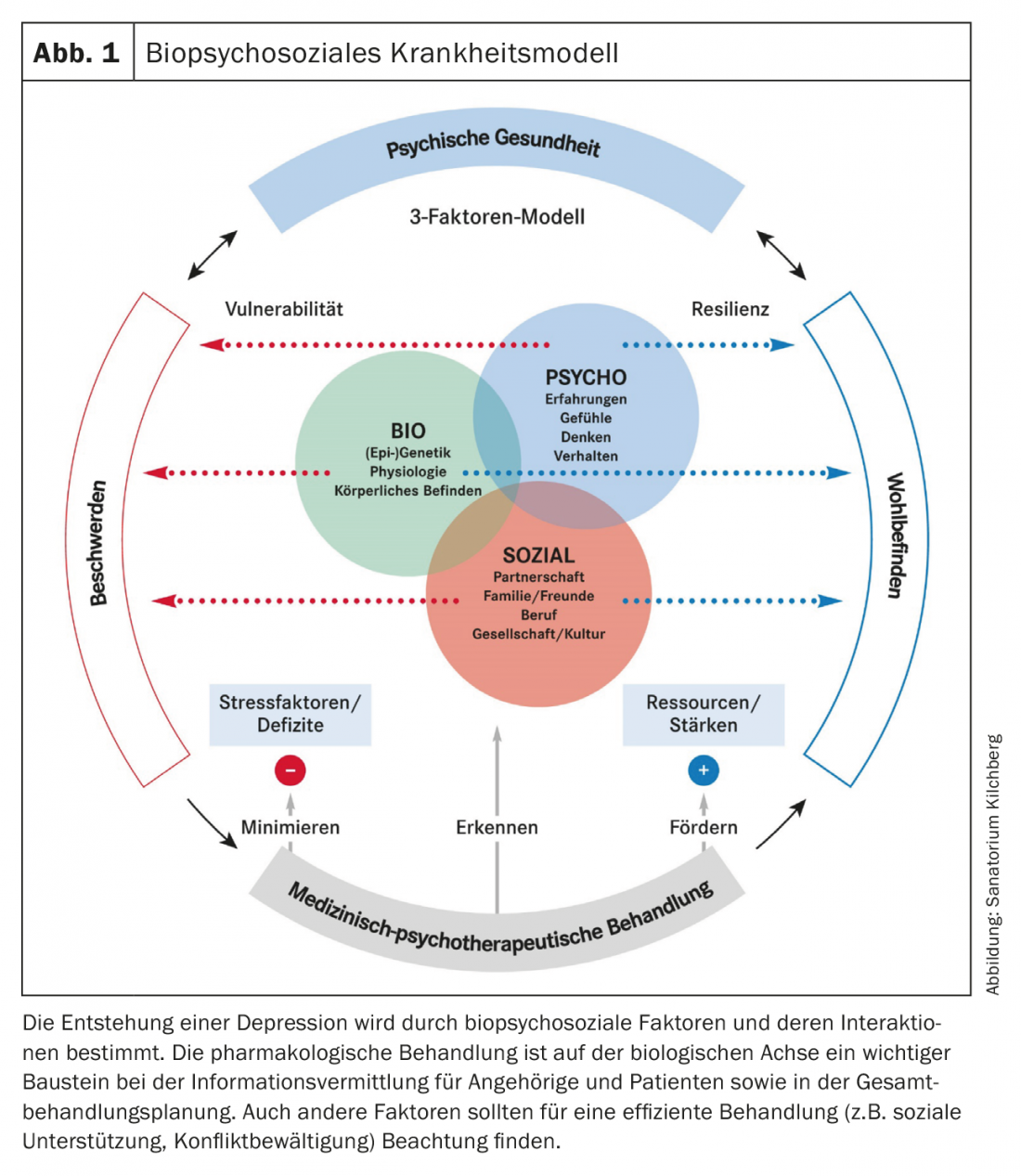

Pharmacotherapy for depression is part of an overall treatment process based on a biopsychosocial model. In general, the more severe the depression, the higher the evidence for antidepressant treatment.

Pharmacotherapy is an important pillar in depression treatment. Successful treatment of a person suffering from depression always requires a biopsychosocial perspective (Fig. 1). Many patients do not respond to initial therapy. An attitude of the physician characterized by hope and resource orientation as well as experience with different therapy strategies are essential factors in the sufficient treatment of depression.

Indication for drug treatment

The S3 guideline recommends “active-waiting support” for two weeks for mild depressive episodes “when it can be assumed that the symptoms will resolve even without active treatment.” Immediate therapy is recommended for moderate and severe episodes. While either pharmacotherapy or psychotherapy is recommended for mild and moderate episodes, the combination of both measures is the means of choice for major depression.

Overall, the evidence for pharmacological treatment of mild depressive episodes is significantly lower than for moderate and severe depression and, according to the guideline, is also recommended only at the explicit request of the patient. Pharmacological treatment is absolutely indicated for severe depression. Pharmacological treatment of severe and especially delusional depression is often also the basis for effective psychotherapeutic treatment to become possible at all.

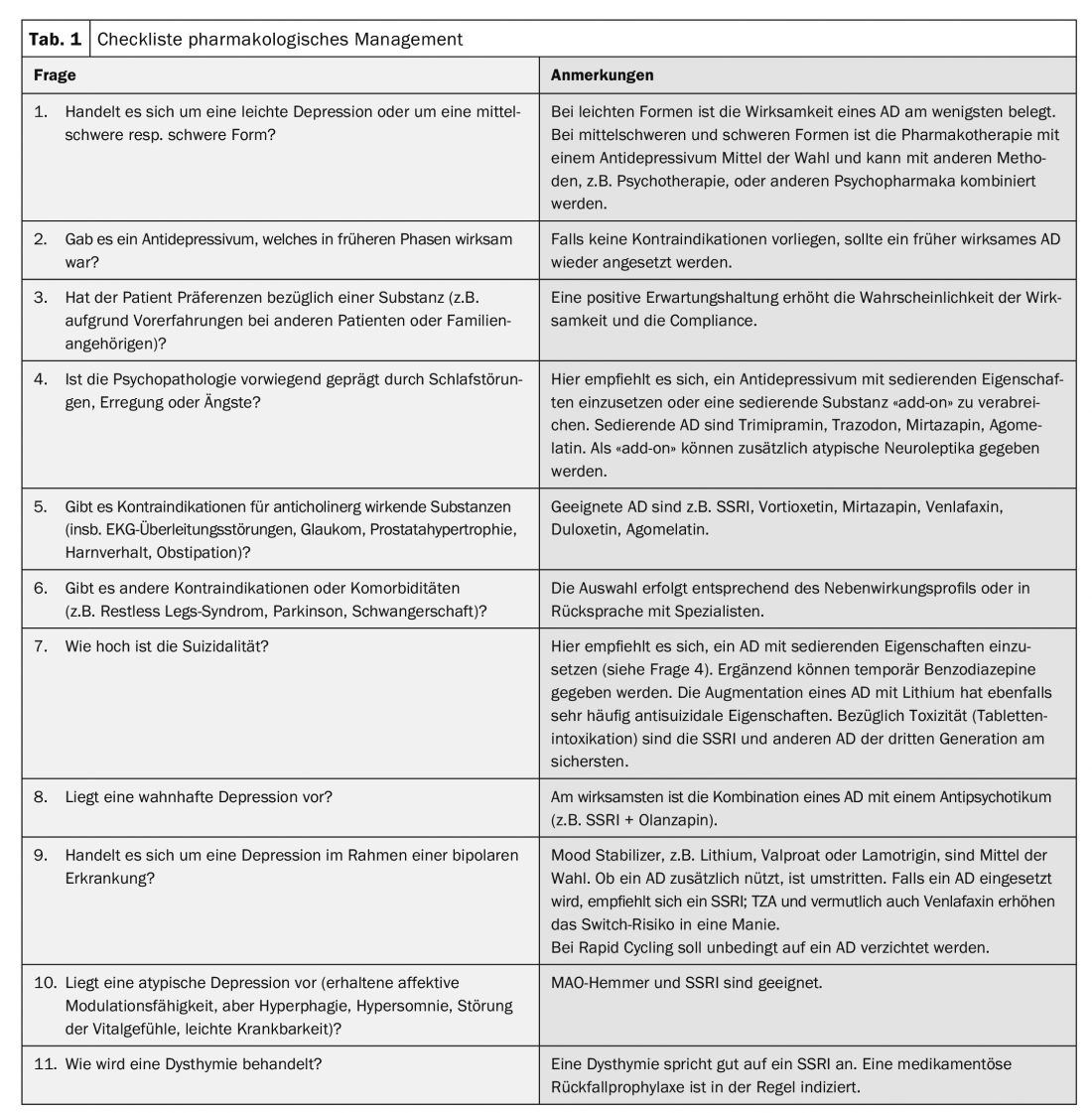

The treatment of unipolar depression differs substantially from that of bipolar depression. The article focuses on unipolar depression. Some specifics of the treatment of bipolar depression are highlighted in Table 1.

Selection of antidepressants

Efficacy comparisons and meta-analyses showed superiority of antidepressants over placebo, but no very clear differences between the different agents. This is mainly due to the often not very informative study designs or too small samples as well as the heterogeneity of the disease.

When selecting a substance, factors such as previous efficacy, comorbidities, psychopathological characteristics (especially sleep disorders, agitation, suicidality, delusions, drive disorder, anxiety), and bipolarity should be considered in addition to the physician’s experience with the substance. See Table 1 for a decision support checklist.

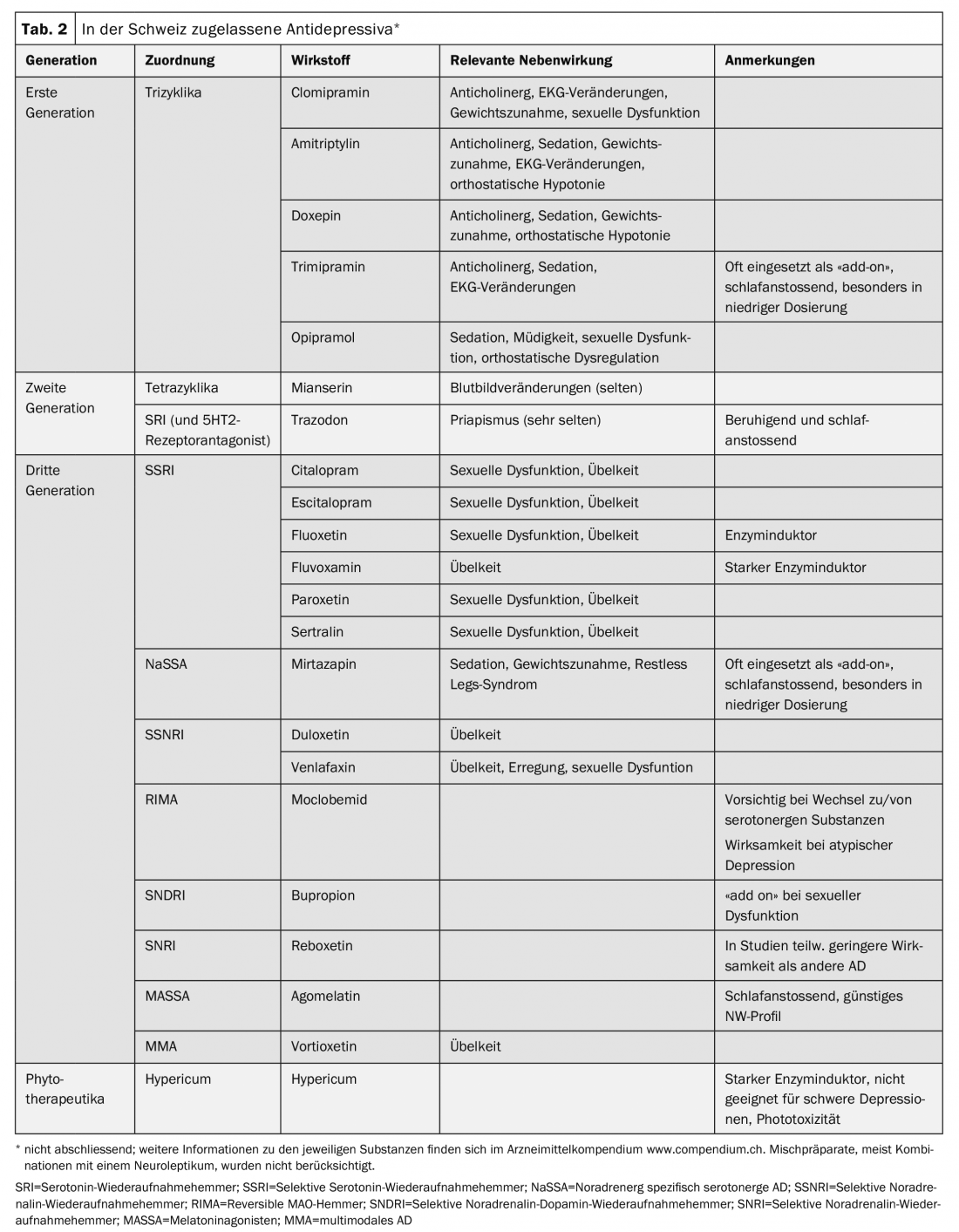

The oldest antidepressants (first generation) are the tricyclics (TCAs). Because of their side effects (e.g., anticholinergic effects, cardiotoxicity, weight gain), they are now used much less frequently than the later-developed second- and third-generation antidepressants. However, they remain an option, especially in patients with major depression who respond inadequately to other antidepressants. The antidepressants approved in Switzerland, their assignment to the mechanisms of action, and some characteristics of the substances can be found in table 2.

Motivate the patient

Since depression is often accompanied by hopelessness, anxiety, and the inability to make decisions, the physician should take plenty of time to provide individualized education and motivation for recommended treatment based on the distressing symptoms. Experience from medication history should be validated and incorporated into the participatory decision-making process for individualized treatment recommendation. Especially at the beginning of pharmacotherapy, frequent consultations (at least once a week) or telephone appointments should be scheduled to support the patient in his or her therapy. Information material, the inclusion of relatives or affected persons (“peer-to-peer”) can support this. Illness-related high ambivalence or delusional components, which may be present in major depression, may complicate readiness for adequate antidepressant therapy.

Dosing and routine controls

Antidepressants are dosed gradually. According to guidelines, the average daily dosage should be reached within the first week. Within the first three weeks, there should be an improvement in symptoms. The latency of action in older patients is often longer (about six weeks). In addition, therapy should be started with lower doses in the elderly.

Since some antidepressants have side effects, especially at the beginning, which often decrease or disappear in the course of treatment (e.g., nausea or increased anxiety with SSRIs), it is necessary to inform patients in advance about the time course in order to support them in not discontinuing the medication too early. In particular, patients with a history of drug therapy discontinuations due to side effects benefit from a longer up-dosing period. The administration of antidepressants in drop form (escitalopram, paroxetine, sertraline, vortioxetine) is suitable for this purpose.

As a rule, one starts with monotherapy. In the case of a high burden of sleep disturbances, circling thoughts, fears and suicidal thoughts, a combination therapy may also be useful (activating AD + sedating AD or atypical neuroleptic; temporary, i.e. lasting max. 3-4 weeks, addition of benzodiazepines). In delusional depression, combination therapy of an antidepressant and an atypical neuroleptic is indicated from the onset.

Prior to initiation of antidepressant therapy, a blood draw (blood count, creatinine, liver enzymes, electrolytes, TSH, blood glucose, HbA1c), measurement of vital signs and body weight, and an ECG are performed for routine monitoring, education about side effects including potential increase in suicidal ideation, and information about driving ability.

Depending on the substance, comorbidity, age, complaints and side effect profile, control examinations (usually ECG, blood count, liver and kidney values) are recommended initially at one-month intervals (for further information on the respective substance, see www.compendium.ch).

What to do in case of insufficient response?

People often wait too long to change their treatment strategy. However, in case of non-response, a change in the therapeutic strategy should be made after the fourth week of treatment with a standard dose. At least fifty percent improvement is defined as a relevant response. Screening instruments (“Montgomery and Asberg Depression Rating Scale,” MADRS; “Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression,” HAMD) that record symptom development are useful as tools for this decision-making process.

In case of non-response (non-response: <25% improvement) or insufficient improvement (partial response: 25-49% improvement), there are several pharmacological options:

- The antidepressant is dosed up. Therapeutic drug monitoring can assist in decision-making regarding further action by providing evidence of missing or irregular intake of the substance and of decreased or increased plasma levels due to metabolic variants (including altered metabolism due to co-medication). Evidence exists primarily on TZA and venlafaxine. In case of repeated non-response and severe side effects, CYP genotyping (not a basic insurance benefit) may be considered.

- The antidepressant substance is changed. A switch to a substance with a different mechanism of action is recommended.

- A combination therapy of two antidepressants is installed (“add on”, especially SSRI + mianserin or mirtazapine).

- Augmentation therapy is performed, meaning the antidepressant is supplemented with another substance. Lithium (high evidence, especially in suicidality) or an atypical neuroleptic (e.g., quetiapine, olanzapine, risperidone, aripiprazole, amisulpride) is suitable for this purpose. Augmentation strategies (with lower evidence) also include thyroid hormones, lamotrigine (esp. bipolar depression), pramipexole, methylphenidate, and buprenorphine. Most of the substances used for augmentation are off-label, which entails an especially careful duty to inform the patient.

For all changes, regular monitoring of the effect and side effects (at least once a week) is indicated. In principle, an antidepressant should not be discontinued abruptly, but rather phased out. With abrupt discontinuation, discontinuation phenomena are described in some patients (such as with venlafaxine and paroxetine).

Guidance for antidepressant selection and dose adjustment is provided by genotyping of ABCB1 variants, which influence the pharmacokinetics of many antidepressants. The ABCB1 test is not a mandatory health insurance benefit.

TCAs as infusion therapy were a relevant option for the treatment of treatment-resistant major depression until a few years ago, especially in the inpatient setting. Unfortunately, the ampoules for infusion therapies (clomipramine, maprotiline) are no longer commercially available; maprotiline is also no longer available for oral administration.

The therapeutic goal is remission whenever possible (MADRS ≤10; HAMD ≤7).

Recommendations for the duration of intake

A common patient request is to discontinue antidepressants after acute therapy, when depressive symptoms have disappeared or improved significantly. Since the risk of relapse after an acute episode is high, maintenance therapy of six to nine months (due to the positive effects in terms of neuroplasticity) at the same dosage is recommended. The risk of relapse is particularly high in severe and psychotic depression. If the patient and physician decide to reduce or completely discontinue drug treatment, this should be done gradually and with regular monitoring.

If patients have recurrent depressive episodes, further antidepressant treatment is useful as relapse prophylaxis after maintenance therapy; duration and dose depend on the frequency and severity of depressive episodes.

Alternative or complementary antidepressant therapy options.

In addition to pharmacologic therapy, other biologic and psychotherapeutic therapies, as well as mindfulness-based practices, are available that can be used as monotherapy or to complement pharmacotherapy with the goal of achieving remission or at least the best possible response of depressive symptomatology. Support in the social sphere, e.g. for financial and professional problems, single-parent families or situations of exclusion, also have positive effects.

Electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) has been described as the treatment of choice for severe depression that responds inadequately to other therapeutic modalities. Other established biologic procedures include light therapy (first-line agent for seasonal-dependent depression) and awake therapy.

There is also evidence of efficacy for repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation, vagus nerve stimulation, transcranial direct current stimulation, deep brain stimulation, ketamine treatment, and Botox therapy. Sex hormones, omega-3 fatty acids and vitamin substitutions (folic acid, vit. B12, vit. B6, vit. D) are also discussed in the scientific literature. They are not yet considered a basic insurance benefit in depression treatment, and light therapy also usually requires an application for coverage. The activating and mood-stabilizing effect of regular exercise can be additionally mentioned as a biological therapy method.

There is good evidence for psychotherapeutic therapies (esp. cognitive behavioral therapy, interpersonal therapy, schema therapy, Cognitive Behavioral Analysis System of Psychotherapy [CBASP]), both alone and in combination. The combination of pharmacotherapy with psychotherapeutic treatment seems particularly suitable in terms of efficiency and sustained effectiveness. The more severe the depression, the more pharmacological therapy is indicated.

Take-Home Messages

- Pharmacotherapy for depression is part of an overall treatment process based on a biopsychosocial model.

- First-choice drugs are usually the third-generation substances.

- The selection of the substance is based on the patient’s previous experience, severity and psychopathological abnormalities, comorbid conditions, and the side effect profile of the antidepressant.

- If there is no response to an antidepressant after three to four weeks, a change in treatment strategy should be sought.

- The more severe the depression, the higher the evidence for antidepressant treatment.

- In delusional depression, combination with an atypical antipsychotic is indicated.

Further reading:

- American Psychiatric Association (APA): Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with major depressive disorder. 3rd edition, 2010. https://psychiatryonline.org/pb/assets/raw/sitewide/practice_guidelines/guidelines/mdd.pdf, last accessed 02/28/19.

- Benkert O, Hippius H, eds: Compendium of Psychiatric Pharmacotherapy, 12th edition. Berlin: Springer, 2019.

- Cipriani MD, et al: Comparative efficacy and acceptability of 21 antidepressant drugs for the acute treatment of adults with major depressive disorder: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. Lancet 2018; 391(10128): 1357-1366.

- Daly EJ, et al: JAMA Psychiatry 2018; 75(2): 139-148.

- DGPPN: Unipolar depression. S3 Guideline and National Health Care Guideline (NVL), 2nd edition, 2015. www.dgppn.de/_Resources/Persistent/d689bf8322a5bf507bcc546eb9d61ca566527f2f/S3-NVL_depression-2aufl-vers5-lang.pdf, letzter Abruf 28.02.19.

- Liu B, et al: Front Cell Neurosci 2017; 11: 305.

- NICE Guidance: Depression in adults: recognition and management. October 2009 (update April 2018). www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg90, last accessed 02/28/19.

- Schuch FB, et al: Am J Psychiatry 2018; 175(7): 631-648.

- SGAD, SGPP: Treatment recommendations: The Somatic Treatment of Unipolar Depressive Disorders, Parts 1 and 2, 2016. www.psychiatrie.ch/sgpp/fachleute-und-kommissionen/behandlungsempfehlungen, last accessed 02/28/19.

- Tondo L, Baldessarini RJ: Pharmocopsychiatry 2018; 51(5): 177-188.

- Voderholzer U, Hohagen F, eds: Therapie psychischer Erkrankungen. State of the art, 14th edition. Munich: Elsevier, 2018.

InFo NEUROLOGY & PSYCHIATRY 2019; 17(2): 20-25.