mass) and reduced physical as well as mental function. In industrialized countries, one in three patients is at risk of ME or has manifest ME on hospital admission. ME has been called “one of the most important hidden causes of health care cost increases.”

Hippocrates of Kos, the father of modern medicine, attributed great importance to nutrition already in the fourth century B.C.: “[…] let your food be your medicine and your medicine be your food.” Nowadays, the negative clinical effects of disease-associated malnutrition (ME) are well studied: longer hospital stay, lower quality of life, higher morbidity and mortality rates. ME is described as “one of the most important hidden causes of cost increases in the health care system” [Neue Zürcher Zeitung, June 11, 2002].

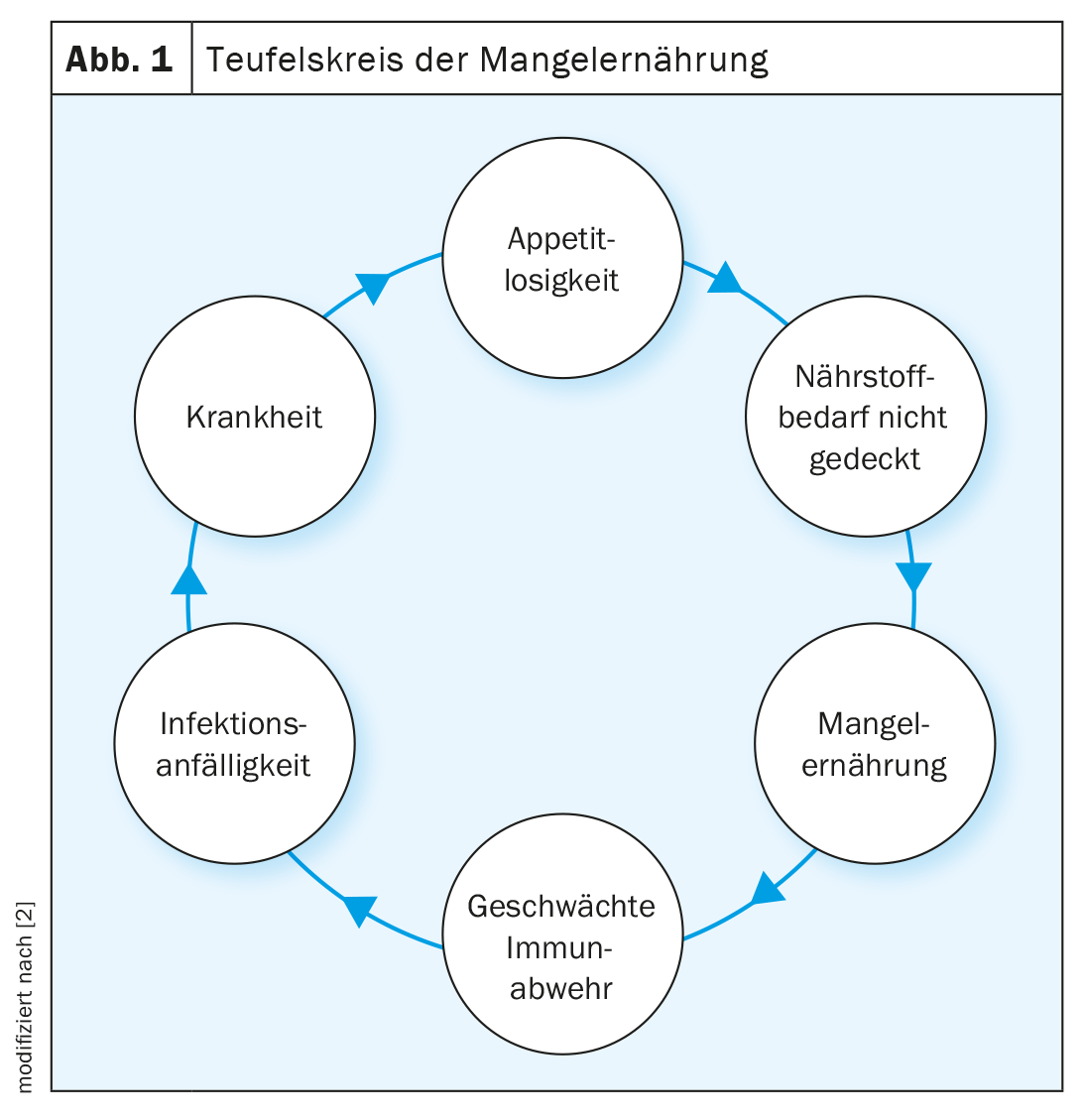

The European Society for Clinical Nutrition and Metabolism (ESPEN) defines ME as a nutritional state in which energy, protein, and micronutrient deficiencies result in altered body composition (decreased muscle mass) and reduced physical as well as mental function [1]. In industrialized countries, one in three patients is at risk of ME or has manifest ME on hospital admission. These patients usually continue to lose weight during the course of hospitalization, which worsens their nutritional status. Multiple factors influencing this progressive, unintentional weight loss include loss of appetite, inflammatory status, protein catabolism, hormonal dysfunction, gastrointestinal distress, physical inactivity, and psychological fatigue (Fig. 1). On average, 2% of the elderly population is malnourished and 24% is at risk of ME. In frail individuals, the prevalence was significantly higher at 9% and 45%, respectively [3]. Loss of appetite is a physiologic response to acute illness, but it can lead to potentially drastic energy and protein deficiencies. ME and disease influence each other, whereby on the one hand the disease can result in ME and on the other hand the ME can negatively influence the course of the disease. Combined with an endocrine and inflammatory stress response, energy, protein, and micronutrient deficiencies can lead to muscle and strength loss and decreased body function, especially in the chronically ill. In acute illness, on the other hand, loss of appetite can act as a protective mechanism and increase autophagy (the body’s mechanism for breaking down damaged cell organelles and toxic products), which can promote recovery. Thus, suppression of autophagy by nutritional therapy in acute disease elicits potentially negative effects. However, in chronically ill patients, this physiological protective mechanism can lead to disease-associated ME. In patients with multiple chronic diseases of mild severity and deteriorating nutritional status, adequate nutritional therapy has a positive effect on clinical outcome. Such patients may have more efficient metabolism and nutrient utilization due to low insulin resistance than acutely ill patients [4]. To improve clinical outcome and enhance well-being, implement individualized, personalized nutritional therapy. Important aspects include the timing of nutritional therapy, the method of administration, and the amount and nutrient selection.

Current evidence situation

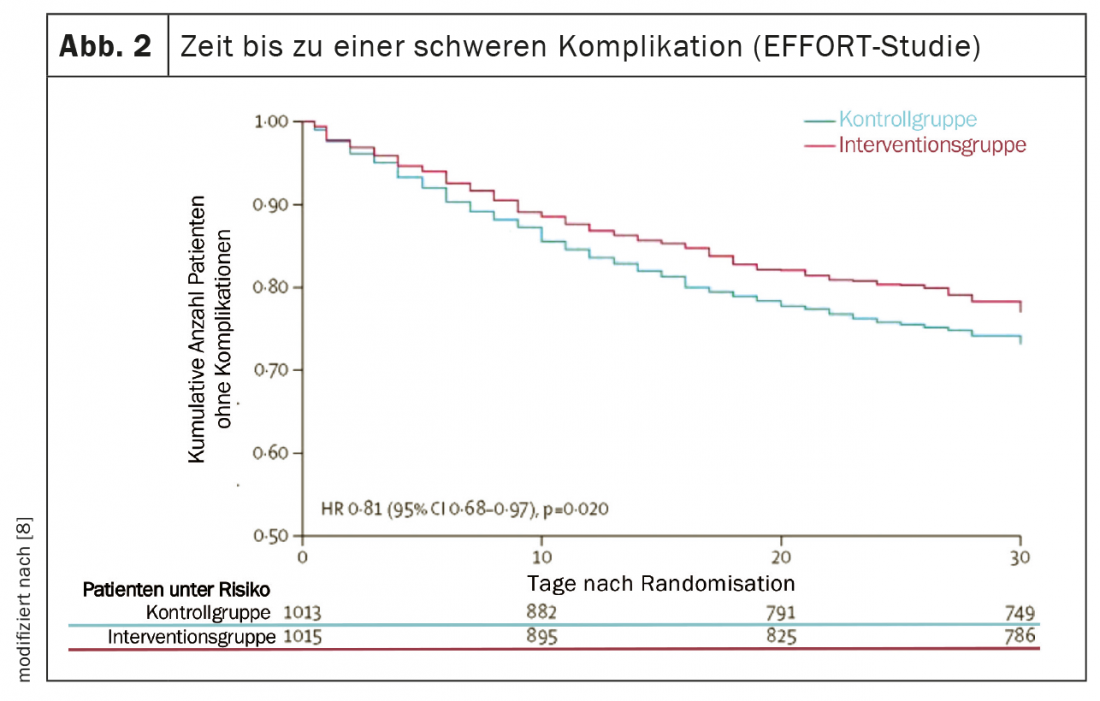

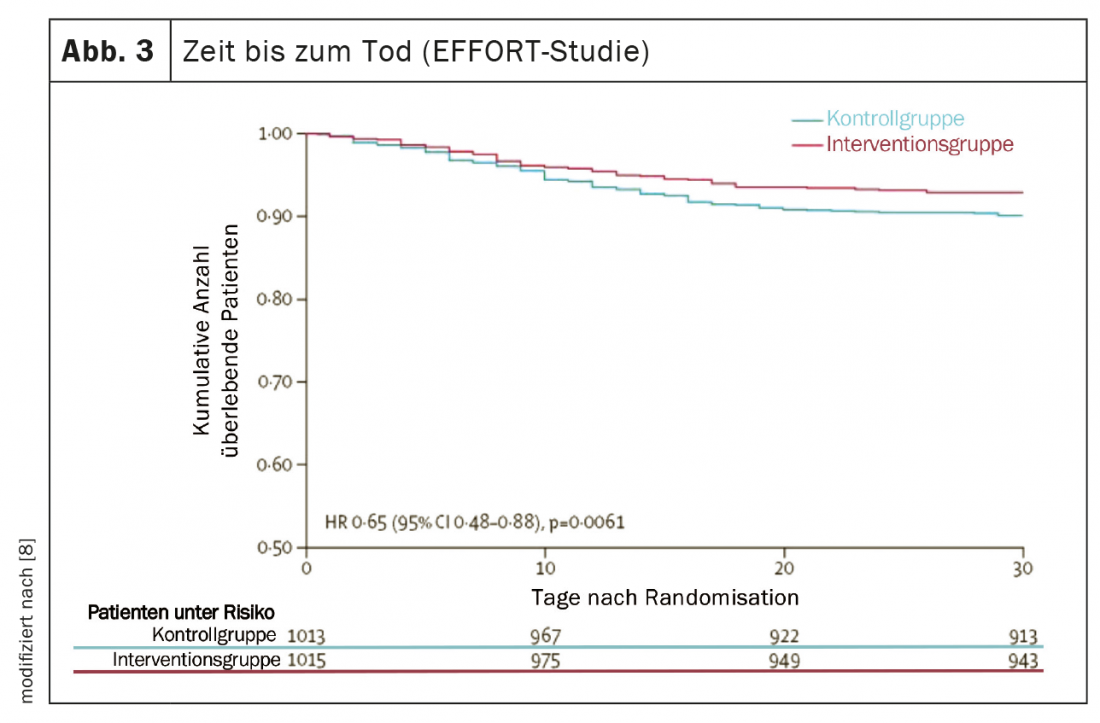

Several high-quality studies have provided important new insights over the past five years that have significantly advanced nutritional medicine and translated nutritional research findings into practice [5]. The PREDIMED (Prevención con Dieta Mediterránea) study provided robust evidence that a Mediterranean diet supplemented with extra virgin olive oil or mixed nuts reduced the risk of cardiovascular and metabolic disease by approximately 30% over five years [6]. Two multicenter randomized controlled trials demonstrated the high efficacy of adequate nutrition therapy in malnourished patients both in hospital and after discharge [7,8]. First, the placebo-controlled NOURISH (Nutrition effect On Unplanned ReadmIssions and Survival in Hospitalized patients) trial of 652 malnourished older adults showed that high protein oral nutritional supplementation can significantly reduce 90-day mortality with a Number Needed to Treat (NNT) of 20 [7]. On the other hand, the EFFORT study (Effect of early nutritional support on Frailty, Functional Outcomes and Recovery of malnourished medical in patients Trial) with 2028 inpatients suffering from malnutrition in eight Swiss hospitals showed the effectiveness of an algorithm-controlled, individualized nutritional therapy. Compared with standard hospital nutrition, nutritional therapy aimed at achieving protein and energy targets significantly reduced major complication (NNT=25) and mortality (NNT=37) rates (Figs. 2 and 3). In addition, functional impairment occurred significantly less frequently and quality of life improved significantly [8]. A recent meta-analysis that included these two studies concluded that adequate nutritional therapy in malnourished patients reduces the risk of both mortality and elective rehospitalizations by approximately 25% [5].

Nutrition Management

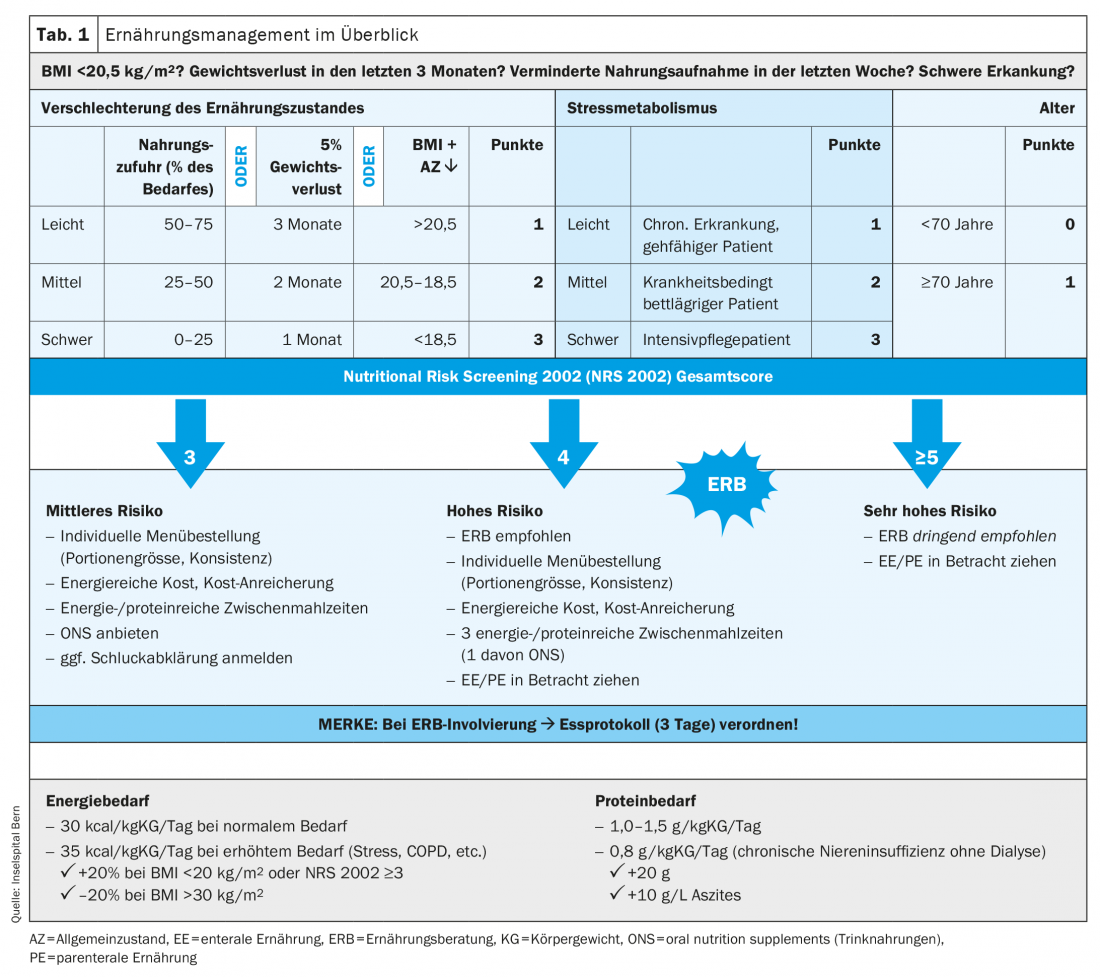

The goal of nutrition therapy is to maintain or improve nutritional status and quality of life through adequate administration of nutrients. To prevent deterioration of nutritional status, rapid and functional nutritional management is required (Tab. 1). In view of the increasing need for nutrition therapy in the outpatient setting – more elderly patients in need of care, polymorbid patients – it makes sense to develop a specialized field of care for nutrition therapy in close cooperation with an advanced practice nurse. The use of health professionals in advanced practice roles, particularly in nutrition management, is promising, in our opinion. They have in-depth clinical skills and act according to current scientific evidence. Thus, they can independently counsel, treat or accompany patients with complex medical conditions. This leads to efficient and sustainable development in nutrition therapy.

Screening and assessment in the outpatient setting: Standardized procedures are necessary to initiate timely and adequate nutrition therapy. Systematic screening for ME risk should be performed, followed by a comprehensive nutritional assessment, and lead to the development of a personalized nutrition plan. Screening to determine ME risk is the first step in identifying early, or at best preventing, deterioration in nutritional status. Screening should quickly and sensitively identify individuals who need nutritional assessment.

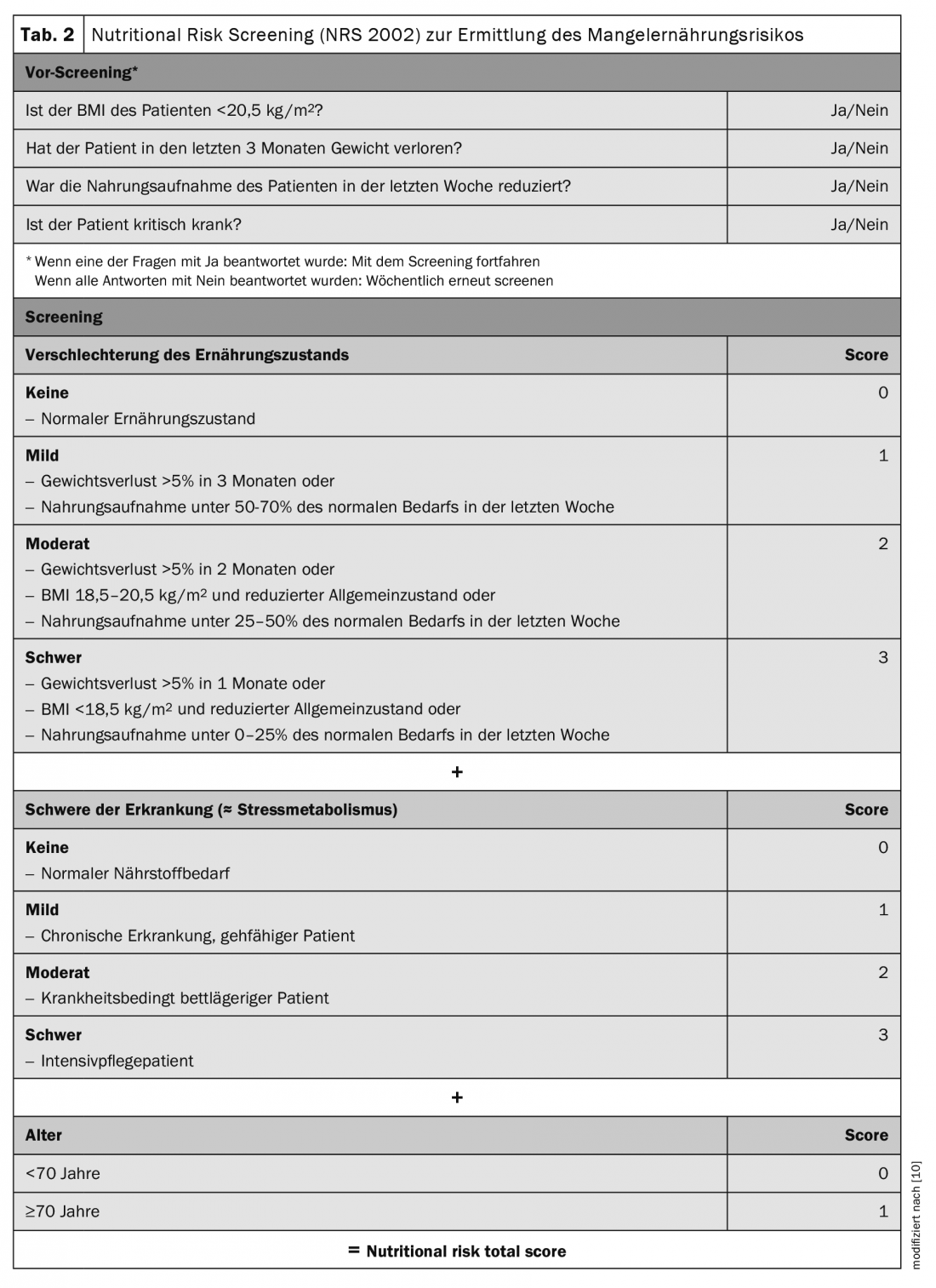

Screening should be performed with validated instruments. ESPEN recommends the Nutritional Risk Screening 2002 (NRS 2002, Tab. 2). It can be performed in a few minutes and is currently the best validated screening instrument [9,10]. It was developed in 2002 by Jens Kondrup’s group and is one of the most widely used in hospitals worldwide. It consists of a pre-screening with 4 questions. If a question is answered positively, the NRS 2002 screening must be performed. It considers assessment of nutritional status (0-3 points), disease severity (0-3 points), and age (1 point if ≥70years). Points are added to a total score, with ≥3points indicating ME risk or manifest ME, and nutritional assessment is indicated.

A nutrition assessment is a comprehensive approach to objectively evaluate nutritional status. It incorporates medical history, physical examinations, anthropometric measurements (weight, height, BMI), functional tests, quality of life, physical activity, and laboratory values. In practice, a simplified assessment can be performed based on weight, height, BMI and subjective parameters that correlate with nutritional status according to the literature, such as appetite, general well-being and performance. The easiest way to record subjective parameters is with a visual analog scale, similar to the recording of pain (scale 1-10).

Nutrition plan: In line with the development of personalized medicine, the nutrition plan is always adapted to individual needs. These needs are largely dependent on the nutritional status assessed in the assessment, with the underlying disease, weight history, appetite and current food intake being key factors. Problems such as mastication, odynophagia, dysphagia, xerostomia, dysgeusia, mucositis/soor, nausea/emesis, constipation/diarrhea, or pain also play a weighty role in the nutrition plan. Other aspects such as dietary habits, preferences/aversions, psychosocial situation, and physical activity must be considered. Conducting an eating log for 3-5 days is very useful to semiquantitatively record the amount of food consumed and to learn about eating habits in detail (for inpatients, the plate chart model can also be used). Prior to nutritional therapy, drug therapy should be optimized, e.g., fixed antiemesis, laxative measures, mouth rinse, saliva substitute, acid blocker, etc.

Energy, protein, and fluid requirements: Determining energy requirements is a key point of the nutrition assessment. Total energy expenditure is composed of resting energy expenditure, food-induced thermogenesis, and energy expended during physical activity. Total energy requirements can be calculated using an age-, sex-, and weight-specific formula that also takes into account activity and stress factors (e.g., Harris-Benedict formula [11]). In practice, it can be roughly estimated with a simplified weight-based formula as follows: 30-35 kcal/kg/day; plus 20% for an NRS 2002 ≥3or BMI <20 kg/m2; minus 20% for a BMI >30 kg/m2 [12]. A balanced whole food diet in malnourished patients should provide 40-60% of energy needs with carbohydrates, 10-20% with proteins, and 30-40% with fat.

The protein requirement for healthy individuals is generally 0.8 g/kg/day. In chronic renal failure, protein intake must be reduced to 0.6 g/kg/day unless dialysis is used. In elderly patients (>65 years) with chronic renal failure, protein intake is 0.8 g/kg/day. In the case of dialysis, the protein requirement is the same as in the normal case and there is an additional requirement of about 20 g of protein after dialysis (dialytic loss). Patients lose approximately 10 g of protein per liter of ascites during paracentesis [4]. For malnourished patients with acute or chronic illness, protein intake recommendations are 1.0-1.5 g/kg/day [13]. There are no specific recommendations for polymorbid patients with chronic renal failure. Our clinical experience indicates that this population requires approximately 1 g/kg/day [8]. An individual target must be defined for each patient, as other factors, such as hypermetabolism, may alter protein requirements (e.g., additional stressors such as underlying COPD or tumor disease).

In general, attention should be paid to sufficient and adequate fluid intake. The fluid regulation should (i) compensate for the imperceptible loss (500-1000 ml), (ii) Provide sufficient water and electrolytes, (iii) maintain the normal status of the body fluid compartments; and (iv) Provide sufficient water to allow the kidney to excrete waste products (500-1500 ml). The average requirement is 30-35 ml water/kg/day, 1 mmol sodium/kg/day and 1 mmol potassium/kg/day. The guideline for total water intake is >2 liters per day (about 1.1 ml of water per kcal), of which about 1.4 liters should be consumed in the form of beverages. In the case of special indications, drinking quantities deviating from this guideline value are possible and are determined by the physician [14]. The causes of fluid deficiency, or dehydration, are varied and are usually based on insufficient fluid intake combined with excessive fluid loss. Common etiologies include illnesses with diarrhea, vomiting, or fever (for each degree above 37°C, the body needs an additional 300 ml of fluid daily), the use of diuretics or laxatives, dysphagia, decreased thirst sensation, very hot outdoor temperatures, and physically demanding work or sports (additional requirement of 0.5-1.0 liters of water per hour of intense activity). Any fluid prescription should cover not only daily maintenance needs but also abnormal losses. In the case of losses from the gastrointestinal tract, such as from a fistula or nasogastric aspiration, the fluid prescription should include the daily maintenance requirement plus an equivalent replacement of water and electrolytes.

Micronutrient requirements: in malnourished polymorbid patients, micronutrient requirements may be increased due to reduced dietary intake or disease-related. Micronutrients should be supplemented and/or substituted according to the recommended daily dose. Daily micronutrient requirements are considered met when enteral tube feedings are at least 1500 mL per day. Vitamins and trace elements are not included in parenteral nutrient solutions and should be supplemented additionally [4].

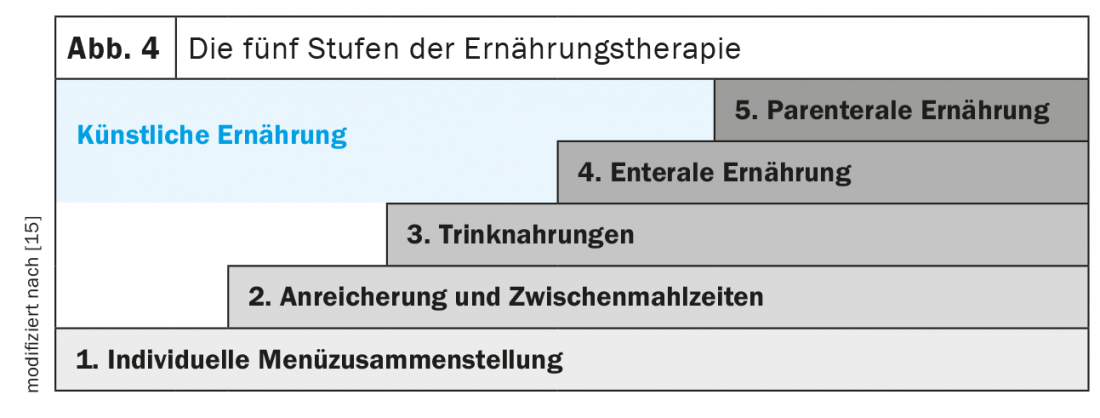

The five steps of nutrition therapy (Fig. 4) : The first step is to educate patients about energy- and protein-rich diets and meal rhythms (frequent meals throughout the day), address any problems that may be preventing adequate nutritional intake, and evaluate optimization measures. Oral nutrition with natural foods rich in energy and protein should be the first choice of nutritional therapy. It includes adjustments to food texture (temperature, taste, consistency, color), individual preferences, choice of low-odor foods, adapted portion size, and mild meal preparation and use of assistive devices (spoon, cup, teat, etc.). In addition, meals can be enriched with natural foods such as high-quality vegetable oil, butter, cream, cottage cheese, grated cheese, egg or with special products such as protein or carbohydrate powder (maltodrextrin). Additional energy-dense snacks (e.g. homemade milkshakes, canapés, crèmes) can be included in the daily schedule.

The next stage is the administration of commercial fully balanced sip foods, which can be served in an appealing and creative way. As early as 1990, the study by Delmi et al. demonstrate that evening administration of a fully balanced drinkable food (20 g protein, 254 kcal) increased energy intake by 23% and protein intake by 62% in geriatric patients with femoral neck fracture. This intervention significantly reduced complication rates, length of stay in hospitals and rehabilitation units, and mortality [16]. Further studies showed that complementary administration of sip feeds as a snack did not decrease appetite but significantly increased total energy and protein intake. Several studies and meta-analyses showed that sip feeds can preserve muscle mass and improve quality of life, and also lead to significant reductions in complication, mortality, and rehospitalization rates [7,8,17–21]. Overall, several studies, which are primarily based on retrospective cost analyses, suggest that the use of sip feeds in the outpatient setting provides an overall cost benefit. This is often associated with clinically relevant outcomes, indicating cost-effectiveness [22].

If oral nutrition is insufficient (<75% of energy and protein requirements) or not possible, enteral and, if appropriate, parenteral nutrition should be considered. Enteral nutrition is preferred in patients with a partially functioning gastrointestinal tract because of the lower risk of infectious and noninfectious complications. Both artificial invasive diets should be complementary and noncompetitive. If no special needs are present, it is recommended to start with a standard tube feed or nutrient solution. There is a wide selection of more specific products for both diets if needed.

Energy and protein intake should be assessed approximately 2-3 times a week for acutely ill patients, depending on available staff resources, and every two to four weeks for chronically ill patients in the primary care practice as part of a reassessment. Depending on the course, further nutritional goals and interventions should be defined and, if necessary, further therapeutic measures should be taken. Regular physician-patient contact and contact with dietitians or advanced practice nurses provide a good opportunity to review therapeutic recommendations and improve their implementation.

Nutrition for specific disease states: In patients with renal insufficiency, potassium and phosphate intakes often need to be restricted. Patients with heart failure may benefit from sodium and water restriction or regular thiamine and iron supplementation in certain cases. There is weak evidence to support the use of specific oral nutritional supplements or enteral nutritional solutions in polymorbid hospitalized patients. Arginine, glutamine, and beta-hydroxy beta-metylbutyrate (HMB) can be used in patients with pressure ulcers. A mixture of soluble and insoluble fibers can be used in chronically ill patients who are fed enteral nutrition and suffer from diarrhea or constipation, the most common complications of enteral nutrition. Special attention should be paid to hydration status, as dehydration can lead to constipation [4].

Timing of nutritional therapy: early initiation of nutritional therapy (in hospital within 48 hours of admission) is recommended to prevent deterioration of nutritional and functional status and sarcopenia. Although the optimal duration of nutritional therapy is still unclear, current evidence recommends treatment beyond hospital discharge [13].

Monitoring of nutrition therapy: experienced clinical nutrition teams (in inpatient settings) and dietitians or advanced practice nurses (in outpatient settings) should review the indication, route of administration, risks, benefits, and goals of nutrition therapy at regular intervals. The duration of this interval depends on the patient and the parameters being monitored (e.g., nutritional, anthropometric, biochemical parameters, clinical condition) and may be prolonged if the patient’s condition improves with nutritional therapy. For example, it is recommended that nutrient intake by oral, enteral, or parenteral nutrition be monitored daily initially in the inpatient setting or when artificial therapy is initiated, and twice weekly when the condition is stable (e.g., when there is a high risk of developing refeeding syndrome). Similarly, laboratory parameters (e.g., potassium, magnesium, phosphate, sodium, urea, creatinine) should be monitored daily at the beginning, and later 1-2 times per week. In addition to parameters used to monitor response to nutrition therapy, functional indices (e.g., fist closure strength) should be collected regularly to assess other clinical outcomes (e.g., survival, quality of life) [4]. The intervals between follow-up visits in the outpatient sector are significantly longer than in the inpatient sector.

Raising awareness on the prevention, identification and treatment of malnutrition.

ME should be addressed more frequently in the education and training of medical staff in both hospital and outpatient settings. Awareness of ME needs to be increased and nutrition management needs to be seen as part of medical multimodal treatment. ME is still too often not identified, under-diagnosed and consequently not treated.

Clearly defined protocols and responsibilities are needed to address this issue in both the inpatient (at hospital admission) and outpatient (at initial/follow-up consultations) settings. This begins with the introduction of systematic nutrition screening, followed by rapid and simple nutrition assessment in at-risk patients. A recent study showed that about 80% of hospitals and nursing homes in Switzerland have not implemented a systematic screening process for ME risk and that only 25% of hospitals screen patients when they suspect a problem. In addition, 56% of facilities monitor food intake and 50% monitor and document the nutritional status of their patients [23].

Since the etiology of ME is often multifactorial (ranging from depression to loss of appetite to inability to feed oneself), optimal communication and collaboration should be ensured between the inpatient treatment team, the outpatient treatment team/network (primary care physician, Spitex, home care, nutrition counseling, etc.), and the patient. This allows potential problems to be addressed efficiently and effectively.

ME is also a common problem in the outpatient setting. The role of primary care physicians and advanced practice nurses, resident specialists, dietitians, and nurse practitioners is essential to detect the signs of ME early (NRS 2002 prescreening/screening) and treat adequately accordingly. Nutrition therapy is usually started during hospitalization and continued in the outpatient setting and reviewed regularly. Based on many years of clinical experience and the findings of the EFFORT study, the follow-up study “Effect of Nutritional Therapy on Frailty, Functional Outcomes and Recovery of Undernourished Medical Patients at Discharge Trial” (EFFORT II) is now being planned in the outpatient setting – a Swiss investigator-initiated, non-commercial multicenter randomized controlled trial, which will start in the second half of 2021. The overall objective of this study is to demonstrate the persistent benefit of individualized home nutrition therapy in terms of mortality, major complications, nonelective rehospitalizations, and functionality according to an implementation algorithm over usual nutrition in polymorbid malnourished patients.

Conclusion

Appropriate, individualized nutritional therapy has been shown to be a very effective treatment option in the prevention and therapy of ME. It significantly reduces morbidity and mortality rates. It also significantly improves the quality of life and physical functionality. In view of the complexity of ME and in order to achieve long-term treatment success of nutritional interventions, additional measures such as physical activity and regular psychological support should be integrated in the sense of a multimodal therapeutic approach. During regular patient contacts, nutritional problems should be asked about and simple anthropometric data collected. It is important to incorporate the new knowledge brought to your attention in this review into clinical practice to ensure that patients receive optimal, high-quality, and safe care.

Take-Home Messages

- Malnutrition is common and associated with increased morbidity and mortality.

- It is critical to identify malnourished patients early with a simple screening tool (NRS 2002).

- Nutritional therapy must be planned, implemented, monitored and regularly adjusted.

- Targeted and adequate nutritional interventions are efficient and reduce complication and mortality rates.

- A functioning nutrition management is goal-oriented and ensures a high quality of treatment.

Literature:

- de van der Schueren MAE, Soeters PB, Reijven PLM, et al: Diagnosis of malnutrition – Screening and Assessment. In: Sobotka L, Allison SP, Forbes A, Meier RF, Schneider SM, Soeters PB, et al: Basics in Clinical Nutrition. 5 ed. Prague: Galén 2019; 18-27.

- Schindlegger W: Causes of anorexia in old age. Journal of Nutritional Medicine (Issue for Switzerland) 2001; 3(3): 20-23.

- Guigoz Y: The Mini Nutritional Assessment (MNA) review of the literature – What does it tell us? The journal of nutrition, health & aging 2006; 10(6): 466-485; discussion 85-87.

- Reber E, Gomes F, Bally L, et al: Nutritional Management of Medical Inpatients. Journal of clinical medicine 2019; 8(8).

- Gomes F, Baumgartner A, Bounoure L, et al: Association of Nutritional Support With Clinical Outcomes Among Medical Inpatients Who Are Malnourished or at Nutritional Risk: An Updated Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. JAMA network open 2019; 2(11): e1915138.

- Estruch R, Ros E, Salas-Salvado J, et al: Primary Prevention of Cardiovascular Disease with a Mediterranean Diet Supplemented with Extra-Virgin Olive Oil or Nuts. The New England journal of medicine 2018; 378(25): e34.

- Deutz NE, Matheson EM, Matarese LE, et al: Readmission and mortality in malnourished, older, hospitalized adults treated with a specialized oral nutritional supplement: A randomized clinical trial. Clinical nutrition 2016; 35(1): 18-26.

- Schuetz P, Fehr R, Baechli V, et al: Individualized nutritional support in medical inpatients at nutritional risk: a randomized clinical trial. Lancet 2019; 393(1088): 2312-2321.

- Kondrup J, Allison SP, Elia M, et al: ESPEN guidelines for nutrition screening 2002. Clinical nutrition 2003; 22(4): 415-421.

- Kondrup J, Rasmussen HH, Hamberg O, Stanga Z: Nutritional risk screening (NRS 2002): a new method based on an analysis of controlled clinical trials. Clinical nutrition 2003; 22(3): 321-336.

- Harris JA, Benedict FG: A biometric study of human basal metabolism. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 1918; 4(12): 370-373.

- Reber E, Strahm R, Bally L, et al: Efficacy and Efficiency of Nutritional Support Teams. Journal of clinical medicine 2019; 8(9).

- Gomes F, Schuetz P, Bounoure L, et al: ESPEN guidelines on nutritional support for polymorbid internal medicine patients. Clinical nutrition 2018; 37(1): 336-353.

- Padhi S, Bullock I, Li L, Stroud M: Intravenous fluid therapy for adults in hospital: summary of NICE guidance. BMJ 2013; 347: f7073.

- Aubry E, Mareschal J, Gschweitl M, et al: Facts about clinical nutrition management-an online survey. Current Nutritional Medicine 2018; 42(06): 452-460.

- Delmi M, Rapin CH, Bengoa JM, et al: Dietary supplementation in elderly patients with fractured neck of the femur. Lancet 1990; 335(8696): 1013-1016.

- Norman K, Pirlich M, Smoliner C, et al: Cost-effectiveness of a 3-month intervention with oral nutritional supplements in disease-related malnutrition: a randomised controlled pilot study. European journal of clinical nutrition 2011; 65(6): 735-742.

- Stratton RJ, Elia M: A review of reviews: A new look at the evidence for oral nutritional supplements in clinical practice. Clinical nutrition 2007; 2(1): 5-23.

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Nutrition support for adults: oral nutrition support, enteral tube feeding and parenteral nutrition (CG32)2006; last updated 2017.

- Chew STH, Tan NC, Cheong M, et al: Impact of specialized oral nutritional supplement on clinical, nutritional, and functional outcomes: A randomized, placebo-controlled trial in community-dwelling older adults at risk of malnutrition. Clinical nutrition 2020.

- Milne AC, Avenell A, Potter J: Meta-analysis: protein and energy supplementation in older people. Annals of internal medicine 2006; 144(1): 37-48.

- Elia M, Normand C, Laviano A, Norman K: A systematic review of the cost and cost effectiveness of using standard oral nutritional supplements in community and care home settings. Clinical nutrition 2016; 35(1): 125-137.

HAUSARZT PRAXIS 2021; 16(4): 11-17