Around 90% of patients with dementia diseases develop a number of behavioral and psychological disorders in addition to cognitive disorders in the course of dementia, which are described in the literature as BPSD (Behavioural and Psychological Symptoms of Dementia). The treatment of behavioral disorders has a higher priority for the affected person and their relatives than the improvement of cognitive performance abilities. It is precisely these symptoms, such as agitation, anxiety and aggressiveness, that massively impair the quality of life of dementia patients, burden and discourage family caregivers, and in many cases are responsible for earlier institutionalization.

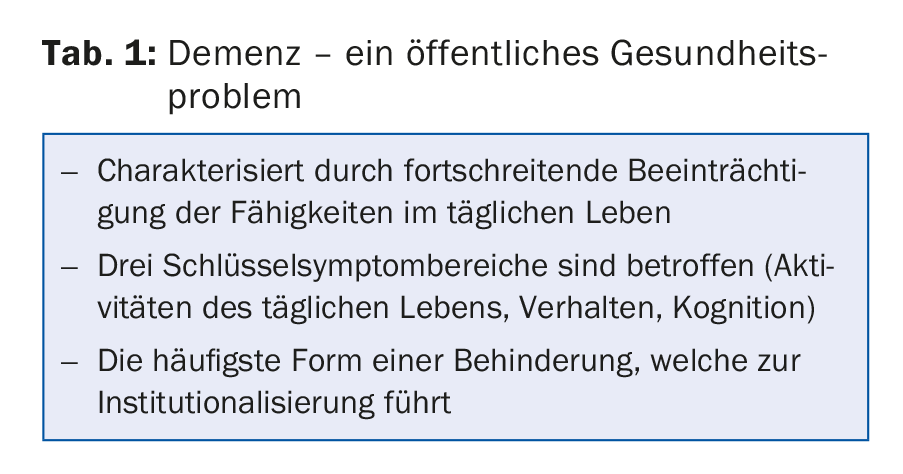

Dementia is an umbrella term for a variety of conditions. All of the approximately 55 subtypes of dementia have in common that they lead to a loss of mental capacity. The most prominent feature of this disease is memory impairment. However, we can only speak of dementia when, in addition to the memory deficit, other mental functions are affected, such as speech, purposeful action, recognition, or when planning and coping with everyday life are no longer possible. (Tab.1). These disorders must reach a level where basic activities of daily living become insurmountable obstacles for the individual (e.g., getting dressed, washing oneself, etc.). More than half of all forms of dementia can be clinically and neuropathologically classified as Alzheimer’s disease (AD).

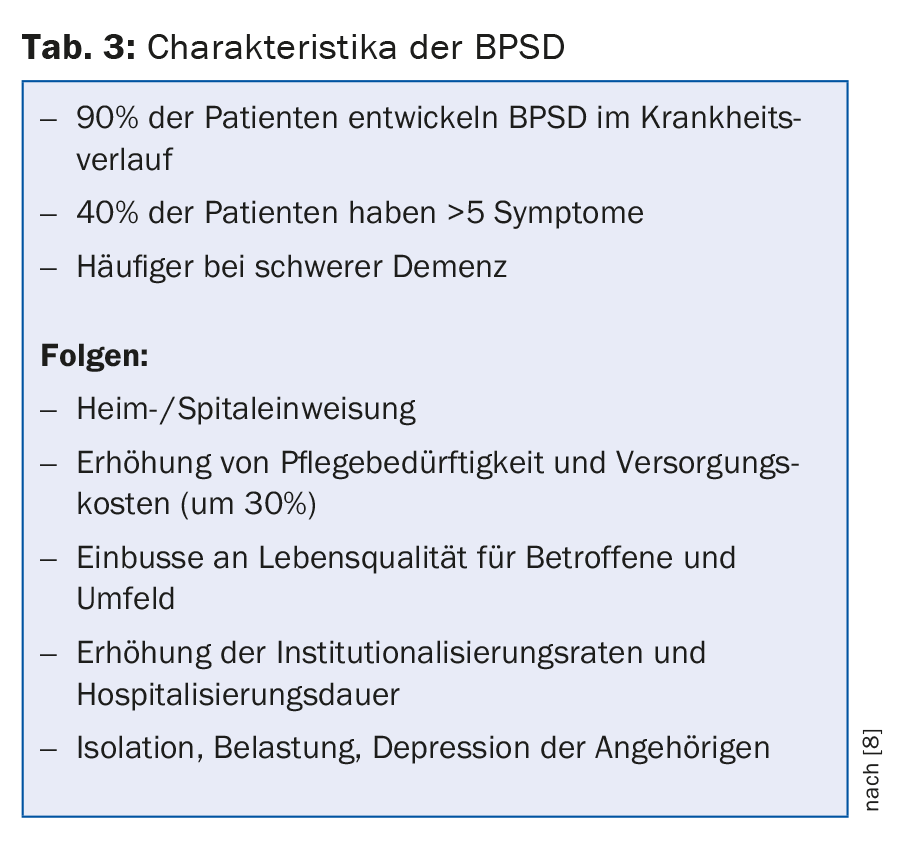

70-90% of all affected individuals develop behavioral and psychological disorders during the course of dementia [1]. The term behavioral disorders includes all non-cognitive disorders of dementia. The term “Behavioural and Psychological Symptoms of Dementia” (BPSD) has been proposed by the International Psychogeriatric Association (IPA) for these disorders in dementia. This includes in particular depressive disorders, psychotic phenomena, agitation and aggressive behavior. The frequencies found in studies are up to 80% for depression, 20-73% for delusions, 15-49% for hallucinations, and up to 20% for aggressiveness [2]. Although these disorders are the most common cause of hospital or home admission, their clinical significance is often underestimated [3]. According to Förstl, due to the common neuropathological changes, these symptoms should be considered as equivalent to cognitive impairment and not as reactive manifestations of dementia [4]. BPSD are not only the consequence of degenerative processes in the brain, but also an expression of a close interplay with psychosocial influences, the premorbid personality structure, the often existing multimorbidity and the still existing conflict management strategies.

Behavioral disorders and personality changes

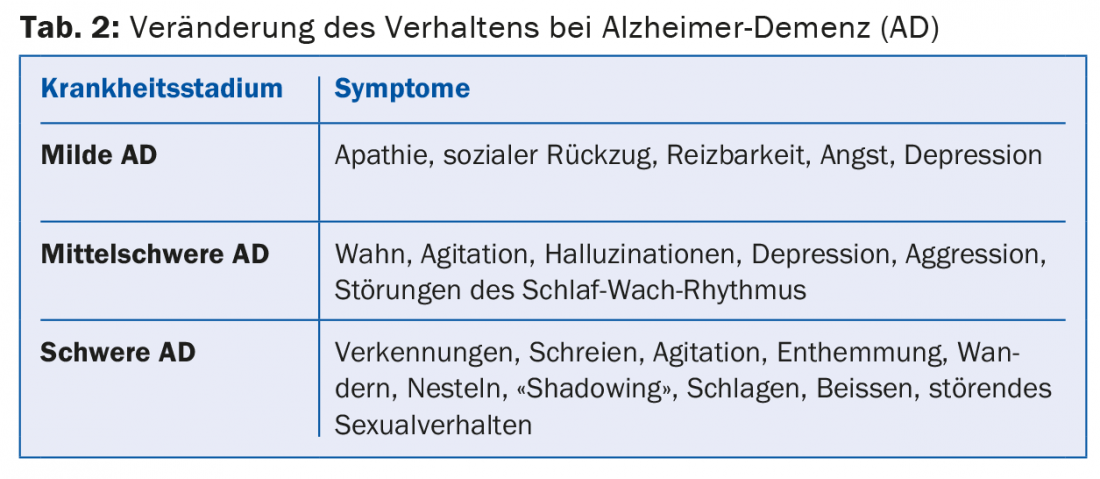

At the beginning of the disease, the condition of the affected person is often characterized by drive disorders, anxiety, depression and irritability. Some patients also experience schizophrenia-like symptoms such as hallucinations, delusional ideas, and agitation in the middle stages of the disease. In the late stage, stereotypic behavior such as wandering, screaming, disinhibition, etc. may occur in addition to disturbances of the sleep-wake rhythm. Some forms of dementia even manifest themselves through an earlier appearance of the behavioral disorders, e.g. Lewy body dementia with visual hallucinations or fronto-temporal dementia with marked personality changes (tab. 2).

While cognitive impairment and daily living skills show a continuous deterioration in the course of dementia, BPSD show an episodic character in the course of dementia development, often disappearing or turning into the opposite after a few weeks or months. Behavioral and cognitive disorders equally affect and worsen the daily living skills of the affected person. Thus, optimal treatment of BPSD can achieve a positive impact on both cognitive abilities and daily living skills.

The consequences of BPSD are serious for both the affected person and their relatives or caregivers: BPSD lead to faster cognitive decline, deterioration of daily living skills, massive losses in quality of life, earlier hospital or nursing home admission, and an increase in care costs. (Tab.3). Up to 50% of family caregivers develop clinically relevant depression over time.

Diagnosis of non-cognitive symptoms

The identification and diagnosis of BPSD are main tasks of the physician. They require close examination of behavior, involvement of caregivers, extraneous history, and also implementation of standardized and established testing procedures to detect BPSD. The most well-reviewed and widely used instrument to assess and quantify BPSD in practice is the Neuropsychiatric Inventory, NPI-D [5]. By recording behavioral disturbances using NPI-D, the frequency of individual symptoms, their severity, and the extent of caregiver distress can be identified. Nevertheless, the complex differentiation of BPSD from mental symptoms in other psychiatric disorders such as depression, schizophrenia, or delirium in the early stages of dementia can lead to significant differential diagnostic difficulties.

Therapeutic management

In the treatment of dementia, a constant and empathetic relationship between the physician and the affected person or his or her family caregivers or caregivers is of central importance. Not only from a therapeutic point of view, but also from a primarily preventive point of view, it is very important to find an appropriate approach to the personality of the sick person, to his habits and values. Only in this way can an individual treatment concept be developed that is tailored to the needs of the person concerned.

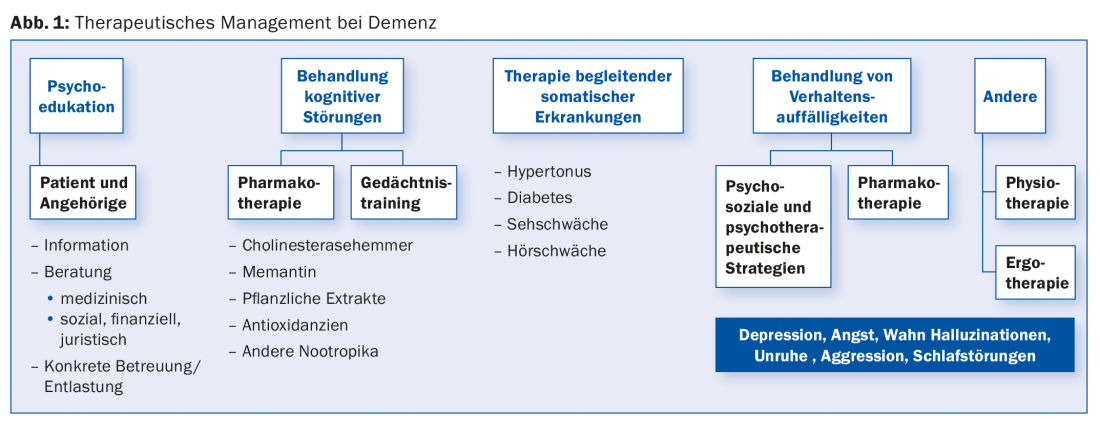

Before the treatment of BPSD, a careful analysis of the conditions of its development as well as a correct diagnosis of the respective symptomatology are indispensable. According to the recommendations of all international and national guidelines for the treatment of BPSD, it is clear that the preventive or non-drug measures should be preferred to drug treatment [6]. These measures, such as structuring the psychosocial environment and a range of behavioral therapy interventions, clearly reduce the incidence and severity of conduct disorder. The therapy includes milieu therapeutic interventions, but also various forms of memory training as well as movement, art and activation therapy. The relatives should be involved in the treatment as soon as possible. Psychoeducation of those affected in the earlier stages of the disease as well as of their relatives shows high effectiveness in reducing BPSD. Only if these measures do not achieve success should therapy be supplemented with drug treatment strategies (Fig. 1).

Drug treatment of BPSD

The basis of any treatment of AD is therapy with acetylcholinesterase inhibitors (donepezil, rivastigmine, galantamine). These medications cause a temporary delay in symptom progression and have a positive impact on BPSD. There is no approval of these agents in other forms of dementia today. Based on the available clinical studies and known neuropathological changes, their use in vascular, Lewy body and Parkinson’s dementia is quite appropriate. Memantine is indicated and approved for the treatment of moderate and severe AD (MMST <14) and primarily for the treatment of BPSD.

Various psychotropic drugs, especially atypical neuroleptics and newly developed antidepressants, are used to affect BPSD (e.g., depressive disorders, anxiety, delusional symptoms, agitation, and sleep disturbances). Poor tolerability, numerous concomitant medications in multimorbidity, poor compliance due to cognitive impairment, and altered metabolism complicate and complicate medication management of BPSD. It is therefore of utmost importance to know the desirable and undesirable or paradoxical effects of the most common psychotropic drugs. The newer selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (sertraline, citalopram, escitalopram) are first-choice agents for the treatment of depressive states in dementia due to their good tolerability and favorable side effect profile. Its anxiolytic effect speaks for its use, since depression in demented patients is often accompanied by anxiety symptoms.

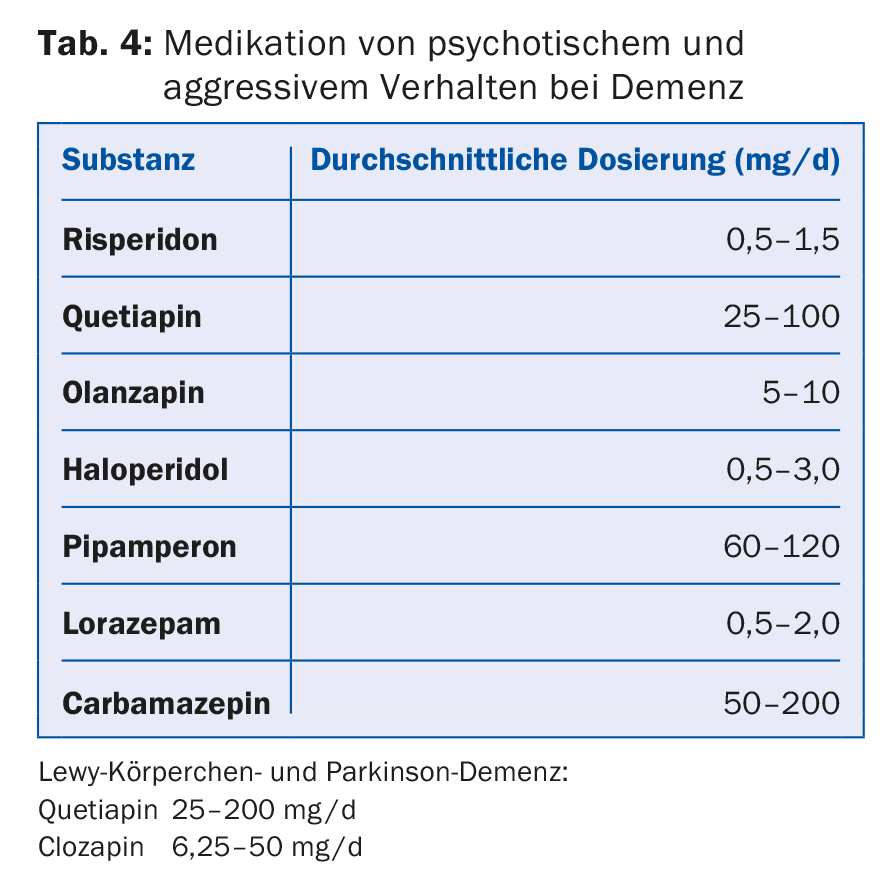

Newer neuroleptics with fewer extrapyramidal side effects (risperidone, quetiapine, and olanzapine) should be preferred for acute and prominent behavioral disturbances such as aggressiveness, delusions, and agitation (Tab.4). In an acute situation with pronounced behavioral disturbances, initial administration of a classic neuroleptic such as haloperidol may be appropriate, which is later replaced by a newer neuroleptic in an overlapping fashion. Only risperidone has approval for the treatment of BPSD. The use of other neuroleptics is off-label. Treatment with neuroleptics carries a higher risk of cerebrovascular and thromboembolic events and has been shown to increase mortality [7]. Therefore, this treatment should only be used after all non-drug measures have been exhausted, with the lowest possible dose, limited in time and under close monitoring.

The same restrictions due to serious side effects such as risk of falls, respiratory depression, and loss of effect apply to the use of benzodiazepines such as lorazepam, oxazepam, and temazepam, which are often used for anxiety and sleep disorders. The hypnotically active antidepressants and neuroleptics such as trazodone, trimipramine and doxepin have a positive effect on sleep duration and sleep quality.

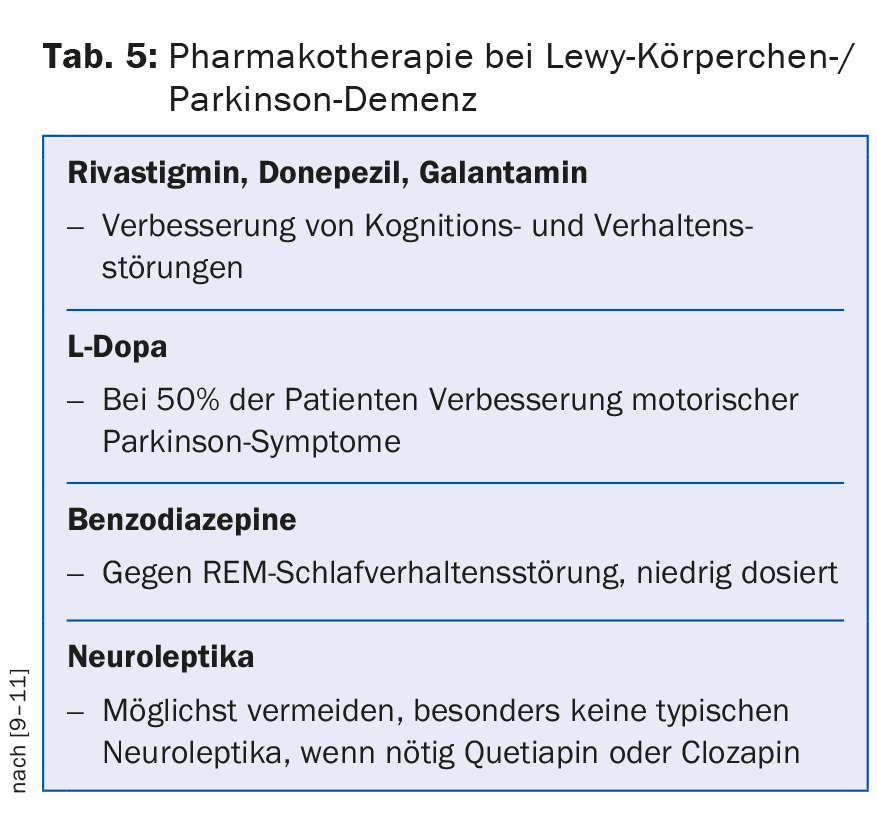

In principle, substances with anticholinergic side effects should be avoided. In Lewy body dementia and Parkinson’s disease, the agents with anticholinergic side effects should not be used. In these dementias, acetylcholinesterase inhibitors and low-dose use of quetiapine show beneficial effects on concomitant psychotic symptoms in the first lines. In the absence of response, clozapine is considered a second-line drug (Table 5) . In vascular forms of dementia, antipsychotics should be avoided because of the increased risk of cerebrovascular events. As a general rule, “start low, go slow” applies to drug treatment for the elderly. Generally, a lower target dose, usually one-third of the normal adult dose, is aimed for.

Conclusion

Dementia diseases are incurable until today, which is why all medical measures in the development of the disease have a palliative character. Nevertheless, therapeutic nihilism is not appropriate. Optimal treatment of BPSD leads to a significant improvement in the quality of life of the affected person and family caregivers and often prevents admission to a psychiatric institution, thus not only preventing and saving the traumatizing change of milieu for dementia patients, but also high costs for inpatient treatment.

Literature:

- Teri L, Larson EB, Reifler BV: Behavioral disturbance in dementia of the Alzheimer’s type . Journal of the American Geriatric Society 1988; 36: 1-6.

- Finkel SI: Managing the behavioral and psychological signs and symptoms of dementia. Int Clin Psychopharmacol 1997; 12(Suppl. 4): S25-28.

- Haupt M, Kurz A: Predictors of nursing home placement in patients with Alzheimer’s disease. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry 1993; 8: 741-746.

- Förstl H, et al: Neuropathological correlates of psychotic phenomena in confirmed Alzheimer’s disease. Archives of General Psychiatry 1994; 165: 53-59.

- Cummings JL: The Neuropsychiatric Inventory. Neurology 1994; 44: 2308-2314.

- Swiss Expert Group: Recommendations for Diagnosis and Therapy of Behavioral and Psychological Symptoms of Dementia (BPSD). Practice 2014; 3: 135-148.

- Gill SS, et al: Atypical antipsychotic drugs and risk of ischaemic stroke: population based retrospective cohort study. BMJ 2005; 330(7489): 445.

- Lyketsos CG, et al: Mental and behavioral disturbances in dementia:findings from Cache County Study on Memory and Aging. Am J Psychiatr 2000; 157: 708-714.

- Burns A, et al: Clinical practice with anti-dementia drugs: a consensus statement from British Association for Psychopharmacology. J Psychopharmacol 2006; 20: 732-755.

- Emre M, et al: Rivastigmine for Dementia Associated with Parkinson’s Disease. N Engl J Med 2004; 351: 2509-2518.

- McKeith I, et al: Efficacy of rivastigmine in dementia with Lewy bodies: a randomized, double blind, placebo-controlled international study. Lancet 2000; 356: 2031-2036.

GP PRACTICE 2015; 10(8): 34-38