Before reaching into the painkiller drawer, differential diagnostic considerations and causal therapy must be considered: First and foremost, the targeted clinical examination and ultrasound are helpful. The goal of adequate pain management in the treatment of musculoskeletal complaints is to improve physical and social activity. Multimodal pain therapies have proven effective in the treatment of chronic pain conditions. Patients should be encouraged to engage in their activities of daily living as much as possible within pain limits. Symptomatic osteoporosis is a common cause of musculoskeletal complaints in elderly patients.

Chronic or acute musculoskeletal pain is a common reason for consultation in family practice. The common consequence of the different pain syndromes are functional deficits with resulting impairment of everyday activities and quality of life. The goals of adequate pain management are to improve physical and social activity with a consecutive reduction in pain.

Pain in the musculoskeletal system may often be difficult to assess, but precise clinical examination as well as additional examinations, especially sonography, supported by differential diagnostic considerations, often lead to targeted therapeutic measures with predictable success.

Chronic musculoskeletal pain

Chronic pain is one of the most pressing health concerns in this country. The socioeconomic impact is immense. Most chronic pain patients suffer from musculoskeletal complaints, of which back pain is the most commonly reported.

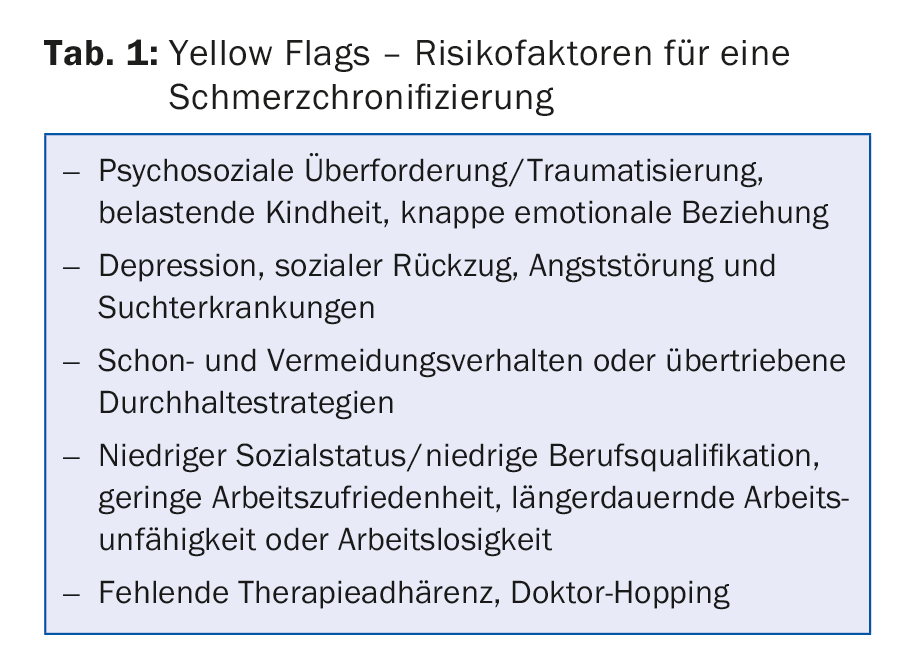

In contrast to the acute pain syndrome, chronic pain increasingly detaches the perception of pain from the physical problem (tab. 1). Pain as an unpleasant emotional experience is subjective. Non-somatic reasons have a decisive influence on the course of the disease. For the patient, identifying the somatic core – often the trigger of the pain disorder – is a prerequisite for initiating successful pain management. On the part of the physician, special attention must be paid to the additional factors that promote and intensify pain.

Patients with chronic pain find themselves in a vicious circle: pain leads to fear of movement and thus to avoidance of physical performance, as well as to relieving postures that intensify the pain. Moreover, patients themselves often find themselves in a general downward spiral in terms of social and work environment. Prolonged pain affects the psyche, which in turn increases the perception of pain. In addition to acute pain intensification, these unfavorable interactions also lead to chronic persistence of pain symptoms.

Chronic pain patients have usually gone through an odyssey of diagnostic and therapeutic measures. The patients are met with rejection by society and not infrequently by medical professionals. A non-judgmental acceptance of the problem, empathy and patience are therefore important prerequisites in the treatment of chronic pain patients. Talking with the patient provides important information about his or her ideas about the cause of his or her pain and his or her expectations regarding medical treatment. Patient education about pain development and pain processing can be helpful. This should be followed by a discussion of treatment goals.

How to treat?

Interdisciplinary multimodal pain therapies have proven effective in treatment. Here, an attempt is made to act on the somatic core of the pain disorder as well as on the psychosocial events. In addition to chronic pain patients, those at risk of chronicity in particular should be introduced to a multimodal therapeutic approach at an early stage. In most centers, an inpatient multimodal pain management program is co-managed by the medical staff along with specialists in physical therapy, occupational therapy, and psychotherapy or psychiatry, and often with additional stakeholders (specialized nursing, social services, parallel medical therapists). Therapeutic approaches can also be found in pastoral care or in the field of music.

Physiotherapy treatment includes mainly active physiotherapy approaches with home exercise instruction, specialized exercise therapy such as functional spinal gymnastics or equipment-based training (medical training therapy). Water therapy (walking bath) in a group is often supportive. In addition, passive measures such as TENS (transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation), massage, heat and cold therapy as well as electrotherapy and ultrasound can be used in individual cases.

Occupational therapy treatment works through motor-functional training of the movement sequences relevant to everyday life. Patients are trained by professionals in ergonomics at work and receive tips regarding daily structure and pacing (dynamic strategy in the management of activities). In addition, occupational therapists adapt aids and practice their use.

Psychotherapeutic procedures in pain therapy usually make use of the tools of cognitive behavioral therapy and attempt to detect unfavorable thoughts and behavioral patterns and gradually change them into positive thought processes. Important topics here are coping strategies for dealing with pain and relaxation exercises. In addition, there are starting points in the treatment of the depressive disorder that is often present at the same time.

Medicinal pain therapy is basically based on the WHO guidelines. The benefit of analgesic therapy should be evaluated at regular intervals. Standardized assessments help to objectify pain management. Even the regular recording of a simple VAS scale helps to monitor the therapy. In the outpatient setting, even well-controlled pain patients should have a medical consultation at least every three to six months. In addition, low-dose antidepressants should be used regularly in the pain management of chronic musculoskeletal pain. Tricyclic antidepressants and serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs) are effective in pain management. The evidence for the efficacy of serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) is somewhat weaker.

It should be noted that toxicity concerns are increasingly being raised for prolonged treatment with acetaminophen at doses greater than 3 g/d. In contrast, the side effect profile of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) in terms of gastrointestinal, renal and cardiovascular toxicity is well known. Clinical experience and a recent meta-analysis in osteoarthritis show that NSAIDs are superior to paracetamol in terms of efficacy. Because of the known side effects of NSAIDs, long-acting opiates and opioids are also increasingly used.

A multimodal therapeutic approach in the treatment of chronic pain patients is undisputed today. Complete freedom from pain is rarely achieved. However, the common goal of therapeutic efforts is to achieve the most acceptable pain intensity that allows for maximum physical and social activity.

Treatment of acute musculoskeletal pain

In acute musculoskeletal conditions, informing the patient of the often favorable spontaneous course is essential. An informative medical discussion about these facts and a time-limited symptom-oriented therapy are often sufficient in the treatment. All patients with musculoskeletal conditions should be encouraged to perform their activities of daily living as much as possible within pain limits. Secondary problems associated with immobility are thereby reduced, which in turn results in more rapid improvement of symptoms and a reduced risk of chronification.

In most patients with nonspecific acute musculoskeletal complaints, imaging can be omitted in the initial evaluation. On the other hand, a medical check-up in one to two weeks to assess the progress is almost always advisable.

Treatment of musculoskeletal complaints in elderly patients.

Especially in the elderly, untreated musculoskeletal complaints have negative effects with regard to mobility. Avoidance of physical activity leads to rapid onset of functional impairment. The consequences are social withdrawal and depressiveness. Treating the vicious circle of pain, depression, and sleep disturbance often requires a multimodal therapeutic approach. This is increasingly offered in the context of geriatric early rehabilitative complex treatments.

With regard to drug therapy for pain, it is important to take into account the declining liver and kidney function with age. In addition, increased drug-drug interactions need to be considered. Accordingly, the dose of NSAIDs should be adjusted downward in patients over 70 years of age. In addition to the basic analgesics paracetamol and metamizole, low-dose opiates are highly valued in pain management in elderly patients.

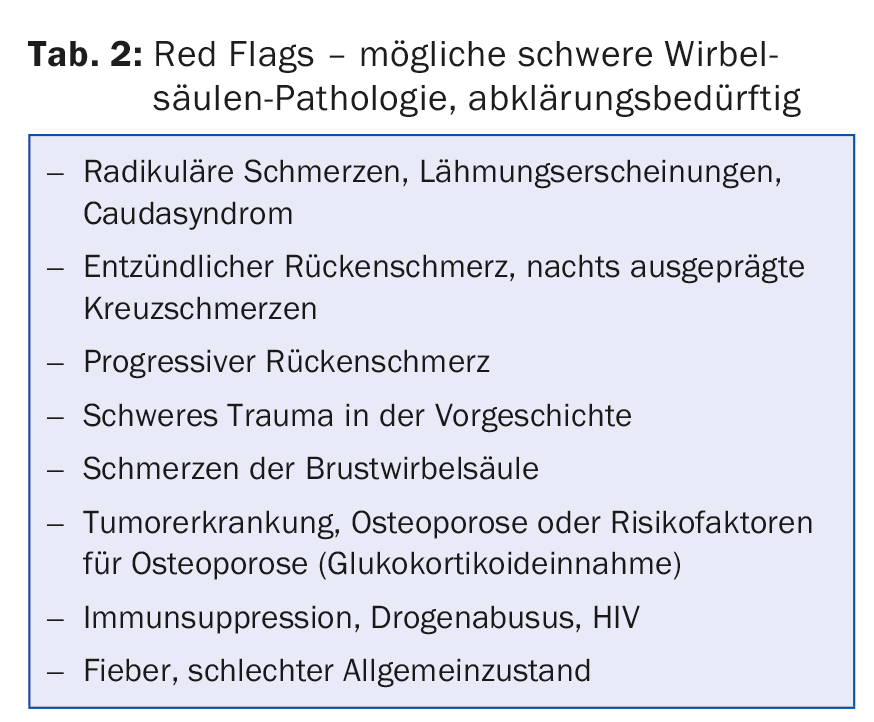

The prevalence of osteoporotic fractures in the spine and pelvic ring is difficult to estimate. From our perspective, however, they are very often the cause of musculoskeletal pain (tab. 2). It is certain that in the presence of an osteoporotic fracture, not only the risk of further fractures is increased, but also the general mortality. Accordingly, these patients benefit from osteoporotic treatment in addition to adequate pain management. Adequate postural/support aid (lumbar corset, trochanteric belt, etc.) improves mobility and reduces the need for analgesics.

Further reading:

- WHO: Towards a Common Language for Functioning, Disability and Health, ICF. World Health Organization: Geneva 2002.

- Breivik H, et al: Survey of chronic pain in Europe: prevalence, impact on daily life, and treatment. Eur J Pain 2006; 10(4): 287-333.

- Wulff I, et al: Interdisciplinary guidance for pain management in nursing home residents. Z Gerontol Geriatr 2012; 45: 505-544.

- Flor H, Fydrich T, Turk DC: Efficacy of multidisciplinary pain treatment centers: a meta-analytic review. Pain 1992; 49: 221-230.

- Bruyère, O, et al.: An algorithm recommendation for the management of knee osteoarthritis in Europe and internationally: A report from a task force of the European Society for Clinical and Economic Aspects of Osteoporosis and

- Osteoarthritis (ESCEO). Seminars Arthritis Rheum 2014; 44(3): 253-263.

- Guzman J, et al: Multidisciplinary bio-psycho-social rehabilitation for chronic low back pain. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2002; (1): CD000963.

- Bachmann S, et al: Rehabilitation and follow-up costs in patients with chronic low back pain. Phys Med Rehab Kuror 2008; 18: 181-188.

- Da Costa BR, et al: Effectiveness of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs for the treatment of pain in knee and hip osteoarthritis: a network meta-analysis. Lancet 2016 Mar 17. pii:S0140-6736(16)30002-2 [Epub ahead of print].

- Trelle S, et al: Cardiovascular safety of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs: network meta-analysis. BMJ 2010; 341: c3515.

HAUSARZT PRAXIS 2016; 11(6): 18-20