What is the importance of activity, exercise and sport in the treatment of chronic back pain? There is some talk of disuse and overuse due to activity and exercise in pain patients. This article discusses the value of active therapy/sport therapy based on a biopsychosocial understanding of the causes and rehabilitation of chronic back pain.What is the importance of activity, exercise, and sport in chronic back pain therapy? There is some talk of disuse and overuse due to activity and exercise in pain patients. This article discusses the value of active therapy/sports therapy based on a biopsychosocial understanding of the causes and rehabilitation of chronic back pain.

Through multimodal pain therapy, the patient should learn how to regulate his pain experience on his own. Physical deconditioning, but also the psychosocial and cognitive impairments are the result of fearful avoidance behavior (“fear-avoidance belief”). On the other hand, lack of exercise and deconditioning, as well as psychosocial stress, promote and reinforce anxiety avoidance behavior in chronic back pain patients.

The fear avoidance concept and variants

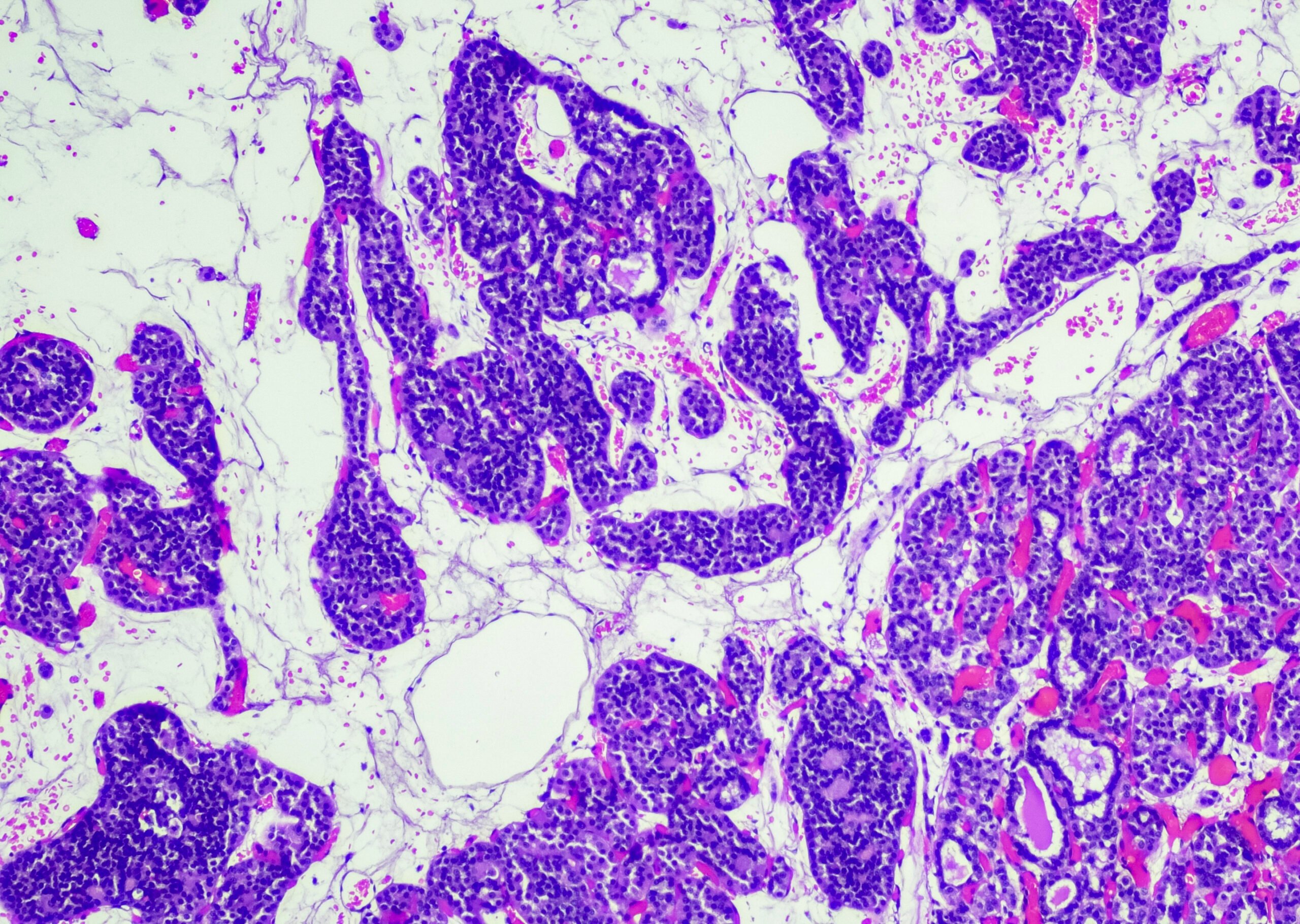

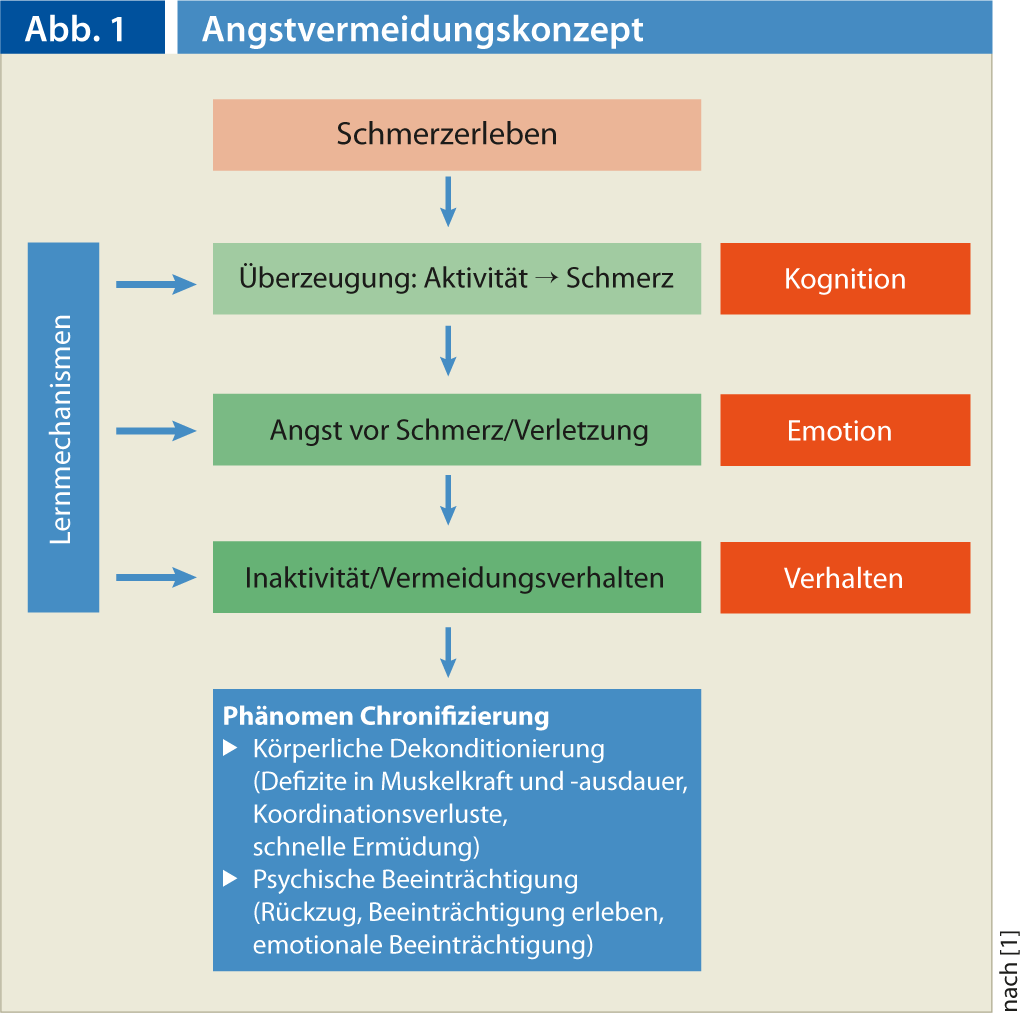

The fear-avoidance concept helps to understand the chronification of pain and can also be used for therapeutic principles (Fig. 1) [1].

Anxiety about activity can arise when pain experience leads to increasing avoidance behavior via cognitive and emotional factors. The end is at worst the immobilization of the affected person. Through emotional, cognitive and social preconditions and experiences, the fear of pain (expansion) becomes greater and greater, which eventually leads to more or less pronounced inactivity and avoidance behavior. This leads to physical deconditioning, which in turn increases psychological impairments.

The fear of worsening pain interferes with physical activity more than the physical disability itself does. The patient no longer experiences that there is a necessary connection between movement and pain [2]. Thus, also Leuw et al. 2007 that fear-avoidance behaviors in people with back pain are strongly related to limitations in physical performance (strength, coordination, endurance). Also, because this avoidance behavior has proven to be highly resistant to treatment – provided the “red flags” have been clarified and ruled out – identifying and treating the psychosocial factors of chronicizing back pain has become increasingly important.

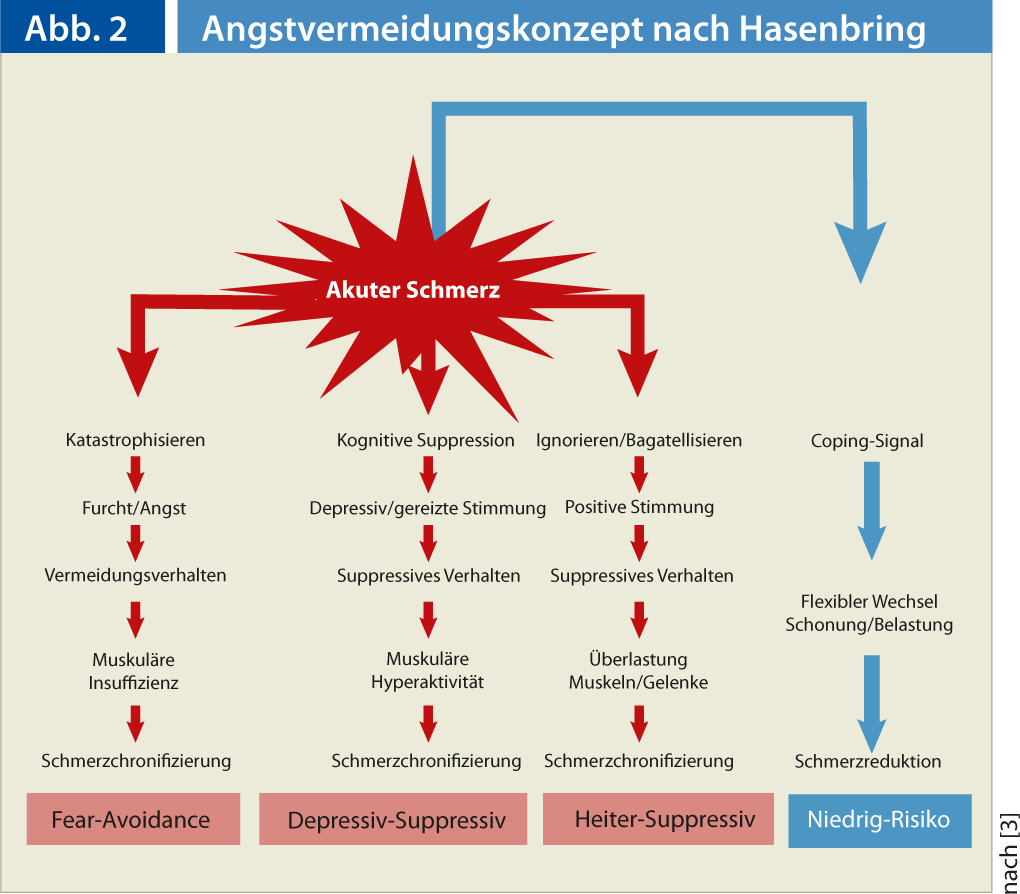

An extension of the fear-avoidance concept to explain chronic pain is shown by Hasenbring (Fig. 2) [3]. It distinguishes different character types in dealing with chronic pain:

- the fear-avoiding pain processing

- the depressive supressive pain processing

- the latent serene supressive pain processing.

These different pain processing characters require an appropriately individualized activation and cognitive-behavioral therapy program.

Pacing throughout the day despite disturbed mbody perception

The frequently observed overactivity-underactivity cycle leads to long-term pain increase and chronicity. Recording the activity-inactivity pattern of each individual pain patient is a prerequisite for planning an effective training concept and a balanced daily structure (“pacing”). The goal of pacing is to create a reasonably consistent level of activity throughout the day. Likewise, the training stimuli are gradually increased in small steps.

In the daily routine of the clinic, it is problematic for the supervising movement and sports therapists that many pain patients have a disturbed relationship with their body: Either the patients feel abandoned by their body, perceive it as “totally broken” or (the fewer ones) they go into therapy and training “hard as nails” without sensitivity. A disturbance of body perception [4] and an inability to perceive stress are evident, which is not only due to fear-avoidance behavior, but often seems to be a consequence of too little exercise experience and lack of exercise in adolescence and adulthood.

The patient may be superficially present and motivated in therapy, but without real participation. Especially in movement therapy, the pain patient is often not really physically and mentally present at all. He still lets everything happen more or less passively with him. The body is handed over for therapy and training. The resistance is not openly shown, but manifests itself in physical symptoms such as sore muscles or increased pain sensation [4].

Physical self-awareness and self-efficacy to reduce the pain response must therefore be intensively trained and exercised in addition to goal-oriented muscle function and endurance training.

What is sport?

“Sport” derives from the Old Latin disportare (to distract, disperse), which corresponds to the mental rather than the physical aspect. Here a reference to human neuroplasticity and the importance of relearning and reprogramming especially in people with chronic pain memory is allowed. “Patients must experience painlessly what they can do themselves, what they experience themselves. It is not what is prescribed and demonstrated to them, the feeling of self-efficacy is the learning impulse” [5, 6].

The following adaptations on the human body can be basically attributed to the exercise training and sports:

- Morphological adaptations (especially strength, endurance, mobility)

- Neurophysiological adaptations (coordination)

- Psychological effects.

How to train?

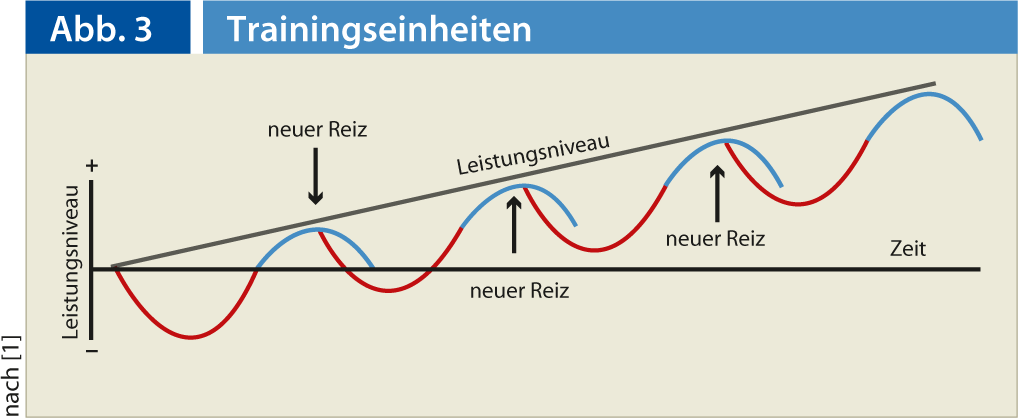

Optimal training adaptation must always be accompanied by effective load stimulation, which in turn depends on the current physical performance of the exerciser (Fig. 3) [1]. With a coordinated relationship of stimulus settings but also appropriate recovery, physical performance can be improved in this way. In the course of the training process, it is important to increase the load slowly and carefully. The expansion of the temporal scope of the requirements should precede the increase in intensity. To achieve and maintain the desired physical performance, it is necessary to repeat meaningful loads regularly and for a long time. Morphological and physiological changes in muscle and metabolism are detectable only after four to five months of training [7]. Health-oriented training should be as lifelong as possible and be diversified by varying the forms of exertion. In practical training implementation, age-dependent, biological and psychological performance must be taken into account.

Neurophysiological effects

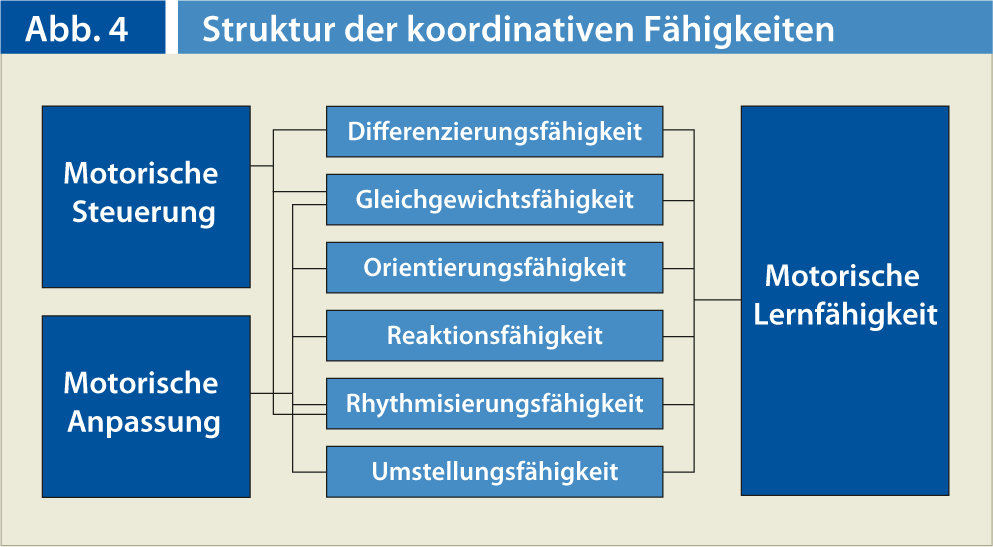

Life is always connected with movement. The ability to learn new movements and adapt them to new situations is based on the plasticity of the nervous system and the biochemical properties of the nerve cells. Controlling, adapting, and ultimately learning movements is achieved through coordination training [1] and is a learning process.

Adaptations and training in the coordinative, i.e. sensorimotor, area (Fig. 4) are always associated with conscious body perception and experience. Coordinative action skills go beyond sports. Meaningful human action is always an orienting and differentiating allocation, also in the sense of integrating and forming an equilibrium [8]. Learning progresses through differentiation processes. Differentiation means learning to distinguish sensory information through value-free, neutral body perception. Being able to differentiate gives more movement learning experiences, more experiences also mean more reference values, which in turn enriches the body’s own resources in partially ingrained automated movement patterns.

Orientation ability is also an active perceptual process as well as a product of spatial and temporal movement regulation. Those who want to successfully improve their coordinative action competence are guided by the methodological guiding principle of varying and combining different movement subskills: “Correct as little as necessary, vary as often as possible” [1, 8].

Psychological effects

The current state of knowledge on the relationship between physical activity and mental health is given by Schulz et al [9]. Physical training can have a similar effect on depression as drug therapy. It causes adaptations in the neurobiological mechanisms underlying mood improvement, but also has a positive effect on the psychological self-concept and self-efficacy model. Desensitization processes may play a role in the well-documented positive effect of physical activity on anxiety and anxiety disorders. The phenomenon of overtraining, which is known mainly among competitive athletes, shows that physical training does not always improve psychological well-being. Physical activity can prevent cognitive decline in old age and delay the development of dementia.

Finally, physical activity also exerts a positive influence on the hormonal stress regulation systems: In exercised individuals, these show a stronger reactivity and a faster ability to regenerate [9].

What does sports therapy do for chronic (back) pain patients?

Sports and exercise therapy is exercise training with behavior-oriented components that are planned and dosed by the therapist, coordinated with physicians and therapists from various disciplines, and carried out with the patient in a group. With appropriate means of sport, exercise and behavioral orientation, physical, psychological and psychosocial (affecting everyday life, leisure and work) impairments can be improved or damage and risk factors can be prevented. Sport and exercise therapy is based on medical, training and exercise science and padegogical-psychological as well as sociotherapeutic elements (Deutsche Vereinigung für Gesundheit, Sport und Sporttherapie, 2010).

Sports therapy defines itself at different levels of learning objectives:

- At the coordinative, sensorimotor learning target level

- At the motor learning target level

- At the affective and educational target level

- At the cognitive learning target level

The effect of sports therapy on coordinative, sensorimotor learning target level.

Here, the focus is on experiencing, perceiving and learning movement possibilities of one’s own body. Body awareness is a process-oriented approach to developing movement skills and is experience-oriented. Moving is experiencing one’s own body in a concentration on oneself. The self-evident, which is otherwise often ignored, is consciously experienced. For example, mindfulness practice [10, 11] also offers a good, simple concept for perceiving the body as it is. In mindfulness training, pain patients learn to observe the feelings that occur during pain like a neutral observer. At the same time, they learn to recognize the changeability and mutability of pain perception. The mindfulness training is introduced by a so-called body scan, a neutral perception of the body contact surfaces in the supine position. In addition to meditation and mindfulness integration into everyday life, gentle physical exercises from yoga, tai chi or qigong are consciously experienced and trained. [11].

The effect of sports therapy on the motor learning target level.

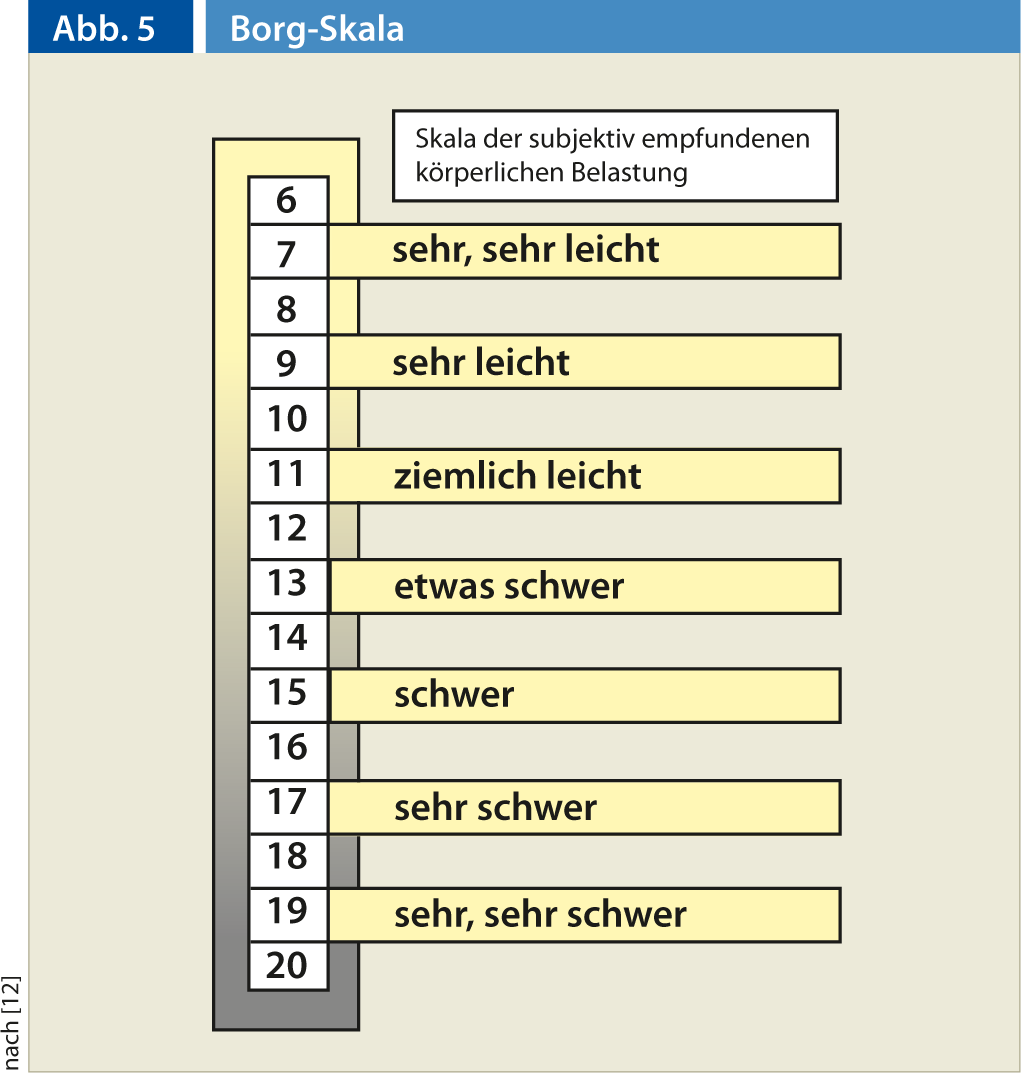

The primary goal is to train the various conditioning factors, such as strength, endurance, flexibility, and coordination, as part of medical training therapy for existing deconditioning. In addition to specific muscle function training, the focus is on training and, above all, on perceiving and getting to know the individual’s ability to cope with stress. The Borg scale, which reflects the subjective feeling of exertion during stress, provides a good aid here (Fig. 5) [12].

It should be noted here that, for example, an optimal load in a 20- to 30-minute general endurance workout can and should range from fairly light to somewhat heavy. In a strength endurance training of specific local muscle groups, on the other hand, the load should normally be felt at least or better as heavy after 20-30 maximum repetitions. The prerequisite is, of course, that pain is not the limiting factor during the execution of the movement (or increases during the load, which of course should lead to an interruption of the exercise).

The effect of sports therapy at the affective and educational goal level.

This is about creating long-term motivation to implement self-exercise programs and achieve a physically active lifestyle. Within the framework of health promotion through meaningful movement, the achievement of a playful attitude forms an overriding goal. The open outcome of an activity or movement with the risk of failure, the free combination of already known and skilled elements, the immersion in the moment in an activity (flower life) characterize the playful action. Play is as important as performance orientation and goal-oriented unilateral movement training. Flower life [13, 14] and mindfulness are as yet unnamed but central effective factors in health promotion through exercise and sport. Flow – the feeling of complete absorption of body and mind in an activity – requires mindfulness – awareness of one’s present experience. The person/patient comes back into contact with his corporeality and the present. This is an important foundation for making responsible, self-controlled decisions regarding one’s health behaviors [14].

The effect of sports therapy on the mcognitive learning target level.

This learning objective level is about imparting and training knowledge as the basis of independent and long-term health-related action and social competence. In sports therapy, the teaching of cognition should always be linked to direct practical movement experiences [15]. In addition to information and activation through “modern” teaching, such as the “new back school”, work hardening, work-specific training, should also be mentioned here. Resilience for work, household and various everyday functions is promoted and trained without pressure to perform. Depending on individual needs, lifting loads, working above head height or in a forward-leaning trunk posture is trained.

CONCLUSION FOR PRACTICE

- In addition to a purely somatically oriented training concept, chronic pain patients can learn about and positively influence their self-efficacy and sense of coherence through gently guided body awareness exercises and body consciousness. This can also lead to a fear-free movement and real training of the remaining necessary everyday and body functions.

- Physical training in the context of sports therapy requires a high degree of motivation to overcome misconceptions and fears. So a real combination of cognitive body behavior therapy and sports therapy seems to make sense.

- An intensive training with guidance for further self-training on the basis of also playful activation and increase of self-efficacy shows the best long-term results [16].

- Mindful body-oriented movement exercises such as yoga, Feldenkrais, Qi-Gong and the like should be offered by psychologists and sports therapists as a supplement, in parallel with goal-oriented reconditioning training adapted to the patients’ limited capacity.

Literature list at the publisher

Dipl. Sports Sci. and dipl. Physiotherapist André Pirlet