Falls are a taboo for the elderly. The family doctor in particular should therefore actively inquire about them and determine the future risk. This is already possible with simple measures in practice.

Falls in old age are common and represent a drastic event for those affected and their relatives. Many falls lead to injuries, most feared are femoral neck fractures or even brain hemorrhages under anticoagulation. Many single seniors suffer recumbent trauma with all its complications or are afraid of further falls after the fall. They withdraw, move less, lose muscle strength and bone substance, and fall again.

Mortality is high, nursing home admissions often result, and quality of life usually falls by the wayside. Many patients do not self-report their falls for fear of nursing home admission. Therefore, it is especially important for the primary care physician to actively ask about falls, minimize fall causes and risk factors, and motivate the patient for fall prevention.

Causes of falls and risk factors

Most falls in the elderly are multifactorial, so it is important to evaluate and favorably influence as many of the causes and risk factors as possible. Falls in old age occur most frequently as so-called accidents of daily living (31%), followed by balance and gait disorders (17%), dizziness (13%), “drop attacks” (9%), and orthostatic dysregulation (3%). Actual syncope is rather rare (0.3%), although a high number of unreported cases probably remains. Sometimes only a banal urinary tract infection is the cause of a fall, or not infrequently the inner struggle with the imminent entry into a nursing home.

At home, most patients fall during the day while doing “housework” and in the hospital during the first week of hospitalization, usually while transferring or going to the toilet. In old age and especially in cognitive decline, the so-called “dual tasking” is disturbed, so that the patient can concentrate either on walking or on controlling the bladder.

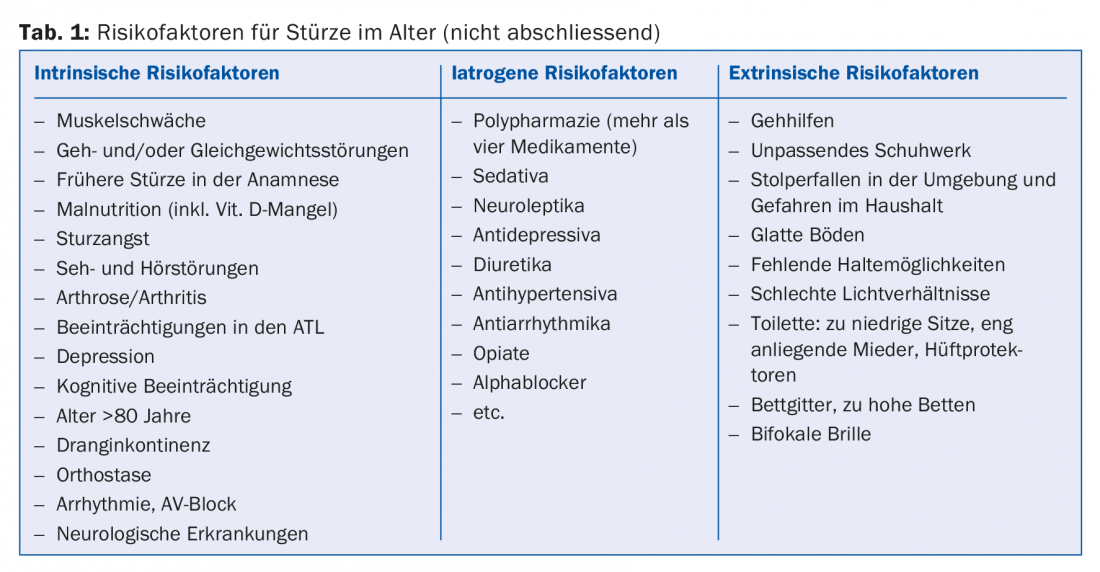

Table 1 shows the most common risk factors, here the increasing muscle weakness, gait disturbances and balance disorders are in the foreground. As the number of risk factors cumulates, so does the risk of falling, increasing from 27% with one cause of falling to as high as 72% with four or more risk factors.

Medication and fall risk

If more than four medications are taken, the risk of falling increases significantly, regardless of the substance class. But single substances also significantly increase the risk, especially drugs with an effect on the central nervous system (sleeping pills, antidepressants, antipsychotics), antihypertensives, opiates and alpha blockers. In this context, it is debated whether the drug or the underlying disease increases the risk of falls in each case.

Simple fall risk assessment at the family doctor (fall screening)

As part of an annual examination, the risk of falls in patients over 65-70 years of age should be addressed and determined. Here are a few simple and quick measures that can also be performed by an MPA. For example, handing out a brochure from the Swiss Council for Accident Prevention (bfu-Beratungsstelle für Unfallverhütung) (www.bfu.ch/de/fuer-fachpersonen/sturzprävention) to the patient could already draw attention to the topic (e.g., living space clarification checklist, or simple exercises to do at home). After the BP measurement in the sitting position, another BP measurement should be taken after standing up in order to detect any orthostasis and to take it into account in the BP setting.

The “Stop walking while talking” test is quick and easy to perform: You accompany the patient for a while and engage him or her in conversation. If the patient stops to respond, “dual tasking” is limited and the patient is at risk of falling. Simple assessment tests such as the one-leg and tandem stance tests (balance) or the timed-up-and-go test (strength and walking speed) can also detect an increased risk of falling. In addition, patients’ medications should generally be reviewed and adjusted if necessary. It would be desirable to minimize other fall risk factors. If desired, comprehensive outpatient fall assessment can now be delegated to many geriatric clinics or geriatric outpatient clinics.

Diagnostics after fall

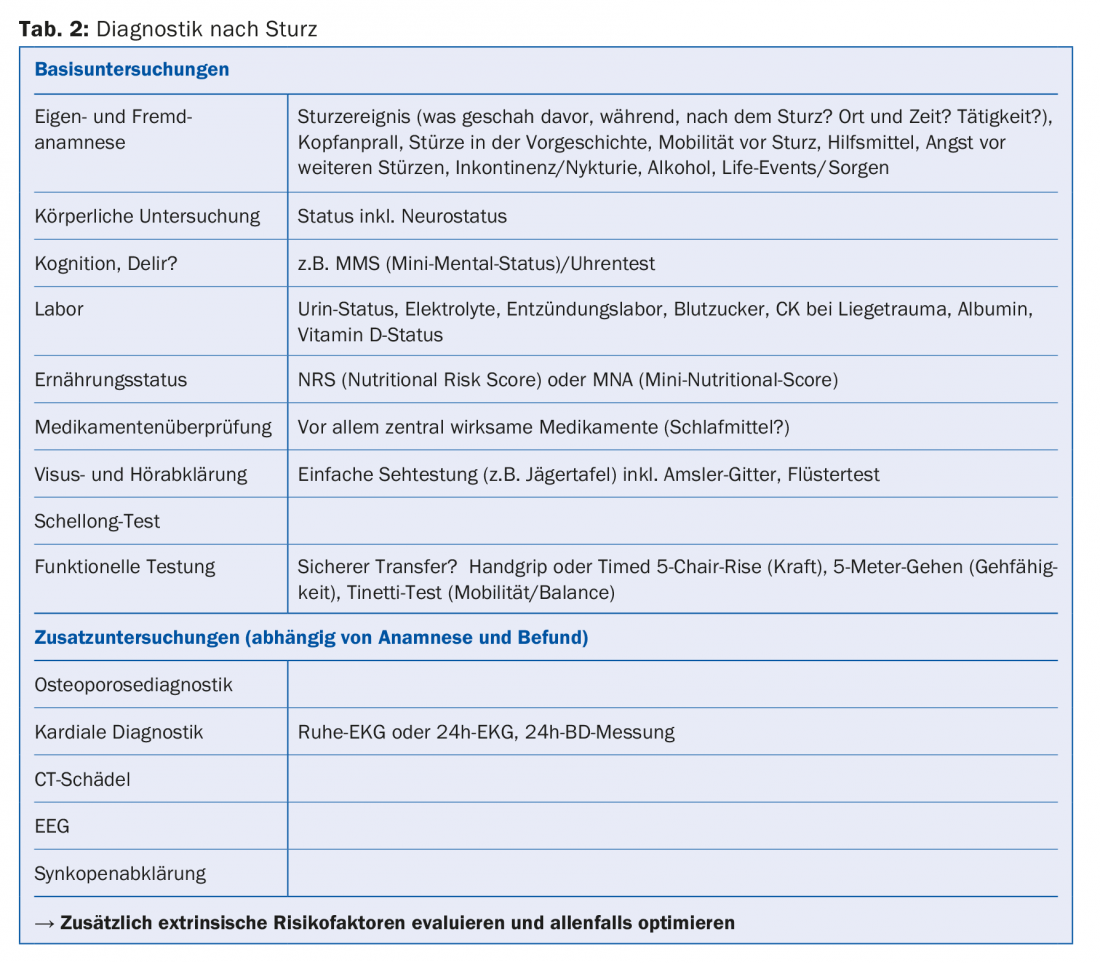

Medical history (self and others), physical examination, simple laboratory tests and functional tests can already often reveal the causes and risk factors of falls. The cause of the fall often cannot be determined accurately due to cognitive impairment or difficult history taking for various reasons. It is important to note that even a banal “trip and fall” is usually based on several risk factors and it is necessary to record these and take them into account for secondary prevention. Table 2 shows a possible approach to falls.

“Fear of falls”

Post-fall syndrome or “fear of falls” is associated with a significantly longer hospitalization and rehabilitation period, as well as a severe reduction in independence and quality of life. It is common in the elderly, especially in patients with recumbency trauma, history of falls, and cognitive impairment. Patients are very anxious and report increased pain, can only be mobilized with great difficulty and with the help of experienced nurses or therapists, and grasp for any support they can get. The syndrome is difficult to treat and, above all, needs a lot of time. Patients need intensive physiotherapy without under- or overstraining, sometimes psychological supportive talks and sometimes anti-anxiety antidepressants.

Atrial fibrillation and falls

Anticoagulation should generally be well considered in the very elderly. Nevertheless, this is often necessary because of thromboembolic events that have taken place or in permanent or intermittent VHF with a CHA2DS2-VASc score ≥2. Often the elderly are underserved here for fear of a bleeding complication, especially affecting patients with recurrent falls. An extrapolative analysis showed that patients would have to fall nearly 300 times per year for the risk of major bleeding to outweigh the benefit. Recent studies show a good efficiency-risk ratio especially for NOACs and particularly for edoxaban. Treatment with aspirin for atrial fibrillation shows no beneficial effect and is not recommended.

Therapy and fall prevention

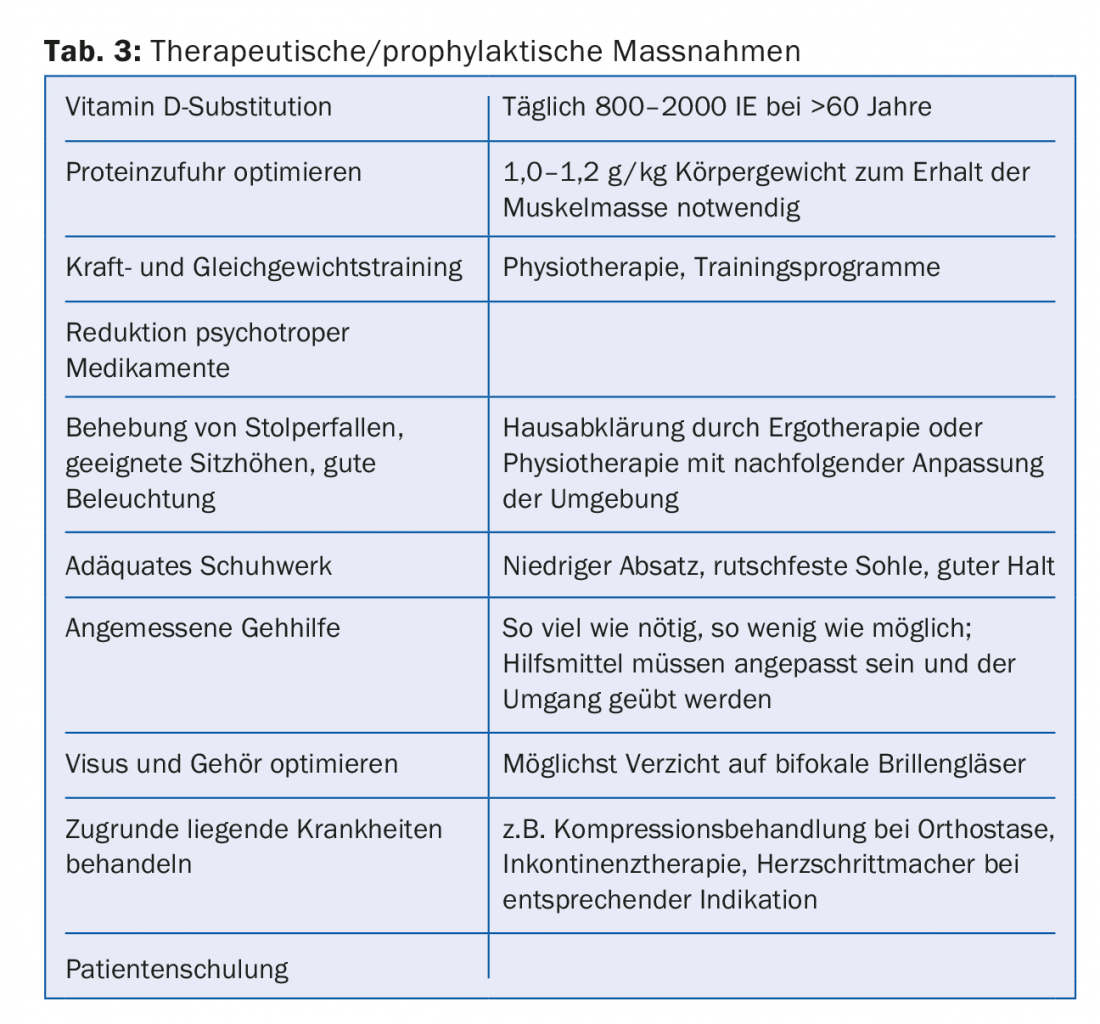

Diagnosis, therapy and prophylaxis cannot be clearly distinguished from one another in the case of falls in old age and overlap in terms of content. Also, the primary and secondary prophylactic measures are almost identical. The most important therapeutic and prophylactic measures are summarized in Table 3 . Prophylactic measures can reduce the rate of falls, but falls can ultimately never be completely prevented. In some cases, the rate of falls even increases again when previously immobile people become more mobile again through targeted training. The goal here is to achieve a good quality of life with the greatest possible autonomy for patients. In most cases, freedom (without measures restricting freedom) comes before safety for patients, which can lead to conflicts in the family, as relatives often worry. This situation also often leads to uncertainty and anxiety in care teams.

It is therefore important to minimize (to a certain extent) both the rates of falls and, above all, the consequences of falls through targeted measures.

Take-Home Messages

- Falls are a taboo subject for elderly people and should therefore be actively inquired about.

- A fall risk assessment should be performed at least annually to identify risk factors and initiate prophylactic measures.

- Falls are usually multifactorial and even “pure tripping falls” should be further investigated.

- Targeted measures reduce the rate of falls, minimize the consequences of falls and help improve patients’ quality of life.

- Falls are not a contraindication to OAK.

Further reading:

- Heinimann NB, et al: Falls in the elderly. Praxis 2014; 103(13): 767-773.

- Münzer T, et al: Assessment of fall risk and fall prevention in family practice. Schweiz Med Forum 2014; 14(46): 857-861.

- Rubenstein LZ, et al: Detection and management of falls and instability in vulnerable elders by community physicians. JAGS 2004; 52: 1527-1531.

- Rubenstein LZ: Falls in older people: epidemiology, risk factors and strategies for prevention. Ageing 2006; 35(Suppl 2): 37-41.

- Rapp K, et al: Epidemiology of falls in residential aged care: analysis of more than 70000 falls from residents of bavarian nursing homes. J Am Med Dir Assoc 2012; 13(2): 187.e1-6.

- Lundin-Olsson L, et al: “Stops walking when talking” as a predictor of falls in elderly people. Lancet 1997; 349: 617.

- Breitenstein A, et al: Atrial fibrillation and anticoagulation update 2016. Cardiovascular Medicine 2017; 20(1): 3-8.

- Leipzig RM, et al: Drugs and falls in older people: a systematic review and meta-analysis: I. Psychotropic drugs. J Am Geriatr Soc 1999; 47: 30-39.

HAUSARZT PRAXIS 2018; 13(3): 18-21