Balanitis is a common problem and represents a significant limitation for the affected patient. Often, the findings are not limited to the glans, but also spread to the prepuce or its inner leaf, so that we then speak of balanoposthitis. In addition to infectious etiologies, inflammatory dermatoses must be considered. Premalignant changes may pose difficulties in the differential diagnostic differentiation from purely inflammatory lesions. The following article reviews the most important infections, inflammatory dermatoses, and premalignant changes in the glans area.

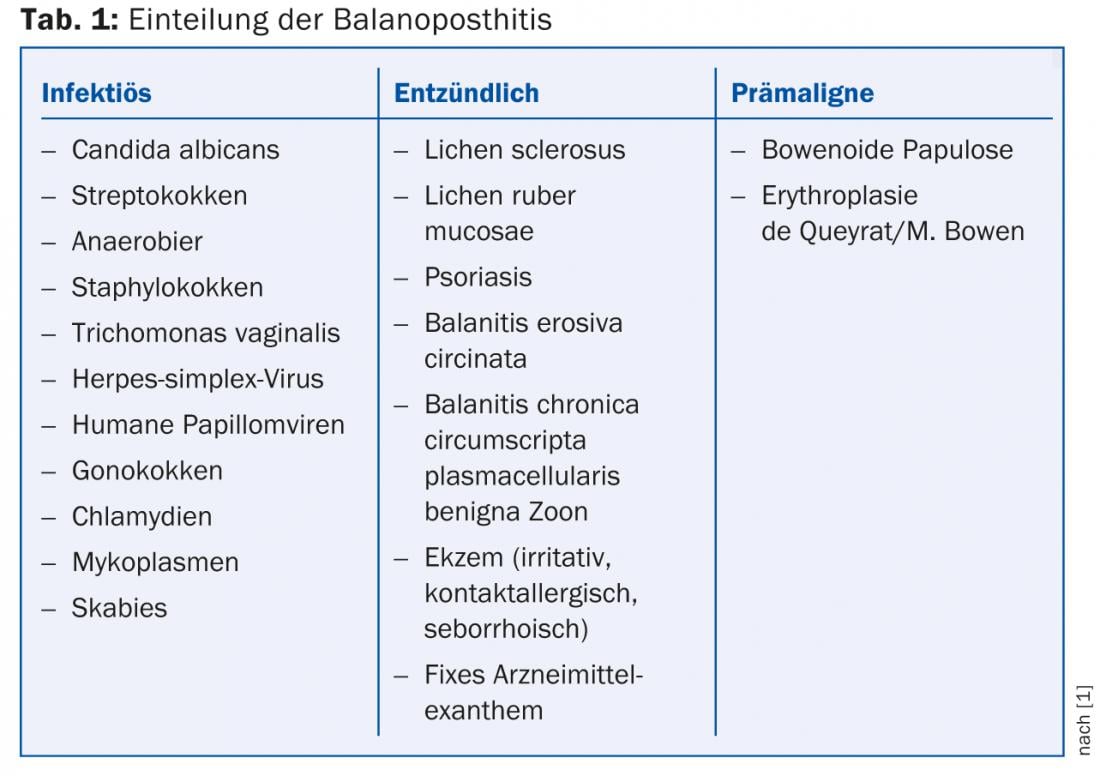

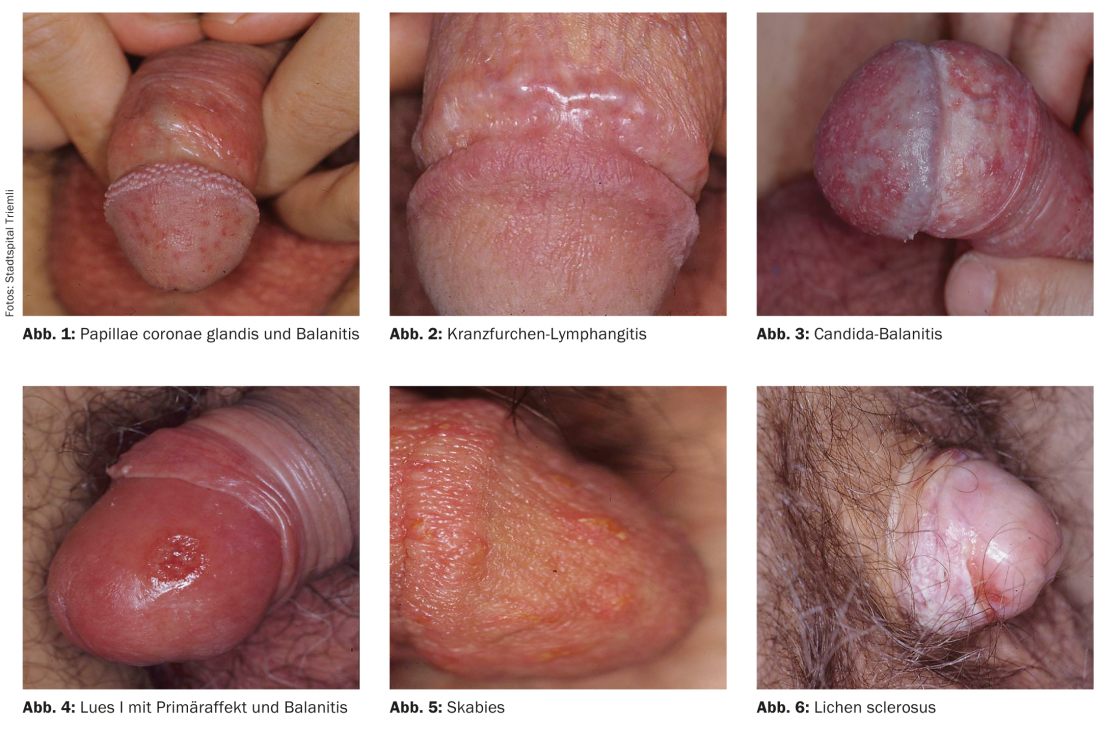

A classification of balanoposthitis is shown in Table 1, from which those patients must be distinguished who do not have balanitis in the actual sense but, for example, harmless anatomical norm variants such as the papillae coronae glandis (Fig. 1) or inflammation of structures other than the skin, as in coronary furrow lymphangitis/phlebitis (Fig. 2) .

Infectious balanitis

The often moist praeputial space may favor the growth of mycotic and bacterial pathogens. In addition, however, other factors can have a favorable effect. Thus, diabetes should also be considered in cases of candidabalanitis (Fig. 3). Conversely, Candida infestation of the glans in known diabetes mellitus can be interpreted as an indication of inadequately controlled or derailed blood glucose.

In addition to yeasts, bacteria, especially streptococci, anaerobes and staphylococci, can be the cause of balanitis.

Pathogens of sexually transmitted infections can also cause balanoposthitis. Thus, gonococci, chlamydia and mycoplasma as urethritic pathogens can cause concomitant balanitis. A less commonly considered cause of balanitis is Trichomonas vaginalis. Infections with the herpes simplex virus and human papillomaviruses have a clinical spectrum that, in addition to the typical clinic of grouped vesuculae/erosions resp. papillomatous protrusions also includes balanitis. Lues as a chameleon in dermatology can also manifest itself with balanitis (Fig. 4). Last but not least, scabies as a parasitosis can also lead to typical inflammatory changes in the glans (Fig. 5) or in the genital area. The seminal symptom here is usually the marked pruritus, especially at night, but the lesions on the glans are almost pathognomonic and usually also yield positive direct preparations.

Inflammatory dermatoses on the glans

Lichen sclerosus (“white spot disease”) is an inflammatory dermatosis of unclear, possibly autoimmune pathogenesis. In addition to subjective symptoms such as itching and dyspareunia, there is whitish discoloration and sclerosis, often with secondary phimosis or even meatus stenosis. Hemorrhages in the sclerosed areas are a typical clinical sign (Fig. 6). Highly potent local steroids (class IV) are used therapeutically. Because lichen sclerosus is a facultative precancerous condition, regular follow-up should be performed.

Lichen ruber can typically manifest in the mucosal and genital areas. As with the rest of the integument, complete inspection of which can provide valuable clues in this diagnosis, there is a clinical spectrum ranging from a whitish reticular pattern to polygonal papules to anular plaques (Fig. 7) . The livid aspect of the lesions may be diagnostic. Therapy is based on the overall picture, with topical steroids also primarily used in the genital area.

Psoriatic plaques can be observed on the glans as on the rest of the skin. Joint pain, ocular symptoms, and erosive garland-shaped foci on the glans should lead to a tentative diagnosis of balanitis erosiva circinata. STI incl. HIV should be sought and enteritis ruled out as a cause.

Eczema, whether irritant, contact allergic or seborrheic, may also manifest itself sometimes or – depending on the contact – exclusively on the glans and prepuce. In addition to a precise anamnesis with regard to the topical agents used, the patient’s own therapy should also be questioned with regard to its tolerability in the area of the genital mucosa. For example, topical preparations containing hexamidine on the glans can lead to pronounced toxic reactions (Fig. 8) and are therefore contraindicated. However, systemic medications can also typically result in a picture of fixed drug exanthema with livid macules, bullae, or erosions in the genital area. NSAIDs, tetracyclines, and barbiturates are examples of triggers, although it is often only repeated episodes manifesting at the same (fixed) site that lead to diagnosis.

Balanitis chronica circumscripta plasmacellularis benigna – often referred to as Balanitis Zoon only after the first describer because of the length of the name – is treated primarily with disinfection and drying as a benign inflammatory dermatosis, probably caused by irritation. If this is not sufficient, circumcision may be considered.

Premalignant changes of the glans

Finally, precancerous lesions must be differentially diagnosed, which, strictly speaking, are no longer balanitis, i.e. a purely inflammatory change. In addition to Bowenoid papulosis, which is usually easily recognized due to its brown papules and flat plaques, it is erythroplasia de Queyrat/Bowen’s disease of the glans that is often only recognized as a precancerous condition due to the lack of evidence of the pathogen and, above all, due to its resistance to therapy. Early histologic confirmation and therapy are essential to prevent progression to penile carcinoma (Fig. 9).

Diagnostics

In addition to infectious diagnostics, which should include swabs for bacteriological and mycological diagnostics as well as STI screening, a biopsy should be considered, especially in cases of frequent recurrences or resistance to therapy.

Therapy

If a pathogen is detected, it is treated accordingly. If improvement fails to occur, a trial of metronidazole may be attempted empirically. Care must always be taken to maintain a balance in hygiene, which means improving it in some patients while discouraging others from too frequent washing with soap. In the absence of evidence of pathogens, good hygiene, and lack of improvement despite care with emollients, topical use of a class I steroid such as hydrocortisone for two weeks may be considered. If this also fails to improve, referral to a dermatologist and/or biopsy is indicated.

Literature:

- IUSTI 2012 European guideline for the management of balanoposthitis.

- English JC, et al: Dermatoses of the glans penis and prepuce. J Am Acad Dermatol 1997; 37: 1-24.

- Singh S, Bunker C: Male genital dermatoses in old age. Age and Aging 2008; 37: 500-504.

- Teichman JMH, et al: Noninfectious penile lesions. American Family Physician 2010; 81: 167-174.

- Fistarol SK, Itin PH: Diagnosis and treatment of lichen sclerosus. An update. Am J Clin Dermatol 2013; 14: 27-47.

DERMATOLOGIE PRAXIS 2013; 23(6): 4-6