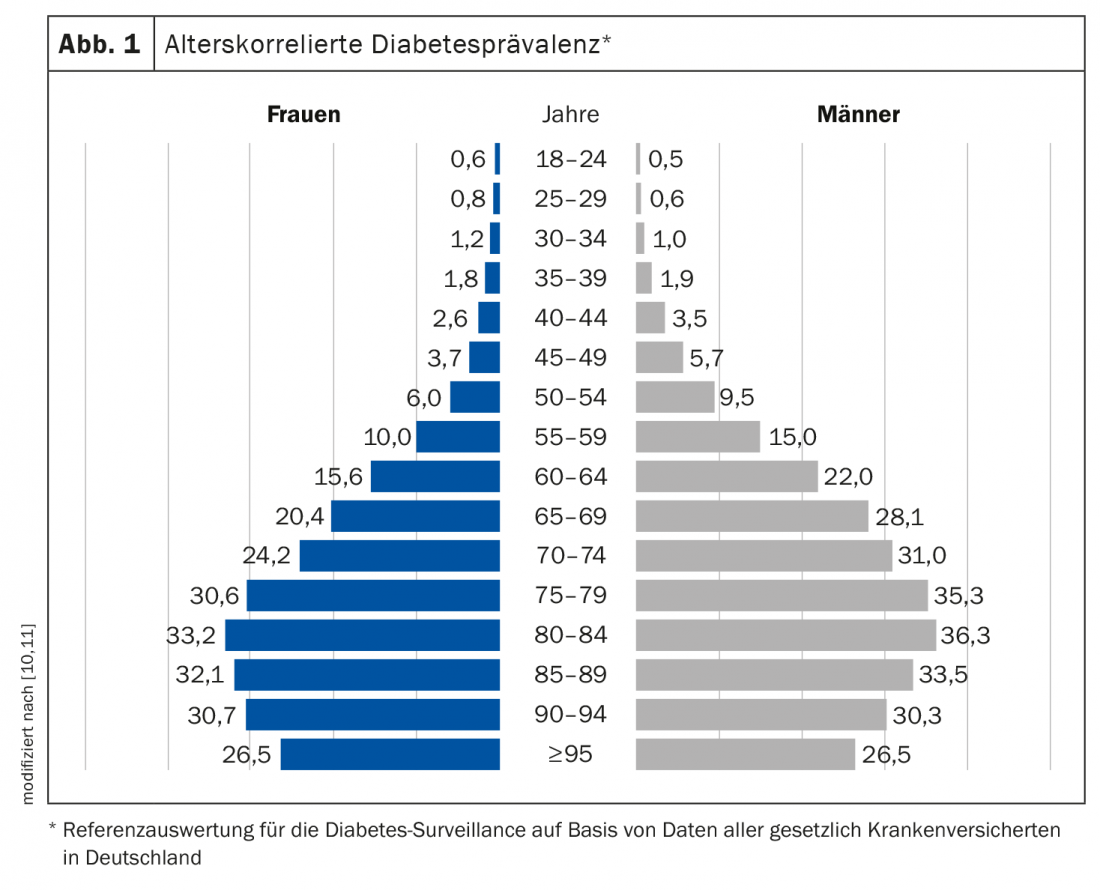

Over the past three decades, global diabetes prevalence has steadily increased, with an age-correlated increase in prevalence. Therapeutic goals in older type 2 diabetic patients differ from those of younger patients. For example, the avoidance of hypoglycemia has a higher priority and the inclusion of individual patient characteristics and comorbidities is of particular importance.

Prevalence rates for drug-treated diabetes in people over 60 years of age in Switzerland were 11.0% for men and 4.7% for women in a population-based study [1,2]. According to data from the Global Burden of Disease study, diabetes-related mortality in Switzerland has been declining over the last three decades [2]. Individualized diabetes therapy can reduce the risk of diabetic complications or delay their manifestation. Diabetes mellitus type 2 is a multifactorial disease that is primarily promoted by chronic malnutrition, lack of exercise, and resulting overweight (BMI ≥25 kg/m2) or obesity (BMI ≥30 kg/m2). However, not all overweight or obese individuals necessarily develop diabetes, but only if there is a genetic predisposition. Currently, over 40 gene loci associated with type 2 diabetes mellitus are known, many of which are associated with impaired beta-cell function [2]. Stress, depression, burn-out, and anxiety disorders can also contribute to the development of diabetes, not only through direct negative effects on metabolism, but also via unhealthy diet, sleep problems, increased smoking, and alcohol consumption [3]. Acute complications in type 2 diabetes result particularly from severe hyperglycemia or hypoglycemia [4]. The chronic complications arise primarily from prolonged disturbances in insulin and blood glucose levels. These can lead to macroangiopathy and microangiopathy [4,5]. Macroangiopathic sequelae include, for example, coronary artery disease or pAVK. Microangiopathic tissue damage includes retinopathy, nephropathy, and neuropathy.

Set HbA1c target value individually and minimize hypoglycemia risks

Whereas in younger age, diabetes therapy is often glucocentric to a target HbA1c of around 6.5-7%, in older age the priority is to avoid hypoglycemia [6]. Age-typical multimorbidity plays an important role and so do glucose-lowering drugs with added cardio- and nephroprotective benefits. The low to no risk of hypoglycemia of gliptins, SGLT-2 inhibitors, and GLP-1 analogs is very advantageous for elderly type 2 diabetics, and insulin degludec is a basal insulin that shows a stable glucose curve over day and night due to a long half-life [6,7]. According to the current treatment recommendations of the Swiss Society of Endocrinology and Diabetology (SGED), a target HbA1c value <8.0% should be aimed for in elderly patients with long duration of diabetes and advanced micro- and/or macrovascular complications. If the target value is met, HbA1c should be checked at least twice a year, otherwise quarterly.

Select appropriate method of insulin administration

Insulin pumps enable continuous baseline insulin delivery, which means that only the preprandial bolus insulin injections still need to be administered manually by syringe or pen. In addition to continuously improving insulin preparations and insulin delivery techniques, blood glucose monitoring systems have also evolved in recent years, from better point-of-care HbA1c measurement techniques, to better self-monitoring options, to minimally invasive continuous glucose sensors. The latter eliminate the need for repeated capillary blood glucose measurements, require only occasional recalibration, and can alert diabetics in real time when current or predicted glucose levels are suboptimal.

Optimize glycemic control

These advances have the potential to substantially improve glycemic control in appropriately trained and motivated diabetic patients [2]. The combination of insulin pumps with continuously measuring glucose sensors (CGM) in so-called “hybrid closed-loop insulin delivery systems” also makes manual bolus injections superfluous, as the case may be. It is hoped that in the future, semi-automated or fully automated systems will further simplify treatment and more closely mimic the role of the pancreas and beta cells (“artificial pancreas”) [8,9]. Studies with hybrid closed-loop insulin delivery systems are promising and show that they can improve nighttime glycemic control, reduce the risk of hypoglycemia, and better control glycemic fluctuations throughout the day (24 h) [8,9]. CGM or FGM (flash glucose monitoring) may be useful especially in patients with high glycemic variability and in patients on intensified insulin therapy who have no or very few blood glucose measurements [2].

Literature:

- Forni Ogna V, et al: Prevalence and determinants of chronic kidney disease in the Swiss population. Swiss Med Wkly 2016; 146: w14313

- Fürst T, Probst-Hensch N: Diabetes Mellitus. Burden of disease and care in Switzerland (Obsan Report 10/2020). Neuchâtel: Swiss Health Observatory. www.obsan.admin.ch, (last accessed 03.11.2022)

- Dendup T, et al: Environmental Risk Factors for Developing Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus: A Systematic Review. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2018; 15(1). 78. doi: 10.3390/ijerph15010078.

- Nolan CJ, Damm P, Prentki M: Type 2 diabetes across generations: from pathophysiology to prevention and management. Lancet 2011; 378(9786): 169-181.

- Chatterjee S, Khunti K, Davies MJ: Type 2 diabetes. Lancet 2017; 389(10085): 2239-2251.

- Zeyfang A: Diabetes therapy in old age (1): A special challenge. Dtsch Arztebl 2021; 118(44): [26]; DOI: 10.3238/PersDia.2021.11.05.08, www.aerzteblatt.de/archiv/221804/Diabetestherapie-im-Alter-(1)-a-special-challenge, (last accessed Nov 03, 2022).

- Sorli C, et al: Elderly patients with diabetes experience a lower rate of nocturnal hypoglycaemia with insulin degludec than with insulin glargine: a meta-analysis of phase IIIa trials. Drugs Aging 2013; 30 (12): 1009-1018.

- Garg SK, et al: Glucose Outcomes with the In-Home Use of a Hybrid Closed-Loop Insulin Delivery System in Adolescents and Adults with Type 1 Diabetes. Diabetes Technol Ther 2017; 19(3): 155-163.

- Kovatchev B. The artificial pancreas in 2017: The year of transition from research to clinical practice. Nat Rev Endocrinol 2018; 14(2): 74-76.

- Robert Koch Institute: Diabetes in Germany, National Diabetes Surveillance Report 2019, https://diabsurv.rki.de, (last accessed Nov. 03, 2022).

- Schmidt C, et al: Prevalence and incidence of documented diabetes mellitus – reference evaluation for diabetes surveillance based on data from all statutorily insured persons. Bundesgesundheitsbl 2020; 63: 93-102.

- Austrian Diabetes Association: Guidelines for Practice. Abstract: Diabetes Mellitus 2019, www.oedg.at/pdf/OEDG_Pocket_Guide_2019-07.pdf, (last accessed Nov. 03, 2022).

HAUSARZT PRAXIS 2022; 17(11): 18-20

CARDIOVASC 2022; 21(4): 36-37