The treatment of adolescents and young adults who develop cancer falls into a “skills gap” between pediatric oncology and adult oncology. Patients are at high risk for late complications. Therefore, consistent follow-up care must be provided over a long period of time.

In developed countries, cancer is the leading cause of disease-related death in adolescents and young adults (AYA). In Europe, cancer is the third leading cause of death after traffic accidents and suicide [1]. The age group of AYA is not uniformly defined; in Europe, it often includes 15- to 29-year-olds, but according to the currently valid definition of the US National Cancer Institute in consultation with the European Network for Cancer in Children and Adolescents (ENCCA), the term applies internationally to 15- to 39-year-olds [2]. AYA, unlike children and older patients with cancer, have very different medical and psychosocial needs. Therefore, this age group presents a special challenge to the physician providing care. The prognosis for young adults with cancer is better than average, with more than 80% being permanently cured. Therefore, special attention must be paid to late and long-term sequelae in the follow-up of this particular group of patients. In addition, follow-up care should be lifelong. Despite good cure rates, the improvement in survival achieved in recent years is not as good as in children or older people with cancer. Therefore, there is an increased focus on this age group with the goal of further improving survival, therapy and care.

Epidemiology and incidence

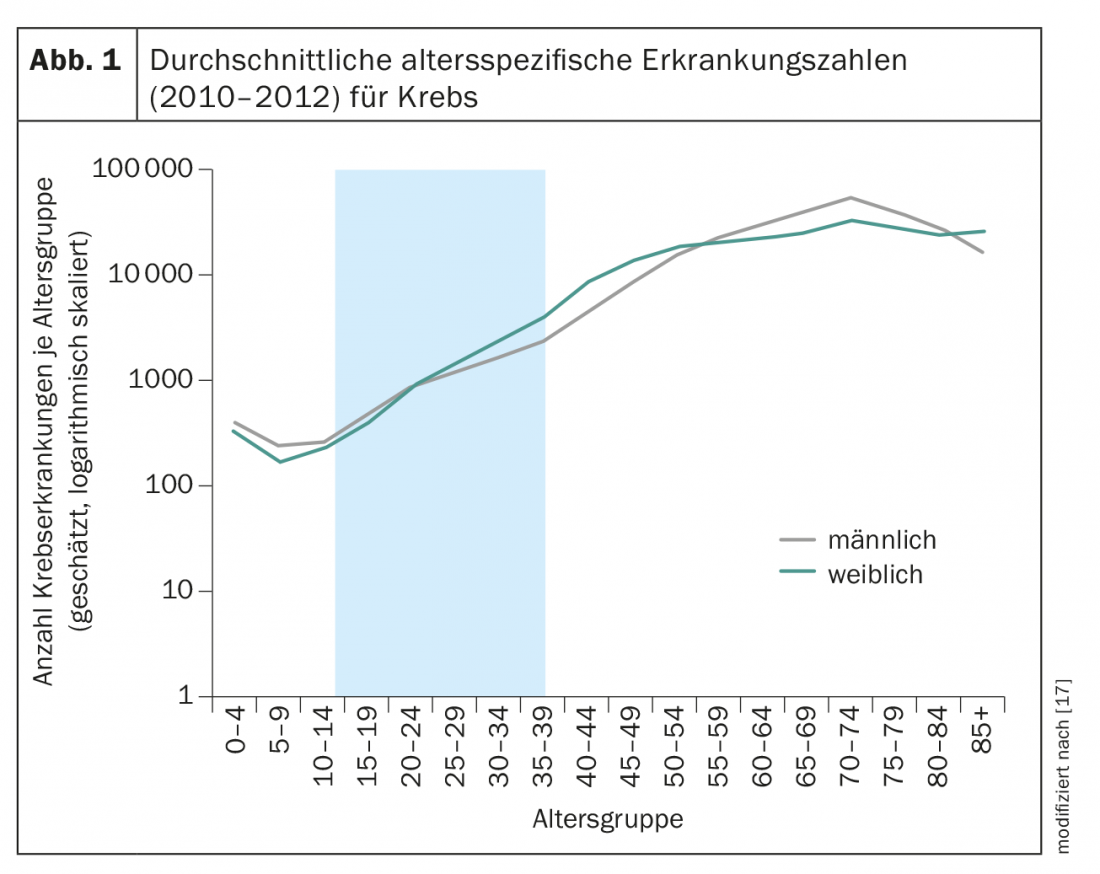

Cancer is a disease of older age; among 15- to 39-year-olds, cancer occurs relatively rarely (Fig. 1). Out of a total of 480,000 new cases of cancer in Germany per year, around 15,000 new cases are diagnosed among 15- to 39-year-olds. Between the ages of 15 and 24, the rate of new cases is the same for men and women; from the age of 25, more women than men develop cancer. From the age of 55, the situation is different again, with significantly more men developing cancer than women (Fig. 1). These figures can be easily transferred to Switzerland on a per capita basis (Germany approx. 80 million inhabitants, Switzerland approx. 8 million inhabitants).

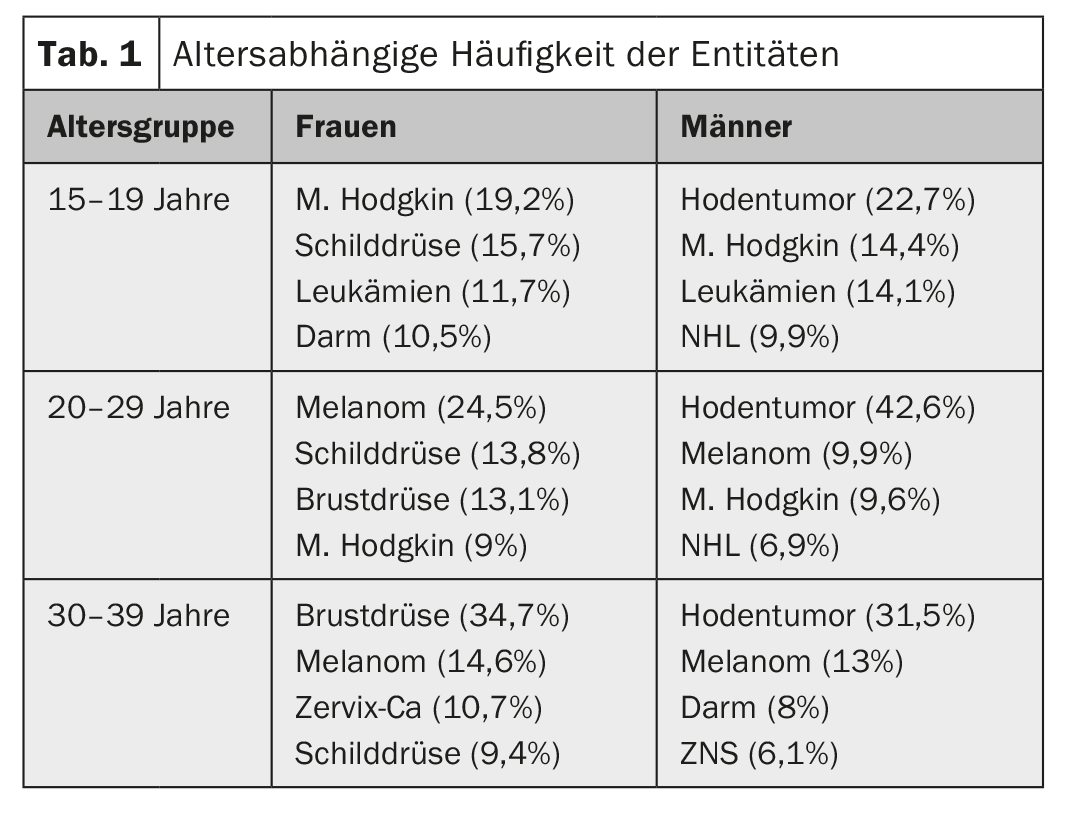

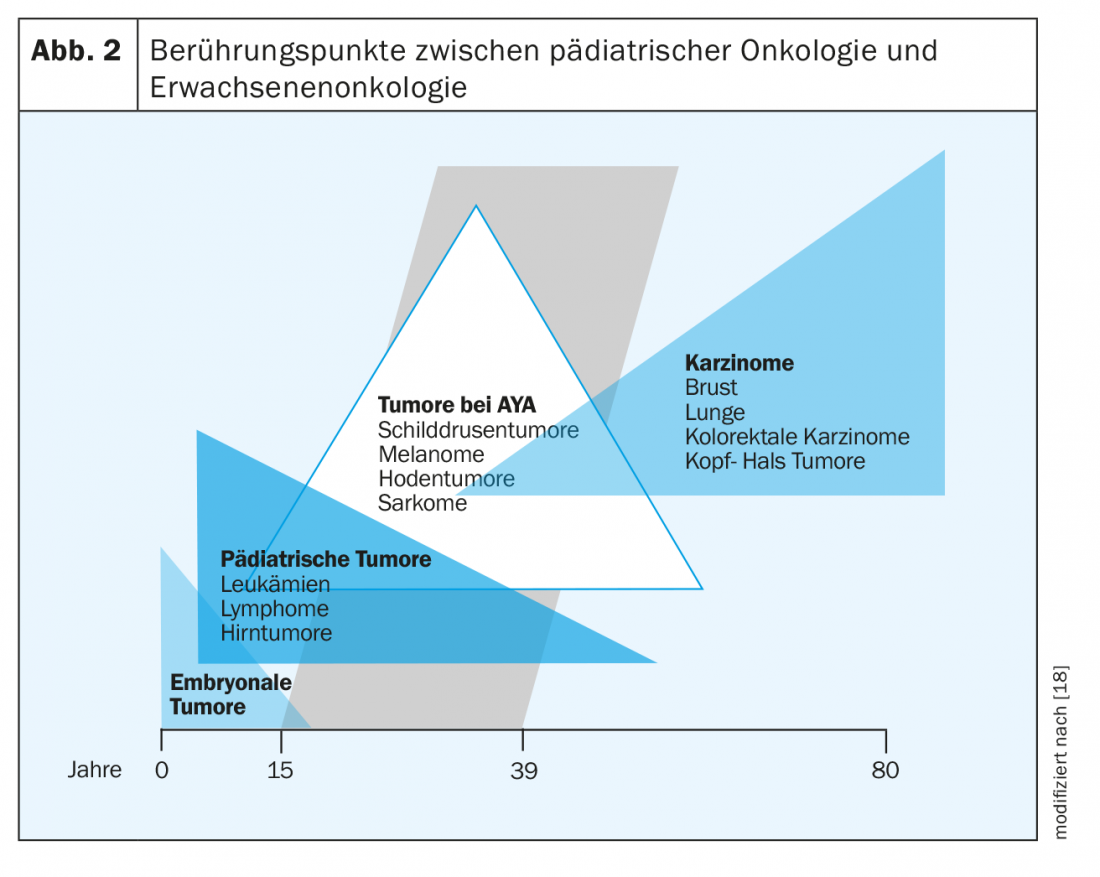

Among adults, the four most common cancers are prostate, breast, lung, and colorectal. Overall, they account for 50% of all new cancer cases. AYA show completely different cancers depending on age. While pediatric tumors such as leukemias and lymphomas are still frequently seen in the 15-19 age group, solid tumors such as thyroid carcinomas, melanomas, testicular tumors or breast cancer become more common with increasing age, and the solid tumors of adults are increasingly seen in the 25-39 age group. (Tab. 1 and Fig. 2).

Etiology

The etiology of cancer in AYA is not well studied and in some cases unclear. It is believed that cancer often develops spontaneously and independently of familial exposure and environmental influences. Genetic or familial syndromes (e.g., familial adenomatous polyposis coli, FAP) account for less than 5% of cancer cases in AYA. Environmental factors or risk factors are known for some cancers. These include UV light for melanoma, HPV infection for cervical cancer, HIV as a risk factor for lymphoma (particularly Burkitt’s lymphoma, Kaposi’s sarcoma, and NHL), and EBV infection, which is associated with the occurrence of Hodgkin’s lymphoma and endemic Burkitt’s lymphoma. For some tumors, a connection with the stage of life is also suspected; for example, osteosarcomas occur more frequently during puberty, when bone growth is particularly strong [3]. An additional risk factor for cancer in AYA is early childhood cancer that has been treated with chemotherapy or radiation therapy.

Special features at AYA

Heterogeneity: For all those affected, the diagnosis of cancer is one of the most drastic experiences in life. In the AYA age group, however, thoughts of illness and one’s own death are still far away. Already in themselves, AYA are a very heterogeneous group of patients with medically and psychosocially very different needs. 15- to 24-year-old patients are going through puberty, are breaking away from the parental home, are seeking acceptance from friends and partners, are in the process of sexual orientation, are having their first sexual experiences, are in education or have just entered the workforce. The risk behavior of this age group is high and they tend to engage in unhealthy behaviors (addiction problems, smoking, alcohol, poor eating habits, etc.). Compliance, acceptance, and adherence to therapy are often limited and thus worsen the prognosis [4]. The “older” part is in the process of consolidating one’s own personality. Young adults between the ages of 18 and 39 are busy pursuing careers, starting families, or becoming parents. In these phases of life, the focus is on mastering many new life tasks and goals. These challenges and processes are disrupted by the existentially threatening diagnosis of cancer. The processes stagnate, the main focus must be on ensuring survival. As a result, heteronomy and dependency are on the rise again. Compared with older patients, AYA are more likely to have psychosocial deficits during their course [5] and are more burdened by financial problems.

Therapy and care of AYA: In terms of therapy, a “skills gap” between pediatric oncology and adult oncology is evident in the care of patients with cancer in this age group. In principle, therapy is no different from that for older patients, but AYA are treated much less frequently in trials, especially compared with children (pediatric trials up to 18 years, adult trials 18 to 65 years). Internationally, additional controversy exists as to whether AYA with leukemias, lymphomas, Hodgkin lymphomas, sarcomas, and certain brain tumors, respectively, are better treated in pediatric or adult protocols. These differ in dosage, duration of therapy and intervals, as well as the use of stem cell transplants. Due to different pharmacokinetics or distribution and metabolism of chemotherapeutic agents in AYA compared to adults, as well as altered hormonal influences, it is debated whether therapy in pediatric protocols for AYA would be associated with better outcome. Only for ALL this could be shown, for other tumors there are no studies on this [6,7].

Tumor biology: tumors in AYA often show different tumor biology than the same tumors in children or adults, affecting prognosis as well as treatment response. Thus, melanomas in AYA patients are more likely to have BRAF mutations with better response to BRAF inhibitors. In contrast, breast carcinomas are more often triple-negative (estrogen receptor, progesterone receptor, and HER2-negative) in those under 40 years of age. This results in fewer treatment options as well as a poorer prognosis. Similarly, acute leukoses with unfavorable molecular or cytogenetic marker profiles (Ph+ ALL, less frequently TEL1-AML, ALL) and rhabdomyosarcomas with histologically and cytogenetically unfavorable subtypes (alveolar rhabdomyosarcomas) are more frequently seen compared with children [1]. These molecular or cytogenetic differences may be a starting point to improve the therapy and outcome of AYA in the future by more targeted therapies.

Survival, mortality: 30 years ago, the AYA age group had significantly better survival than pediatric patients with cancer, especially due to tumors with good prognosis. In the 1990s, overall survival improved dramatically, particularly for children with cancer, but the improvement in overall survival for AYA was much less pronounced [3]. The reasons for this could be lack of AYA guidelines, few available studies and therefore infrequent inclusion in clinical trials, different pharmacokinetics of chemotherapeutic agents, delayed diagnosis (e.g., in the United States, AYA are least likely to have health insurance; in addition, geographic factors play a role there), and lack of treatment adherence and compliance.

As a result of these poor treatment outcomes and lack of progress in overall survival, this age group has therefore come under increasing scrutiny in recent years. There has been an increased awareness of their special needs with improved care options, so AYAs have also seen a resurgence in overall survival in recent years [8,9]. However, the improvement in survival in AYA does not affect all tumor types and is still significantly worse for ALL and AML, Hodgkin lymphoma, NHL, astrocytomas, Ewing sarcomas, and rhabdomyosarcomas than in children [10].

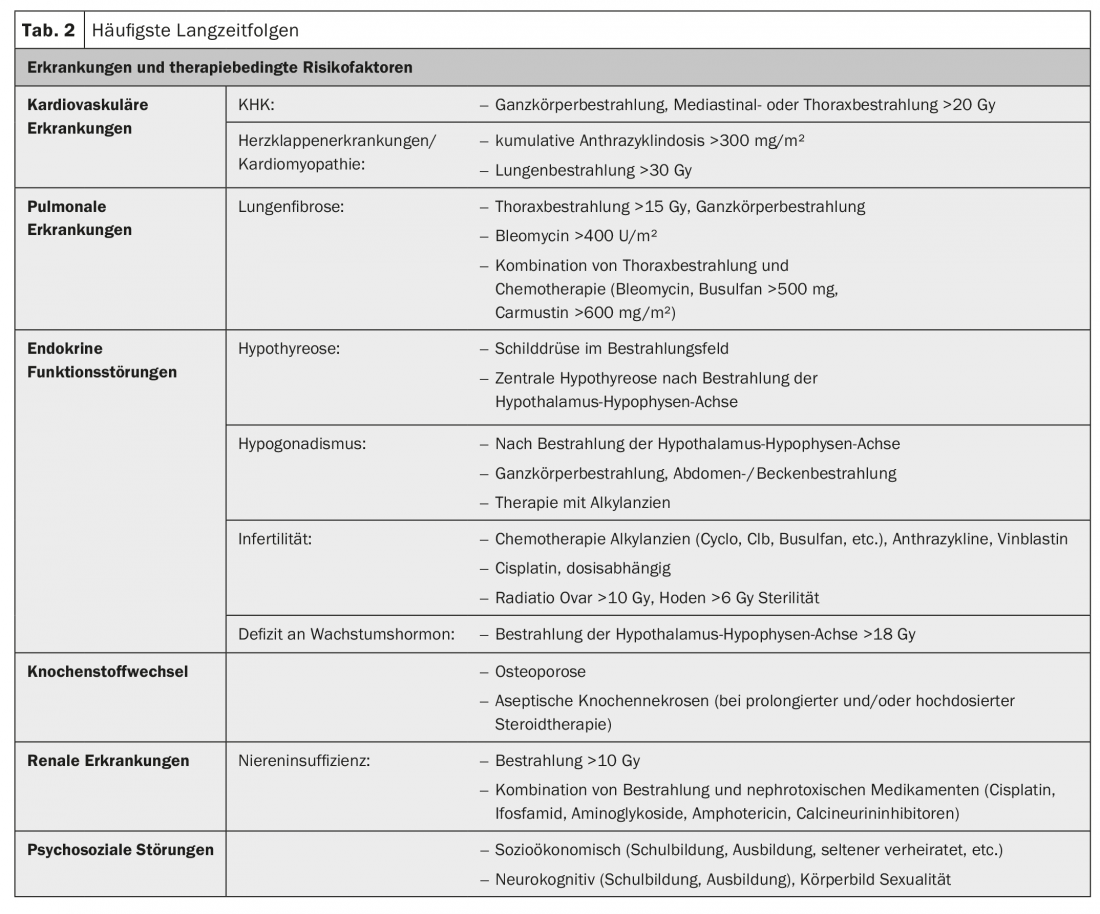

Therapy-related late sequelae: Overall survival in AYA is very good at >80%; however, more than 60-80% suffer from therapy-related long-term sequelae, which are often associated with significant impairment of quality of life. Compared to healthy siblings, AYA are eight times more likely to suffer from comorbidities 30 years after therapy [11]. Comorbidities not only occur five to ten years after the end of therapy, but may ultimately continue to occur after >30 years [12]. Risk factors for the occurrence of comorbidities that cannot be influenced are age of onset, tumor type, and type and intensity of treatment (chemotherapy, radiotherapy, or combination). Influenceable risk factors for the occurrence of comorbidities are lifestyle habits such as smoking, eating behavior as well as obesity and environmental factors such as sun exposure. Therefore, it is imperative to provide good education and primary prevention during the follow-up of AYA.

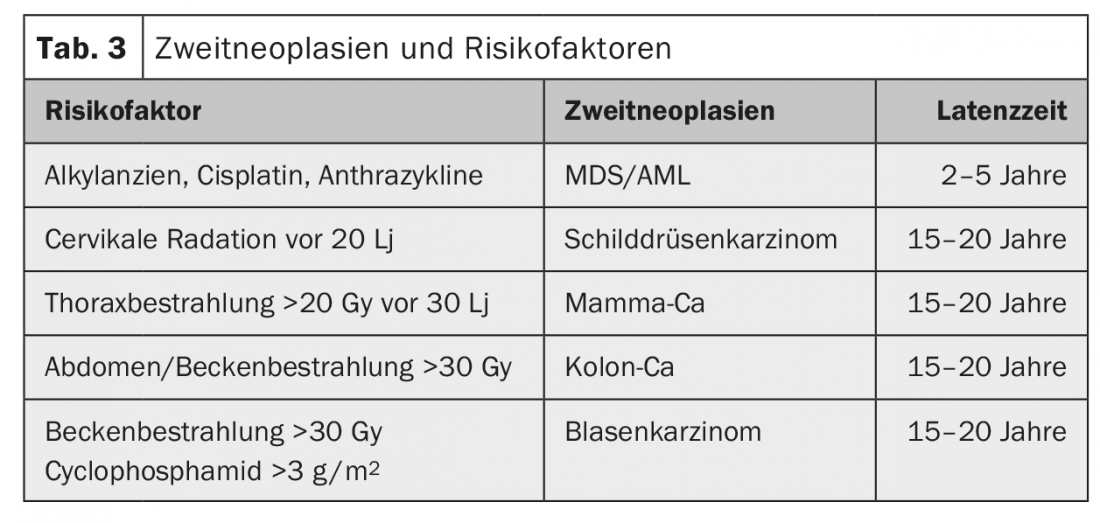

The most common late effects are cardiovascular, pulmonary, and endocrine disease, with cardiac disease being the leading cause of non-cancer mortality [13]. In addition, bone metabolism as well as the kidney may be affected, and AYA are also more likely to suffer from psychosocial disorders (Table 2) and have a significantly increased risk of second malignancies [14]. The risk is approximately doubled to tripled [15]The type of second malignancy depends on the initial disease and the therapy administered (or its mutagenic potential) (Tab. 3) . The highest risk for a contralateral tumor exists in patients with mammary or testicular tumors and after combined radio-chemotherapy or high-dose therapy. Second malignancies can occur within the first two years but also after more than 20 years, with hematologic neoplasms usually occurring earlier than solid tumors (Table 3).

Therefore, it is important to provide good patient education prior to therapy with discussion of all relevant side effects to be expected. It is essential to pay special attention to fertility in this age group and the possibilities of fertility preservation with counseling in a facility qualified for this purpose.

Follow-up: Follow-up for AYA with survived cancer therapy must be lifelong. In these patients, depending on the therapy administered, there is a lifelong increased risk in particular for cardiac, pulmonary and endocrine late effects as well as an increased risk of developing a second malignancy. Therefore, it is important to have a good follow-up plan as well as patient education so that attention is paid not only to good secondary prevention but also to good primary prevention. In addition, an attempt must be made not to stigmatize and unsettle the actually healthy patient by regular follow-up visits. Despite regular appointments with the doctor, he should be enabled to lead as normal a life as possible. It would be desirable, as is already established in the Netherlands and the United Kingdom, to create a separate care structure for this group of patients with outpatient and inpatient care in an interdisciplinary or multidisciplinary approach [16].

Take-Home Messages

- There is still a need for improvement in diagnosis, therapy and care.

- Therapy and care should take place in specialized centers, if possible. The transition to adult oncology must be well managed and regulated.

- Adolescents and young adults who develop cancer are at high risk for late effects (cumulative >70%). Therefore, consistent follow-up care must be provided long after the actual tumor follow-up.

- Aftercare means prevention: Special attention must be paid to long-term consequences. In this context, patient education in the sense of primary, secondary and tertiary prevention is also coming into focus.

Literature:

- Hughes N, Stark D: The management of adolescents and young adults with cancer. Cancer Treat Rev 2018; 67: 45-53.

- Coccia PF, et al: Adolescent and young adult oncology. Clinical practice guidelines in oncology. J Natl Compr Canc Netw 2012; 10(9): 1112-1150.

- Bleyer A, Viny A, Barr R: Cancer in 15- to 29-year-olds by primary site. Oncologist 2006; 11(6): 590-601.

- Butow P, et al: Review of adherence-related issues in adolescents and young adults with cancer. J Clin Oncol 2010; 28(64): 4800-4809.

- Merckaert I, et al: Cancer patients’ desire for psychological support: prevalence and implications for screening patients’ psychological needs. Psychooncology 2010; 19(2): 141-149.

- Veal GJ, Hartford CM, Stewart CF: Clinical pharmacology in the adolescent oncology patient. J Clin Oncol 2010; 28(32): 4790-4799.

- Boissel N: How should we treat the AYA patient with newly diagnosed ALL? Best Pract Res Clin Haematol 2017; 30(3): 175-183.

- Bleyer A, et al: Children, adolescents, and young adults with leukemia: the empty half of the glass is growing. J Clin Oncol 2012; 30(32): 4037-4038; author reply: 4038-4039.

- Barr RD, et al: Cancer in Adolescents and Young Adults: A Narrative Review of the Current Status and a View of the Future. JAMA Pediatr 2016; 170(5): 495-501.

- Trama A, et al: Survival of European adolescents and young adults diagnosed with cancer in 2000-2007: population-based data from EUROCARE-5. Lancet Oncol 2016; 17(7): 896-906.

- Oeffinger KC, et al: Chronic health conditions in adult survivors of childhood cancer. N Engl J Med 2006; 355(15): 1572-1582.

- van der Pal HJ, et al: High risk of symptomatic cardiac events in childhood cancer survivors. J Clin Oncol 2012; 30(13): 1429-1437.

- Dietz AC, Sivanandam S, Konety S, et al: Evaluation of traditional and novel measures of cardiac function to detect anthracycline-induced cardiotoxicity in survivors of childhood cancer. J Cancer Surviv 2014; 8(2): 183-189.

- Woodward E, et al: Late effects in survivors of teenage and young adult cancer: does age matter? Ann Oncol 2011; 22(12): 2561-2568.

- Turcotte LM, et al: Risk of Subsequent Neoplasms During the Fifth and Sixth Decades of Life in the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study Cohort. J Clin Oncol 2015; 33(31): 3568-3575.

- Husson O, Manten-Horst E, van der Graaf WT: Collaboration and Networking. Prog Tumor Res 2016; 43: 50-63.

- Hilgendorf, et al: Onkopedia Guidelines, Adolescents and Young Adults (AYA), 2016. https://www.onkopedia.com/de/onkopedia/guidelines/heranwachsende-und-junge-erwachsene-aya-adolescents-and-young-adults/@@view/html/index.html, as of Dec. 18, 2018.

- Bleyer A: Latest Estimates of Survival Rates of the 24 Most Common Cancers in Adolescent and Young Adult Americans. J Adolesc Young Adult Oncol 2011; 1(1): 37-42.

InFo ONCOLOGY & HEMATOLOGY 2019; 7(1): 10-13.