Diarrhea is defined as three or more unformed bowel movements within 24 hours. If the symptoms resolve within 14 days, the condition is referred to as “acute” diarrhea [1]. The etiology of diarrhea is diverse and includes infections as well as numerous noninfectious causes. Indications of an infectious event may include acute onset, fever, and temporally clustered occurrence [1]. Community-acquired acute infectious diarrhea is common, usually self-limiting, and therefore leads to consultation only exceptionally and in more severe cases. This article discusses the microbiological workup of symptomatic patients with acute diarrhea and suspected infectious etiology. Persistent (>14 days) or chronic (>four weeks) diarrhea is not a focus.

Regardless of the mechanism, most bacterial gastroenteritis is self-limiting and, with few exceptions, does not require empiric antibiotic therapy or the ordering of stool cultures: by the time their results arrive, most patients’ symptoms have disappeared, i.e., stool cultures do not usually contribute to patient care [2]. According to the guidelines of the American Society of Gastroenterology, this excludes clinically severe cases with severe, persistent diarrhea and dehydration, fever above 38.5°C, and blood in the stool [3]. Special diagnostic considerations are also indicated for travelers returning to the country, immunocompromised patients, and hospital-associated diarrhea and temporally clustered cases of illness.

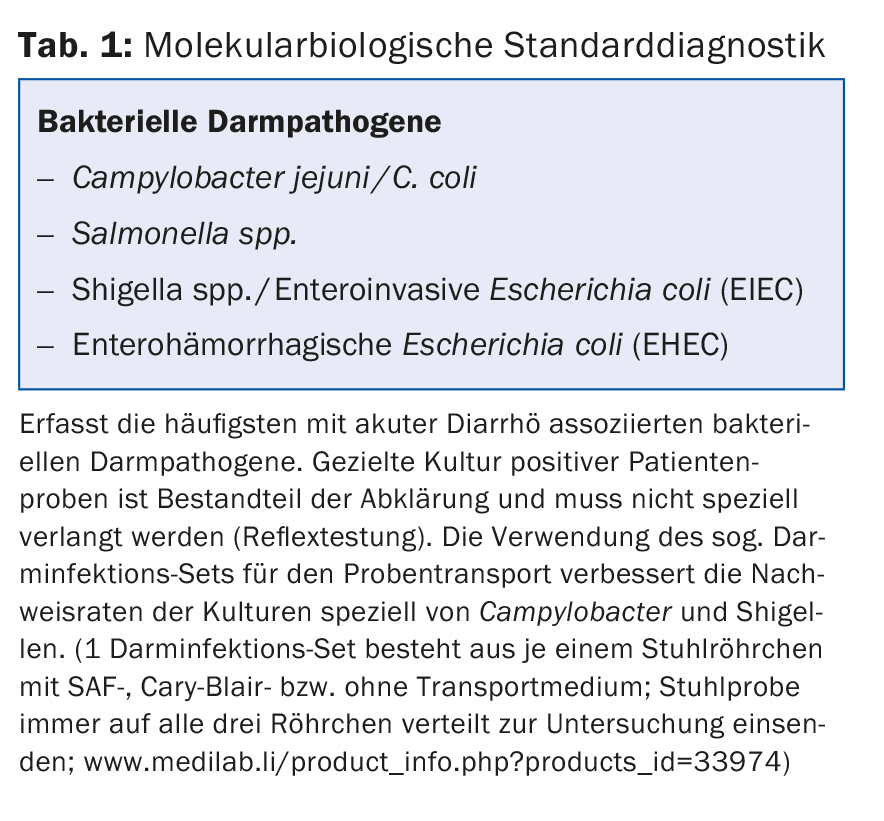

Standard molecular diagnostics – General stool bacteriology

In the microbiological clarification of acute, community-acquired bacterial diarrhea, molecular biological methods for the detection of the most common bacterial intestinal pathogens (Tab. 1) are much more sensitive compared to culture and are hardly influenced by improper preanalytics or by antibiotic administration. Concerns that molecular biological methods detect pathogen-specific but biologically inactive nucleic acids are unfounded, at least for Campylobacter infections, as we have recently shown: Intestinal inflammatory response and pathogen load are directly correlated in Campylobacter infections[4]. Experience to date has shown that the prompt availability of test results is of particular importance for initial patient care. Cultures are only established secondarily when there is positive molecular biological evidence of the pathogen (“reflex testing”) in order to have the patient isolate available for resistance testing and epidemiologically significant additional investigations (e.g. serotyping).

The zoonotic pathogens Campylobacter, non-typhoidal Salmonella, and EHEC, along with Shigella, are among the four most commonly reported bacterial enteric pathogens in the United States [5]. Accordingly, the most common bacterial intestinal pathogens are detected with standard molecular biological diagnostics (Tab. 1) . For example, Switzerland records over 7000 laboratory-confirmed Campylobacter infectionsannually, with clusters in summer during the barbecue season and over the festive season at the end of the year [6]. Therefore, in a given clinical-epidemiological context – for example, in the case of clinical suspicion of Campylobacter infection during the Christmas holidays – the initiation of standard diagnostics to clarify acute diarrhea may be sufficient and appropriate. Due to the use of culture-independent methods, the test result is usually available on the same day. There is no need to send several patient samples per episode, which is due on the one hand to the prompt availability of the test results and on the other hand to the high sensitivity of molecular biological methods. In our experience, the treating physicians still do not take this circumstance sufficiently into account; in our view, not sending more than one sample per patient and episode has some potential for savings.

All stool samples that test positive are specifically cultured in order to have the respective patient isolate available for resistance testing and other epidemiologically significant additional investigations, such as serotyping of Salmonella (reflex testing). These results are usually available days later because culture-based methods are time-consuming. It is also not uncommon for patient isolates to be referred to the National Center for Enteropathogenic Bacteria and Listeria (NENT) for further characterization or confirmation [7].

In the course of cultural processing of stool samples positive for molecular biology, we observe from time to time that the culture media applied remain negative and the indicated pathogen cannot be cultured. This phenomenon occurs particularly often in the cultivation of Campylobacter and Shigella. In this context, there is an opportunity to point out the importance of preanalytics and sample transport for cultural pathogen detection. Fresh stool specimens should be processed in the laboratory within two hours of collection; this is especially critical for Campylobacter and Shigella survival. If a fresh stool specimen cannot be processed in the laboratory within two hours of collection, it should be placed in a tube containing Cary-Blair transport medium and sent to the laboratory [2].

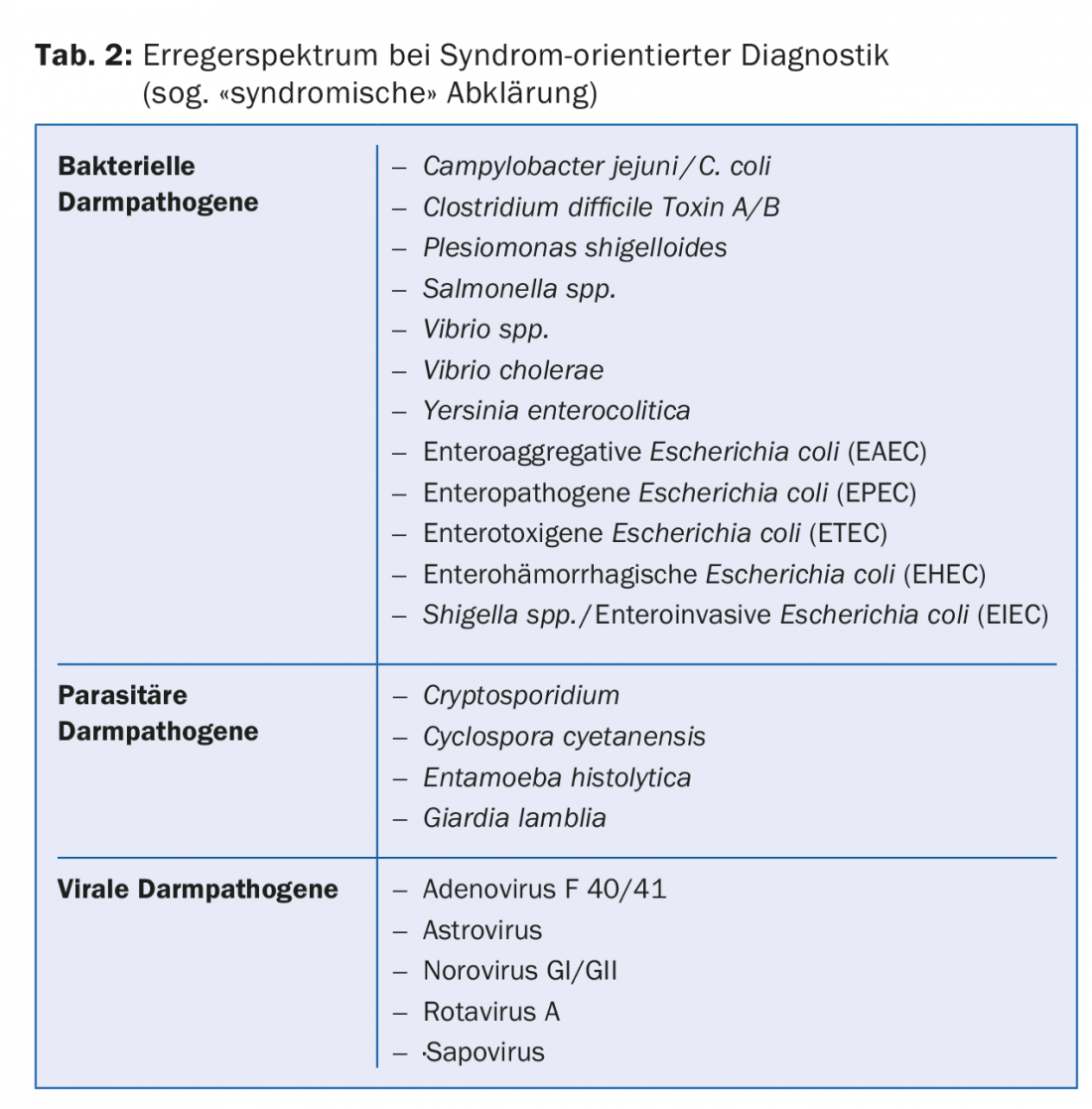

Syndrome-oriented diagnostics

Syndrome-oriented diagnostics means the use of molecular biological methods with which patient samples can be simultaneously tested for the presence of more than 20 bacterial, parasitic and viral pathogens, depending on the clinical presentation or the syndrome present. The composition of the pathogen batteries is based on global data on the epidemiology of each pathogen (Table 2).

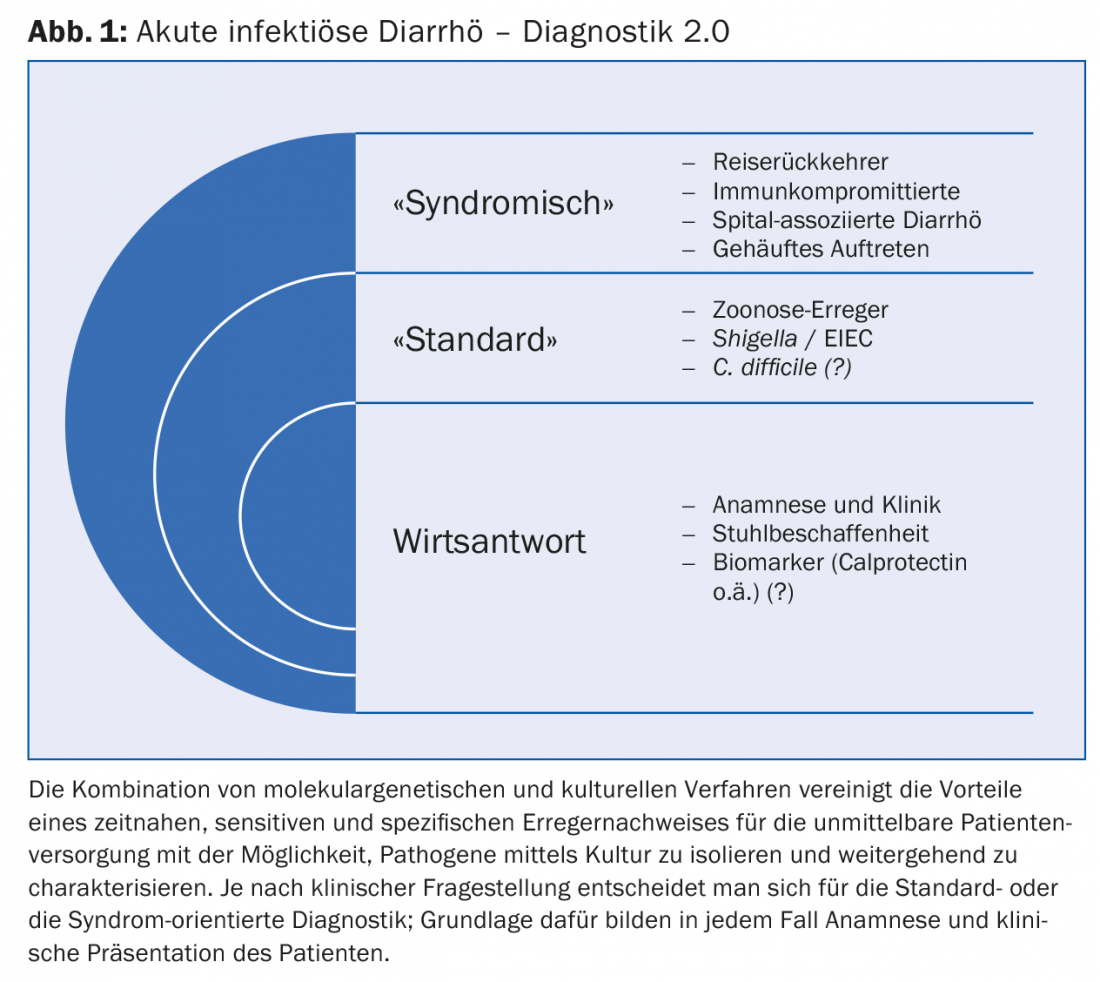

In contrast to the standard procedure, pathogens that do not correspond to the local epidemiology are also recorded. This makes the use of pathogen batteries particularly valuable in the workup of travelers and immunocompromised patients with suspected acute infectious diarrhea. A syndrome-oriented assessment can also be helpful in connection with hospital-associated cases of illness or when cases of illness of unclear etiology occur more frequently over time (Fig. 1).

Multiple infections

The use of broad pathogen batteries in the initial microbiological workup of acute diarrhea makes it increasingly evident that multiple infections are probably more common than previously thought, even in our country [8]. In our experience, multiple infections with two or more potential intestinal pathogens are found especially in travelers returning home. This is consistent with the findings of the Global Enteric Multicenter Study (GEMS), which prospectively studied over 9000 children aged up to five years with moderate to severe diarrhea in seven countries in Africa and Southeast Asia during a 36-month period [9]. In a total of 45% of these children, more than one intestinal pathogen was identified. Remarkably, even in the healthy controls, more than two potential intestinal pathogens were identified in 31% of cases.

Diagnostics 2.0

The combination of molecular genetic and cultural methods (Diagnostics 2.0) combines the advantages of prompt, sensitive and specific pathogen detection for immediate patient care with the possibility to isolate and further characterize pathogens by culture. Acute infectious gastroenteritis is common, usually self-limiting, and only exceptionally leads to consultation. In severe cases, microbiological workup may be indicated [3]. Today, thanks to technological progress, we have various diagnostic options at our disposal. Initial indications are provided by the patient’s medical history and clinical presentation (Fig. 1) . Common to all diagnostic options is the prompt availability of test results, usually on the same day if the patient sample arrives before 11 hrs.

Standard diagnostics

Standard diagnostics are sufficient to detect the bacterial intestinal pathogens most commonly associated with acute diarrhea. The specific culture of positive patient samples is part of the clarification and does not have to be specifically requested (reflex testing). The use of the so-called intestinal infection set for sample transport improves the detection rates of cultures especially of Campylobacter and Shigella. Patient isolates are available for additional testing, such as resistance testing.

Depending on the clinical context, standard diagnostics are not infrequently extended to include selective detection of noroviruses and/or toxin-producing Clostridium difficile. These two analyses also provide same-day results.

Use of broad exciter batteries

Syndrome-oriented diagnostics may be superior to standard diagnostics in selected cases. In our opinion, these include travelers and immunocompromised patients as well as selected cases of hospital-associated diarrhea and an unclear temporal clustering of cases of illness. Here too, if possible, the specific culture of positively tested patient samples is part of the clarification (reflex testing); the so-called intestinal infection kit is recommended for sample transport.

Travel Return

Enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli (ETEC) are responsible for travelers’ diarrhea in up to 50% of cases; thus, they are the most important cause of travelers’ diarrhea overall [1]. Enteroaggregative E. coli (EAEC) and enteroinvasive E. coli (EIEC) also play a significant role here and, like ETEC, are not detected by standard diagnostics. Multiple infections are relatively common.

Immunocompromised patients

Gastrointestinal complaints are relatively common in immunocompromised patients and are not infrequently chronic. In this context, differentiating acute infectious diarrhea from a transient exacerbation in the setting of the underlying condition may be difficult, especially because more rare potential intestinal pathogens may be causative in addition to common ones due to immunodeficiency. Here, syndrome-oriented diagnostics offers undoubted advantages by covering a broad spectrum of bacterial, parasitic and viral intestinal pathogens and also detects multiple infections.

Hospital-associated diarrhea

Gastrointestinal discomfort and diarrhea are relatively common in the hospital setting and may be due to disruption of intestinal flora due to antibiotic therapy. Diarrhea caused by toxin-producing Clostridium difficile, which is also increasingly being acquired in outpatients, must be distinguished from this [5]. In emergency departments, effective triage of patients with infectious diarrhea is also important from a hospital hygiene perspective: pathogens with low infectious doses, such as shigella and EHEC, but also protozoa and viruses, are particularly easily transmitted to other persons and carry the risk of hospital epidemics [5]. Prompt identification of these patients is thus in the interest of both patient and institution.

Temporal accumulation of cases of disease of unclear etiology

When there is a temporal accumulation of disease cases with an unproductive history and little characteristic clinical presentation, syndrome-oriented workup of the first cases of disease can be a simple and ultimately cost-effective way to clarify an unclear situation in a timely manner.

Conclusion

“I envisage that in the near future, conventional laboratory methods directed at isolating specific pathogens will become second-line tools to be deployed only when multiplex screening deems it necessary,” wrote Prof. Franz Allerberger of Austria’s Agency for Health and Food Safety (AGES) [10]. The advantages of molecular biological, culture-independent pathogen detection lie primarily in the prompt availability of the test results and the relative insensitivity to interferences during sample collection and transport. Possible disadvantages are that only known pathogens can be searched for and detected; emerging pathogens or variants of known pathogens may remain undetected, although they are clinically relevant. The combination with cultural detection methods combines the advantages of prompt, sensitive and specific pathogen detection for immediate patient care with the possibility of isolating pathogens by culture and characterizing them further.

Reprinted with kind permission of Labormedizinisches Zentrum Dr. Risch AG, 3097 Bern-Liebefeld. First published in Riport 81 (Spring 2016): www.risch.ch/de/10123/riport.html.

Literature:

- Mandell, Douglas, and Bennett’s Principles and Practice of Infectious Diseases,8th ed. 2015.

- Humphries RM, et al: Laboratory diagnosis of bacterial gastroenteritis. Clin Microbiol Rev 2015; 28: 3.

- DuPont HL: Guidelines on acute infectious diarrhea in adults. The Practice Parameters Committee of the American College of Gastroenterology. Am J Gastroenterol 1997; 92: 1962.

- Wohlwend N, et al: Evaluation of a multiplex real-time PCR assay for detecting major bacterial enteric pathogens in fecal specimens: intestinal inflammation and bacterial load are correlated in Campylobacter infections. J Clin Microbiol 2016; 54: 2262-2266.

- DuPont HL: Bacterial Diarrhea. New Engl J Med 2009; 361: 1560.

- www.blv.admin.ch/themen/04678/04711/04777/index.html?lang=de

- www.ils.uzh.ch/Diagnostik/NENT.html

- Spina A, et al: Spectrum of enteropathogens detected by the FilmArray GI Panel in a multicenter study of community-acquired gastroenteritis. Clin Microbiol Infect 2015; 21: 719.

- Kotloff KL, et al: Burden and aetiology of diarrhoeal disease in infants and young children in developing countries (the Global Enteric Multicenter Study, GEMS): a prospective, case-control study. Lancet 2013; 382: 209.

- Allerberger F: Acute diarrhea: new perspectives. Clin Microbiol Infect 2015; 21: 717.

GP PRACTICE 2016, 11(12): 40-45