Arrhythmias are one of the most common cardiac complications during pregnancy in women with and without known structural heart disease. Arrhythmias that were previously infrequent may become more frequent during pregnancy or may occur for the first time ever. A comprehensive overview of cardiac handling in pregnancy.

Arrhythmias are one of the most common cardiac complications during pregnancy in women with and without known structural heart disease. Previously infrequent arrhythmias may become much more common during pregnancy or may occur for the first time ever during pregnancy [1].

The accumulation of arrhythmias during pregnancy occurs as a result of altered hemodynamics, hormonal status and changes in the autonomic nervous system. Atrium and ventricle increase in volume. The preload increases and the additional wall tension in both the atrium and ventricle may lead to increased arrhythmogenicity. In addition, resting rate is often elevated and heart rate variability is reduced.

Bradycardias

Normally, the frequency of sinus rhythm increases by 10-20 beats/min during pregnancy. Sinus bradycardia is therefore a relatively rare occurrence. During the night or during vagal reactions, which are often observed during birth, but also more frequently in the first days after birth, sinus bradycardia or 1st or even 2nd degree AV block of Wenckebach type may occur, which is usually harmless.

However, should type II, type Mobitz, or third-degree AV block be observed, there is often an association with structural heart disease.

Congenital total AV block is sometimes completely asymptomatic and is only noticed during pregnancy. On ECG, there is a sufficient replacement rhythm with narrow QRS complex. However, in a study of women with asymptomatic congenital AV block, syncope as well as complications occurred in 13% of pregnancies and some women then required pacemaker implantation [2]. For this reason, in the case of preexisting higher-grade AV block, pacemaker implantation should be evaluated before pregnancy. During pregnancy, this is still possible, but not desirable due to x-ray exposure.

Supraventricular tachycardias

Supraventricular extrasystoles are very common during pregnancy. Occasionally, they may cause severely disruptive palpitations, but most often these extrasystoles do not cause discomfort.

The most common arrhythmias in women during pregnancy are paroxysmal supraventricular tachycardias, most commonly caused by AV nodal reentry or AV reentry tachycardias via accessory pathways. The incidence has been estimated at 24/100,000 hospitalizations of pregnant women [3]. Supraventricular tachycardias either occur for the first time during pregnancy or are suddenly much more common and result in more severe symptoms [1]. The symptomatology is no different than outside of pregnancy with palpitations, dyspnea, presyncope, chest pain, and severe anxiety. The sudden onset and sudden termination of tachycardia are classic.

For therapy of an episode of supraventricular tachycardia, vagal maneuvers (Valsalva, carotid sinus massage, sip of cold water) may be tried or intravenous adenosine. If tachycardia is very poorly tolerated, direct electroconversion may be considered at best. Since adenosine has a very short half-life, only very reduced exposure occurs in the child. Possible other pharmacological agents include beta-blockers (propranolol or metoprolol). A beta-blocker may also be considered as prophylactic pharmacological therapy to prevent an episode of supraventricular tachycardia. However, prolonged use carries a risk of intrauterine growth restriction in the child [4].

In the case of severe supraventricular tachycardia, electrophysiologic testing and catheter ablation should be performed before pregnancy, if possible. Catheter ablation during pregnancy is also theoretically possible. The use of three-dimensional electroanatomical maps and a special positioning system largely eliminates the need for X-rays.

Atrial fibrillation and flutter

These arrhythmias are less common during pregnancy. However, in the presence of preexisting structural heart disease or additional comorbidities, both atrial fibrillation and atrial flutter may increase, e.g., in rheumatic heart disease, valvular disease, or hypertrophic cardiomyopathy in addition to known peripartum cardiomyopathy or congenital heart disease. As in non-pregnant women, the spectrum of symptomatology is very broad, ranging from completely asymptomatic to severely disruptive and hemodynamically relevant.

Pregnant women with atrial fibrillation should be thoroughly evaluated. If an additional factor (thyroid disease, alcohol consumption, inflammation) is found, it must be treated as a priority.

In addition, atrial fibrillation and atrial flutter are associated with an increased risk of thromboembolic events. Although most pregnant women have a CHA2DS2-VASc risk score of 1, pregnancy itself already leads to a prothrombotic state and therefore probably to an increased thromboembolic risk.

Unfractionated or low-molecular-weight heparin is available to protect against thromboembolic complications. Marcoumar® and Sintrom® should not be used or should only be used from the second trimester and only up to one month before birth due to the potential teratogenicity of these substances. The new oral anticoagulants are also not recommended because some of them have fetotoxic effects.

Because most patients have a low CHA2DS2-VASc risk score, anticoagulation can often be omitted [5].

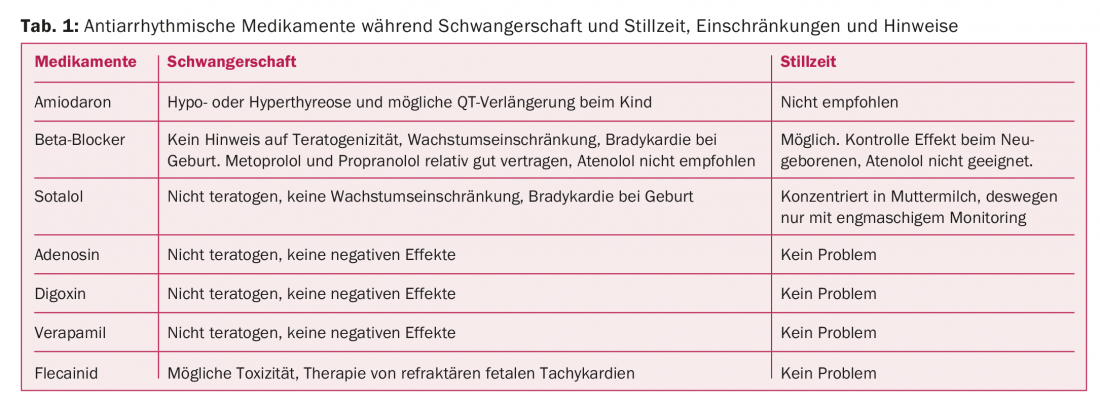

Beta-blockers, digoxin, or calcium channel antagonists may be considered for frequency control of atrial fibrillation. Antiarrhythmic medications or electroconversion may be considered for rhythm control. A possible teratogenic effect of antiarrhythmic substances would come into effect mainly in the first trimester. In the second and third trimesters, there is an increased risk of impeding fetal growth and further development. During delivery, there is a risk of some proarrhythmogenicity and an effect on uterine contractility. An overview of side effects of antiarrhythmic drugs during pregnancy and lactation is shown in Table 1.

Electrical cardioversion can be performed throughout pregnancy. The risk of electroconversion inducing arrhythmia in the fetus is very small. However, it is recommended to monitor the fetal rhythm [6]. In the third trimester, it may be advisable to perform electroconversion under general anesthesia and intubation due to airway changes and increased risk of aspiration. Catheter ablation of atrial fibrillation or flutter is possible, but rarely a necessity, thanks to the use of electroanatomic mapping, which greatly reduces x-ray exposure.

Ventricular tachycardia

Pregnant women with known arrhythmias or known structural heart disease have the highest risk of also developing arrhythmias during pregnancy. The number of women with congenital heart disease who become pregnant is increasing, and with them the risk for malignant arrhythmias during pregnancy.

Palpitations and ventricular extrasystoles are common during pregnancy. The extrasystoles alone are not a reason for therapy. Known promoting factors include smoking, coffee consumption, the use of alcohol and other stimulants. Your consumption should be discussed with regard to pregnancy anyway. Ventricular tachycardia or ventricular fibrillation is rare during pregnancy, but women with structural heart disease who have previously experienced ventricular tachycardia are at increased risk of also experiencing it during pregnancy (27%) [7]. Known cardiac diseases that lead to an increased risk of ventricular tachycardia include hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, peripartum cardiomyopathy, arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy, and congenital heart disease and valvular disease. Myocardial infarctions with and without coronary artery disease have been observed during pregnancy and may also result in ventricular tachycardia or fibrillation. Likewise, risk factors include long-QT or Brugada syndrome, as well as electrolyte disturbances, hypertensive crises, or thyrotoxic crises.

Patients with long-QT syndrome have relative protection in pregnancy because resting heart rate is increased, decreasing the likelihood of torsade de pointes ventricular tachycardia. However, the reduction in heart rate postpartum and the added stress while caring for the newborn with sleep deprivation may again increase the risk of arrhythmias [8]. Beta-blockers were able to reduce the risk of malignant arrhythmias in long-QT syndrome both during and after pregnancy. In hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, ventricular tachycardia and ventricular fibrillation are relatively rare. However, in the presence of severe left ventricular hypertrophy and increased pressure gradient in the left ventricular outflow tract, the risk increases. It is also relatively rare for malignant arrhythmias to occur in arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy. However, the experience is limited. Again, the use of beta-blockers is recommended.

Any ventricular tachycardia is potentially life-threatening and should be stopped as soon as possible. Electrical cardioversion is recommended. This should only be performed with fetal monitoring. The use of cardioselective beta-blockers such as metoprolol or even sotalol is possible. Amiodarone can cause serious fetal side effects and should be reserved for emergency indications in refractory arrhythmias [9]. It is important that antiarrhythmic drugs and an external defibrillator are available during delivery for pregnant women at increased risk for ventricular tachycardia.

Women with an implanted ICD can have a problem-free pregnancy. No clustering of complications or ICD therapies has been observed during pregnancy compared with before pregnancy [10]. Experience with ablation of ventricular tachycardia during pregnancy is very limited. However, catheter ablation could be attempted in the case of malignant and unmanageable arrhythmias, again by using three-dimensional electroanatomic mapping systems to minimize radiation exposure.

Take-Home Messages

- Arrhythmias are the most common cardiac complication during pregnancy. They are often associated with structural heart disease. Any pregnant woman who has arrhythmias should have a thorough cardiologic evaluation, including. ECG and transthoracic echocardiogram.

- Most common arrhythmias in women without structural heart disease are supraventricular tachycardias.

- Beta-blockers (metoprolol or propranolol), digoxin, or verapamil are considered relatively safe.

- Acute therapy for sustained ventricular tachycardia is electroconversion.

- Sinus bradycardia may exist transiently for a few days after a normal birth.

- Higher-grade AV block is often associated with structural heart disease.

- The indication for pacemaker therapy is unchanged from the normal population.

Literature:

- Regitz-Zagrosek V, et al: ESC Guidelines on the management of cardiovascular diseases during pregnancy: the Task Force on the Management of Cardiovascular Diseases during Pregnancy of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Eur Heart J 2011 Dec; 32(24): 3147-3197.

- Michaëlsson M, et al: Isolated congenital complete atrioventricular block in adult life. A prospective study. Circulation 1995; 92(3): 442-449.

- Li JM, et al: Frequency and outcome of arrhythmias complicating admission during pregnancy: experience from a high-volume and ethnically-diverse obstetric service. Clin Cardiol 2008; 31(11): 538-541.

- Page RL, et al: 2015 ACC/AHA/HRS Guideline for the Management of Adult Patients With Supraventricular Tachycardia: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines and the Heart Rhythm Society. J Am Coll Cardiol 2016; 67(13): e27-e115.

- Kirchof P, et al: 2016 ESC Guidelines for the management of atrial fibrillation developed in collaboration with EACTS. Europace 2016; 18(11): 1609-1678.

- Wang YC, et al: The impact of maternal cardioversion on fetal haemodynamics. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 2006; 126(2): 268-269.

- Silversides CK: Recurrence rates of arrhythmias during pregnancy in women with previous tachyarrhythmia and impact on fetal and neonatal outcomes. Am J Cardiol 2006; 97(8): 1206-1212.

- Rashba EJ, et al: Influence of pregnancy on the risk for cardiac events in patients with hereditary long QT syndrome. LQTS Investigators. Circulation 1998; 97(5): 451-456.

- Bartalena L, et al: Effects of amiodarone administration during pregnancy on neonatal thyroid function and subsequent neurodevelopment. J Endocrinol Invest 2001; 24: 116-130.

- Natale A, et al: Implantable cardioverter-defibrillators and pregnancy: a safe combination? Circulation 1997; 96(9): 2808-2812.

CARDIOVASC 2018; 17(3): 4-6