The annual incidence of malignant melanoma has steadily increased over the past 40 years. While the prognosis is good in the early stages, it worsens as the tumor stage increases. Adjuvant therapy using checkpoint or BRAF/MEK inhibitors has had a lasting impact on the management of advanced cases and continues to be in flux.

The annual incidence of malignant melanoma has steadily increased over the last 40 years, varying within Europe from 3-5/100,000 in Mediterranean countries to 12-35/100,000 in Nordic countries. In this context, 80% of malignant melanomas are diagnosed at a localized stage. For early-stage melanoma, surgical resection is the standard treatment and is associated with a good long-term prognosis. Five-year overall survival (OS) is 65-100% for stage I-II disease and decreases for patients with local metastases (stage III) to 41-71% and in patients with distant metastases (stage IV) to 9-28% [1].

Classification of melanoma and molecular genetic alterations.

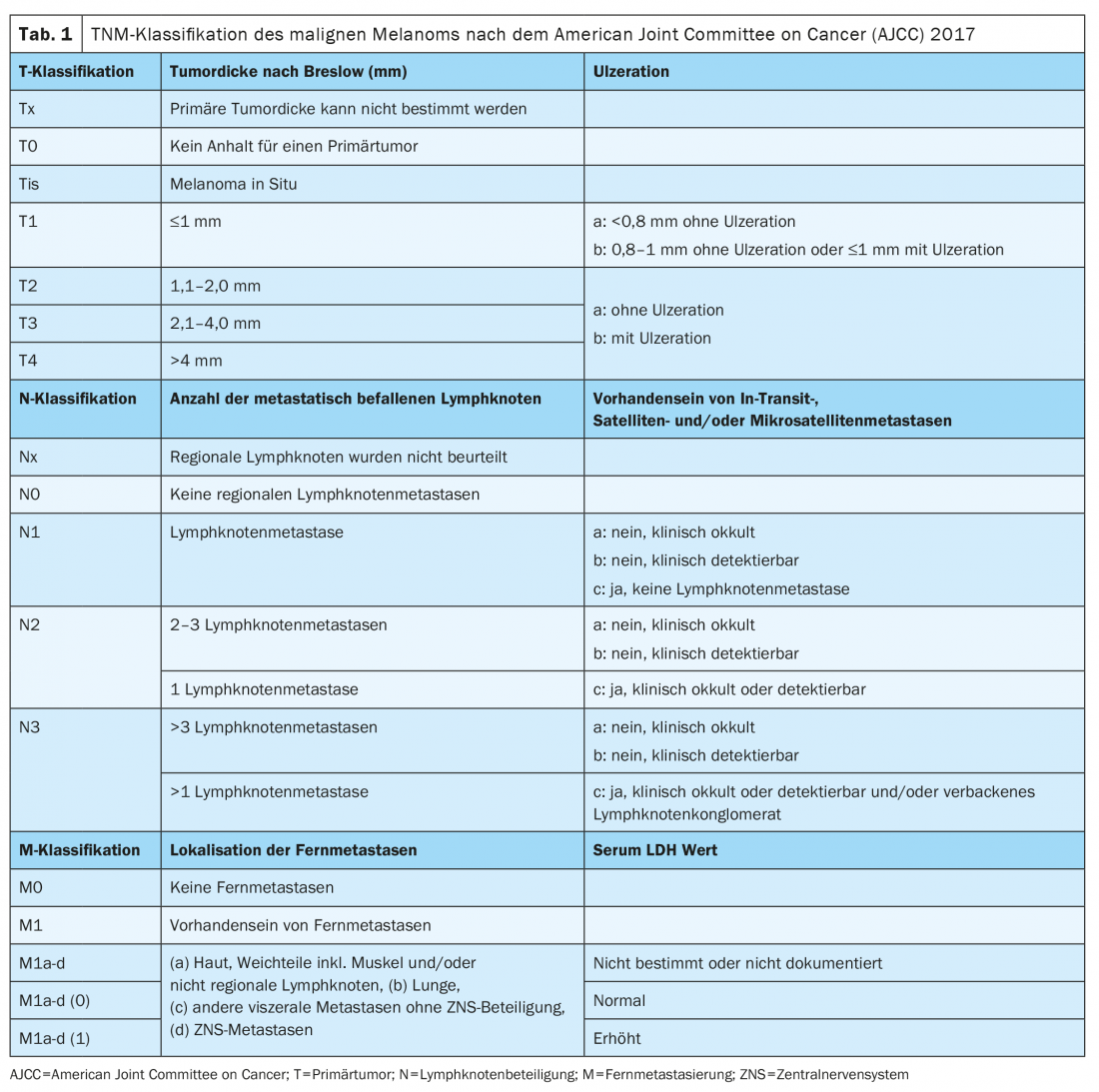

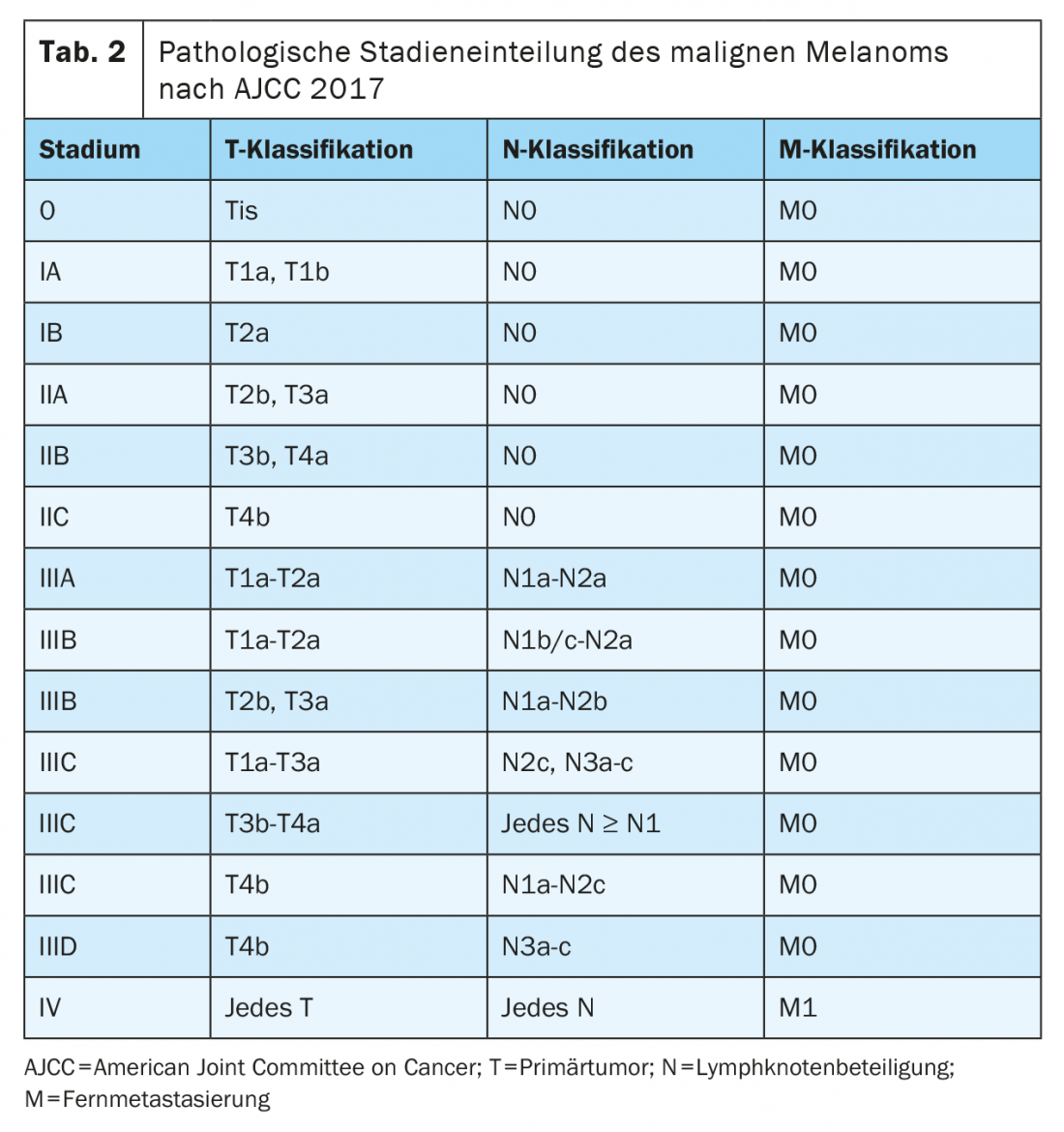

Since January 2018, the classification of melanoma has been according to the 8th edition of the AJCC staging manual (Tables 1 and 2) . The vertical tumor thickness according to Breslow is the most important prognostic factor and is taken into account when determining further treatment, including the required safety margins and the need for sentinel lymph node biopsy. The presence of ulceration is another relevant histopathological marker, which is associated with a worse prognosis and is recorded in the T stage of the TNM classification.

Molecular pathologic diagnosis using next generation sequencing (NGS) to determine BRAF status should be performed in locally advanced or metastatic stage III and IV melanoma. Immunohistochemical examination only allows detection of a V600E mutation, whereas V600K and other, atypical mutations cannot be detected. The Genomic Classification of Cutaneous Melanoma provides for division into four subtypes: BRAF mutation melanomas (50%); N-Ras, K-Ras, or H-Ras mutations (25%); NF1 mutation (15%); and triple wild-type melanomas (10%) [2].

Despite significant progress in understanding the genetic basis of melanoma, the use of genetic alterations for diagnostic, prognostic, or therapeutic purposes remains limited. BRAFV600E/K mutation status is predictive of treatment with BRAF inhibitors. Although there are currently no established targeted therapies for the other genetic alterations, these provide important information for study inclusion as well as potential future therapeutic approaches.

Surgical therapy of the primary tumor and regional lymph nodes

If malignant melanoma is clinically suspected, in toto excision should be performed. After histopathologic confirmation of a malignant melanoma, the primary treatment is local excision with an adequate safety margin, depending on the tumor thickness according to Breslow (0.5 cm for in situ melanomas, 1 cm for melanomas with a tumor thickness up to 2 mm, 2 cm from a tumor thickness of 2 mm). Adequate safety margin is associated with a reduction in local recurrence rate without improving overall survival [3]. For localizations in the facial or genital area, the recommended safety distance may be adjusted if significant morbidity must be assumed despite reconstructive surgery. It must be emphasized that safety distances should not be reduced for aesthetic reasons.

Sentinel lymph node biopsy (SLNB) is recommended in the ESMO guidelines for a pT1b (i.e., Breslow tumor thickness of >0.8 mm or <0.8 mm with ulceration) stage according to AJCC 8th edition. The prospective MSLT-I study validated the prognostic value and contribution of sentinel lymph node (SLK) to staging without demonstrating a survival benefit for this procedure [4]. Until 2017, complete lymph node dissection for positive sentinel lymph node was considered the standard treatment. In both the German DeCOG-SLT study and the international MSLT-2 study, regular sonographic follow-up of the lymphatic drainage area was compared with complete lymph node dissection (LND) for positive SLK [5,6]. Both studies found increased morbidity (lymphedema) but no significant improvement in melanoma-specific survival. Therefore, as of 2019, LND for positive sentinel lymph node is no longer recommended in ESMO guidelines [7]. However, LND is still recommended for macroscopic lymph node involvement. It should be noted that, on the one hand, both studies were conducted before the introduction of adjuvant systemic therapies and, on the other hand, lymph node dissection was performed in the study populations of each of the adjuvant therapies [8–10].

Adjuvant system therapy

After complete resection with an adequate margin of safety and tumor freedom, patients with stage IIB, IIC, III, and IV melanoma are at significant risk of recurrence. Adjuvant systemic therapy should be considered in these tumor stages to reduce the risk of local recurrence and distant metastases and improve overall survival. Immune checkpoint inhibitors and targeted therapies are currently approved in the U.S. and Europe for adjuvant treatment of completely resected melanoma in stages III and IV and reduce the risk of recurrence by approximately 50%. Indications and approvals vary by study inclusion criteria. It should be noted that the staging of these study populations was based on the AJCC 7th Edition 2009.

Adjuvant targeted therapy with BRAF and MEK inhibitors.

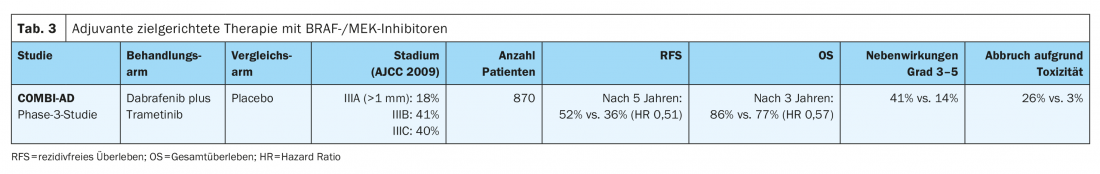

In the phase III COMBI-AD trial (Table 3) , patients with completely resected melanoma with a BRAFV600E/K mutation in stages IIIA (SLK metastasis >1 mm), IIIB, and IIIC were treated for 12 months with targeted peroral therapy with the BRAF and MEK inhibitors dabrafenib and trametinib or placebo. At a median follow-up of five years, significant improvement in recurrence-free survival (RFS) (hazard ratio HR 0.51) and also metastasis-free survival (HR 0.55) was demonstrated for this adjuvant therapy compared with placebo. The combination also improved overall survival (OS) at three years (HR 0.57). The benefit could be documented in all subgroups [8,11]. Subsequently, targeted therapy with dabrafenib and trametinib received EU-wide approval in August 2018 for the adjuvant treatment of lymphogenic metastatic malignant melanoma with BRAFV600E/K mutation.

The BRIM8 trial compared adjuvant monotherapy with the BRAF inhibitor vemurafenib to placebo in resected stage IIC-III melanoma. The primary endpoint of prolonging disease-free survival was not met in the study, making monotherapy with a BRAF inhibitor in the adjuvant setting not a therapeutic option.

Adjuvant immunotherapy

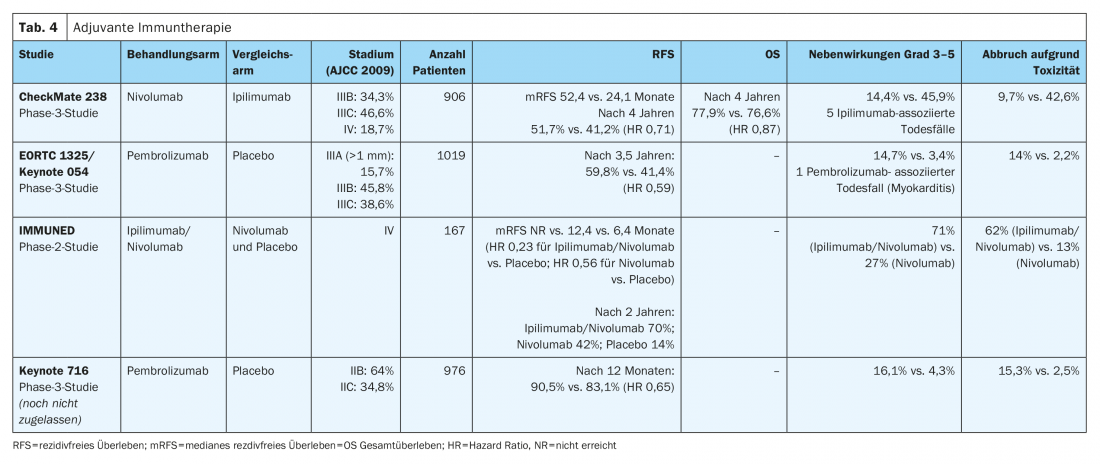

In the CheckMate-238 study (Table 4) . adjuvant intravenous therapy with the anti-PD-1 monoclonal antibody nivolumab (3 mg/kg) showed a significant improvement in recurrence-free survival (HR 0.71) and metastasis-free survival (HR 0.79) at four years for completely resected stage IIIB/C and IV melanomas compared with the high-dose anti-CTLA4 antibody ipilimumab (10 mg/kg). Overall survival at four years was comparable in the two treatment arms (HR 0.87). In addition, significantly fewer serious adverse events (grades 3-5) with consecutive treatment discontinuation occurred with nivolumab compared with high-dose ipilimumab (9.7% vs. 42.6%). Late toxicities outcomes were similar in the two treatment arms (1% vs. 2%) [10,12]. Nivolumab was approved EU-wide in 2018 for adjuvant therapy of malignant melanoma in stages III and IV after complete metastasectomy.

The efficacy of the anti-PD-1 antibody pembrolizumab was evaluated in the phase III EORTC1325/Keynote-54 trial in patients with completely resected stage IIIA melanoma (sentinel lymph node metastasis >1 mm), IIIB or IIIC (without in-transit metastases) was demonstrated (Table 4). At a median follow-up of three years, pembrolizumab was associated with significantly longer recurrence-free survival compared with placebo in the overall population (HR 0.56). Serious adverse events (grades 3-5) were observed more frequently with pembrolizumab than with placebo (14% vs. 3%) [9]. Pembrolizumab received EU-wide approval for this indication in January 2019.

The positive effect in terms of improvement in relapse-free survival was observed in all predefined subgroups in both the EORTC1325/Keynote-054 trial and the CheckMate-238 trial. In both studies, the immune checkpoint inhibitor was administered for a total therapy duration of one year in each case.

The preliminary results of the randomized phase III CheckMate 915 trial (Table 4). show no improvement in recurrence-free survival of patients with advanced, resected stage IIIB-D or IV melanoma receiving adjuvant therapy with nivolumab (240 mg every 2 weeks) in combination with ipilimumab (1 mg/kg every 6 weeks) for a total treatment duration of 12 months compared with nivolumab monotherapy (480 mg every 4 weeks). These results differ significantly from the results of the adjuvant phase II IMMUNED trial (Table 4). This study demonstrated clear superiority of adjuvant combination therapy with nivolumab (1 mg/kg) and ipilumumab (3 mg/kg) for 4 cycles every 3 weeks over monotherapy with nivolumab (3 mg/kg) every 2 weeks or placebo in patients with stage IV malignant melanoma without evidence of disease after surgery. The hazard ratio for recurrence was 0.23 in the nivolumab/ipilimumab group compared with the placebo group and 0.56 in the nivolumab group compared with the placebo group. Therapy-associated adverse events of any degree led to treatment discontinuation in 62% of patients in the nivolumab/ipilimumab group and in 13% of study participants receiving nivolumab treatment [13].

Based on these results, patients with stage IV malignant melanoma without evidence of disease should receive adjuvant combined immunotherapy after surgery or radiotherapy regardless of BRAFV600 mutation status. For patients with contraindications to combined immunotherapy with nivolumab and ipilumumab, one year of adjuvant therapy with nivolumab as monotherapy should be given in this situation, analogous to the CheckMate 238 trial. This therapy has a more controllable toxicity profile and is approved for the treatment of patients with completely resected stage IV disease [10].

Adjuvant immunotherapy in stages IIB and IIC

Patients with a resected melanoma and a tumor thickness according to Breslow of >4 mm or >2 mm in the presence of ulceration without lymph node involvement (stage IIB or IIC according to AJCC 8th edition) are at increased risk of recurrence. The risk of recurrence and mortality is comparable to that of patients with stage IIIA or IIIB melanoma. Data from the randomized Phase III Keynote-716 trial were presented at the ESMO 2021 Congress. These show a significant improvement in relapse-free survival with 12 months of adjuvant treatment with the anti-PD1 antibody pembrolizumab compared with placebo (HR 0.65) in patients with completely resected stage IIB or IIC melanoma. Pembrolizumab is not yet approved for this indication.

Value of adjuvant systemic therapy in stage IIIA

Prognosis in tumor stage IIIA (according to AJCC 8th edition) is very good with a survival rate of 88% at 10 years. This fact led to the debate whether adjuvant systemic therapy is overtreatment for this group of patients. Weighing the risk of severe and possibly irreversible toxicity against the potential benefit is particularly important in those patients with stage IIIA melanoma.

The CheckMate-238 trial did not include patients with AJCC stage IIIA (7th edition) melanoma [12]. In contrast, the EORTC1325/Keynote-54 trial included patients with AJCC stage IIIA (7th edition) melanoma with lymph node metastasis greater than 1 mm. In the patient subgroup with AJCC stage IIIA disease (7th edition), recurrence-free survival at one year was 89.8% with pembrolizumab therapy compared with 76.8% with placebo (HR 0.32, 99% confidence interval 0.09 -1.23; p=0.0217). After reclassification of patients using the melanoma AJCC 8th edition, 8% of patients had melanoma in tumor stage IIIA. A comparable positive effect on recurrence-free survival was observed in all subgroups. It should be noted that the follow-up time was very limited and that the confidence interval for patients with tumor stage IIIA according to AJCC 8th edition was very large [14]. The COMBI-AD study also included patients with tumor stage IIIA (AJCC 8th edition) sentinel lymph node metastases >1 mm. This study also documented a positive effect in terms of recurrence-free survival in all subgroups, but also with a less clear result for this stage [8].

Side effect profile

For adjuvant therapy of BRAFV600-mutated stage III melanoma, both the immune checkpoint inhibitors nivolumab and pembrolizumab and targeted treatment with the BRAF/MEK inhibitors dabrafenib and trametinib are available. The side effect profiles of targeted therapies and immune checkpoint inhibitors differ significantly. While reversible side effects are more common with targeted therapies, rare immune-mediated side effects can be long-lasting and irreversible with immune checkpoint inhibitors [15]. These immune-mediated side effects can affect any organ. In this context, endocrinopathies are among the most common immune-mediated side effects and, unlike the other toxicities, are usually irreversible. Accordingly, they require lifelong substitution therapy. The most common endocrine complications are dysthyroidism (30%), hypophysitides (5.6 -11%), type 1 diabetes mellitus (0.2-2%), and adrenal insufficiencies (0.7%), although rare cases of hypoparathyroidism have also been described. Furthermore, the limited data available suggest that immune-mediated primary hypogonadism due to orchitis, and secondary hypogonadism in the setting of hypophysitis, respectively, pose potential risks for subsequent infertility [16]. Half of all melanoma patients from a Danish national cohort who underwent adjuvant therapy with nivolumab discontinued the planned one-year treatment prematurely due to toxicity or relapse. Furthermore, a temporary deterioration in quality of life has been documented [17].

Therapy-associated grade 3-4 toxicities occurred in 41% of patients in the treatment arm (dabrafenib in combination with trametinib) in the COMBI-AD study, whereas this was seen in only 14% of patients in the placebo group. Pyrexia represents the most common reason for dose modification and discontinuation of targeted treatment.

Furthermore, patients often show non-specific general symptoms such as fatigue or gastrointestinal side effects in the sense of nausea. Cardiac side effects (left ventricular dysfunction, prolongation of the QT interval) occur rarely, although regular cardiac follow-up is indicated. In general, it should be noted that when adverse drug reactions occur, it is often sufficient to reduce the dose of one or both drugs. The side effects are usually completely reversible after discontinuation of the combination therapy.

Selection of adjuvant system therapy in everyday life

Very few data on toxicity and treatment discontinuation rates are available from daily practice. A Dutch study demonstrated that overall 93% of patients who qualified for adjuvant therapy received adjuvant anti-PD-1 treatment. These data showed a higher rate of toxicity with consecutive more frequent premature treatment discontinuations under treatment. Thereby, the recurrence-free survival was comparable to that in the pivotal studies [18].

For patients with BRAF wild-type melanoma, PD-1 blockade is the adjuvant therapy of choice. For patients with BRAFV600E/K-mutated melanoma, the risk of persistent immune-mediated adverse events with immunotherapy should be considered when choosing adjuvant treatment, as the hazard ratio for recurrence-free survival is comparable across the three adjuvant treatment trials. The choice of therapy must therefore be discussed with the patient and made jointly.

Take-Home Messages

- Vertical tumor thickness according to Breslow and the presence of ulceration are the most important prognostic factors.

- Molecular pathological diagnosis by next generation sequencing (NGS) to determine BRAF status should be performed from stage III onwards.

- Sentinel lymph node biopsy (SLNB) is recommended for a pT1b (i.e., Breslow tumor thickness of >0.8 mm or <0.8 mm with ulceration) stage according to AJCC 8th edition. Lymph node dissection is indicated for macroscopic lymph node involvement but is not recommended for a positive sentinel lymph node.

- Adjuvant systemic therapy with an anti-PD-1 monoclonal antibody or BRAF/MEK inhibitors is recommended starting in stage IIIA with sentinel lymph node metastasis >1 mm.

- The choice of adjuvant systemic therapy is based on the indication as well as the approval, taking into account BRAF mutation status and side effect profile.

Literature:

- Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A: Cancer statistics, 2018. A Cancer Journal for Clinicians 2018; 68(1): 7-30.

- Akbani R, et al: Genomic Classification of Cutaneous Melanoma. Cell 2015; 161(7): 1681-1696.

- Hayes AJ, et al: Wide versus narrow excision margins for high-risk, primary cutaneous melanomas: long-term follow-up of survival in a randomised trial. The Lancet Oncology 2016; 17(2): 184-192.

- Morton DL, et al: Final Trial Report of Sentinel-Node Biopsy versus Nodal Observation in Melanoma. New England Journal of Medicine 2014; 370(7): 599-609.

- Leiter U, et al: Final Analysis of DeCOG-SLT Trial: No Survival Benefit for Complete Lymph Node Dissection in Patients With Melanoma With Positive Sentinel Node. J Clin Oncol 2019; 37(32): 3000-3008.

- Faries MB, et al: Completion Dissection or Observation for Sentinel-Node Metastasis in Melanoma. N Engl J Med 2017; 376(23): 2211-2222.

- Michielin O, et al: Cutaneous melanoma: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-updagger. Ann Oncol 2019; 30(12): 1884-1901.

- Dummer R, et al: Five-Year Analysis of Adjuvant Dabrafenib plus Trametinib in Stage III Melanoma. N Engl J Med 2020; 383(12): 1139-1148.

- Eggermont AMM, et al: Adjuvant pembrolizumab versus placebo in resected stage III melanoma (EORTC 1325-MG/KEYNOTE-054): distant metastasis-free survival results from a double-blind, randomised, controlled, phase 3 trial. The Lancet Oncology 2021; 22(5): 643-654.

- Ascierto PA, et al: Adjuvant nivolumab versus ipilimumab in resected stage IIIB-C and stage IV melanoma (CheckMate 238): 4-year results from a multicentre, double-blind, randomised, controlled, phase 3 trial. The Lancet Oncology. 2020. 21(11): 1465-1477.

- Long GV, et al: Adjuvant dabrafenib plus trametinib in stage IIIBRAF-mutated melanoma. New England Journal of Medicine 2017; 377(19): 1813-1823.

- Weber J, et al: Adjuvant nivolumab versus ipilimumab in resected stage III or IV melanoma. New England Journal of Medicine 2017; 377(19): 1824-1835.

- Zimmer L, et al: Adjuvant nivolumab plus ipilimumab or nivolumab monotherapy versus placebo in patients with resected stage IV melanoma with no evidence of disease (IMMUNED): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 2 trial. The Lancet 2020; 395(10236): 1558-1568.

- Eggermont AMM, et al: Prognostic and predictive value of AJCC-8 staging in the phase III EORTC1325/KEYNOTE-054 trial of pembrolizumab vs placebo in resected high-risk stage III melanoma. European Journal of Cancer 2019; 116: 148-157.

- Ghisoni E, et al: Late-onset and long-lasting immune-related adverse events from immune checkpoint inhibitors: An overlooked aspect in immunotherapy. Eur J Cancer. 2021. 149: 153-164.

- Ozdemir BC: Immune checkpoint inhibitor-related hypogonadism and infertility: a neglected issue in immuno-oncology. J Immunother Cancer 2021; 9(2).

- Ellebaek EEA: A nationwide, real-life study of outcome and quality of life after the introduction of adjuvant immunotherapy for Danish melanoma patients. ESMO Abstract 1071P, 2021.

- De Meza MEA: Adjuvant treatment for melanoma in clinical practice: trial versus reality. ESMO Abstract 1070P, 2021.

DERMATOLOGIE PRAXIS 2022; 32(1): 11-16