Excessive workload, pressure to economize, predisposing personality traits – physicians are affected by burnout twice as often as the general population. A brief overview of current findings – and tips on how to avoid the burnout trap.

About half of Swiss hospital physicians work an average of 56 hours per week – six hours more than allowed by law. This is the result of the representative DemoSCOPE study conducted in 2017 on behalf of the Association of Swiss Assistant and Senior Physicians (VSAO). Overwork manifests itself as fatigue in every second person, and every third person feels exhausted. Almost 40% reach the limits of their resilience [1]. If this becomes a permanent condition, the step to burnout is not far away. Although burnout syndrome is not an ICD-10 diagnosis, it is considered an occupational stress disorder that can precede or be associated with mental and psychosomatic illnesses. Burnout is measured using the Maslach Burnout Inventory (MBI), a set of questions that examines the dimensions of emotional exhaustion, depersonalization, and reduced performance [2]. For affected physicians, the axes of emotional exhaustion and depersonalization or dullness towards patients are particularly relevant [3].

Burnout among physicians – some figures

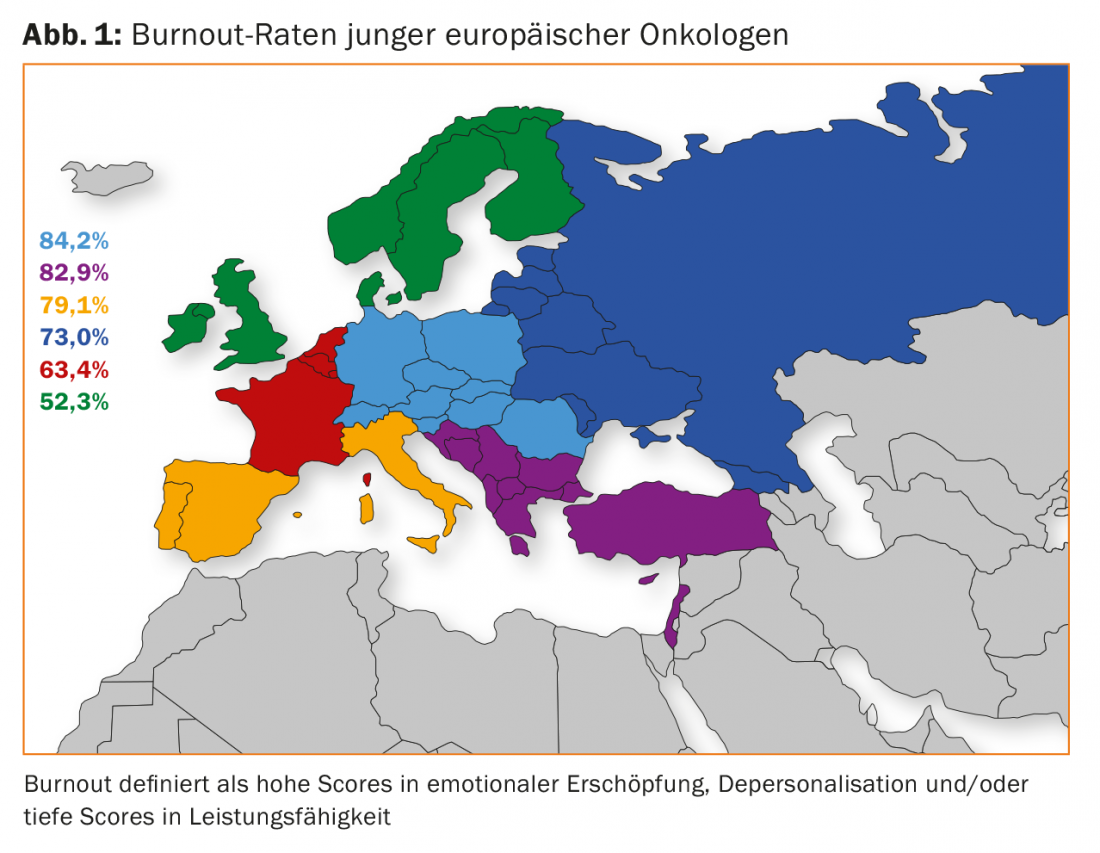

Numerous studies show that burnout is a serious threat, especially for physicians. A study by the Mayo Clinic, for example, concluded that the work-life balance of U.S. physicians deteriorated significantly between 2011 and 2014: More than half of the respondents (n=6880) suffer from burnout syndrome. This means that the burnout rate among physicians is twice as high as in the general population [4]. The trend is also increasing in Switzerland [5]. However, there are differences with regard to the individual areas of expertise. Oncologists are the most affected, with a prevalence of 71% [6]. Country-specific burnout rates are high in Switzerland, among other countries (Fig. 1). Emergency physicians, primary care physicians and general internists [4,7] as well as medical professionals in psychiatric institutions are more at risk [8]. Gender-specific differences are also evident: women tend to become ill more frequently, which is attributed to the double burden of family and professional life, gender aspects within the hierarchy, and a different perception of symptoms [9]. The transition from study to work is considered a critical phase [10].

Etiological factors

Since the opening of the health care system to the market economy, physicians have been confronted with additional external stressors. The workload is further increased by the increased administration effort, for the participants of the DemoSCOPE study the main cause of their overload. There is less and less time for patient contacts. And although digitization has led to increased efficiency in many areas, it sometimes also represents a burden [11]. As a result of economization, physicians are caught between the fronts of their medical aid mission and a market-driven administrative culture. Their room for maneuver is increasingly restricted by cost constraints. This is also accompanied by a loss of status, which has a negative impact on the desire for recognition: The “gods in white” have become cost drivers in the public perception [12]. In addition to these factors, classic stressors in the workplace (e.g. poor work-life balance, lack of support in the event of excessive workload, conflicts, etc.) continue to play an important role. In the hierarchically structured hospital setting, residents in particular run the risk of ending up in a situation where the balance between commitment and reward is no longer guaranteed [13].

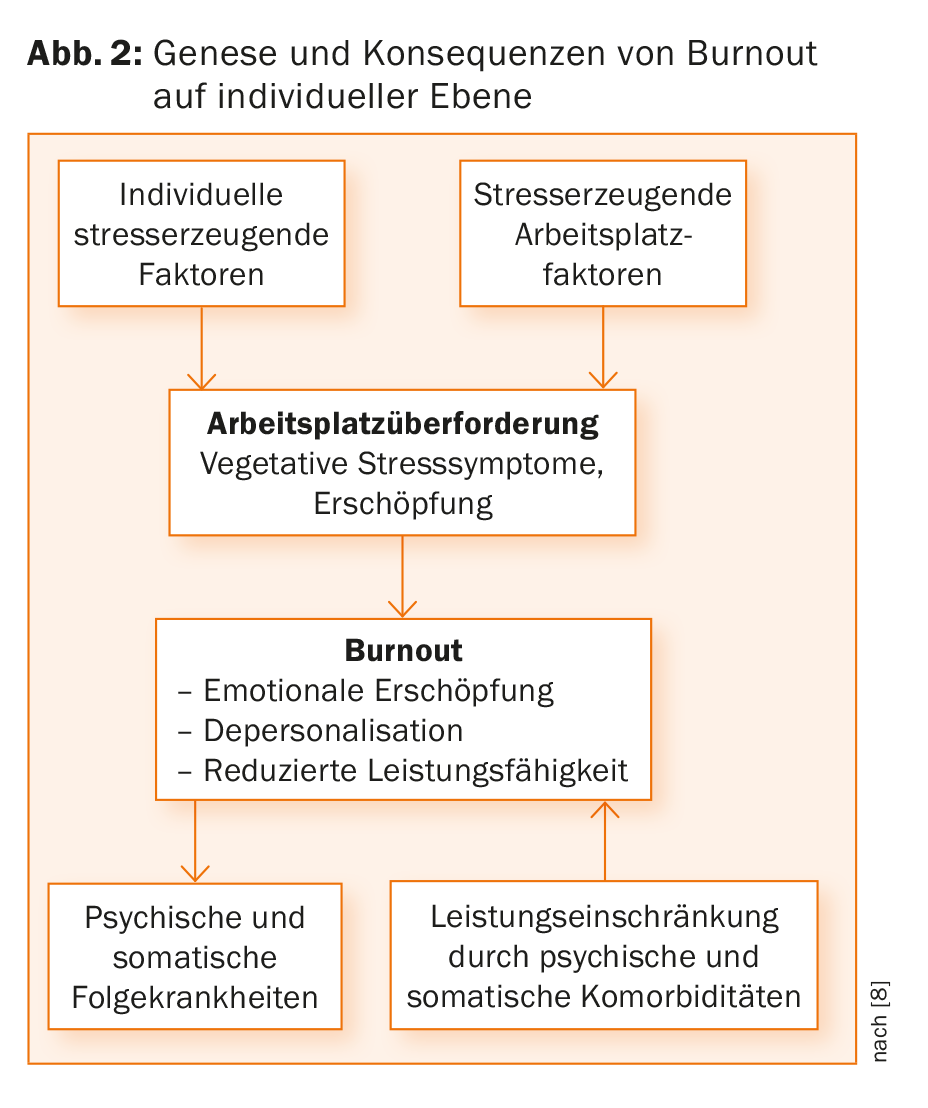

Biographical imprints play an essential role in the development of a burnout syndrome. They control the perception of stress and corresponding stress management strategies. Emotional imbalance is often rooted in childhood: violations of children’s basic needs (e.g. attachment, recognition, orientation, security) can result in excessive controlling behavior, perfectionism or altruism, even self-sacrifice. In the day-to-day work of a physician, these patterns can be destructive. Especially the work with emergencies or chronically ill patients requires constant control by the physician, who wants to fulfill his (possibly individually excessive) responsibility for the patient. The risk of burnout is intensified by a search for recognition linked to self-esteem, which manifests itself in hyperactivity and self-sacrifice. The overactivity in turn prevents a confrontation with the fatal conditioning – until the performance limit is exceeded [13] (Fig.2).

When the doctor becomes the patient

If a physician suffers from burnout, this is not only associated with a general health impairment, but also with a significantly increased risk of suicide and substance abuse [14–16]. Affected physicians also suffer significantly more traffic accidents [17]. Patients are also affected: The quality of treatment decreases, the error rate increases by more than half [1]. For the healthcare system, this means, apart from reduced physician productivity and costs due to medical errors, a brain drain with corresponding financial and supply-related implications: Around one third of all participants in a German study are considering emigration due to the workload [18].

What helps?

As a multidimensional problem, burnout demands integral solutions. A combination of structural changes in working conditions and individual coping strategies is most effective [19]. On an individual level, resilience training has proven to be a useful tool. Resilience is the ability to handle stressful situations in a self-caring manner. Mindfulness can help to notice body signals and develop coping strategies [20]. Anyone who wants to test whether he or she is at risk can do so, among other things, online via the Burnout Risk Test [21]. In addition, support networks such as ReMed exist. The organization, which is funded by the FMH, has specifically targeted physicians since its implementation in 2010. On the one hand, it serves as a platform for the exchange of knowledge and experience regarding health promotion and prevention, and on the other hand, as a confidential point of contact in crisis situations. In 2017, the number of counseling requests was 141, about half of them due to professional overload. Although the internal awareness level of ReMed is currently still at 55%, physicians attribute a high relevance to the network [22]. Hopefully, these and other offerings will gain popularity to help de-taboo the issue of physician burnout.”

Literature:

- VSAO, DemoSCOPE: Workload of residents and senior physicians. Member Survey 2017. www2.vsao.ch/fileupload/20175561028_pdf.pdf, accessed 07/23/18.

- Maslach C, Jackson SE, Leiter MP: Maslach burnout inventory: manual. Mountain View, CA: Consulting Psychologists Press 2009.

- West CP, et al: Single item measures of emotional exhaustion and depersonalization are useful for assessing burnout in medical professionals. J Gen Intern Med 2009; 24: 1318-1321.

- Shanafelt TD, et al: Changes in Burnout and Satisfaction With Work-Life Balance in Physicians and the General US Working Population Between 2011 and 2014. Mayo Clin Proc 2015; 90: 1600-1613.

- Arigoni F, Bovier PA, Sappino AP: Trend in burnout among Swiss doctors. Swiss Med Wkly 2010; 140: w13070.

- Banerjee S, et al: Professional burnout in European young oncologists: results of the European Society for Medical Oncology (ESMO) Young Oncologists Committee Burnout Survey. Ann Oncol 2017; 28: 1590-1596.

- Goehring C, et al: Psychosocial and professional characteristics of burnout in Swiss primary care practitioners: a cross-sectional survey. Swiss Med Wkly 2005; 135: 101-108.

- O’Connor K, Müller Neff D, Pitman S: Burnout in mental health professionals: A systematic review and meta-analysis of prevalence and determinants. Eur Psychiatry 2018; 53: 74-99 [Epub ahead of print].

- Beschoner P, et al: Gender aspects in female and male physicians. Professional life and psychosocial stress. Bundesgesundheitsbl 2016; 59: 1343-1350.

- Dyrbye LN, et al: Physician satisfaction and burnout at different career stages. Mayo Clin Proc 2013; 88: 1358-1367.

- Shanafelt TD, et al: Relationship between clerical buren and characteristics of the electronic environment with physician burnout and professional satisfaction. Mayo Clinic Proc 2016; 91: 836-848.

- Von Känel R: Burnout and resilience in physicians. Prim Hosp Care 2017; 17: 51-56.

- Egle UT: Physician burnout. Journal of Medical Ethics 2015; 61: 13-21.

- Fond G, et al.: Psychiatry: A discipline at specific risk of mental health issues and addictive behavior? Results from the national BOURBON study. J Affect Disord 2018; 238: 534-538.

- Brown SD, Goske MJ, Johnson CM: Beyond substance abuse: stress, burnout, and depression as causes of physician impairment and disruptive behavior. J Am Coll Radiol 2009; 6: 479-485.

- Shanafelt TD, et al: Special report: suicidal ideation among American surgeons. Arch Surg 2011; 146: 45-62.

- West CP, Tan AD, Shanafelt TD: Association of resident fatigue and distress with occupational blood and body fluid exposures and motor vehicle incidents. Mayo Clin Proc 2012; 87: 1138-1144.

- Pantenburg B, et al: Physician emigration from Germany: insights from a survey in Saxony, Germany. BMC Health Serv Res 2018; 18: 341.

- West CP, et al: Interventions to prevent and reduce physician burnout: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet 2016; 388: 2272-2281.

- Bergner T: Burnout prevention. Prevent exhaustion – build energy. Self-help in 12 steps, 3rd edition. Stuttgart: Schattauer, 2015.

- Burnout Risk Test (BRT): www.burnoutprotector.com. As of 07/26/2018.

- ReMed: Support Network for Physicians (PPT). www.fmh.ch/rem/remed/services.html. Accessed 07/23/18.

InFo NEUROLOGY & PSYCHIATRY 2018; 16(6): 38-40.