Good analgesia is necessary in acute otitis media. Whether the administration of antibiotics is indicated must be decided on the basis of the age and severity of the disease, among other factors. With “watchful waiting,” you don’t risk an increased complication rate.

Acute otitis media (AOM) is an acute infection of the middle ear caused by viruses and/or bacteria with purulent or non-purulent secretions in the middle ear. It can occur at any age, but is most common in children between six and 24 months. It is one of the most common childhood illnesses that involve a visit to the doctor and the prescription of antibiotics. More than two-thirds of all children have suffered at least one episode of AOM by the end of the third year of life, and about half of children have suffered three or more episodes [1].

The most common bacterial organisms causing AOM are Streptococcus pneumoniae, followed by Haemophilus influenzae and Moraxella catarrhalis. The pneumococcal strains included in the vaccine have become less common as causative agents of AOM since the introduction of pneumococcal vaccination. The most common viral pathogens are respiratory syncytial virus (RSV), coronavirus, influenza virus, adenovirus, human metapneumovirus, and picornavirus.

Diagnosis is particularly challenging in low-cooperating young children. The frequent occurrence of AOM in infants and young children has several reasons: On the one hand, the function of Eustach’s tube is less efficient at this age for anatomical reasons, and on the other hand, there is immaturity of the immune system. Risk factors for AOM include male gender, genetic predisposition, exposure to pathogenic germs through siblings or in the crib, low socioeconomic status, smoking exposure, and lack of breastfeeding [2].

Symptoms and diagnostics

Older children and adults commonly report rapid onset ear pain. In young children, touching or manipulating the auricles may be suggestive of ear pain. Furthermore, parents describe strong crying, fever, restless sleep or changed behavior during the day, all in all relatively unspecific symptoms. Often, the symptoms are preceded by an upper respiratory tract infection.

The American Academy of Pediatrics [3] and American Academy of Family Physicians guidelines, last revised in 2013, list the following diagnostic criteria:

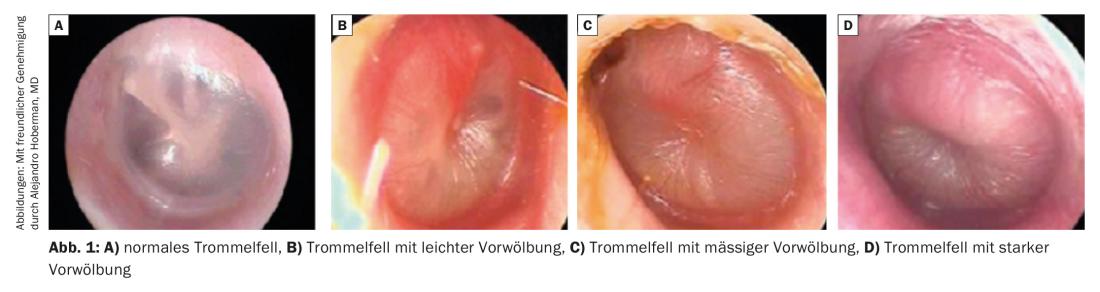

- Moderate to severe protrusion of the eardrum or

- New-onset otorrhea not caused by otitis externa; or

- Mild protrusion of the eardrum and acute onset of ear pain (less than 48 hours) or severe redness of the eardrum.

The diagnosis of AOM should not be made in the absence of middle ear effusion (on pneumatic otoscopy or tympanometry) (Fig. 1).

Occasional cleaning is necessary to evaluate the ear. The ear canal should not be cleaned by ear irrigation during a suspected infection, but through the otoscope with an eyelet. In young children, otoscopy may be difficult or impossible due to lack of cooperation and resistance. In general, it is often difficult to distinguish otoscopically AOM from chronic tympanic effusion.

To rule out an otogenic complication, inspection and palpation of the mastoid and assessment of facial nerve function are useful. In older children and adults, an orienting hearing test with tuning fork test according to Weber and Rinne should be performed to exclude inner ear involvement.

AOM can lead to spontaneous perforation of the tympanic membrane and ear flow. In these cases, AOM must be distinguished from otitis externa, an inflammation of the external auditory canal in which ear discharge also occurs. However, the auricle and the auditory canal are sensitive to pain when touched. Differential diagnosis of otorrhea may also include superinfection with preexisting tympanic membrane perforation. These episodes are not painful, do not require systemic antibiotic therapy, and respond well to ciprofloxacin ear drops.

Treatment

Initial therapy for uncomplicated AOM in the otherwise healthy patient includes good analgesic therapy with an NSAID and/or acetaminophen. Antibiotic therapy is not indicated in every case, since the infection has a high spontaneous healing rate and no increased complication rate has been observed with “watchful waiting”. Restrictive use of antibiotics can also prevent antibiotic-associated complications such as diarrhea, vomiting, or rash [4]. Patients must be re-evaluated after 48 to 72 hours. In the absence of improvement under analgesics, antibiotic therapy should be established. Placebo-controlled studies have shown that spontaneous improvement of symptoms of AOM occurs in 60% within the first 24 hours and in 84% within the first two to three days [4].

The age and severity of the disease must be taken into account when deciding whether antibiotics are indicated in addition to analgesic therapy [3,4]. The fewer the symptoms (no or low fever, no otalgia, no otorrhea, only one ear affected), the more likely AOM will resolve without antibiotics.

Antibiotic therapy is indicated in any case in the following situations:

- Age <6 months

- Age <2 years for bilateral AOM.

- Persistent purulent otorrhea

- Poor general condition

- Only hearing ear affected

- Risk factors (e.g., immunodeficiency, severe underlying diseases, Down syndrome, craniofacial anomalies, cochlear implant users).

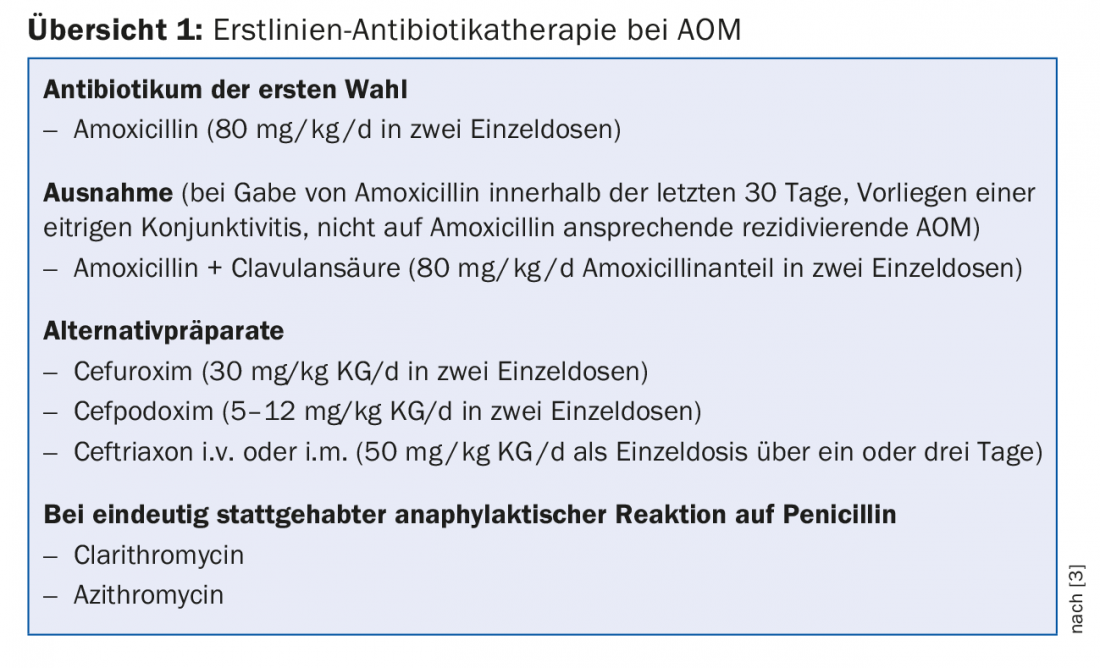

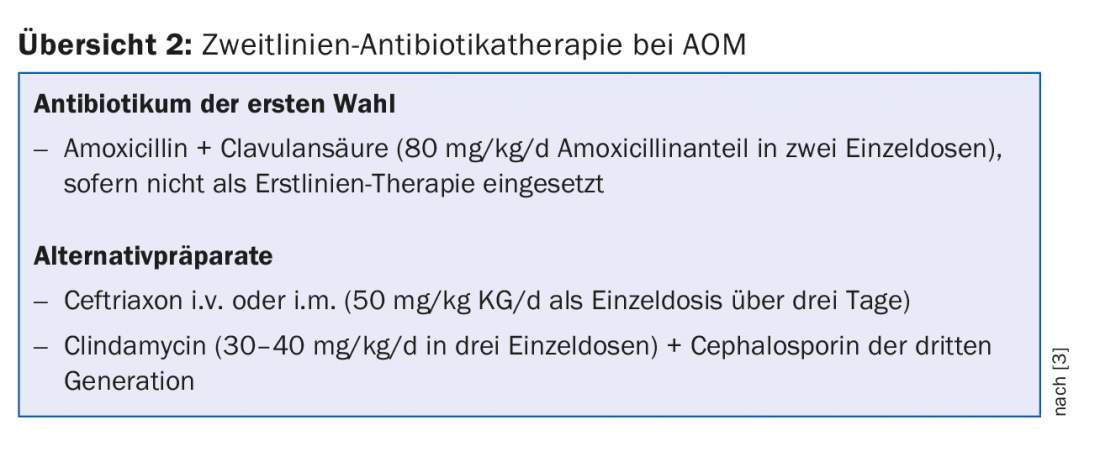

The antibiotic of first choice is amoxicillin (80 mg/kg/d in two single doses). Amoxicillin plus clavulanic acid (80 mg/kg/d of amoxicillin in two single doses) is recommended if therapy with amoxicillin has occurred within the last 30 days, additional purulent conjunctivitis is present, or if there is a history of recurrent AOM unresponsive to amoxicillin. Alternative preparations are cefuroxime, cefpodoxime, ceftriaxone (i.m. or i.v.). In cases of true penicillin allergy, clarithromycin and azithromycin may be considered, although macrolides have limited effect on H. influenzae and S. pneumoniae. Amoxicillin with clavulanic acid should be used as a second-line antibiotic in the absence of a response after 48 to 72 hours and if not already used as first-line therapy; ceftriaxone (i.m. or i.v.) or clindamycin in combination with a third-generation cephalosporin should be used in cases of penicillin allergy (review 1 and 2) [3].

With regard to the duration of therapy, antibiotic therapy for ten days is recommended in children up to the end of the second year of life and in children with severe disease, and for seven days in children from the third to the sixth year of life and for five to seven days from the sixth year of life [3].

Intravenous antibiotic administration is indicated for treatment failure of amoxicillin plus clavulanic acid or second-line therapy. If intravenous treatment also does not lead to any improvement or if repeated infections occur within a short period of time, a paracentesis and a smear of middle ear secretions as well as a resistance-appropriate switch to another antibiotic class are necessary due to a possible development of resistance.

Evidence for the benefit of topical local anesthetics is limited and administration is therefore not recommended. Decongestant medications (tablets or nasal drops), steroids, or antihistamines also have no place in the treatment of AOM and should not be prescribed. At best, they are indicated in the presence of concomitant rhinitis [5]. Also due to the limited data available, no generally valid recommendations exist to date for preventive medication with, for example, prebiotics/probiotics, vitamin D or xylitol [5,6].

Tympanostomy tube insertion may be useful as therapy for recurrent AOM. This is defined by at least three episodes of AOM in six months or at least four episodes in twelve months.

Complications

Since the availability of antibiotics, complications of AOM are much less common. A possible complication of AOM is spontaneous perforation of the tympanic membrane due to pressure building up in the middle ear. Purulent secretions are discharged, often resulting in prompt reduction of pain. Additional therapy with ciprofloxacin drops is useful in this case. The perforation usually heals spontaneously, but it may rarely persist. Therefore, a perforation should be monitored otoscopically until it heals and water conservation should be practiced. Rarely, AOM results in arrosion of the ossicles, usually the long process of the incus, with consecutive conductive hearing loss.

AOM always results in mucosal involvement in the mastoid cells. Acute mastoiditis as a complication is present with abscess formation and/or destruction of osseous structures. The clinically classic signs consist of a retroauricular doughy swelling and a protruding ear. The complications of mastoiditis are usually intracranial and severe. An epidural or brain abscess may occur. Further, septic thrombosis of the sigmoid sinus may develop with repeated episodes of fever. Furthermore, development of labyrinthitis with vertigo and nystagmus and/or sensorineural hearing loss or facial nerve palsy due to inflammatory co-reaction of the nerve may occur. A serious complication is also the development of meningitis by hematogenous spread.

When is referral to a specialist appropriate?

Referral to an ENT specialist is indicated in cases of uncertainty in diagnosis, lack of response to antibiotic therapy, and a complicated course. Especially when the question of invasive therapy arises, an ENT specialist evaluation is helpful.

Take-Home Messages

- Good analgesic therapy is necessary in acute otitis media (AOM).

- The age and severity of the disease must be considered in the decision-making process as to whether the administration of antibiotics is indicated.

- Spontaneous improvement of symptoms of AOM occurs in 60% within the first 24 hours, and in 84% within the first two to three days.

- No increased complication rate was observed with “watchful waiting”.

Literature:

- Teele DW, et al: Epidemiology of otitis media during the first seven years of life in children in greater Boston: a prospective, cohort study. J Infect Dis 1989; 160(1): 83-94.

- Granath A: Recurrent Acute Otitis Media: What Are the Options for Treatment and Prevention? Curr Otorhinolaryngol Rep 2017; 5(2): 93-100.

- Lieberthal AS, et al: The diagnosis and management of acute otitis media. Pediatrics 2013; 131(3): e964-999.

- Venekamp RP, et al: Antibiotics for acute otitis media in children. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2015; 6: CD000219.

- Schilder AG, et al: Otitis media. Nat Rev Dis Primers 2016 Sep 8; 2: 16063.

- Marom T, et al: Complementary and Alternative Medicine Treatment Options for Otitis Media: A Systematic Review. Medicine (Baltimore) 2016; 95(6): e2695.

HAUSARZT PRAXIS 2018; 13(5): 32-35