Inhaled tobacco smoking remains the most important preventable risk factor for numerous diseases and for premature deaths worldwide. In Switzerland, more than 1.9 million people smoked in 2017, representing 27% of people over the age of 15. 56% of smokers were between 15 and 44 years old in 2017. Stopping smoking as early as possible in the lives of smokers is the most important measure to prevent disease and death.

Inhaled tobacco smoking remains the most important preventable risk factor for numerous diseases and for premature deaths worldwide. 50% of smokers die prematurely, on average 14 years earlier [1]. In Switzerland, more than 1.9 million people smoked in 2017, representing 27% of people over the age of 15. 56% of smokers in Switzerland were aged 15-44 years in 2017 [2]. Smoking rates in the EU show a wide variance from 7% in Sweden to 42% in Greece [3], with an average EU smoking rate of 26%. In Germany, the number of smokers has increased again over the last 3 years and currently stands at 35.5% [4].

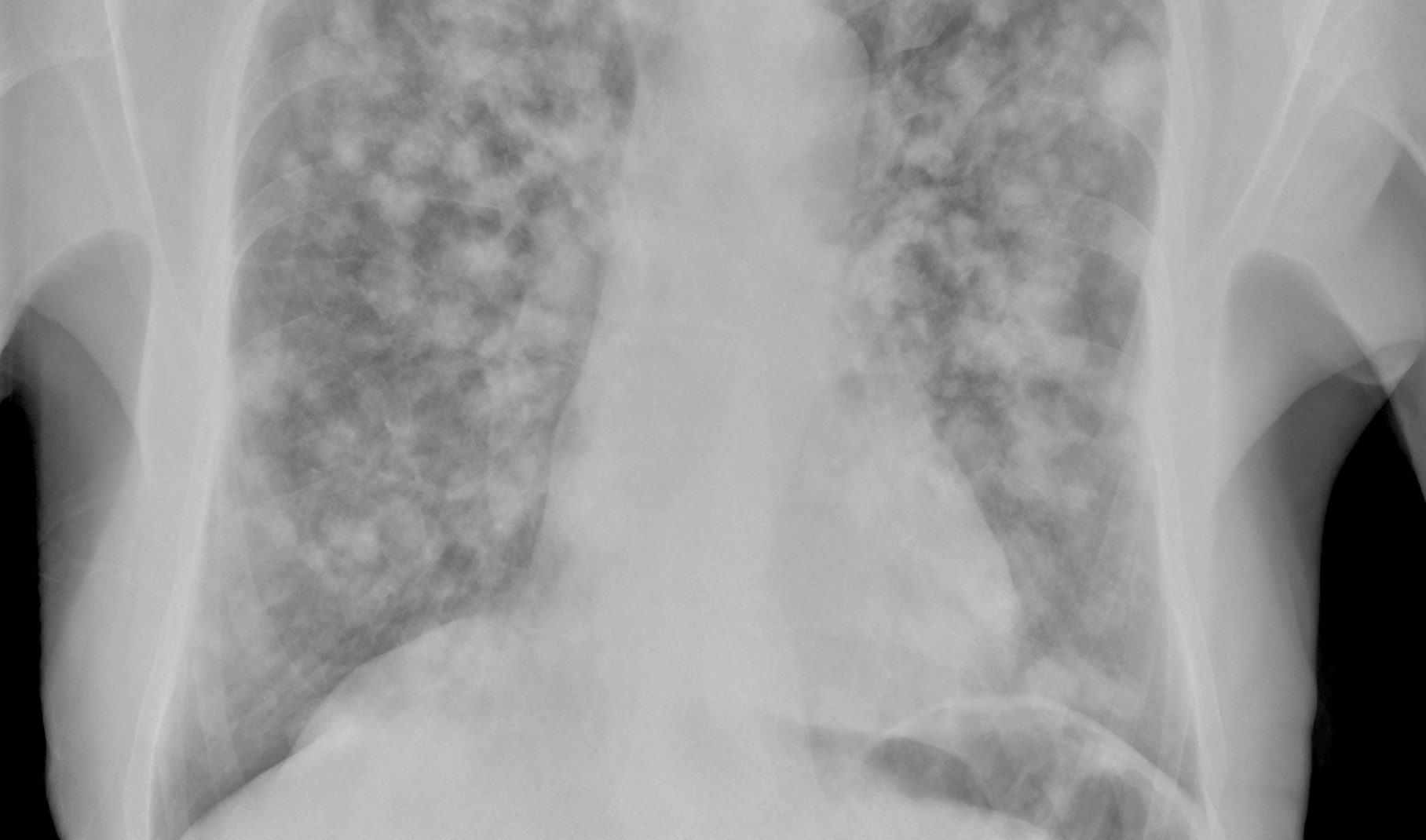

The annual direct and indirect socioeconomic costs caused by tobacco consumption are estimated at nearly 4 billion Swiss francs for Switzerland [5] and about €97 billion for Germany [6]. Tobacco smoking is responsible for approximately 9500 tobacco smoke-associated deaths in Switzerland (14% of all deaths) [5] and 127,000 in Germany [7]. It is estimated that 700,000 smoking-related deaths occur annually in the EU [1]. Cardiovascular disease, lung disease, and cancer account for the majority of smoking-related deaths [8].

Stopping smoking as early as possible in the lives of smokers is the most important measure to prevent disease and death. One in five smokers attempts to quit smoking each year in Germany, but usually without evidence-based support [9]. Only in 13% of smoking cessation attempts, one of the evidence-based methods is used in the smoking cessation attempt and only in 2% of cases the gold standard, i.e., the combination of behavioral therapy and medication support [9]. Non-assisted smoking cessation attempts show success rates of only 3-7% [10] whereas the gold standard can achieve long-term success rates of 30-35% [11], sometimes 45% [12].

An “ideal” care structure holds various support services for smokers, as exemplified in Figure 1. Services range from simple medical advice to more intensive counseling, group training, and intensive individual or group therapy. Financial reimbursement of support services is to be demanded, but in Germany it has so far only been implemented in individual projects such as the selective contract for pneumology in Baden-Württemberg [13] and not on a regular basis. Minimal interventions such as the “5A-” and the “ABC-rule” offer a well-remembered guide for clinicians and practitioners to implement in everyday life (Tab. 1) .

In addition to the habit and rituals of smoking, tobacco dependence is an important barrier to quitting. It is estimated that 50-60% of smokers have tobacco dependence [14], which in many cases leads to withdrawal symptoms such as irritability, irritability, nervousness, difficulty concentrating or sleeping, and a strong desire to smoke (craving) as part of the reduction or cessation process.

Drug therapy for tobacco addiction

Drug therapy is recommended for dependent smokers and when withdrawal symptoms occur to prevent relapse during the first, usually 8-12, weeks of smoking cessation and to enable the behavior change needed for long-term success in the first place [10,11]. Drug therapy doubles to triples (OR 1.82 to 2.88) the chance of quitting smoking compared with no drug therapy [15]. Three drug (groups) are approved for this purpose in Europe (exception for Switzerland: Cytisine has not been approved in Switzerland) and are also recommended in corresponding national and international guidelines [11,16,17]:

- Nicotine replacement products (patches, lozenges, chewing gum, oral spray, inhalers)

- Partial nicotinic receptor agonists (varenicline, cytisine).

- Antidepressant (bupropion)

The respective technical information [18,19] of the individual drugs must be observed before use and prescription. The most important data on the individual preparations are presented below.

Nicotine replacement therapy ( NRT).

The rationale behind this form of drug therapy is to deliver pharmacologic nicotine through the skin (patches) or oral mucosa (lozenges, gum, oral spray, inhalers) during smoking cessation, thereby avoiding or significantly reducing withdrawal symptoms. Transdermal patches deliver nicotine continuously over 16 or 24 hours, providing a baseline supply of nicotine. NRT products are available in pharmacies as over-the-counter (OTC) products.

Transdermal patch (TDM)

TDM are offered in three potencies, depending on the number of cigarettes smoked to date, and are gradually reduced over time. A daily change of the patch is required, a change of the skin site is recommended. Main side effects of patches are skin irritation and pruritus as well as headache and dizziness. Smoking must be discontinued when using TDM to avoid overdoses. TDM can also be combined with oral forms of nicotine for more severe tobacco dependence (see later in the text) to coupon acute craving attacks.

Oral forms of nicotine

Oral application of nicotine includes gum, lozenges, inhalers, and oral spray and can be used as monotherapy with a fixed application interval or only as needed or as combination therapy with TDM. Oral nicotine products are also suitable for quit attempts using the reduction method. Oral nicotine is particularly useful for craving attacks. Special features during application must be observed for the individual products (Tab. 2) . The main side effects of oral nicotine products are irritation of the oral and pharyngeal mucosa, hiccups, irritation of the esophagus and stomach, in some cases nausea and coughing. For oral spray, headache is also listed as a very common side effect (>1/10).

NRT products should be used in smokers with unstable angina, recent myocardial infarction, severe arrhythmias, recent stroke, or uncontrolled hypertension only after very careful risk-benefit consideration. The same applies to patients with pheochromocytoma and manifest hyperthyroidism. Pregnant women and nursing mothers should also be advised to stop smoking without drug support. Only after careful risk-benefit assessment can oral NRT be used in pregnant and lactating women. Diabetes patients should be advised to monitor BG levels more closely, as reduced nicotine release may affect carbohydrate metabolism. In the presence of hepatic and renal dysfunction, the dosage of NRT may need to be adjusted.

Smoking cessation may slow drug metabolism by CYP 1A2. Dose reduction may be required here, especially for drugs with a narrow therapeutic range (e.g., theophylline, tacrine, clozapine, ropinirole). Rarely, transfer of tobacco or cigarette dependence to an NRT product occurs (especially with the oral forms of administration) with the need for therapeutic intervention to slowly gradually reduce NRT dosage over weeks or months.

Partial nicotinic receptor agonists (varenicline, cytisine).

Varenicline and cytisine are included in this group. The pharmaceuticals exert a nicotinic (agonistic) effect at the receptor. At the same time, they block the receptor for a longer period of time (antagonistic effect) and make it unavailable for nicotine from tobacco cigarettes.

Varenicline was withdrawn from the market beginning in 07/21 due to elevated N-nitroso varenicline and is not yet available again. Cytisine has not been approved by the drug authorities in Switzerland and, according to current research, is not available in pharmacies in Germany either, or only to a very limited extent. Both preparations are available only on prescription in Germany.

Varenicline showed the highest long-term cessation rates in trials compared to the other drug therapies. It is given cautiously during the first week when continued inhaled smoking is still possible; the recommended maintenance dose is 2× 1 mg/d. Smoking cessation should occur during the second week of treatment. Dose adjustment is required only in severe renal insufficiency (Crea clearance <30 ml/min). Previous reports of increased neuropsychiatric or cardiovascular events have been refuted by large studies. Main side effects of varenicline are headache, nausea, gastrointestinal discomfort, and abnormal dreams. If side effects occur, the dose can be reduced to 1× 1 mg/day with still good effect in terms of smoking cessation. Cessation of therapy is not required, but is practiced by many smokers.

Cytisine is an extract of goldenseal (Laburnum) and is administered in descending doses (starting with 6× 1.5 mg/d) for 25 days. Both the mode of action and the side effect spectrum are similar to varenicline. With cytisine, tachycardia and hypertension, rash, and myalgias are still listed as very common (>1/10). Varenciline should not be used during pregnancy and lactation; for cytisine, a contraindication during pregnancy and lactation is listed in the SmPC.

Antidepressant (bupropion)

Bupropion is a non-tricyclic antidepressant and is classified as a selective reuptake inhibitor of dopamine and norepinephrine. It was approved for tobacco cessation in Germany and Switzerland in 2000. When using bupropion, a number of contraindications, interactions and side effects must be taken into account (Tab. 3) , which is why the prescription should be reserved for practitioners who have appropriate experience with the drug.

Take-Home Messages

- Every physician should advise smokers to quit and offer evidence-based support.

- Due to an existing tobacco dependence and/or the occurrence of withdrawal symptoms, many smokers require drug support in order to be able to manage the start of smoking cessation in the first place.

- There are several approved drugs/groups of drugs that can be used, taking into account the patient’s own experience and preference, and

should. - The use of medication increases the long-term chances of success by a factor of approximately 2 to 3.

Literature:

- Europäische Kommission – EU: Public Health, Tobacco Overview; https://health.ec.europa.eu/tobacco/overview_en (letzter Zugriff: 18.04.2023).

- Bundesamt für Statistik (CH): www.bfs.admin.ch/bfs/de/home/statistiken/gesundheit/determinanten/tabak.assetdetail.6466013.html (letzter Zugriff: 18.04.2023).

- Europäische Kommission: Special Eurobarometer 506: Attitudes of Europeans towards tobacco and electronic cigarettes 2021;

https://europa.eu/eurobarometer/surveys/detail/2240 (last accessed 04/18/2023). - DEBRA study: http: //debra-study.info,(last accessed 04/18/2023).

- Federal Office of Public Health (CH): www.bag.admin.ch/bag/de/home/zahlen-und-statistiken/zahlen-fakten-zu-sucht/zahlen-fakten-zu-tabak.html (last accessed: 18.04.2023).

- Effertz T: Die Kosten des Rauchens in Deutschland im Jahr 2018. Atemwegs- und Lungenkrankheiten 2019; 307–314.

- Drogenbeauftragte der Bundesregierung beim Bundesministerium für Gesundheit: Drogen- und Suchtbericht 2021.

www.drogenbeauftragte.de/service/publikationen. - Jha P, Ranasundarahettige C, Landsman V, et al.: 21st-century hazards of smoking and benefits of cessation in the United States. N Engl J Med 2013; 0364(4): 341-350.

- Kotz D, Batra A, Kastaun S: Smoking cessation attempts and common strategies employed. A Germany-wide representative survey conducted in 19 waves from 2016 to 2019 (The DEBRA Study) and analyzed by socioeconomic status. Dtsch Arztebl Int 2020; 117: 7–13; doi: 10.3238/arztebl.2020.0007.

- Fiore MC, Jaén CR, Baker TB, et al.: Treating tobacco use and dependance: 2008 update. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services 2008.

- Batra A, Petersen KU: S3-Leitlinie Rauchen und Tabakabhängigkeit: Screening, Diagnostik und Behandlung 2021; AWMF-Register Nr. 076-006.

- Mühlig S: Persönliche Korrespondenz zur ATEMM-Studie in Sachsen (no date).

- Mediverbund: Facharztvertrag Pneumologie; www.medi-verbund.de/facharztvertraege/aok-bw-bosch-bkk-pneumologie (last accessed 18.04.2023).

- Batra A, Lindinger P: Tabakabhängigkeit – Suchtmedizinische Reihe, Band 2. Hamm 2013.

- Cahill K, Stevens S, Perera R, Lancaster T: Pharmacological interventions for smoking cessation: an overview and network meta-analysis. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews(5) 2013; doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD009329.pub2.

- NICE – National Institute for Health and Care Excellence: Behaviour change: digital and mobile health interventions – NICE guideline ng183 2020; www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng183 (last accessed 18.04.2023).

- USPSTF – US Preventive Service Task Force: Interventions for Tobacco Smoking Cessation in Adults, Including Pregnant Persons – US Preventive Services Task Force Reccommendation Statement. JAMA 2021; 265–279; doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.25019.

- DIMDI: Fachinformationen Nikotinersatzprodukte;

https://portal.dimdi.de/amguifree/am/search.xhtml

(last access: 18.04.2023). - Fachinfo.de: Specialist information varenicline, cytisine, bupropion;

www.fachinfo.de (last accessed 04/18/2023).

HAUSARZT PRAXIS 2023; 18(5): 10–14