With the widespread use of ultrasound equipment and the performance of computed tomographic cross-sectional imaging, kidney stones are detected more frequently nowadays than in the past. The goal of imaging procedures is to quickly confirm the diagnosis in order to initiate the necessary therapy.

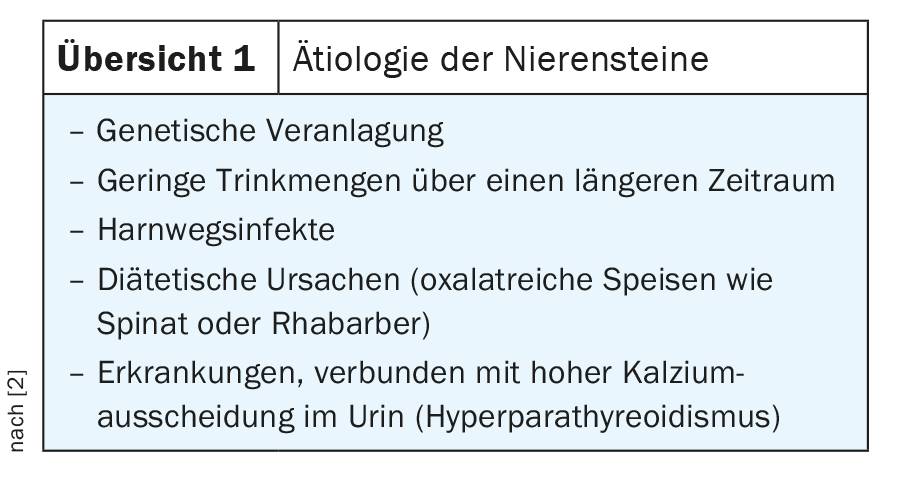

Nephrolithiasis, the presence of calculi in the kidneys, is a form of urolithiasis [2,3]. Various causes can lead to the formation of kidney stones, as shown in overview 1. The incidence is about 0.5% per year in Europe and the United States of America, and the lifetime risk of disease is about 10-15%. The frequency of recurrence is around 50%, but 10-20% of stone carriers have a frequency of 3 or more recurrences. However, over a long period of time, nephrolithiasis may be clinically silent. Familial clustering occurs, and the disease ratio of males to females is 4:1.

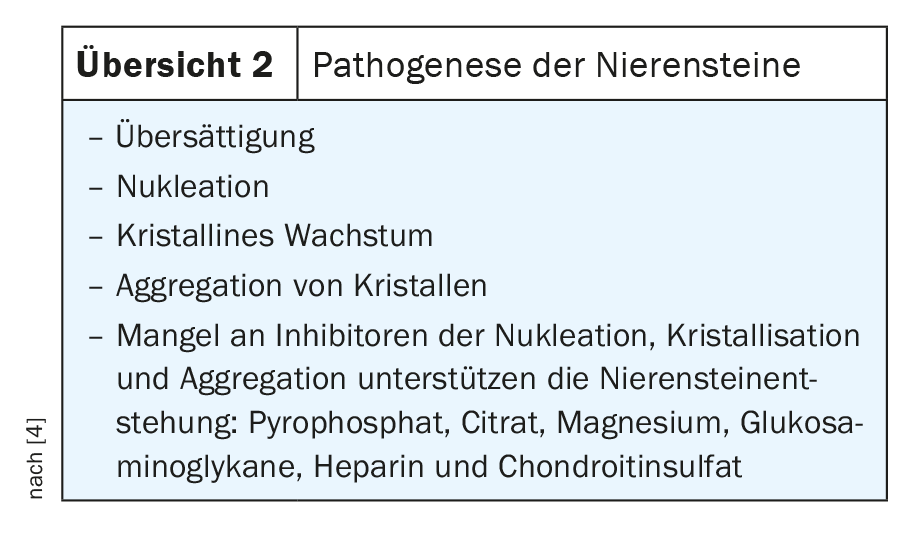

80% of urinary calculi are calcified and therefore readily visible on native CT. Biochemically, different calcium-containing stones can be distinguished. The formal pathogenesis of renal stones recognizes several mechanisms [4], listed in review 2 . Common clinical findings and laboratory data include pollakiuria, hematuria, and leukocyturia [1]. Stone passage often causes colicky pain, a strong urge to urinate, and hematuria.

Therapeutically, nephroliths can be removed endoscopically or disrupted by extracorporeal shock wave lithotrypsy. The recurrence rate can be reduced by urinary alkalinization with medication; adequate drinking quantities are also very important.

Radiographic examinations are of secondary importance in the detection of nephrolithiasis. The native survey radiograph of the abdomen may show calcifications suspicious for concretion, but the findings are uncertain when superimposed on stool-filled bowel portions. The i.v. urography, which was often requested in the past, has lost considerable importance.

Sonography is the method of choice for stone detection and is a widely used and inexpensive examination procedure. As a rule, the kidneys can be well adjusted, assessed and concretions can be detected in most cases with a size from 2 to 3 mm. The stones are echo rich and cause a sound shadow [3]. Any buildup is detectable.

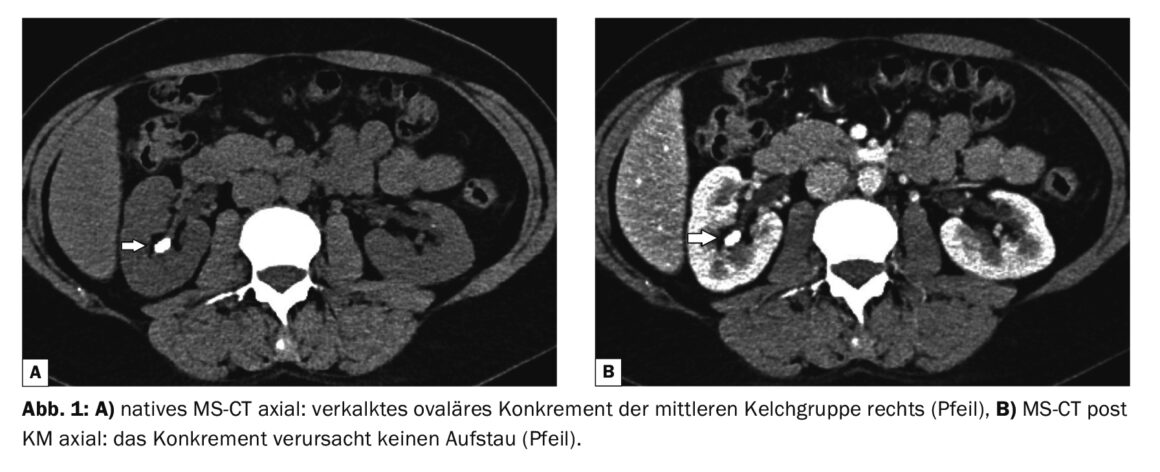

Computed tomography can natively (“stone CT”) reliably detect the calcified concretions in the renal cavity system and the draining urinary tract. Perfusion defects can be visualized in the contrast scans and, with late images in the CT urogram, outflow conditions can be visualized with coronal reconstruction. Papillary calcifications and arterial vascular calcifications must be differentiated from renal stones [5].

Magnetic resonance imaging has deficiencies in detecting small calcified calculi, and the small calcified nephroliths may escape detection in the absence of signal. In the contrast sequences, renal function can be visualized and urographic images can also be reconstructed as in CT.

Case studies

In case report 1, computed tomographic evidence of nephrolithiasis has been obtained. The 42-year-old female patient complained of recurrent right flank pain. A functional disorder could be excluded (Fig. 1A and 1B).

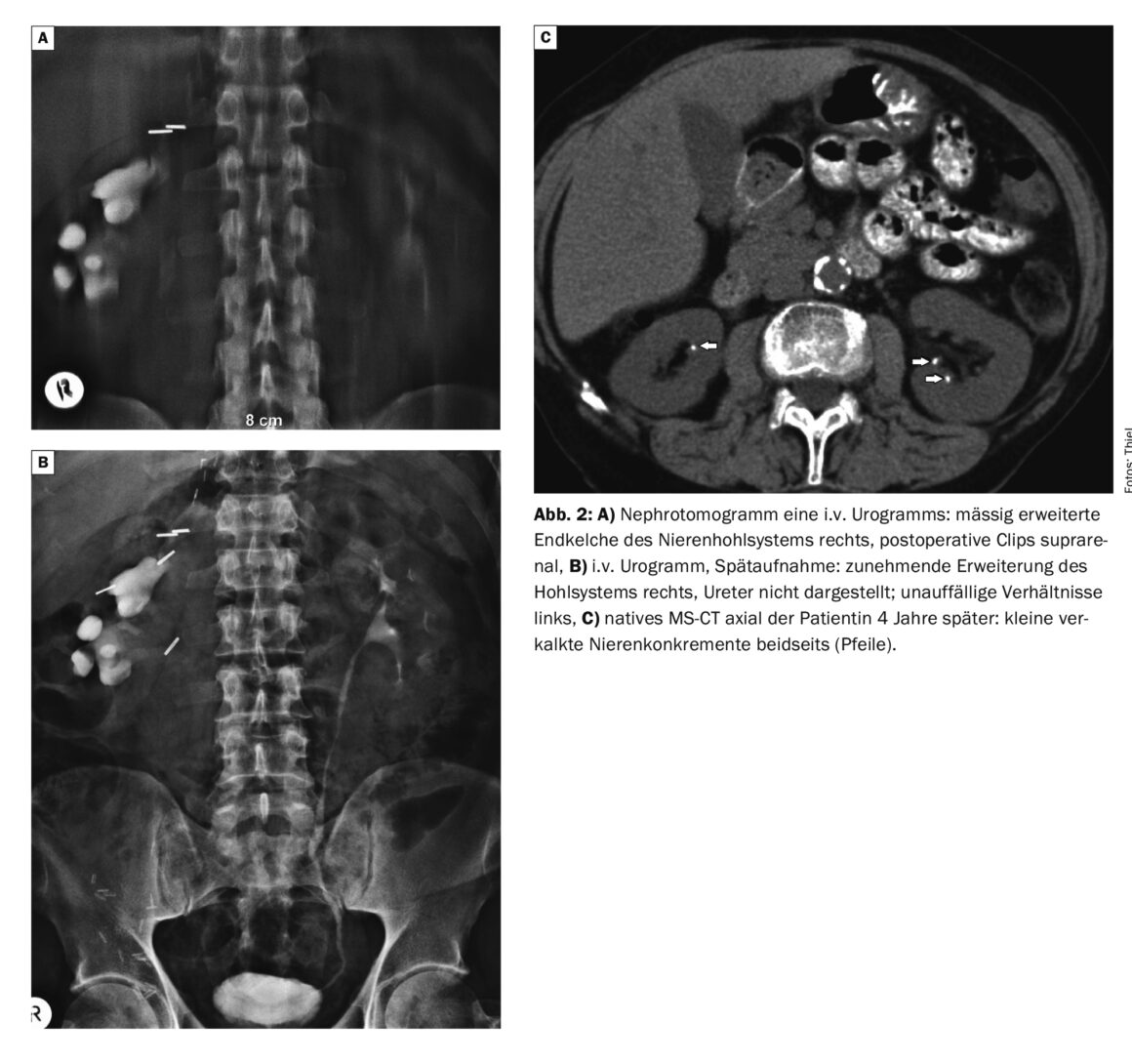

Case 2 shows images of an i.v. urogram with tomogram in a then 79-year-old female patient, hardly common today. Z.n. adrenocortical carcinoma, numerous suprarenal clips. A moderate dilatation of the terminal calyces on the right side with unremarkable findings of the left kidney was conspicuous. Four years later, recurrent bilateral flank pain on CT showed small calcified kidney stones in both kidneys (Figs. 2A to 2C).

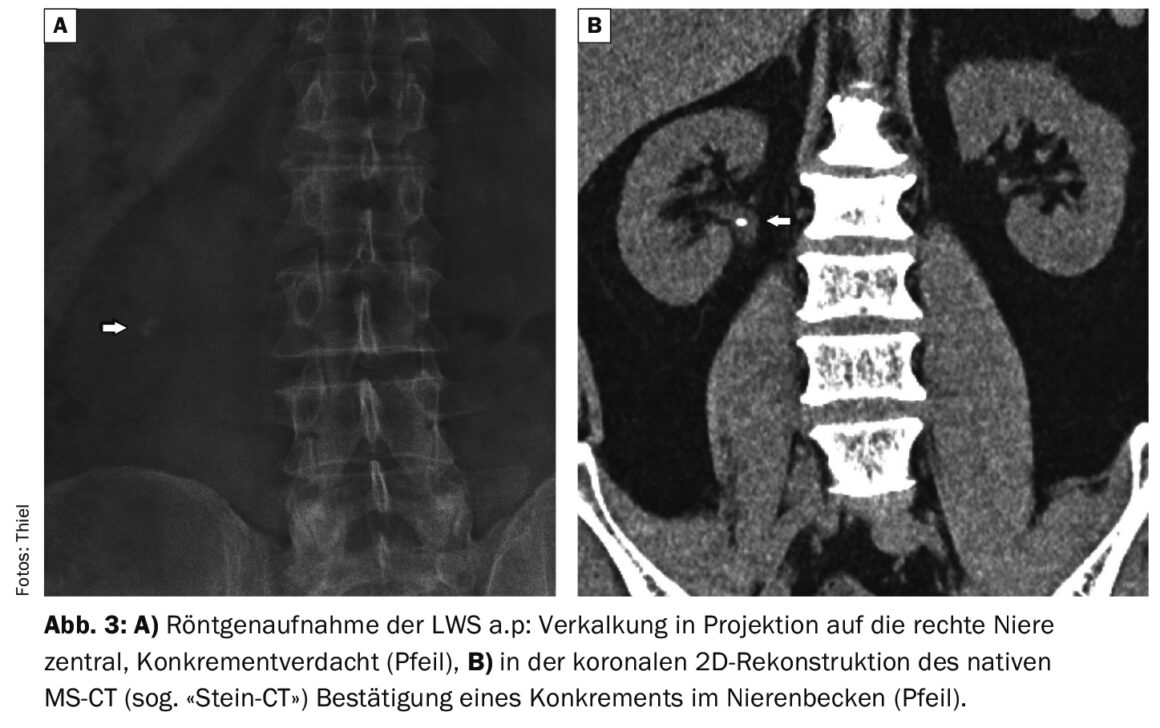

In case report 3, an X-ray examination of the lumbar spine in a 52-year-old patient had raised the suspicion of a renal calculus on the right side. Three months prior to the imaging, surgery was performed for a right inguinal hernia, and now there was pulling abdominal pain on the right side. CT confirmed the finding of a renal pelvic stone (Figs. 3A and 3B).

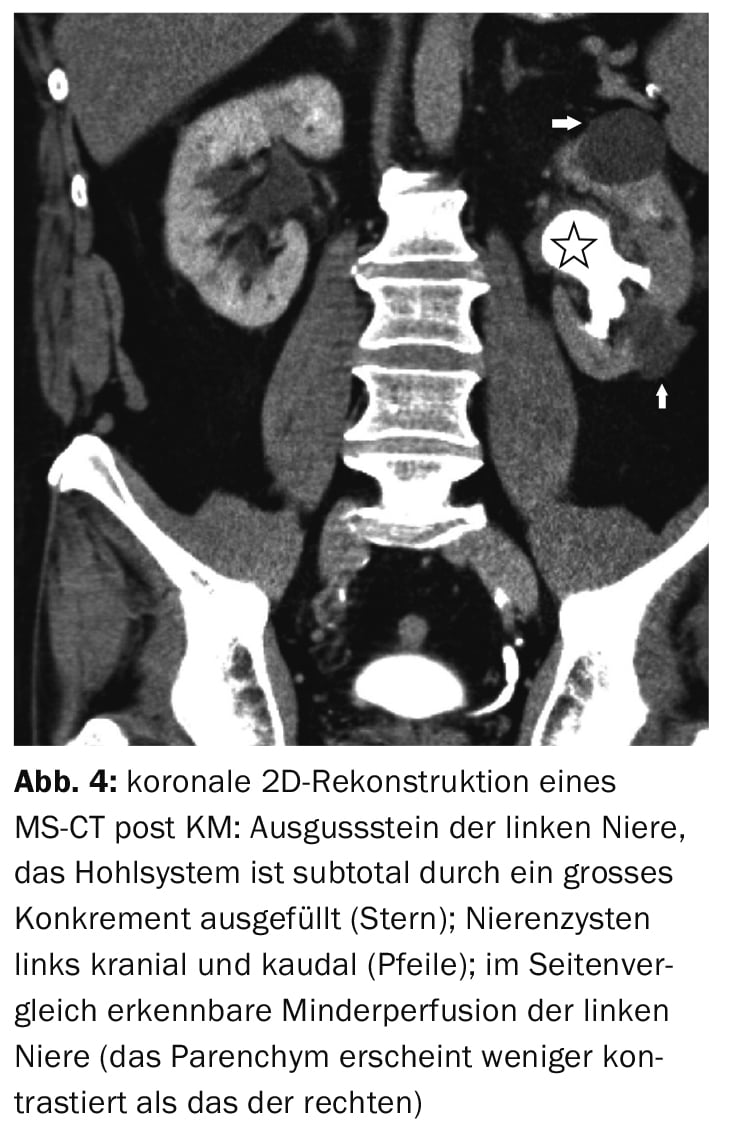

Case example 4 demonstrates the extreme form of nephrolithiasis, a left kidney spill in the presence of abdominal pain on that side (Fig. 4).

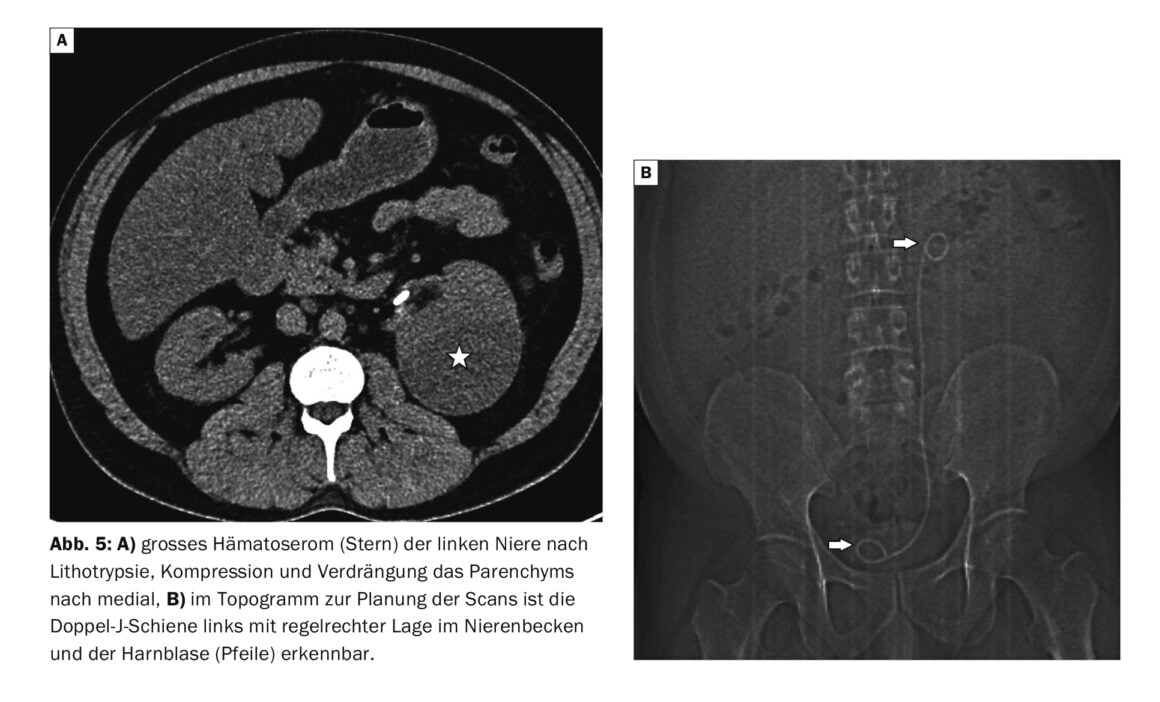

Case report 5 documents a pronounced hematoseroma of the left kidney laterally with compression of the renal pelvis as a complication of a lithotrypsia that had occurred. The inserted double J catheter can be seen in the topogram throughout the course (Fig. 5A and 5B).

Take-Home Messages

- Kidney stones can be solitary or multiple.

- Symptomatology is variable, ranging from asymptomatic to significant colic.

- Incarcerated or occluding ureteral stones occasionally cause complications with hydronephrosis or abscesses; permanent loss of function of the affected kidney is rare today.

- Sonography is the primary investigative procedure for suspected

for kidney stones, native computed tomography can provide concretion detection down to the urinary bladder, and with contrast scans can also provide functional assessment.

Literature:

- Dietel M, Suttorp N, Zeitz M (eds.): Harrison’s Internal Medicine. Volume 1; 17th ed. ABW Wissenschaftsverlag Berlin 2008; 337.

- Nephrolithiasis, https://flexikon.doccheck.com/de,(last accessed Mar 14, 2023).

- Urolithiasis, www.amboss.com/de/wissen,(last accessed Mar 14, 2023).

- Nephrolithiasis, www.urologielehrbuch.de,(last accessed Mar 14, 2023).

- Prokop M, Galanski M (Eds.): Spiral and Multislice Computed Tomography of the Body. Georg Thieme Verlag Stuttgart, New York 2003; 654.

HAUSARZT PRAXIS 2023; 18(5): 25-27